Jack Nelson1, Anne-Marie Jackson1, Chanel Phillips1, Danny Poa1, and Te Kahurangi Skelton1

1 University of Otago, New Zealand

Citation:

Nelson, J., Jackson, A., Phillips, C., Poa, D., & Skelton, T.K. (2023). Te Papa Tākaro o te Tuakiri: The Field of Identity in Indigenous Māori Rugby. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

KŌRERO WHAKARĀPŌPOTO: ABSTRACT

This paper describes findings from an Indigenous student’s postgraduate research alongside an Indigenous rugby organisation, Otago Māori Rugby. The aim of this research was to explore how Otago Māori Rugby incorporated Māori values to enhance Māori identity and welRlbeing. This research utilised Kaupapa Māori Theory and methodology (Smith, 2015). Five semi-structured interviews were completed with members of Otago Māori rugby on topics related to Māori identity and wellbeing. Deductive and inductive analysis was used. The main findings are presented in “Te Papa Tākaro o te Tuakiri: The Field of Identity”. The two primary deductive themes were the application of: taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle) with the subthemes of whakapapa (genealogy), identity, Te Reo Māori (Māori language) and tikanga (custom); and whānau (extended family structure) with the subthemes of whanaungatanga (relationship building) and community involvement. The four primary inductive themes that emerged were: (a) whakaurunga (engagement); (b) tangata whenuatanga (people of the land); (c) influence of cultural values for mainstream; and (d) safe avenue for rangatahi (youth). The findings will contribute towards understanding the importance of Māori cultural values, identity, and wellbeing within Indigenous sport.

TE PAPA TĀKARO O TE TUAKIRI: THE FIELD OF IDENTITY IN INDIGENOUS MĀORI RUGBY

Māui1 was born premature; his mother threw him into the sea wrapped in a tress of hair from her topknot. The waves of Tangaroa (god of the ocean) supported Māui ensuring he survived. His grandfather Tama-nui-ki-te-Rangi then found him on the beach, covered by swarms of flies and gulls, it was at this moment Tama-nui-ki-te-Rangi decided to nourish Māui to adolescence. Tama-nui-ki-te-Rangi raised him, teaching Māui his whakapapa (genealogy) and tribal traditions, so he could stand strong and proud as an adult.

This pūrākau (cultural narrative) tells the narrative of one of the great Polynesian demigods Māui. Pūrākau are located within Māori worldview and contain whakapapa and mātauranga (Māori knowledge and practice) which provide anchors for cultural identity and wellbeing. This pūrākau is significant for the first author as it was an opportunity to see himself within his own cultural identity. The first author is a child of whāngai (Māori adoption practice), but his upbringing was largely disconnected to his taha Māori (Māori side). This pūrākau is one of the first expressions of tamaiti whāngai (adopted child). The pūrākau conceptualises the values within the process of whāngai and the importance of identity. During the first author’s upbringing, he sought out team sports as a coping mechanism to gain a sense of belonging and identity due to this cultural disconnection. From a personal perspective of whāngai and reconnection to Māori culture, team sports had created an avenue where cultural aspects could be taught. Two years ago, the lead author became a volunteer trainer, coach and Board member of Otago Māori Rugby for the rangatahi (youth) men’s team. Through this experience, he saw how Indigenous sports teams, such as Otago Māori Rugby, could be an opportunity to enhance Indigenous cultural identity and wellbeing. This then led into his graduate research which forms the basis of this paper.

Aotearoa (New Zealand) has a proud history of Indigenous Māori rugby (Mulholland, 2009). Part of that proud history is Otago Māori Rugby. Otago Māori Rugby is a regional Māori sport organisation based in the southern part of Te Waipounamu, Aotearoa (South Island of New Zealand). Otago Māori Rugby is affiliated to the Te Waipounamu Māori Rugby Board (South Island Māori Rugby Board), and to the New Zealand Māori Rugby Board. Otago Māori Rugby also has a close association with its mainstream counterpart Otago Rugby Football Union. Otago Māori Rugby is a small group of volunteers attempting to inspire whānau (family), hapū (subtribe) and iwi (tribe) through rugby. Māori players, coaches, managers, trainers, volunteers and whānau from the Otago region are encouraged to participate in Māori rugby, cultural activities and āhurei (rugby festivals and tournaments).

Otago Māori Rugby is a vehicle for the transmission of Indigenous knowledge and practice through a sport that is popular for Māori in Aotearoa. To provide context for this paper, we will describe Otago Māori Rugby in more detail. In 2022, there were 1256 registered Māori rugby players in the Otago region across all ages and grades, with approximately 70 coaches. The activities centre on recruiting, selecting, training and then playing at the Te Waipounamu Ahurei where teams from across Te Waipounamu come together in a tournament. All practices, games and Board meetings are led with tikanga or specific Otago Māori Rugby protocols which are embedded from the ancestral landscapes of Ngāi Tahu (the traditional landowners of Otago). These protocols include karakia (prayers), paki mahi (relationship building energisers for unification), pepeha (cultural introductions) and the normalisation of our Indigenous language Te Reo Māori for example. It is very normal to have intergenerational whānau (family) members present at all activities from young children through to our Indigenous elders. Kai (food) is an important part of our cultural practices, and we will often share in food after practices and certainly games whether hosting or visiting. The games are played with an intent of expression for ngā kare ā-roto (innermost emotions) that is unique to Indigenous peoples, and often very much captures the spirit of Māui (our eponymous ancestor). Māori rugby is a positive vehicle for rangatahi to be rangatahi and to engage in their culture and identity through a sport they love. Rangatahi make friendships for life and are inspired to be themselves. They are exposed to all different people from different walks of life who are there to support them to be the best that they can be. Although not the focus, nor the interest explicitly in this paper, many Indigenous Māori youth are positioned negatively in society and one of our foundational pillars of Otago Māori Rugby is rangatahi ora or flourishing youth wellness and we instead position rangatahi and indeed all Māori and Indigenous peoples as full of limitless potential.

