David LaRocca1, Katie Lohmiller2, Ashley Brooks-Russell1, Katherine A. James3, Scott Harpin4, Jeff Frykholm5, Megan Bartlett6, and Jini Puma1

1 Department of Community and Behavioral Health, Colorado School of Public Health

2 Educational Access Group

3 Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, Colorado School of Public Health

4 College of Nursing, University of Colorado

5 Regis University, Denver, Colorado

6 The Center for Healing and Justice through Sport

Citation:

LaRocca, D., Lohmiller, K., Brooks-Russell, A., James, K.A., Harpin, S., Frykholm, J., Bartlett, M. & Puma, J. (2025). A Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Trauma-informed Sport Training for Youth Sports Coaches. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Trauma-informed care has shown promise as an intervention for preventing and mitigating the negative effects of childhood adversity. This study evaluated the impact of a trauma-informed sport training on youth sports coaches’ attitudes related to trauma-informed care and how their experiences with a trauma-informed sport training explain their attitudes. Utilizing an explanatory sequential mixed methods design, the 35-item Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC-35) was used to measure coaches’ attitudes towards trauma-informed care before and after a 90-minute trauma-informed sport training (n=16), and interviews with participants were conducted between 1-2 months after the training to further explain the quantitative data (n=10). Quantitative results demonstrated significant improvements in coaches’ attitudes related to trauma-informed care and satisfaction with the training’s delivery, content, fit, and value. Themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis of interviews included that the intervention: provided a new perspective on youth behavior; demonstrated the importance of trusting relationships and safe environments; offered complimentary approaches to current coaching practices; raised awareness about coaches’ stress and its impacts; and increased knowledge of brain science and regulation. These study findings provide preliminary evidence supporting the impact of a trauma-informed sport training on coaches’ attitudes.

INTRODUCTION

Childhood adversity includes experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction as well as stressors such as bullying, community violence, racism, and discrimination (Center for Youth Wellness, 2013; Felitti et al., 1998; Karatekin & Hill, 2019). A large body of evidence indicates that exposure to adversity during childhood is linked to negative short-term and long-term health outcomes, and as adversity accumulates, the negative effect on health increases (Bellis et al., 2019; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015; Petruccelli et al., 2019). In childhood, adversity is associated with school absenteeism, violence perpetration, poor mental health outcomes, and emotional, learning, and behavioral disorders (Blodgett & Lanigan, 2018; Burke et al., 2011; Noel-London et al., 2021; Stempel et al., 2017). In adulthood, childhood adversity is associated with the adoption of risky behaviors, including smoking, alcoholism, and substance use, and an increased likelihood of depression, suicidality, obesity, heart disease, lung disease, cancer, and early death (Felitti et al., 1998; Petruccelli et al., 2019).

Strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity can result in toxic stress, or unrelieved activation of the body’s stress response systems (Joos et al., 2019). Toxic stress can disrupt the healthy development of brain architecture and other organ systems and thereby increase the risk for stress-related disease and cognitive impairment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020; Shonkoff & Garner, 2012). Protective factors, however, can mitigate these risks. For example, safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments can protect against toxic stress by assisting an individual in returning to physiological homeostasis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019; Crouch et al., 2019; Mercy, 2009; Schofield et al., 2013). As such, childhood adversity is an important public health issue (Magruder et al., 2017) – the most recent, pre-pandemic data indicates that 33.3% of children in the United States have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) in their lifetime (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2020) – and interventions that leverage protective factors are needed to reduce the significant health impacts of adversity across the life course.

A key intervention used to address adversity is the implementation of trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed care is a framework that provides guidance for programs, organizations, and systems to understand the prevalence of trauma and adversity and their impact on health; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma and adversity; integrate knowledge about trauma and adversity into policies, procedures, and practices; and avoid re-traumatization by approaching people who have experienced trauma and adversity with non-judgmental support (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). SAMHSA further outlines six principles to guide the implementation of trauma-informed care, including safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues (SAMHSA, 2014). The implementation of trauma-informed approaches is not a clinical practice but, rather, a universal strategy that facilitates safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments for all individuals. Successful implementation is an iterative process that requires changes in knowledge, perspectives, attitudes, and skills throughout a program, organization, or system (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2023).

Schools throughout the United States have begun adopting trauma-informed approaches (Thomas et al., 2019), and more than a third of states have implemented trauma-informed approaches at district- or state-wide levels (Maynard et al., 2019). Early research on the impacts of trauma-informed approaches in schools is positive, including improved academic achievement, reduced stress, and behavioral improvements (reduced problem behaviors, detentions, and suspensions) for students (Dorado et al., 2016; Herrenkohl et al., 2019; Oehlberg, 2008). Additionally, a mixed methods research study of trauma-informed practices also reported increases in resilience for students who had experienced multiple forms of adversities (Longhi, 2015; Longhi et al., 2019). Notably, schools implementing trauma-informed approaches have reported positive outcomes among teachers, including improvements in teacher satisfaction and retention (Chang, 2013; Crosby, 2015). In addition to schools, other youth-serving organizations, including pediatric clinics, early childhood education and care centers, and after-school programs (Center for Youth Wellness, 2013; Longhi et al., 2019; Maynard et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2023), have also adopted trauma-informed approaches. While the implementation of trauma-informed approaches in these organizations can, in part, begin to address the effects of adversity and toxic stress, other environments (e.g., community centers; arts, sports, and recreation programs; and faith-based organizations) that reach youth should be considered in the context of implementing and evaluating trauma-informed services.

The youth sports environment is a noteworthy setting for expansion. Based on the most recent data, 53.8% of youth aged 6-17 years in the United States participated in a sports team or took sports lessons after school or on weekends in the last 12 months (The Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2022). Additionally, as part of the Healthy People 2030 goals, the United States Department of Health and Human Services set a sports participation target of 63.3% of children and adolescents (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019, 2023). Based on the current participation rate and the commitment to increasing sports participation, sports are a practical setting to reach a large portion of the youth population and apply trauma-informed approaches to reduce the effects of adversity and toxic stress and subsequently improve health outcomes throughout the lifespan.

When structured appropriately, the sport environment can have a positive impact on youth development (Whitley et al., 2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics states that organized sport participation can be an important component of adolescent physical, psychological, and social health, and participation in sports, particularly team sports, can contribute to positive self-esteem, social identity, and protection against suicide (Logan et al., 2019). Conversely, sport also has a history of marginalization, exclusion, and discrimination, especially for participants identifying as an ethnic minority; lesbian, gay, or bisexual; or disabled (United States Center for SafeSport, 2020; Vertommen et al., 2016). In the United States, youth sports has faced declining participation (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019) due to factors such as privatization, professionalization, and overspecialization (Aspen Institute: Project Play, 2023). These factors have disproportionately excluded youth from lower socioeconomic status and youth with lower levels of fitness from sports participation (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019).

