Tom Vahid1, Tanya Rütti1, Zinette Bergman2, Manfred Max Bergman2, 3

1 Scort Foundation

2 Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel, Switzerland

3 Department of Family Medicine, University of Michigan, USA

Citation:

Vahid, T., Rütti, T., Bergman, Z. & Bergman, M.M. (2024). Evaluating the Impact of Sport for Development Activities on Children through Observational and Visual Data Collection and a Guiding Framework. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

In this paper we explore the extent to which visual data collection methods, such as drawings and videos, can contribute to studying how vulnerable children benefit from participating in sport for development (SFD) activities. We first highlight the limitations of traditional data collection methods (e.g., surveys and interviews) in assessing the potential impact of activities on the well-being of children participating in SFD and then explore opportunities arising from integrating digital data formats that facilitate data collection methods for monitoring, evaluation, and research. In this context, we present a framework to illustrate how visual methods could be applied to collect and analyze the impact of an intervention. By capturing individual, relational, and institutional benefits that children gain from attending sports activities, this framework provides one example of how the positive impact of such activities can be systematized in a way that provides empirical evidence to support the multidimensional effectiveness of using sport as a tool for development. While recognizing their advantages, the paper also acknowledges areas of caution and potential limitations associated with visual data collection methods. The aim of our paper is to illustrate the potential of a tool that SFD practitioners can use to systematically collect and analyze visual data for assessing the impact of an intervention.

INTRODUCTION

The past two decades have witnessed an increased recognition of the positive contribution sport can make in a development context (Collison et al., 2019; Darnell, 2012; Kidd, 2008; Levermore & Beacom, 2009; Morgan et al., 2021; Schulenkorf et al., 2016). Effectively organized sport activities create an environment where, apart from obvious health benefits, children can learn, play, and interact in ways that positively contribute to their physical, emotional, and social development. However, providing evidence for such multidimensional impacts can be challenging. Consequently, the increased recognition of sport for development (SFD) has been accompanied by calls for greater evidence regarding the impact of these interventions (Adams & Harris, 2014; Coalter, 2007; Whitley et al., 2020), which, in turn, has generated an increasing focus on monitoring and evaluation (M&E) methods that may achieve this.

Numerous stakeholders, including researchers, policymakers, government officials, businesses, educational institutions, development agencies, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)/Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs), and civil society have employed M&E to gather evidence on how initiatives function and to better understand their impact (UN, 2021). Within the field of SFD, the United Nations (UN) provides a useful framework for defining the scope, purpose, and usefulness of M&E. In their Sport for Development and Peace Monitoring and Evaluation Toolkit (2021), the UN differentiates monitoring from evaluation. Monitoring refers to “the regular, systematic, collection and analysis of information related to a planned and agreed program or action [to provide] evidence of the extent to which the program is being delivered as intended” (UN, 2021, pg. 7). Evaluation in contrast refers to

a systematic assessment with a high level of impartiality (avoiding conflict of interest and biases) of an activity, project, program, strategy, policy, theme, operational area of institutional performance, amongst others. [To] provide information that is credible, reliable and useful […] to determine the relevance and fulfillment of objectives, development efficiency, effectiveness, [and] impact (UN, 2021, pg. 8).

Accordingly, evaluating empirically the multidimensional impact of a sports-based intervention focusing on vulnerable children in a development cooperation context requires a four-step approach: conceptualizing a context-specific and culture-sensitive data collection procedure; rigorous data collection that captures in multiple ways and across multiple events the program impacts; systematic analyses of the collected data that are suitable for the program, evaluation, and data collected; and a synthesis of the data analysis that reveals the program’s relevance, fulfillment of objectives, efficiency, and effectiveness (UN, 2021).

M&E Approaches to Collect and Analyze SFD Data

Traditional M&E approaches are usually divided into two types: quantitative methods, which typically employ various kinds of surveys and quasi-experiments, and qualitative methods, mainly based on interviews but sometimes combined with non-participant observations. Most M&E approaches, especially those employing qualitative research methods, rely on experiential reports from stakeholders involved directly or indirectly in the SFD program. Stakeholders providing experiential data include program beneficiaries as well as family members or care providers, intervention or program coordinators or administrators, and community members who are in some way involved with or impacted by the program. Methods used to collect experiential (self-)reports include informal conversations, formal one-to-one or group interviews, focus groups, or open-ended written responses, including experiential or reflection diaries or essays (UN, 2021).