The aim of this research was to explore how Otago Māori Rugby incorporated Māori values to enhance Māori identity and wellbeing. In this paper firstly we explore ngā āhuatanga Māori Māori values and identity focusing on mātauranga Māori, tikanga (protocols) and whakapapa. Secondly, we outline ngā hātepe, the methodology and methods. Namely, we utilised kaupapa Māori theory as the methodological approach. Semi-structured interviews were completed. The transcripts were analysed deductively through the application of kaupapa Māori theory and inductively through examining themes that emerged from the data. Thirdly, we present the data in ngā hua results. The results are then described in whakamārama o ngā hua where we outline the main themes from the analysis with supporting literature.

Ngā Āhuatanga Māori: Māori Values and Identity

Māori values, identity and wellbeing are located within Māori worldview. Māori worldview is the construct that holds the values and principles of how Māori interact within the world (Marsden, 2003). Marsden (2003) explains that we as Māori are derived from atua, the supreme beings, which establishes our connection to the world. Māori worldview inspires our mātauranga, tikanga, and whakapapa (Mead, 2016).

Mātauranga Māori is a knowledge tradition that had its genesis in ancient Polynesia (Sadler, 2007). Tikanga are the protocols in which Māori abide by to live in a respectful manner that preserves the mana (prestige, authority) of the atua and the people around them (Mead, 2016). Whakapapa are the genealogical links that tie us to the atua of this world, it is the layering of ancestor upon ancestor all the way down to your individual line of being (Hudson et al., 2007).

Māori identity includes any person who has Māori ancestry and chooses to identify as Māori. Identifying as Māori suggests having, living, recognising, and acknowledging a whole range of beliefs and practices that vary over time and within the appellation known collectively as Māori (Erueti & Palmer, 2014). Houkamau & Sibley (2010) explain Māori identity as embedded in history, traditions, customs, language, songs, and ceremonies of an individual’s culture. These factors are often positively influenced within Māori communities such as marae (sacred place) and create the foundation of one’s Māori identity. However, in terms of self-identity, the relevance of so-called traditional values is not the same for all Māori, and not all share the same cultural experiences or understandings for language, beliefs, or place of residence (Erueti & Palmer, 2014). Therefore, it is crucial to support and strengthen Māori identity. Some of these concepts are further unpacked in the whakamārama o ngā hua sections where we have incorporated literature within the primary themes and subthemes of this research. In addition, it is important to understand that the needs of individual identity will vary.

Understanding the importance of building culturally safe communities allows others to explore cultures and enhance their individuality. Pitama et al. (2002) believe by utilising the environment concerning communities and whānau will equip youth with the knowledge to strengthen their cultural identity. According to Te Huia (2015) language and culturally safe environments are essential in developing confidence within Māori identity. Engaging in mātauranga will enhance cultural identity and give Māori the ability to self-affiliate based on what they have gained, which helps build a sense of belonging (Pitama, et al., 2002; Te Huia, 2015). These studies indicate how obtaining mātauranga Māori is significant towards identity and connection with culture. In the next section we discuss ngā hātepe methodology and methods that were used in this study.

NGĀ HĀTEPE: METHODS

Kaupapa Māori theory and methodology was used in this research (Smith, 2015). Kaupapa Māori theory and methodology refers to a body of knowledge integral to Māori epistemological and ontological constructions of the world (Hapeta, Palmer & Kuroda, 2019). Smith (1997) highlights six key principles of kaupapa Māori theory and methodology: (a) tino rangatiratanga (the self-determination principle); (b) taonga tuku iho (the cultural aspirations principle); (c) ako Māori (the culturally preferred pedagogy principle); (d) kia piki ake i nga raruraru o te kainga (the socio-economic mediation principle); (e) whānau (the extended family structure principle); and (f) kaupapa (the collective philosophy principle). In this paper, the principles of taonga tuku iho (the cultural aspirations principle) and whānau (the extended family structure principle) were used. Although all the principles are relevant, due to the size and scope of the postgraduate research study, these two principles were selected. Taonga tuku iho (the cultural aspirations principles) aligns closely to identity, and the importance of cultural identity. Whānau (the extended family structure principle) is the basic unit of Māori social structure partly from which stems cultural identity and a guiding focus for the lead author’s own journey to cultural identity.