Appropriately structured sport experiences have also been an effective means for supporting youth with complex trauma, reducing trauma symptoms, and promoting emotional regulation and skill-building (Bergholz et al., 2016; D’Andrea et al., 2013; Massey & Williams, 2020). A meta-study reviewing qualitative research on the sports experiences of individuals with a history of trauma reported that carefully planned sports experiences can promote emotional regulation, wellbeing, and posttraumatic growth (Massey & Williams, 2020). Similarly, an evaluation of the “Do the Good” program demonstrated that the integration of trauma-informed care principles into a sports-based intervention can improve behavior and mental health in severely traumatized youth (D’Andrea et al., 2013). Subsequent studies have begun to build evidence for strategies that integrate trauma-informed care into coaching methods and sports programming design (Bergholz et al., 2016) and also into the development and implementation of youth sports organizations and systems that serve diverse populations (Hussey et al., 2023; Shaikh et al., 2021).

Youth sports coaches are integral factors in sport experiences that prevent trauma from occurring, limit retraumatization, and reduce and negate the adverse effects of existing trauma (Bergholz et al., 2016; Folco, 2023; Johnson et al., 2020; Shaikh et al., 2021). For example, safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with adults, such as coaches, is a well-established protective factor that can prevent and mitigate the negative short- and long-term effects of adversity (CDC, 2019; Crouch et al., 2019; Perry, 2009, 2020). However, at present, limited studies exist that use a psychometrically valid instrument to evaluate the impact of trauma-informed interventions on coaches. In its framework and implementation guidance for trauma-informed care, SAMHSA recommends the measurement of staff attitudes towards trauma-informed care in order to “gauge readiness, evaluate the impact of staff training, and assess the sustainability of trauma-informed culture change efforts” (SAMHSA, 2023, p. 32). As such, the purpose of this study was to examine the impact of a trauma-informed sport training on youth sports coaches’ attitudes related to trauma-informed care and how their experiences with a trauma-informed sport training explain their attitudes. An explanatory sequential mixed methods design was employed to address two research questions: What effect does participation in a 90-minute, trauma-informed sport training have on youth sports coaches’ attitudes related to trauma-informed care? And how do youth sports coaches’ experiences with a trauma-informed sport training explain their attitudes related to trauma-informed care?

Methods

Study Design

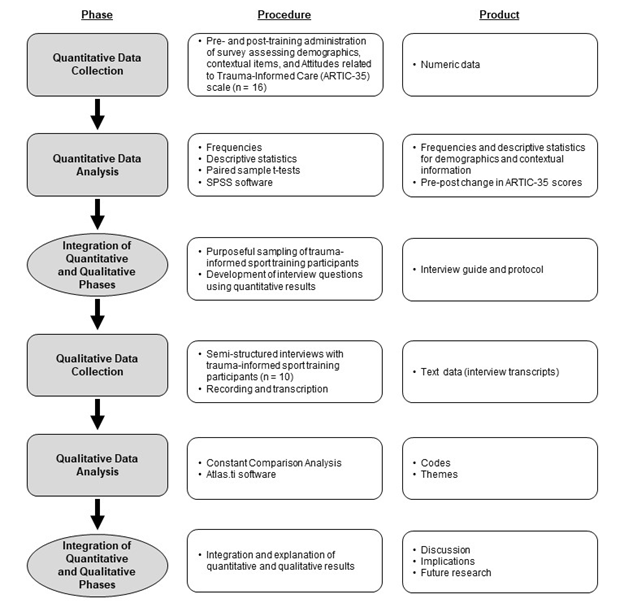

This evaluation was conducted as a mixed methods pilot study within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stage Model of behavioral intervention development (Onken et al., 2014). Per the NIH Stage Model, a pilot study (or Stage I study) focuses on the preliminary testing of a new behavioral intervention or the modification, adaption, or refinement of an existing intervention (in this case, the adaptation of a trauma-informed intervention to the youth sports setting). If a Stage I study produces positive data and outcomes, the intervention is considered appropriate for further testing (e.g., Stage II-V studies that assess efficacy, effectiveness, implementation, and dissemination). Mixed methods designs have also been effectively used to evaluate trauma-informed interventions (Baker et al., 2018; Damian et al., 2019), and this evaluation employed an explanatory sequential mixed methods design (Figure 1) (Gallo & Lee, 2016; McCrudden et al., 2021). In this design, quantitative data examining pre-post changes in attitudes related to trauma-informed approaches and perceived experiences of a trauma-informed sport training were first collected from participants of a trauma-informed sport training. The quantitative data were then analyzed and used to inform the design of an interview guide, which was used to collect qualitative data from the same participants. The qualitative data were then analyzed to complement and explain the quantitative data. This study design and subsequent protocols were reviewed and approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (Protocol #22-0298) and granted a Category 1 exemption for normal educational practice.

Figure 1 – Explanatory sequential mixed methods design with associated procedures and products for each phase

Research Context

Youth sports coaches were recruited from a large soccer club in Colorado that serves a county with a majority white population (76.2%) and 11.8% of residents in poverty (United States Census Bureau, 2024). Programming is provided to youth ages 5-19 and offers experiences ranging from recreational to competitive. The club manages approximately 125 coaches, of which 60% are volunteers and 40% are paid, including both part-time and full-time positions (J. Frykholm, personal communication, June 15, 2023). Among the paid coaches, the interquartile age range is 26-36 years and more than 75% have obtained a bachelor’s degree (J. Frykholm, personal communication, June 15, 2023).

Intervention

This study was conducted in partnership with the Center for Healing and Justice through Sport (CHJS), which utilizes sports participation to support healing, build resilience, and address issues of systemic injustice. Since its inception, CHJS has offered trainings in trauma-informed sport through a partnership with the Neurosequential Network, which employs the Neurosequential Model. The Neurosequential Model is a developmentally-informed, biologically-respectful approach to working with youth, and the model incorporates the science of brain development and processing and the stress response system to help adults understand youth development, behavior, and health (Perry, 2009, 2020). Additionally, it has been used to design trauma-informed approaches for clinical staff and classroom teachers that have improved social-emotional development in young people (Barfield et al., 2011) and improved educators’ attitudes, knowledge, and perceptions of trauma-informed approaches and students’ behavior and academic performance (Lohmiller et al., 2022).