Numerous challenges are associated with experiential (self-)reports, specifically if the intervention beneficiaries are children (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2022; Datta & Pettigrew, 2013; Hunleth et al., 2022; Kooijman et al., 2022; Moore et al., 2015; Nixon et al., 2022). First, experiential or behavioral reports from beneficiaries or significant others tend to be subjective and prone to bias (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2022; Kooijman et al., 2022). Second, children’s development is influenced by external factors beyond the scope of the program, which complicates assessment of a program’s impact (Moore et al., 2015). Third, the heterogeneity among program participants and the variability in degree and type of participation, especially in a development cooperation context, makes it difficult to define or assess reliably baseline, intervention conditions, and outcome measures (Datta & Pettigrew, 2013; Hunleth et al., 2022). Finally, the power relations between data collectors and intervention beneficiaries, especially between adults and children, introduces data collection and data quality limitations (Hunleth et al., 2022; Nixon et al., 2022). For example, when conducting interviews with children, efforts can be made to make the data collection procedure less intimidating, such as integrating a trusted third party into the interview situation, building rapport with the child, reducing formalisms, integrating props, or adapting body language and language register (Hunleth et al., 2022). However, even if these strategies have created an interview situation where children are able and willing to participate narratively, they may still seek to please the adult by saying what they think the adult wants to hear (Kutroavatz, 2017; Ponizovsky-Bergelson et al., 2019). Finally, it is unlikely that a child would be able to communicate the effectiveness of a program as it relates to relational, institutional, or other such abstract levels. Adult-child power relations may be exacerbated further when the adult is an outgroup member or external to the SFD activity. For instance, what a child shares with someone they are familiar with (a care provider, peer, or program coordinator) may differ significantly from what they might say to someone they are less familiar with – irrespective of the efforts made to build trust and rapport within a short interview period.

Quantitative approaches aim to overcome some of the biases and power dynamics associated with qualitative approaches. They tend to rely on a range of performance measures, standardized assessment tools, and surveys. Interventions that are less focused on the physiological benefits of an intervention frequently employ surveys, which may include quasi-experimental designs or baseline/pre-intervention and post-intervention measures, as well as field experiments (UN, 2021). Often designed to assess concrete development and program targets, these methods are valued for their ability to identify and measure change among SFD beneficiaries. If validated instruments, such as Rosenberg’s (1965) self-esteem scale or Smith et al.’s (2008) survey about resilience are employed, they may provide cost-effective, reliable, and often cross-culturally validated evidence of intervention success from a large number of respondents. While there are clear benefits in using established scales and surveys, they are not free from bias. Established scales, for example, require the focus of an intervention to be on what the scale was designed to measure. In addition, and like interviews, surveys are self-reports and can lead children (or adults) to knowingly or unknowingly misrepresent their knowledge, skills, and abilities (Dang et al., 2020). If an intervention aims at behavior or behavioral change, then most scales and surveys are limited to assessing behavioral reports, which diverge considerably from behaviors in many evaluation contexts. Finally, fundamental assumptions associated with survey research are that the items in the questionnaire pertain to the focus associated with the intervention, and that all respondents understand the questionnaire items, have the information required to respond to the items, are able and willing to respond to them truthfully, and do not differ significantly in how they decode the questions, irrespective of social group, developmental stage, religious affiliation and faith-based practices, etc. (i.e. respondents need to decode the questionnaire items the way the researcher intended them to be decoded, which assures that all respondents receive the same ‘stimuli’). Although efforts can be made to reduce potential biases associated with surveys (e.g., by using established scales or developing a valid instrument, training data collectors in data collection methods, establishing rapport and trust, reiterating the importance of honest feedback, granting anonymity and confidentiality, etc.), no data collection method is free of bias. Moreover, surveys require a certain level of literacy and degree of abstraction to understand and respond to a questionnaire, especially if it is designed to assess the impact of an intervention. Even if Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI), Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI), or Computer Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) is used to assist respondents with lower literacy levels, this approach can be time-consuming and might not be appropriate otherwise, depending on the characteristics of the SFD beneficiaries, the intervention, or the intervention context. Especially when self-reporting the effectiveness of an intervention by a beneficiary, such reports may tap into a subjective assessment or affective reaction, rather than reliable data pertaining to intervention outcomes.

Most of these challenges associated with traditional data collection methods are recognized within the SFD community (Levermore, 2011) and the broader non-profit sector (Innovation Network, 2016). Unsurprisingly, authors like Engelhardt (2019) have called on researchers and practitioners to be more open, and to experiment with different methods and tools (e.g., community mapping, drawings, storytelling, videos) to collect data that may be more effective in observing, evaluating, or monitoring the impact of SFD activities in a systematic and useful manner. We concur with Engelhardt, and a central component of this paper is to expand the repertoire of data collection methods to include observational and visual data for the evaluation of SFD activities for vulnerable children. The aim of our paper is to illustrate to SFD practitioners the potential of using these tools to systematically collect and analyze visual data for assessing the impact of an intervention.