The primary method utilised was semi structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews are a method of interviewing where the conversation is not directed into a set structure, instead it is free flowing and allows room for adaptation (Hanara, 2020). The interview questions were related to Otago Māori Rugby, cultural principles, cultural identity, and wellbeing. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and opened with their understanding of Otago Māori Rugby and the ability to promote cultural principles and enhance wellbeing.

There were five participants. The participants were three Māori men and two Māori women aged between 20-50years. Participant One is a pakeke (adult) Māori female who is involved in Otago Māori as a volunteer and a mother of a rangatahi player. Participant Two is a pakeke Māori male who is part of Otago Māori Rugby as a father of one of the rangatahi. Participant Three is a pakeke Māori male who was a previous coach, Board member for Otago Māori Rugby. Participant Four is a pakeke Māori female, involved within Otago Māori Rugby as a senior professional player. Participant Five is a pakeke Māori male rugby player for a senior team.

Deductive and inductive analysis was used. The data was examined deductively through applying kaupapa Māori theory, namely taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle) and whānau (extended family structure) (Pihama et al., 2002). Inductive analysis involves themes that emerge from the data and themes that are organically produced (Azungah, 2018). The interviews were transcribed verbatim, and these were read and re-read. The key words, concepts, phrases and quotes were grouped according to either deductive or inductively analysis. Some of the main findings of these analyses are presented in the next section. Due to constraints on word limits we have presented a selection of the findings of the study two tables.

NGĀ HUA: RESULTS

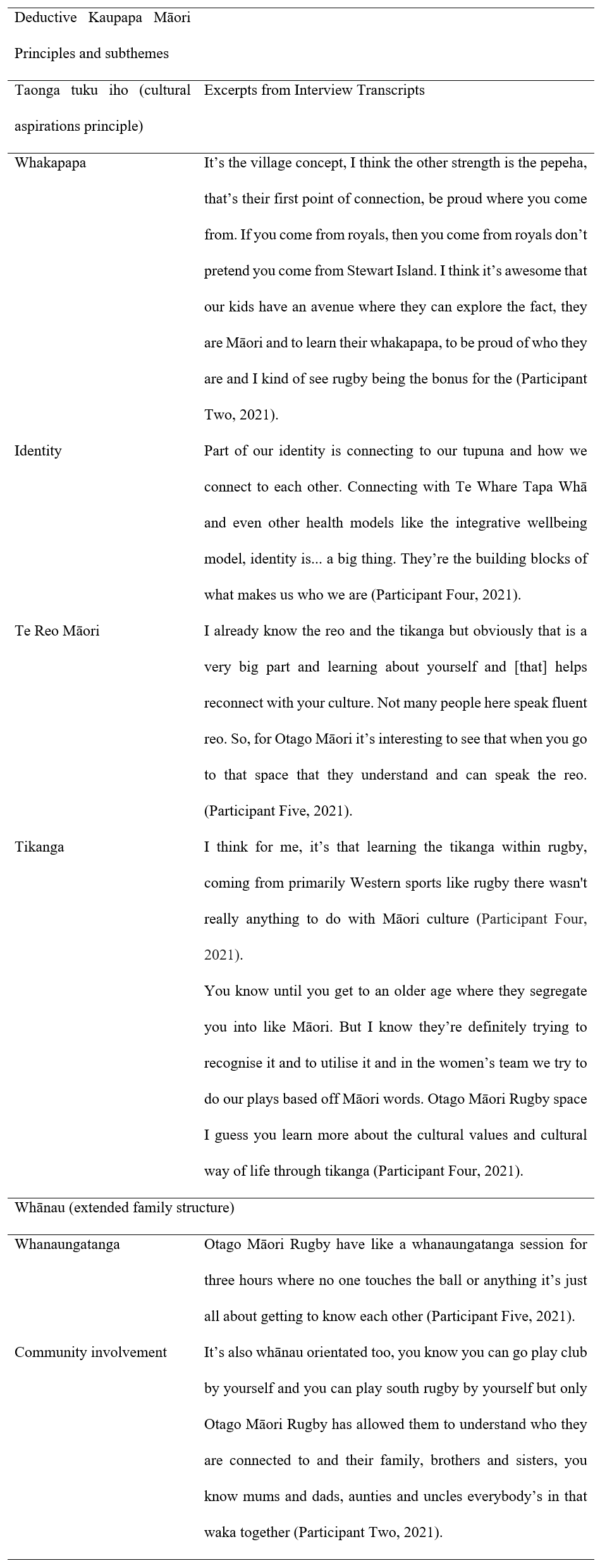

The main results of this study are presented in the figure and two tables below. We discuss these in further detail in the next section.

Figure 1 – Main Findings of Research Te Papa Tākaro o te Tuakiri (top) and The Field of Identity (bottom)

Figure 1 uses the symbolism and shape of a rugby ball to depict a visual representation of the main results identified in the research. The top image reflects the key themes in the Māori language and the bottom image represents their English translations. The outer edges of the rugby ball reflect the deductive themes associated with the principles of taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle) and whānau (extended family structure). These are: whakapapa, identity, Te Reo Māori, tikanga, whanaungatanga and community involvement.