This study implemented CHJS’s 90-minute introduction to trauma-informed approaches in sport, which is intended for audiences with no prior experience in trauma-informed work. Trauma-informed sport is a strategy for preventing trauma caused by sport (e.g., abuse) and other life situations, reducing retraumatization through sport, and reducing and negating the adverse effects of existing trauma through positive relationships, skill building, and promoting regulation. Drawing on concepts from the Neurosequential Model, the CHJS training introduces a model for understanding the brain’s developmental hierarchy (e.g., the brainstem manages automatic functions of the body, such as breathing and heart rate, while the cortex manages complex functions, such as rational thinking and creativity) (Center for Healing and Justice through Sport [CHJS], 2023; Perry, 2009, 2020). The training then uses the model to teach participants how stress influences the brain and subsequent behavior. Key concepts from the training include state dependent functioning, which describes the flock, freeze, flight, and fight continuum with associated mental states of alert, alarm, fear, and terror, and differential state reactivity, which describes different reactions to stress along a continuum of sensitized to resilient (CHJS, 2023; Perry, 2009, 2020). CHJS has extensive experience in sports-based youth development, and based on that expertise, the training then shares specific and practical examples, tools, and strategies that layer these concepts onto existing sport structures, such as practice plans.

For this study, the research team partnered with club administrators to offer four opportunities to participate in the CHJS 90-minute trauma-informed sport training, renamed as “Brain-Based Coaching” per the club’s directives. Three of the training opportunities were offered virtually via an online video conferencing platform, and one training opportunity was offered in person at the club’s headquarters. The opportunities were communicated to club coaches via email and social media, and participation was optional. Youth sports coaches who participated in the trauma-informed training were provided with a brief (postcard) consent form for the quantitative study before the intervention. The form included the purpose of the research, criteria for participation, confidentiality measures, and incentive details (a $50 gift card for completing the pre-survey, training, and post-survey). Coaches who completed the quantitative study were then eligible for the qualitative study; these coaches were again provided with a brief (postcard) consent form for the qualitative study and incentive details (a $20 gift card for participating in an interview). The training was delivered by the lead author, and CHJS provided the lead author with all the materials necessary to deliver the training, including scripts, presentation materials, and handouts. Additionally, CHJS and the lead author met multiple times before the training was delivered to review the script and discuss relevant guidance and advice (e.g., in-person versus online delivery, engagement strategies, and frequently asked questions).

Quantitative Phase

In total, 28 of the eligible 125 club coaches participated in the 90-minute trauma-informed training (participation rate = 22.4%). Among those participants, 16 coaches opted into the quantitative study (study response rate = 57.1%), and demographics and contextual information for these coaches are presented in Table 1. The mean age of coaches was 34.8 (Standard Deviation (SD) = 10.3), and coaches were majority white (93.8%), not Hispanic or Latino (87.5%), and had obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher (81.2%). Regarding coaching characteristics, the mean years spent coaching a primary sport (defined as the “one sport you identify with the most as a coach”) was 11.7 (SD = 9.4). The most highly endorsed reasons for becoming a coach included having played sports as a child (mean = 4.56, SD = 0.73), wanting to stay involved in sport (mean = 4.56, SD = 0.51), and love for teaching sport (mean = 4.56, SD = 0.51) (see Appendix B, Table B1).

Table 1 – Demographics and contextual information of coaches participating in quantitative and qualitative study phases

| Item | Mean (SD) / n (%) | |

| Quantitative Phase (n = 16) | Qualitative Phase (n = 10) | |

| Age in Years (Mean) | 34.8 (10.3) | 37.6 (11.0) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 7 (43.8%) | 6 (60.0%) |

| Male | 9 (56.3%) | 4 (40.0%) |

| Non-binary | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 14 (87.5%) | 9 (90.0%) |

| Race | ||

| African American or Black | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| White | 15 (93.8%) | 9 (90.0%) |

| Education | ||

| Some college | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 8 (50.0%) | 4 (40.0%) |

| Graduate degree | 5 (31.2%) | 4 (40.0%) |

| Primary Sport Coached | ||

| Soccer | 15 (93.8%) | 9 (90.0%) |

| Strength and Conditioning | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| Years Coaching Primary Sport (Mean) | 11.7 (9.4) | 14.3 (10.8) |

| Level of Current Team(s) | ||

| Recreational | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Competitive | 14 (87.5%) | 8 (80.0%) |

The quantitative phase utilized a pretest-posttest survey design and the 35-item Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC-35), a psychometrically valid instrument informed by the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) that measures professionals’ attitudes towards trauma-informed approaches (Baker et al., 2016, 2021). The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that changes in an individual’s attitudes related to specific behaviors can lead to changes in behavioral intention and then behavior (Glanz et al., 2015). Under this theory, coaches’ attitudes towards trauma-informed approaches can directly influence intentions to adopt or engage in trauma-informed approaches. The ARTIC-35 consists of five sub-scales, including underlying causes of problem behaviors and symptoms, responses to problem behavior and symptoms, on-the-job behavior, self-efficacy at work, and reactions to the work. The scale has strong internal consistency reliability (α = 0.91), a strong test-retest reliability correlation (0.82 at less than or equal to 120 days), and construct and criterion-related validity (Baker et al., 2016, 2021). Coaches who consented to participate in the quantitative study completed an online demographic and contextual questionnaire and the ARTIC-35 between one week and one hour prior to participating in the trauma-informed sport training (see Appendix A). After the training, coaches who completed the pre-survey were immediately invited to complete a post-survey, which included the ARTIC-35 and survey items examining the perceived experiences (e.g., satisfaction with delivery, content, fit, and value) of a trauma-informed sport training (see Appendix A), and were contacted up to three times via email over a 2-week period to facilitate completion.

Quantitative analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 29. Frequencies and descriptive statistics were calculated for survey items examining demographics, contextual information, and perceived experiences of the trauma-informed sport training, and paired sample t-tests were used to assess changes in ARTIC-35 scores. Two-tailed p-values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and mean differences, standard deviations, and Cohen’s d were calculated to assess pre-post changes for the overall scale and the five sub-scales.

Qualitative Phase

For the qualitative phase, an interview guide was developed to further assess and explain changes in attitudes related to trauma-informed approaches and the perceived experiences of a trauma-informed sport training (see Appendix A). The interview guide was developed using results from the quantitative analysis as well as input from CHJS staff, including the founder, the director of operations and evaluation, and a lead consultant and trainer. For example, the quantitative data indicated statistically significant increases in pre-post attitudes for the Underlying Causes of Problem Behavior and Symptoms subscale (p = 0.016), which emphasizes behavior that is external and malleable versus internal and fixed. As such, the interview guide included a question that asked, “how, if at all, did the seminar change the way you understand challenging behaviors in your athletes?”, which aimed to elicit the reasoning behind changes in attitudes towards the causes of challenging behaviors in athletes/youth. Interview questions also included “how, if at all, did the seminar change the way you respond to challenging behaviors in your athletes?” and “how, if at all, do you see brain-based coaching fitting in with your goals as a coach?”