Observational Methods and Visual Data Collection Methods in SFD

Participant or non-participant observational methods, conducted by an intervention coordinator or an external researcher, refer to a group of research methods that are based on data that, first, can be directly observed or experienced by a data collector and, second, that will be systematically analyzed and interpreted in line with what was observed and experienced (Ciesielska et al., 2017). Observational methods are much less frequently employed in M&E (Abbato, 2023; Borg, 2021), yet they are especially attractive because they have the potential to provide a direct way of assessing the impact of a program and its benefits. While relying heavily on the interpretation of the observed behavior, interviews and surveys are equally burdened by interpretation, as such data also has to be analyzed and interpreted. Observational methods may be as time and resource intensive as more conventional data collection methods, such as interviews (Westbrook & Woods, 2009). Resource constraints often limit the time spent in the field, which in turn restricts the scope and reliability of observational data. According to Boyko (2013), this delimits the contribution of observational methods as observational ‘snapshots’ are insufficient to assess the association between SFD program activities and goals. The ability to directly observe SFD activities from various angles before, during, and after an intervention nevertheless provides immense opportunities to capture nuances of SFD programs that are difficult to match through (self-)reports. Given the different advantages and disadvantages of experiential reports and observations, a combination of observational methods and experiential reports when studying the impact of an SFD intervention improves on the limits imposed by any single data collection method (Christensen et al., 2022; Holtrop et al., 2022; Gamarel et al., 2021; Odendaal et al., 2016).

Visual data collection methods, sometimes also referred to as art-based methods (McMahon, 2017), include methods that employ drawings, posters, maps, photos, and videos (Phoenix, 2010). While these methods have remained at the margins of social science for decades, they have become more popular (Jewitt, 2012; Phoenix, 2010) due to the so-called visual turn in the social sciences, the rise of social media, and advances in the analysis of non-numeric and non-textual data. Numerous studies have begun to explore the potential of using these methods in SFD: Kuhn (2003) and Noonan et al. (2016), for example, used drawings to explore children’s perceptions around physical activity, while van Ingen (2016) used paintings accompanied by text to explore the thoughts and experiences of survivors of gender-based violence during a boxing and art-based project. Sobotová et al. (2016) used participatory mapping to explore perceptions of security in relation to spaces where sport and art-based activities take place. Numerous studies integrate photography to capture and encourage individuals to express their thoughts and experiences of participating in sport-based activities (Hayhurst, 2017; McSweeney et al., 2022; Strachan & Davies, 2015), explore the barriers to participating in physical activity (Rivard, 2013), or document changes in children’s nutritional behavior (Bush et al., 2018). Video-based data has been used to collect and showcase stories from participants (Asadullah & Muñiz, 2015). Furthermore, Bean et al. (2018) assessed program quality in youth sport and recommended that future studies might also benefit from the recording of videos to support the observational process. Our work builds on this growing body of practices. We showcase the potential of two data collection methods that have shown significant promise in expanding the scope of M&E to monitor the impact of SFD activities and highlight the benefits for participating children.

Drawing as an M&E Data Collection Technique

Drawings provide children with a medium to express their thoughts and feelings (Kuhn, 2003; Moskal, 2017; Noonan et al., 2016). When evaluating the impact of SFD activities, children’s drawings can offer valuable insights into the reasons why children participate, what they like or dislike, and how they integrate intervention activities into their thought patterns. For instance, at the end of an activity, children can be encouraged to draw what they liked most about it. Subsequent conversations about their drawings, known as episodic interviewing, help clarify aspects of the activity that elicit the children’s interests and why they are interested in specific aspects. Such data can not only be used to study the impact of an activity but also how to improve this activity. Using drawings as a visual method has many advantages, particularly when working with children, as this method helps reduce power imbalances encountered in traditional interviews, especially because the child uses as their reference point the drawing, rather than the question by the interviewer (Søndergaard & Reventlow, 2019). Furthermore, the child at least partially replicates in their narrative associated with the drawing some thoughts and emotions they had while drawing the picture, rather than having to produce thoughts and emotions as an answer to an interview question (Rose, 2022; Water et al., 2018). Using a drawing as the focal point of a discussion is a child-friendly way to reduce potential stressors, helping to minimize the formality of capturing children’s thoughts, emotions, and experiences (Rose, 2022). Allowing children to explain their drawings in their own words can, furthermore, help to avoid misinterpretations (Kuhn, 2003; Noonan et al., 2016) and provides in-depth data for analyzing the impact of SFD activities. Additionally, utilizing children’s drawings safeguards the child’s perspective from being lost or taken out of context during the analysis process (Merriman & Guerin, 2012; Søndergaard & Reventlow, 2019). Apart from drawings as a visual data collection tool, we now turn to the utility of collecting video data for M&E.