Moving toward the centre, are four main segments which represent the four key emerging themes revealed through inductive analysis: whakaurunga, tangata whenuatanga, cultural values for mainstream sports and safe avenues for rangatahi. This model, Te Papa Tākaro o Tuakiri—The Field of Identity, provides a symbolic image of the main findings of the study as well as emphasises identity as being vital.

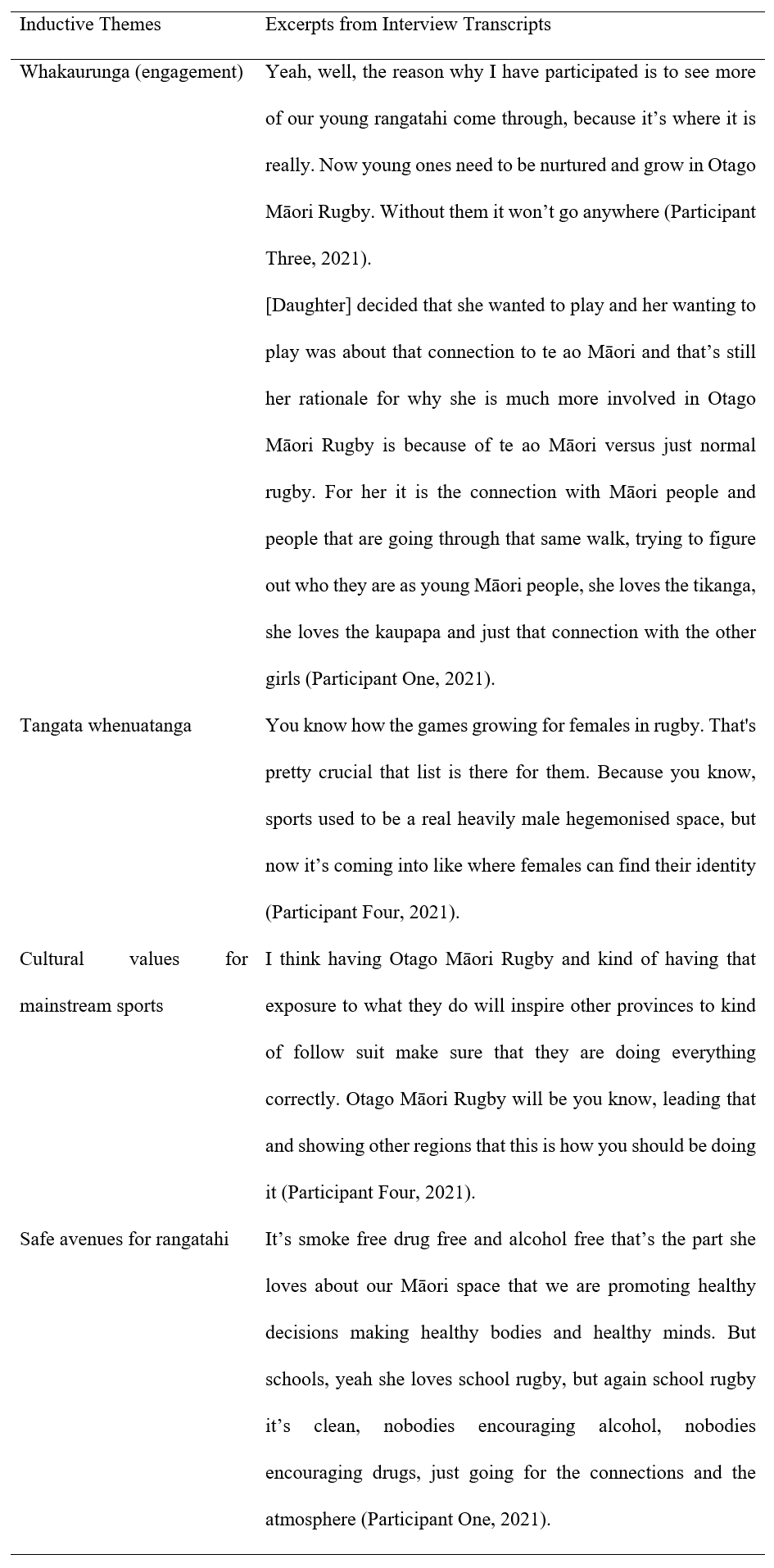

Table 1 – Deductive Kaupapa Māori Principles Themes and Subthemes of Taonga Tuku Iho (Cultural Aspirations Principle) and Whānau (Extended Family Structure) with Accompanying Examples from Participant Interview Transcripts

Table 1 presents a collation of the key excerpts from the participants as they pertain to the deductive themes, or the outer aspect of the Te Papa Tākaro o Tuakiri—The Field of Identity model.

Table 2 – Inductive Themes with Accompanying Examples from Participant Interview Transcripts

Table 2 highlights key excerpts from the participants as they pertain to the inductive themes or the inner segments of the Te Papa Tākaro o Tuakiri—The Field of Identity model. The next section is whakamārama o ngā hua discussion. In accordance with kaupapa Māori theory and methodology and how the findings were presented in the overall study, additional literature is interwoven with the data from the interview participants.