Consistent with guidance for designing explanatory sequential mixed method studies, a purposeful sampling approach (Creswell, 2022; Palinkas et al., 2015) was employed to recruit all participants of the trauma-informed sport training who completed both the pre- and post-survey (n = 16). These participants were contacted up to three times via email during the month following the trauma-informed sport training. Participants who consented to participate in the qualitative study then participated in a semi-structured interview of approximately 30-minutes in length using video conferencing software between one and two months after the trauma-informed sport training. Demographics and contextual information for these coaches are presented in Table 1, and this data did not differ significantly from that of coaches who participated in the quantitative phase. The intent of the qualitative data collection and analysis was to explain the quantitative data, and as such, the timeline and duration of this follow-up period was chosen to allow time for the quantitative data to be analyzed, the interview guide to be developed, and interviewees with varying schedules to participate (Creswell, 2022; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts were read multiple times to develop familiarity with the data, and the data were analyzed by the lead author using ATLAS.ti software and a constant comparison analysis approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The data were first coded deductively using constructs from the ARTIC-35 and findings from the quantitative results. Next, an exploratory and inductive analysis was conducted, allowing codes and themes to emerge from the data. In this approach, data were divided into small segments and codes were attached (open coding). Next, codes were grouped into similar categories (axial coding), and then, themes were generated from the categories. A comprehensive audit trail of coding decisions and theme development was maintained throughout the data analysis process, and member checks were conducted with two interviewees (Study Identification (ID) 05 and ID 12) to improve the credibility and trustworthiness of the findings (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Raskind et al., 2019).

RESULTS

Quantitative Results

Pretest-Posttest Survey Results

Paired sample t-tests demonstrated statistically significant differences between pre and post ARTIC-35 scores for the full scale (p < 0.001) and three of the five subscales: Underlying Causes of Problem Behavior and Symptoms (p = 0.016); Responses to Problem Behavior and Symptoms (p < 0.001); and Reactions to the Work (p = 0.023) (Table 2). For these results, the ARTIC-35 scale (Cohen’s d = 1.15) and Responses to Problem Behavior and Symptoms subscale (Cohen’s d = 1.34) demonstrated large effect sizes, and the Underlying Causes of Problem Behavior and Symptoms subscale (Cohen’s d = 0.68) and the Reactions to Work subscale (Cohen’s d = 0.63) demonstrated medium effect sizes (Cohen, 2013; Lakens, 2013).

Table 2 – Pretest to posttest changes in the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC-35) (n = 16)

| Scale | Descriptive Statistics | Paired Sample T-Tests | |||||||||

| Items | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Pre

Mean |

Post

Mean |

Mean Diff. | Sig. | Effect Size | ||

| ARTIC-35: 35-item scale with my five core subscales to be used in setting that have not yet begun implementation of trauma-informed care. | 35 | 4.43 | 6.51 | 5.58 | 0.50 | 5.41 | 5.73 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 1.15** | |

| Underlying Causes of Problem Behavior and Symptoms: Emphasizes behavior that is external and malleable versus internal and fixed | 7 | 4.14 | 6.43 | 5.31 | 0.60 | 5.14 | 5.48 | 0.34 | 0.016 | 0.68* | |

| Responses to Problem Behavior and Symptoms: Emphasizes flexibility, feeling safe, and building healthy relationships versus rules, consequences, and eliminating problem behaviors | 7 | 4.00 | 6.86 | 5.59 | 0.74 | 5.29 | 5.88 | 0.59 | <0.001 | 1.34** | |

| Empathy and Control/On-the-Job Behavior: Endorses empathy-focused behaviors versus control-focused behaviors | 7 | 4.29 | 6.29 | 5.42 | 0.60 | 5.31 | 5.52 | 0.21 | 0.074 | 0.48 | |

| Self-Efficacy at Work: Endorses feeling able to meet the demands of working with a traumatized population versus feeling unable to meet the demands | 7 | 4.14 | 7.00 | 5.84 | 0.74 | 5.78 | 5.91 | 0.13 | 0.471 | 0.19 | |

| Reactions to Work: Endorses appreciating the effects of vicarious traumatization and coping through seeking support versus underappreciating the effects of vicarious traumatization and coping by ignoring | 7 | 4.43 | 7.00 | 5.71 | 0.69 | 5.55 | 5.86 | 0.31 | 0.023 | 0.63* | |

Notes: SD = Standard Deviation; bold = p < 0.05; Effect size measured using Cohen’s d; * = medium effect size; ** = large effect size

Perceived Experiences of a Trauma-Informed Sport Training

Descriptive statistics were generated for post-survey data assessing participants’ experiences of a trauma-informed sport training (Table 3). All participants (100%) agreed or strongly agreed that (1) the information and skills presented in the training were understandable; (2) the information and skills presented in the training will have a positive impact on their coaching; (3) the information and skills presented in the training will have a positive impact on the youth they coach; and (4) they intend to use the information and skills presented in the training in their coaching. Most participants also agreed or strongly agreed that (1) they were satisfied with the amount of information and skills presented in the training (87.5%); (2) the information and skills presented in the training fit with their goals as a youth sports coach (87.5%); and (3) the information and skills presented in the training fit with their current coaching practices (93.8%).

Table 3 – Descriptive statistics for items examining perceived experiences of a trauma-informed sport training (n = 16)

| Item | n | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD |

| Delivery. The information and skills presented in this training were understandable. | 16 | 4 | 5 | 4.81 | 0.40 |

| Content. I am satisfied with the amount of information and skills presented in this training. | 16 | 3 | 5 | 4.50 | 0.73 |

| Fit. The information and skills presented in this training fit with my goals as a youth sports coach. | 16 | 3 | 5 | 4.63 | 0.72 |

| Value. The information and skills presented in this training will have a positive impact on my coaching. | 16 | 3 | 5 | 4.50 | 0.63 |

| Value. The information and skills presented in this training will have a positive impact on the youth that I coach. | 16 | 4 | 5 | 4.81 | 0.40 |

| Fit. The information and skills presented in this training fit with my current coaching practices. | 16 | 4 | 5 | 4.63 | 0.50 |

| Intent/Demand. I intend to use the information and skills presented in this training in my coaching. | 16 | 4 | 5 | 4.81 | 0.40 |

Notes: Response options and scoring included: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree; SD = Standard Deviation.