WHAKAMĀRAMA O NGĀ HUA: DISCUSSION

In this section we present the deductive analysis which was the application of taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle) and whānau (the extended family principle). Taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle) had the subthemes of whakapapa, identity, Te Reo Māori and tikanga. Whānau (the extended family principle) had the subthemes of whanaungatanga and community involvement. We also explore the inductive analysis to highlight the emergent themes of whakaurunga, tangata whenuatanga, influences of cultural values for mainstream and safe avenue for rangatahi.

Deductive Analysis: Taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle)

The first kaupapa Māori principle that was applied to the interview data was taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations principle). This principle asserts that cultural aspirations such as whakapapa, identity, Te Reo Māori and tikanga for example, are critical in understanding kaupapa Māori (Pihama et al., 2002; Smith, 2003). There were four subthemes identified: whakapapa, identity, Te Reo Māori and tikanga.

Whakapapa

Whakapapa is a philosophical construct that explains how all things are derived from ancestors (Roberts, 2013). Te Rito (2007) express the importance of whakapapa to form a sense of identity. Moeke-Pickering (1996) claims Māori find whakapapa crucial for how they self-identify and give meaning to life. Whakapapa arises as a theme because it comprises of several beliefs, values and, whakapapa is vital for the development of cultural identity and wellbeing. Three out of five participants specifically signified the importance of whakapapa and the part it plays in Otago Māori Rugby.

For example, as highlighted in Table 1, Participant Two states “I think the other strength is the pepeha, that’s their first point of connection, be proud of where you come from”. This quote highlights the importance of pepeha in relation to whakapapa and identity as Māori. Pepeha is a specific Māori cultural idiom and marker of cultural identity. Often pēpeha will include important landmarks or cultural histories relating to whakapapa and ancestral connections. This supports Moeke-Pickering (1996) who states Māori find whakapapa important for self-identification. Participant Two further explains, “I think it’s awesome that our kids have an avenue where they can explore the fact, they are Māori and to learn their whakapapa, to be proud of who they are and I kind of see rugby being the bonus for them”. It is from this expression the participant was able to identify how Otago Māori Rugby and the community, support rangatahi in understanding their whakapapa. Whakapapa supports the formation of identity.

Identity

Cultural identity is essential for Māori health and wellbeing (Moeke-Pickering, 1996). Te Huia (2015) expresses how identity develops the ability to self-identify as Māori and becomes important towards individual development. Two out of five participants specifically refer to identity. For example, Participant Four stated that “Te Whare Tapa Whā2 and even other health models like the integrative wellbeing model” are created by and for Māori. This framework has been constructed by academic research in relation to identity and wellbeing (Durie, 1982). Only recently has Participant Four reconnected with her culture and understands from a holistic lens the importance of identity as she uses her own personal experience to explain “they’re [Māori health models] the building blocks of what makes us who we are”.

Te Reo

Te Reo Māori is the Māori language. Barr & Seals (2018) state that Te Reo Māori is important to Māori as it represents a symbol of identity and status within New Zealand society. Furthermore, Leoni & Pōtiki (2019) clarify that the Māori language becomes an identity marker for all New Zealanders, whether consciously or not. As a cultural identity marker for all New Zealanders, they argue that there is much work to be undertaken in order to ensure that Te Reo Māori flourishes both within the home and educational settings, including academic settings. Three out of five participants acknowledged Te Reo Māori as an important aspect for Māori. Participant Five believes because he is familiar with Te Reo Māori that he was interested to observe how the coaches and board members of Otago Māori Rugby teach and apply this cultural value. When Participant Five states “not many people here speak fluent reo. So, for Otago Māori it’s interesting to see that when you go to that space that they understand and can speak the reo”, he demonstrates that he understands the significance of Te Reo Māori and sees that it is used effectively within an Otago Māori Rugby setting.

Although Te Reo Māori was mentioned and further discussed in the interviews, it was suggested that all participants through education, mainstream sports and general lifestyle activities struggled to describe their experience of Māori culture outside of Otago Māori Rugby. Given the New Zealand government has a statutory obligation to protect and develop Te Reo Māori under the Māori Language Act 1987, it has been made clear by observations and an inductive analysis that there are limited spaces where Te Reo Māori exists for Māori players. This also suggested that regardless of how direct the questions were in relation to their exposure of Te Reo Māori, the participants are limited to Te Reo Māori and tikanga outside of Otago Māori Rugby.

Tikanga

Tikanga is a framework or body of rules and values used to govern or shape people’s behaviour, or a code of expected behaviour, and is analogous to all Māori values and culture. Harmsworth (2005) states tikanga often refers to the correct way of doing things, including custom, protocols, process, rules, etiquette, formality, codes, condition, ethic, morals, and method. Tikanga is mentioned by three out of five participants as a crucial component within Otago Māori rugby. Participant Four reflects on how Otago Māori rugby makes the conscious effort of implementing tikanga and cultural values.

The quote from Participant Four shows the disparity between the two environments of rugby and Māori rugby when it comes to cultural influence, cultural values, and beliefs. Participant Four first explains that “Western sports like rugby there wasn’t really anything to do with Māori culture,” whereas within a Māori rugby environment “learning the tikanga within rugby” became a part of the team experience. Participant Four then explains further stating that within the “Otago Māori Rugby space I guess you learn more about the cultural values and cultural way of life through tikanga.” These specific sentences resonate with the idea of tikanga as an aspect to consider within Otago Māori Rugby. Because of its limited incorporation within Westernised teams, it’s difficult to fully understand or grasp the importance tikanga has for Māori within rugby and Māori culture. Tikanga is a diverse concept which refers to beliefs associated with practices and procedures that are monitored when dealing with groups or individuals (Mead, 2016). Therefore, considering Participant Four’s perspective and the current literature which indicates the role tikanga has in understanding cultural values within collective spaces or team sports, the implementation of tikanga is vital.

Deductive Analysis: Whānau

The second kaupapa Māori principle that was applied to the interview data was whānau (extended family structure). The whānau principle refers to the extended family. Whānau is the basic unit of Māori social structure and is descended from a common ancestor, within which certain roles and responsibilities are maintained (Durie, 2001). Kaupapa whānau is where people are joined together through a shared purpose or aspiration, such as Otago Māori Rugby, where people may not necessarily be related through a common ancestor, however they share a common purpose. There were two subthemes drawn from the data: whanaungatanga and community involvement.

Whanaungatanga

Whanaungatanga specifically refers to solidifying relationships and strengthening connections. O’Carroll (2013) states whanaungatanga is a Māori practice and the building of relationships through physical spaces. Harmsworth (2005) defined whanaungatanga as bonds of kinship that exist within and between whānau, hapū, and iwi. Whanaungatanga can encourage a safe environment where Māori can express and explore their cultural identity. Three out of five participants specifically discussed whanaungatanga in their interviews.

From Participant Five’s quote we see an example of how Otago Māori Rugby prioritises whanaungatanga within team environments before progressing towards training sessions that aim to improve the physical skills of their players. Participant Five realises during the introduction phase into Otago Māori Rugby, he understands why whanaungatanga is crucial for existing members. Many participants acknowledged that whanaungatanga is essential towards team culture especially Māori.

Community Involvement

Community involvement refers to the local populations of a particular area, as Eriksson & Lindström (2008) articulates how community engagement can demonstrate support, empowerment, enhanced wellbeing, safe physical, and emotional environments. Participant Two recognises how “their family, brothers and sisters, you know mums and dads, aunties and uncles everybody’s in that waka together”. This quote describes how Otago Māori Rugby involves the surrounding community. Being an inclusive and diverse organisation, it was important for Otago Māori Rugby to incorporate community assistance. Otago Māori Rugby tries to include whānau members and players across the entire community to enhance wellbeing through development of cultural identity. Participant Two’s understanding aligns with Pitama et al. (2002) who describe how utilising the environment in relation to communities and whānau will equip youth with the knowledge to strengthen their cultural identity.

Inductive Analysis

There were four inductive themes that emerged from this research as shown in Table 2. These were whakaurunga (engagement), tangata whenuatanga, influences of cultural values for mainstream and safe avenue for rangatahi.

Whakaurunga (engagement)

Whakaurunga is related to the reasons that Māori partake and engage within Otago Māori Rugby. Pitama et al. (2002) suggest that engagement in a wider community is important for identity development. Four out of five participants recognise whakaurunga as an important theme that is embedded within Otago Māori Rugby. As indicated, Participant Three identified the importance of educating rangatahi about cultural values. Based on his statement “the reason why I have participated is to see more of our young rangatahi come through, because it’s where it is really.” Participant Three acknowledges if safe physical and emotional environments are created then more children and youth will feel welcomed within Otago Māori Rugby. Pitama et al. (2002) also believe that by utilising the environment concerning communities and whānau, it will equip youth with the knowledge to strengthen their cultural identity. This particularly resonated with Participant Three as he states “now young ones need to be nurtured and grow in Otago Māori Rugby, without them it won’t go anywhere” which is his personal reasoning for participating in this space.

Participant One explains the significance of having culturally safe environments which reflects her daughter’s involvement within Otago Māori Rugby. Participant One’s quote indicates the significance of an Otago Māori Rugby space for her child and further expresses how “for her it is the connection with Māori people and people that are going through that same walk, trying to figure out who they are as young Māori, she loves the tikanga, she loves the kaupapa” which again, signifies the multiple components that are associated within the Otago Māori Rugby space.

Tangata Whenuatanga

Tangata whenua are the Indigenous people or people born of the land. Māori are the Indigenous people within this research context. Tangata whenuatanga represents the “place based, socio-cultural awareness and knowledge” (Ministry of Education, 2011, p. 3) of the whenua we come from. The Ministry of Education (2011) explains that tangata whenuatanga is about “affirming Māori learners as Māori. Providing contexts for learning where the language, identity and culture (cultural locatedness) of Māori learners and their whānau is affirmed” (p. 4).

Participant Four acknowledges the benefits of becoming an Otago Māori Rugby member, she identifies the cultural aspirations that are upheld in this organisation that aren’t replicated in professional and recreational female rugby teams. Participant Four mentions “You know how the games growing for females in rugby,” she appreciates the space within Otago Māori Rugby where she can develop both her gender and cultural identities. Again, this links back to the previous discussion of the importance of supporting both sporting and cultural aspirations of players and management.