Qualitative Results

Themes resulting from the deductive and inductive constant comparison analyses included that the training provided a new perspective on youth behavior; demonstrated the importance of trusting relationships and safe environments; offered complimentary approaches to current coaching practices; raised awareness about coaches’ stress and its impacts; and increased knowledge of brain science and regulation. These themes are described below in detail with supporting quotes and associated study IDs, gender identity, and coaching level.

A New Perspective on Youth Behavior

Interviewees consistently reported that the training expanded their perspective on youth behavior and what may be causing certain behaviors, with a specific focus on stressful events from the day (e.g., “a rough day at school” [ID 03, male, competitive]) and, more broadly, life (e.g., “their family life” [ID 04, female, recreational] and “we don’t know what the stress is that these kids are under” [ID 15, female, competitive]). For example, one participant stated “in the past, I might have thought, oh, that kid is just difficult or something, and not really acknowledged they have stuff going on. There’s a reason that they are acting out like this” (ID 14, female, recreational). Participants also noted that the training encouraged them to “look for things that might not be typical” (ID 04, female, recreational) and “to be curious to ask questions about why they [youth] might be behaving the way they’re behaving” (ID 06, female, competitive). Codes that contributed to the development of this theme included ‘underlying causes of problem behavior and symptoms’ and ‘experiences of stress’.

Trusting Relationships and Safe Environments

Interviewees emphasized the importance of psychologically safe environments and trusting and supportive relationships in brain-based (i.e., trauma-informed) sport. Responses described how stress can impact athletes’ behavior and the role of a coach in recognizing the connection and tailoring the environment. For example, one participant stated:

Brain-based [trauma-informed] coaching to me is taking into account the place that the players are coming from in those moments and being able to recognize it. And then how can I adjust my training to help them, whether it’s giving them a break? Or maybe they do need that push? Or maybe it’s the rhythmic passing? (ID 06, female, competitive)

Similarly, another participant described how recognizing stress and building trust are integral components of trauma-informed sport, stating:

Trust allows you then to see, recognize, and understand the players. Be on the lookout for deviations in their typical behaviors and know what sort of stresses and anxieties that might be, and then create an environment that mitigates against that. (ID 05, male, competitive)

Multiple participants also emphasized safe environments (e.g., “the right environment has to be safe” [ID 03, male, competitive]) and team cultures that normalize mistakes (e.g., “mistakes are okay, we let it [practice] be a safe space” [ID 12, female, competitive] and “we’re trying really hard here to have an immediate positive response, so mistake rituals is one thing” [ID 05, male, competitive]) and thereby reduce stress produced by sports participation itself. Codes that contributed to the development of this theme included ‘responses to problem behavior and symptoms,’ ‘safety’, and ‘trust’.

Complementary Approaches to Coaching Practices

Interviewees reported that the information and strategies presented in the training were complementary and undisruptive to their current coaching practices. One participant stated “I see them [information and strategies from the training] fitting in very well, because it was all very practical. Everything that was in the seminar is stuff that, you know, someone could literally go apply” (ID 14, female, recreational), and another went further in reporting “it fits in really well and it kind of helps me regulate my own stress” (ID 12, female, competitive). Interviewees also indicated that the training validated certain coaching practices that are already being implemented (e.g., “it validated what we currently do” [ID 08, male, competitive]). Codes that contributed to the development of this theme included ‘fit with individual goals and culture’ and ‘validated coaching practices’.

Stress Awareness

Interviewees reported that the training facilitated an awareness of personal stress from coaching. Interviewees described examples of coaching related stressors (e.g., planning for practices and games and managing parents) and the impact of stress on their own behaviors. One participant stated:

I get that for myself, personally, when I’m just dysregulated. And I know what that feels like. I’m late and behind. I’m anxious. I’m just worried about how things are going to come across. And I feel that during training sessions. You know, there’s days when I’m regulated and throw anything at me and I’m on it. There are other days, I’m dysregulated for whatever reasons, and every time someone else comes in, I’m worried about it, is this good enough? So, the dysregulated idea really resonates with me. (ID 05, male, competitive)

For another participant, the training facilitated an awareness of stress as well as potential coping strategies to manage stress: “I’m not going to do the girls any help if I’m the one freaking out on the sideline. So just realizing like, okay, I’m getting too stressed, I’m going to go get a drink of my water” (ID 12, female, competitive). Codes that contributed to the development of this theme included ‘coaching stress’ and ‘reactions to the work’.

Tolerable Stress and Regulation

Participants were also asked about the retention of information and strategies from the training, including information related to the Neurosequential Model and strategies for warm-ups and cool-downs, transitions, play, and regulating interventions. Participants frequently described the concept of tolerable stress and the related strategies of mistake rituals and scaffolding, two specific trauma-informed sport strategies from the training. For example, scaffolding refers to the practice of adding challenge in small doses and then pulling back the challenge after pushing athletes beyond the comfort zone to facilitate regulation (CHJS, 2023). Accordingly, one participant described scaffolding techniques as:

How you can elevate the stress and then decrease it, instead of just making it more stressful the entire time, and then letting them relax, and then the repetitive movement. So having them do the same rondos [a soccer-specific exercise] every single day before they get there, or just getting something that can kind of decrease the stress before we start. (ID 12, female, competitive)

Participants also focused on the concepts of regulation and dysregulation. One participant discussed being aware of an athlete’s state, stating:

What can we do to recognize the state of regulation that players come in with? First to recognize it, then secondly, what can we do to make sure that we bring it [stress] back down to baseline, which would be super important in terms of their emotional regulation. (ID 04, female, recreational)

Trauma-informed sport strategies related to regulation and dysregulation were also emphasized, with a focus on “patterned, repetitive, and rhythmic activity” (ID 05, male, competitive) and how such activity can help “when players get stressed” (ID 07, female, competitive). Per the training, patterned, repetitive, and rhythmic activities help individuals regulate and can be as simple as passing a soccer ball back and forth with a partner (CHJS, 2023). One coach described the utility of regulating interventions, noting that a key concept that they adopted from the training was:

The idea of that [patterned, repetitive, and rhythmic activity] being a really good sort of reset and bring somebody back down to a baseline level where they can be more receptive to whatever we’re trying to work on or whatever we’re trying to achieve that day. (ID 04, female, recreational)

Codes that contributed to the development of this theme included ‘brain science’, ‘regulating interventions,’ and ‘good stress’.

DISCUSSION

The 90-minute trauma-informed sport training produced statistically significant increases in positive attitudes related to trauma-informed care for participating coaches, as assessed by the ARTIC-35, and the integration of quantitative and qualitative data (see Appendix B, Table B2) demonstrated that participants perceived the training to have satisfactory delivery, content, fit, and value. To the authors’ knowledge, this study was the first to implement trauma-informed care training in a youth sports context while evaluating its impact on coaches’ attitudes related to trauma-informed care. Notably, the effect size of pre-post changes was large for the ARTIC-35 (Cohen’s d = 1.14) and similar to previously reported effect sizes for trauma-informed training for school educators (Cohen’s d = 1.34), including teachers, behavioral health professionals, and principals, using a pre-post design and the ARTIC-35 (Parker et al., 2020). Per SAMHSA’s framework and implementation guidance on trauma-informed care, the favorability of staff attitudes related to trauma-informed care is integral to ensuring readiness for, effectiveness of, and sustainability of trauma-informed care across a variety of settings and systems (Baker et al., 2021; SAMHSA, 2014, 2023).

These results suggest that participating coaches may be more willing and ready to implement trauma-informed approaches, but notably, whether coaches enact such behavior change is dependent upon numerous factors. One interviewee, for example, described implementation challenges for trauma-informed sport practices, such as getting “bogged down in the details” (ID 04, female, recreational) of coordinating and managing practices and games. This challenge may detract from the implementation of trauma-informed approaches and reduce a coach’s ability to focus on the needs of participants. As such, organizational policy and support may be necessary to relieve coaches from certain coordination work, remove other implementation challenges, and empower them to implement trauma-informed approaches (SAMHSA, 2014, 2023).

This mixed methods study demonstrated that the use of a model to explain properties and functions of the brain was integral in changing attitudes related to trauma-informed approaches in sport. The training employed content from the Neurosequential Model, which teaches concepts such as the brain’s developmental hierarchy, state dependent functioning, and differential state reactivity (Perry, 2009, 2020). These concepts first provided a foundation for understanding how stress can be an underlying cause of challenging behavior (e.g., “the seminar really keyed me in to saying, what are kids bringing from school, from their family life?” [ID 04, female, recreational]). Second, the concepts demonstrated the utility of trauma-informed approaches, such as how safe relationships and environments can mitigate the impacts of stress on the brain and behavior (e.g., “the right environment has to be safe” [ID 03, male, competitive] and “building trust with the proper boundaries and the understanding of what we’re here to do” [ID 14, female, recreational]). These attitudes also extended to personal awareness of stress for participants, some of whom appreciated the effects of stress on their own behaviors and ability to support youth (e.g., “a dysregulated adult is not going to be as helpful with dysregulated players, and I feel the pressure in this environment too” [ID 05, male, competitive]).

Trauma-informed approaches are a non-clinical, best practice for supporting the well-being of all youth, especially those impacted by adversity, and based on this pilot study, youth sports are a promising environment for the expansion of trauma-informed approaches. More broadly, youth sports also warrant further investigation as an environment for supporting youth mental health and well-being. Evidence at the systems-level has demonstrated how the integration of mental health systems within sporting contexts can address mental health problems among adolescents (Dowell et al., 2021), and at the interpersonal level, coaches can fulfill the crucial role of safe, stable, and nurturing adults for youth sports participants. Importantly, a recent study reported that coaches perceive their role to be inclusive of mental health, including promotion, encouraging help seeking behaviors, and parental notification of concerns, and emphasized the need for coaching education on mental health literacy through face-to-face sessions with practical components and online content availability (Ferguson et al., 2019). Moreover, from the youth perspective, adolescents have reported a need for clubs, parents, and coaches to develop knowledge around mental health and youth-focused strategies for providing mental health support through sports (Swann et al., 2018). Ultimately, mental health supports in youth program contexts, such as sports, may be critically important in promoting recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, which contributed to high rates of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents (Loades et al., 2020; Marques de Miranda et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2021).

Despite this evidence, sports-based mental health and well-being interventions are an untapped strategy for supporting healthy youth development (Camiré et al., 2014). Based on results from the National Coach Survey, only 14% of the approximately six million coaches in the United States felt prepared to work with youth who had experienced adversity or trauma in their home environment (Anderson-Butcher & Bates, 2022). Furthermore, the survey reported great interest in trauma-informed care training: 57% of coaches had never participated in a trauma-informed care training, and 60% of coaches wanted more training on the topic (Anderson-Butcher & Bates, 2022). Recent data also indicates that only 32.5% of coaches are trained in positive youth development techniques, which complement trauma-informed approaches and focus on the strengths of youth and their potential to thrive when given the right supports (e.g., safe environments and positive and caring relationships) (The Aspen Institute: Project Play, 2020). Ultimately, the demand from coaches to be trained in trauma-informed care is significant, and the promising results of the current study suggest that sport programs, organizations, and systems can improve coaches’ knowledge of and attitudes towards trauma-informed care through participation in a brief trauma-informed sport training, such as the CHJS training examined in this study.

This pilot study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the pretest-posttest design that was employed did not include a control group, and, as a result, the increases in positive attitudes related to trauma-informed approaches in participants could have been caused by factors other than the trauma-informed sport training. Notably, per the NIH Stage Model, Stage I studies (like this study) involve pilot testing a behavioral intervention and are intended to assess feasibility and contribute to an understanding of behavior change mechanisms, not test efficacy and effectiveness. Second, 28 of 125 coaches managed by the club chose to participate in the trauma-informed sport training (including 16 participants who consented to the quantitative study and 10 participants who consented to the qualitative study). While these participants were similar in age, education level, and demographics to the entire population of coaches at the club, they also self-selected to participate in a trauma-informed sport training. Participating coaching may have been more interested in brain science, trauma, and stress or participating in professional development related to coaching and thereby could have been fundamentally different than coaches who chose not to participate. Importantly, participants in the study also received monetary incentives, which can increase selection bias. Finally, the range in times between training and interview participation (minimum = 1 month, maximum = 2 months) may have influenced each participant’s ability to recall information and strategies during the qualitative phase. Ultimately, despite the small sample size, the results from this study align with past studies that support sport as a context for preventing trauma, reducing retraumatization, and reducing and negating the adverse effects of existing trauma (Bergholz et al., 2016; Massey & Williams, 2020; Shaikh et al., 2021; Whitley et al., 2018).

While this study has the potential to guide future research and practice related to trauma-informed approaches in the youth sports environment, overall, more robust and interdisciplinary research is needed to understand the effectiveness of trauma-informed approaches in all settings (Maynard et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2019). In the sports context, future research should more rigorously examine the coach- and participant-level impacts of trauma-informed sport trainings and study contexts (e.g., team versus individual sport and recreational versus competitive sport) that may influence implementation. More broadly, sport should be further examined to identify and better understand conditions that promote (e.g., safe, stable, and nurturing relationships; social connectedness; and regular physical activity) and damage (e.g., unhealthy power dynamics and pressures to perform) mental health and wellbeing (Zarrett & Veliz, 2023).