Another example of this theme is evident with Participant Four who is constantly challenged with her identity. She describes how Otago Māori Rugby utilises rugby and te ao Māori (Māori worldview) to construct cultural identity for both male and female rugby players. Participant Four states “because you know, sports used to be a real heavily male hegemonised space, but now it’s coming into like where females can find their identity” reflects how Otago Māori Rugby is gender diverse and targets tangata whenuatanga as a whole, which includes both female and male athletes.

Influence of cultural values for mainstream. Māori culture derives from traditional knowledge and values which then determines how an individual chooses to operate within society. Together cultural values are intended for Māori to affirm their place in Aotearoa as tangata whenua. The Ministry of Education (2011) expresses how obtaining cultural values is vital for Māori learners to uphold the integrity, sincerity, and respect towards Māori beliefs. In addition to this, Hapeta et al. (2015) explains that the number of Māori athletes involved in rugby has increased. Exposure of cultural values needs to be embedded within mainstream sports to enhance cultural identity for Māori players. Three out of five Participants acknowledge the influence cultural values have within sports that develops cultural identity. Participant Five understands the intentions of Otago Māori and can envision a future application where cultural values within sports becomes normalised. This quote by Participant Four identifies a lack of Māori cultural application outside of Otago Māori Rugby but agreed that this can be rectified by implementing cultural values through education and mainstream sport settings.

Safe Avenue for Rangatahi

Creating environments where rangatahi can engage in traditional knowledge safely is significant for growth in cultural engagement and therefore cultural identity. Pitama, et al. (2002) indicate the importance of child protection which refers to the child’s upbringing and their exposure that evolves around whānau, hapū, and iwi. Furthermore, Eriksson & Lindström (2008) also express how community engagement can demonstrate support, empowerment, enhanced wellbeing, safe physical, and emotional environments. Otago Māori Rugby is an avenue where rangatahi can engage in traditional knowledge and physical activity.

Participant One has a strong sense that both schools and Otago Māori Rugby offer safe environments “It’s smoke free drug free and alcohol free that’s the part she loves about our Māori space” she also indicates “nobody’s encouraging alcohol, nobody’s encouraging drugs in school either”. These comments describe a parent’s need for culturally and physically safe spaces for their children. She extends her thoughts by positively acknowledging how “we [Otago Māori Rugby] are promoting healthy decisions making healthy bodies and healthy minds”. These are factors that are important for whānau to know when their children are in the care of others.

KŌRERO WHAKAMUTUNGA: CONCLUSION

This paper described how Otago Māori Rugby incorporated Māori values to enhance Māori identity and wellbeing within their organisation. The various themes that emerged from the participant interviews, demonstrated what is most important to Otago Māori Rugby. Taonga tuku iho encompassed core Māori concepts of whakapapa, the importance of language, Māori tikanga and identity. These four themes reflect the meaning of taonga tuku iho, because these values are the treasures passed down to us by our ancestors. In this sense, Otago Māori Rugby are continuing this transmission of knowledge, by passing down these taonga to our future Māori athletes, so that their identity and wellbeing flourishes alongside their sporting abilities.

In addition, Otago Māori Rugby espoused the notion of whānau and importance of people and relationships. This was evident through the whanaungatanga that took precedence in the organisation and the clear intention for community involvement by providing an inclusive and welcoming space for community input. When family members and the wider community can feel part of the organisation, it then becomes one large family, all concerned with looking after the wellbeing and health of their athletes/whānau members. The remaining themes of whakaurunga, tangata whenuatanga, cultural values in mainstream, and safe avenue, ultimately showcased how important Māori cultural values are for Indigenous player’s identity and wellbeing in the sport.

Returning to the Māui pūrākau provided at the beginning of this paper, there are many Māori who, like Māui, struggled with their cultural identity and sense of belonging in their younger ages. As the first author noted, rugby provided him with a point of connection after his initial struggles to learn about taha Māori, and from there his identity and wellbeing blossomed. Otago Māori Rugby are an Indigenous sport organisation with a focus on nurturing wellbeing and strengthening identity of their players alongside the skills of the game, reflecting a sport-plus approach (Hapeta, Stewart-Withers & Palmer, 2019). Indigenous organisations, like Otago Māori Rugby, have a lot to offer in the sport-for-development space, where cultural values, identity, and wellbeing are at the forefront of everything they do.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors are colleagues with Dr Jeremy Hapeta and Dr Audrey Giles.

FUNDING

Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, Te Koronga.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the five participants of this study for sharing their knowledge and experience. A special thank you also to Otago Māori Rugby for their support throughout this research. Associate Professor Anne-Marie Jackson is current Chair of Otago Māori Rugby and the Board fully support this research and paper and we thank Jack Nelson for his tautoko (support) for Otago Māori Rugby. Ngā mihi nui ki a koutou.

NOTES

1 A Māori demigod who is well known throughout Polynesia. From a Māori perspective, he undertook many feats such as slowing the sun, fishing up the North Island, attempting to trick the Goddess of Death Hinenuitepō for example. Māui is often described as our trickster hero, akin to many Indigenous cultures’ trickster hero and heroines.