Conclusion

One in three children report exposure to adversity (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2020), and disruptions in daily life and isolation from the COVID-19 pandemic, a collective trauma, have contributed to historically high rates of stress, anxiety, and depression in adolescents (Loades et al., 2020; Marques de Miranda et al., 2020). Sports – the most popular extracurricular activity in the United States – represent a unique opportunity to address the growing concerns related to trauma, toxic stress, and mental health by leveraging foundational components of the experience that improve physical and mental health, such as physical activity (Biddle et al., 2019), and enhancing interpersonal components that facilitate healthy relationships and social connectedness. This pilot study provides preliminary evidence that training in trauma-informed sport increases youth sports coaches’ positive attitudes related to trauma-informed approaches and is perceived to have satisfactory delivery, content, fit, and value. The novel training, which has not traditionally been offered as part of coaching education, increased coaches’ understanding of the impacts of trauma, signs and symptoms of trauma, and practical strategies for creating safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments that can mitigate the effects of trauma. Results from this pilot study warrant further investigation into the efficacy and effectiveness of trauma-informed sport trainings, specifically those that are grounded in a brain-based model and offer practical and adaptable strategies, and represent a promising strategy for leveraging sport to improve population mental health and well-being.

APPENDICES

Click here to download appendices in PDF format.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this report to disclose.

FUNDING

None

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was made possible by a partnership with the Center for Healing and Justice through Sport.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Anderson-Butcher, D., & Bates, S. (2022). National Coach Survey Final Report. The Ohio State University, LIFEsports Initiative. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/national-coach-survey-report-preliminary-analysis.pdf

Aspen Institute: Project Play. (2023). Youth sports playbook: Ask kids what they want. Project Play. https://projectplay.org/youth-sports/playbook/ask-kids-what-they-want

Baker, C. N., Brown, S. M., Overstreet, S., Wilcox, P. D., & New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2021). Validation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care Scale (ARTIC). Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(5), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000989

Baker, C. N., Brown, S. M., Wilcox, P. D., Overstreet, S., & Arora, P. (2016). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale. School Mental Health, 8(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9161-0

Baker, C. N., Brown, S. M., Wilcox, P., Verlenden, J. M., Black, C. L., & Grant, B.-J. E. (2018). The implementation and effect of trauma-informed care within residential youth services in rural Canada: A mixed methods case study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(6), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000327

Barfield, S., Dobson, C., Gaskill, R., & Perry, B. (2011). Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics in a therapeutic preschool: Implications for work with children with complex neuropsychiatric problems. International Journal of Play Therapy, 21(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025955

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Ramos Rodriguez, G., Sethi, D., & Passmore, J. (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(10), e517–e528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8

Bergholz, L., Stafford, E., & D’Andrea, W. (2016). Creating trauma-informed sports programming for traumatized youth: Core principles for an adjunctive therapeutic approach. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2016.1211836

Biddle, S. J. H., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G., & Vergeer, I. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011

Blodgett, C., & Lanigan, J. D. (2018). The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(1), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000256

Burke, N. J., Hellman, J. L., Scott, B. G., Weems, C. F., & Carrion, V. G. (2011). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(6), 408–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006

Camiré, M., Trudel, P., & Forneris, T. (2014). Examining how model youth sport coaches learn to facilitate positive youth development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 19(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2012.726975

Center for Healing & Justice Through Sport. (2023). Nothing heals like sport: A new playbook for coaches. https://chjs.org/resources/read-nothing-heals-like-sport-a-new-playbook-for-coaches/

Center for Youth Wellness. (2013). An unhealthy dose of stress. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RD50llP2dimEdV3zn0eGrgtCi2TWfakH/view

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) prevention resource for action: A compilation of the best available evidence (p. 35). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ACEs-Prevention-Resource_508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Chang, M-L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: Appraisal, regulation and coping. Motivation and Emotion, 37(4), 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9335-0

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Creswell, J. (2022). A concise introduction to mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications, Ltd.

Creswell, J., & Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. (4th ed.). Sage Publications, Ltd.

Crosby, S. D. (2015). An ecological perspective on emerging trauma-informed teaching practices. Children & Schools, 37(4), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv027

Crouch, E., Radcliff, E., Strompolis, M., & Srivastav, A. (2019). Safe, stable, and nurtured: Protective factors against poor physical and mental health outcomes following exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0217-9

Damian, A. J., Mendelson, T., Bowie, J., & Gallo, J. J. (2019). A mixed methods exploratory assessment of the usefulness of Baltimore City Health Department’s trauma-informed care training intervention. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(2), 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000357

D’Andrea, W., Bergholz, L., Fortunato, A., & Spinazzola, J. (2013). Play to the whistle: A pilot investigation of a sports-based intervention for traumatized girls in residential treatment. Journal of Family Violence, 28(7), 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9533-x

Dorado, J., Martinez, M., McArthur, L., & Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. School Mental Health, 8(1), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0

Dowell, T. L., Waters, A. M., Usher, W., Farrell, L. J., Donovan, C. L., Modecki, K. L., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Castle, M., & Hinchey, J. (2021). Tackling mental health in youth sporting programs: A pilot study of a holistic program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00984-9

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Ferguson, H. L., Swann, C., Liddle, S. K., & Vella, S. A. (2019). Investigating youth sports coaches’ perceptions of their role in adolescent mental health. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1466839

Folco, M. (2023). The neurobiological impact of trauma on youth development: Restoring relationships and regulation through sport. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00937-w

Gallo, J., & Lee, S. (2016). Mixed methods in behavioral intervention research. In L.N Gitlin & S.J. Czaja (Eds.), Behavioral Intervention Research: Designing, Evaluating and Implementing (pp. 195–211). Springer Publishing Company.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Viswanath, K. (2015). Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Health Resources and Services Administration. (2020). Adverse Childhood Experiences: NSCH Data Brief (The National Survey of Children’s Health). https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/data-research/nsch-ace-databrief.pdf

Herrenkohl, T. I., Hong, S., & Verbrugge, B. (2019). Trauma‐informed programs based in schools: Linking concepts to practices and assessing the evidence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12362

Hussey, K., Blom, L., Huysmans, Z., Voelker, D., Moore, M., & Mulvihill, T. (2023). Trauma-informed youth sport: Identifying program characteristics and challenges to advance practice. Journal of Youth Development, 18(3). https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/jyd/vol18/iss3/4

Johnson, N., Hanna, K., Novak, J., & Giardino, A. P. (2020). U.S. Center for SafeSport: Preventing Abuse in Sports. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 28(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2019-0049