2 This refers to Tā (Sir) Mason Durie’s model of Māori health where positive health is symbolically referred to as a Māori meeting house. For a person and their whānau (family) to be well, each wall or side of the house must be maintained. The four sides of the house are: te taha wairua (spiritual health); te taha hinengaro (mental health); te taha whānau (family health) and; te taha tinana (physical health).

REFERENCES

Azungah, T. (2018). Qualitative research: Deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal, 18(4), 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-D-18-00035

Barr, S., & Seals, C. A. (2018). He reo for our future: Te Reo Māori and teacher identities, attitudes, and micro-policies in mainstream New Zealand schools. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 17(6), 434-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2018.1505517

Durie M, (1985). A Maori perspective of health. Social Science and Medicine, 20(5), 483-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90363-6

Durie, M. (2001). Mauri Ora: The dynamics of Māori health. Otago University Press.

Eriksson, M., & Lindström, B. (2008). A salutogenic interpretation of the Ottawa Charter. Health Promotion International, 23(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dan014

Erueti, B., & Palmer, F. R. (2014). Te Whariki Tuakiri (the identity mat): Māori elite athletes and the expression of ethno-cultural identity in global sport. Sport in Society, 17(8), 1061-1075. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.838351

Hanara, B. (2020). Tangaroa Wai Noa, Tangaroa Wai Tapu, Tangaroa Wairoro [Master’s thesis, University of Otago]. OUR Archive. http://hdl.handle.net/10523/10188

Hapeta, J., Mulholland, M., & Kuroda, Y. (2015). Tracking the stacking: The All Blacks from 1880–1980 [Paper presented]. World in Union. International Rugby Conference. Brighton, UK.

Hapeta, J., Palmer, F., & Kuroda, Y. (2019). Cultural identity, leadership and well-being: How indigenous storytelling contributed to well-being in a New Zealand provincial rugby team. Public Health, 176, 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.12.010

Hapeta, J., Stewart-Withers, R., & Palmer, F. (2019). Sport for social change with Aotearoa New Zealand youth: Navigating the theory – practice nexus through indigenous principles. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 481-492. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0246

Harmsworth, G. R. (2005). Report on incorporation of traditional values/tikanga into contemporary Māori business organisations and process. Landcare Research. https://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/uploads/public/researchpubs/Harmsworth_report_trad_values_tikanga.pdf

Houkamau, C. A., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). The multi-dimensional model of Māori identity and cultural engagement. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 39(1), 8-28.

Hudson, M. L., Ahuriri-Driscoll, A. L., Lea, M. G., & Lea, R. A. (2007). Whakapapa–a foundation for genetic research? Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 4(1), 43-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-007-9033-x

Leoni, G., & Pōtiki, M. (2019). Academic writing and translation in Te Reo Māori. Contemporary Research Topics, 5, 29-35. https://doi.org/10.34074/scop.2005004

Marsden, M. (2003). The woven universe: Selected readings of Reverend Māori Marsden. Te Wananga o Raukawa.

Mead, H. M. (2016). Tikanga Maori (Revised edition): Living by Maori values. Huia Publishers.

Ministry of Education. (2011). Tātaiako: Cultural competencies for teachers of Māori learners. https://teachingcouncil.nz/assets/Files/Code-and-Standards/Tataiako-cultural-competencies-for-teachers-of-Maori-learners.pdf

Moeke-Pickering, T. M. (1996). Maori identity within whanau: A review of literature. University of Waikato.

Mulholland, M. (2009). Beneath the Māori moon. An illustrated history of Māori rugby. Huia Publishers.

O’Carroll, A. D. (2013). Virtual Whanaungatanga: Māori utilizing social networking sites to attain and maintain relationships. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 9(3), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011300900304

Pihama, L., Cram, F., & Walker, S. (2002). Creating methodological space: A literature review of Kaupapa Māori research. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.14288/cjne.v26i1.195910

Pitama, D., Ririnui, G., & Mikaere, A. (2002). Guardianship, custody and access: Māori perspectives and experiences. Australian Indigenous Law Reporter, 7(4), 80-89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44656055

Roberts, M. (2013). Ways of seeing: Whakapapa. Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies, 10(1), 93-120. https://doi.org/10.11157/sites-vol10iss1id236

Sadler, H. (2007). Mātauranga Māori (Māori Epistemology). International Journal of the Humanities, 4(10), 35-45.

Smith, G. H. (1997). The development of Kaupapa Māori: Theory and praxis [Doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland]. ResearchSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/2292/623

Smith, G. H. (2003). Kaupapa Maori theory: Theorizing indigenous transformation of education and schooling [Paper presentation]. Kaupapa Maori Symposium-NZARE/AARE Joint Conference, Auckland, New Zealand.

Smith, G. H. (2015). The dialectic relation of theory and practice in the development of Kaupapa Maori Praxis. In L. Pihama, S-J Tiakiwai, & K. Southey (Eds.) Kaupapa rangahau: A reader (2nd ed., pp. 17-27). Te Kotahi Research Institute.

Te Huia, A. (2015). Perspectives towards Māori identity by Māori heritage language learners. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 44(3), 18- 28.

Te Rito, J. S. (2007). Whakapapa: A framework for understanding identity. MAI Review, 2, Article 2.