Joos, C. M., McDonald, A., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2019). Extending the toxic stress model into adolescence: Profiles of cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 107, 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.002

Kalmakis, K. A., & Chandler, G. E. (2015). Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(8), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12215

Karatekin, C., & Hill, M. (2019). Expanding the original definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(3), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-018-0237-5

Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1218-1239.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Logan, K., Cuff, S., LaBella, C., Brooks, A., Canty, G., Diamond, A., Hennrikus, W., Moffatt, K., Nemeth, B., Pengel, B., Peterson, A., & Stricker, P. (2019). Organized sports for children, preadolescents, and adolescents. Pediatrics, 143(6), e20190997. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0997

Lohmiller, K., Gruber, H., Harpin, S., Belansky, E. S., James, K. A., Pfeiffer, J. P., & Leiferman, J. (2022). The S.I.T.E. Framework: A novel approach for sustainably integrating trauma-informed approaches in schools. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(4), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00461-6

Longhi, D. (2015). Higher resilience and school performance among students with disproportionately high adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) at Lincoln High, in Walla Walla, Washington, 2009 to 2013 (p. 27). https://www.pacesconnection.com/g/aces-in-education/fileSendAction/fcType/0/fcOid/476303634598273268/filePointer/476303634600806432/fodoid/476303634600806428/Lincoln%20School%20Report%20March%202015%20Paper%20Tigers.pdf

Longhi, D., Brown, M., Barila, T., Reed, S. F., & Porter, L. (2019). How to increase community-wide resilience and decrease inequalities due to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Strategies from Walla Walla, Washington. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2019.1633071

Magruder, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., & Elmore Borbon, D. L. (2017). Trauma is a public health issue. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1375338. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1375338

Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva Athanasio, B., Sena Oliveira, A. C., & Simoes-e-Silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

Massey, W. V., & Williams, T. L. (2020). Sporting activities for individuals who experienced trauma during their youth: A meta-study. Qualitative Health Research, 30(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319849563

Maynard, B. R., Farina, A., Dell, N. A., & Kelly, M. S. (2019). Effects of trauma‐informed approaches in schools: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15(1–2). https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1018

McCrudden, M. T., Marchand, G., & Schutz, P. A. (2021). Joint displays for mixed methods research in psychology. Methods in Psychology, 5, 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2021.100067

Mercy, J. A. (2009). Creating a healthier future through early interventions for children. JAMA, 301(21), 2262. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.803

Noel-London, K., Ortiz, K., & BeLue, R. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) & youth sports participation: Does a gradient exist? Child Abuse & Neglect, 113, 104924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104924

Oehlberg, B. (2008). Why schools need to be trauma-informed. Trauma and Loss: Research and Interventions, 8(2), 4. http://www.traumainformedcareproject.org/resources/WhySchoolsNeedToBeTraumaInformed(2).pdf

Onken, L. S., Carroll, K. M., Shoham, V., Cuthbert, B. N., & Riddle, M. (2014). Reenvisioning clinical science: Unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613497932

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Parker, J., Olson, S., & Bunde, J. (2020). The impact of trauma-based training on educators. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 13(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00261-5

Perry, B. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(4), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903004350

Perry, B. (2020). The Neurosequential Model: A developmentally sensitive, neuroscience-informed approach to clinical problem solving. In J. Mitchell, J. Tucci, & E. Tronick (Eds.), The Handbook of Therapeutic Child Care for Children (pp. 137–155). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Petruccelli, K., Davis, J., & Berman, T. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

Raskind, I. G., Shelton, R. C., Comeau, D. L., Cooper, H. L. F., Griffith, D. M., & Kegler, M. C. (2019). A review of qualitative data analysis practices in health education and health behavior research. Health Education & Behavior, 46(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198118795019

Schmidt, S. J., Barblan, L. P., Lory, I., & Landolt, M. A. (2021). Age-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1901407. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1901407

Schofield, T. J., Lee, R. D., & Merrick, M. T. (2013). Safe, stable, nurturing relationships as a moderator of intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), S32–S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.004

Shaikh, M., Bean, C., Bergholz, L., Rojas, M., Ali, M., & Forneris, T. (2021). Integrating a sport-based trauma-sensitive program in a national youth-serving organization. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 38(4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00776-7

Shonkoff, J. P., & Garner, A. S. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Stempel, H., Cox-Martin, M., Bronsert, M., Dickinson, L. M., & Allison, M. A. (2017). Chronic school absenteeism and the role of adverse childhood experiences. Academic Pediatrics, 17(8), 837–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.013

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Ltd.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884; p. 27). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma14-4884.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023). Practical Guide for Implementing a Trauma-Informed Approach (SAMHSA Publication No. PEP23-06-05-005). National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep23-06-05-005.pdf

Sun, Y., Blewitt, C., Minson, V., Bajayo, R., Cameron, L., & Skouteris, H. (2023). Trauma-informed interventions in early childhood education and care settings: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1), 648-662. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231162967

Swann, C., Telenta, J., Draper, G., Liddle, S., Fogarty, A., Hurley, D., & Vella, S. (2018). Youth sport as a context for supporting mental health: Adolescent male perspectives. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.11.008

The Aspen Institute: Project Play. (2020). Youth sports facts. https://www.aspenprojectplay.org/youth-sports-facts/challenges

The Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2022). National survey of children’s health (2016-present). https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey

Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., & Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-Informed Practices in Schools Across Two Decades: An Interdisciplinary Review of Research. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 422–452. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18821123

United States Census Bureau. (2024). Quick Facts: Boulder County, Colorado. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/bouldercountycolorado

United States Center for SafeSport. (2020). 2020 athlete culture & climate survey. https://uscenterforsafesport.org/survey-results/

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). The national youth sports strategy (p. 112). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-10/National_Youth_Sports_Strategy.pdf

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Increase the proportion of children and adolescents who play sports. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/physical-activity/increase-proportion-children-and-adolescents-who-play-sports-pa-12

Vertommen, T., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N., Wouters, K., Kampen, J. K., Brackenridge, C. H., Rhind, D. J. A., Neels, K., & Van Den Eede, F. (2016). Interpersonal violence against children in sport in the Netherlands and Belgium. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.006

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., Camiré, M., Boutet, M., & Borbee, A. (2019). Sport-based youth development interventions in the United States: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(89). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6387-z

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., & Wilkison, M. (2018). A systems theory of development through sport for traumatized and disadvantaged youth. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.004

Zarrett, N., & Veliz, P. T. (2023). The healing power of sport: COVID-19 and girls’ participation, health, and achievement. Women’s Sports Foundation. https://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/The-Healing-Power-of-Sport-FINAL.pdf