Videos as an M&E Data Collection Technique

The widespread proliferation of smartphones and social media across the globe presents a unique opportunity for introducing visual methods of data collection for M&E of SFD programs and activities (Shaw et al., 2021). The ubiquity of smartphones has normalized the practice of taking pictures and making videos in everyday life, thus replacing traditional debates that emphasized the invasiveness and potential bias associated with this kind of data (Asan & Montague, 2014; Nassauer & Legewie, 2019; Robson, 2011). We have observed this in our own M&E activities. Despite initial concerns that video recording with a smartphone during SFD activities would influence the children’s behavior, their attention was quickly recaptured by the SFD activities, even in extreme field contexts such as orphanages and refugee camps. This could be due in part to the continuous presence of smartphones in the lives of children and the ability to collect high-quality video data using appropriately equipped smartphones, rather than employing bulky camera equipment. Rosenstein (2002) also notes that, through her experience of using video, both adults and children respond in a similar way if there is an in-person observation taking place: They are initially self-conscious of the camera or observer, but they soon forget that they are being observed. Video-based observations are even less distracting and intimidating if they are conducted by someone familiar to the child, which highlights the potential for involving SFD practitioners or coordinators in the data collection process (Asan & Montague, 2014). Our own fieldwork confirmed that almost all people involved in SFD activities, such as staff, coordinators, or coaches, use smartphones, which means that SFD staff could support data collection efforts alongside their SFD program roles. While this required training in data collection, it yielded greater buy-in to the M&E process, empowered staff, and improved the scope and quality of the data for the evaluation of the program.

When collecting video data involving children, ethical considerations deserve detailed discussion. It is important to acknowledge, for example, that there are several risks associated with digitalizing observational data (Facca et al., 2020; Rutanen et al., 2018). Video-based observations create a visual record of activities that cannot fully obscure individual identities, locations, and behaviors, even when findings are reported in a way that do not connect the individual to the evaluation and report (Facca et al., 2020; Rutanen et al., 2018). Therefore, obtaining consent is essential for any video data collection, which has its own set of challenges in a development cooperation context and with children (Facca et al., 2020). Additionally, because visual data can be easily copied and shared (Mok et al., 2015), organizations, practitioners, and researchers must take rigorous measures to protect the data, including the use of secure servers (Rutanen et al., 2018). Staff or volunteers supporting the data collection process should be well-trained in handling data to ensure privacy and data protection rights (Rutanen et al., 2018). This becomes even more crucial when working with vulnerable groups or on sensitive topics because disclosing data or revealing identities could jeopardize the participant’s safety and welfare (Rutanen et al., 2018).

In addition to data protection and privacy concerns, it is essential to consider the cultural appropriateness of collecting visual data, such as videos or photos (Schulenkorf et al., 2020). Ethical data collection requires embedding methods within the local context and cultural norms (Facca et al., 2020). This applies to all methods of data collection, but arguably more so when it comes to visual representations of people, behaviors, and personal or community spaces, which usually reveal much more than a simple tick on a questionnaire (Facca et al., 2020). This reveals an advantage of the method because culturally sensitive data collection requires a systematic and in-depth exploration of the ‘inside view’ to ensure interpretations are grounded in local cultures and embedded in participants’ perspectives (Denzin & Lincoln, 2017; Schulenkorf et al., 2020). Collecting visual data, especially using videos, allows us to move beyond isolated snapshot-observations. While not free from a culturally-biased gaze, they nevertheless allow us to more systematically study the cultural and contextual embeddedness of participants.

Another area of caution relates to the analysis process, which might have contributed to the limited use of videos in the context of M&E. Quick and easy video recording on smartphones often leads to the temptation of capturing numerous or lengthy videos to cover everything comprehensively. However, managing large amounts of unfocused data becomes time-consuming, requires substantial storage space, and can be expensive to review and analyze, while coding and analyzing video data can be challenging, necessitating training and expertise (Dash et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2014).

Drawing from our experiences, incorporating ethical data collection approaches, such as using video, audio, drawing, and storytelling with children for M&E of SFD programs, can significantly enhance the observation and evaluation process within the SFD context. Especially when expanding observational methods to include different visual data collection methods in SFD, there is the potential to overcome some of the limitations outlined earlier. Unlike most observational methods during field visits, which are often constrained in time and scope, video data allows for recording entire SFD activities across different sites and observation periods. Instead of reducing observations to field notes or predetermined observation grids, videos capture children’s participation in SFD activities as natural occurrences, providing insight into the child within their context, social interactions between the child and others (including other participating and non-participating children, care providers, intervention coordinators, community members, etc.), and the context within which the activity is taking place. This has multiple benefits, including overcoming the restricted scope of one-off field visits without requiring a substantial increase in time and resource investments. Multi-site, prolonged, and repeated visits could assist in observing changes, establish systematic connections between SFD activities and program goals, and mitigate researcher bias through collaborative reviews of video data by a combination of multiple researchers. Video data can also be reviewed and discussed in a participatory manner with practitioners and participants of the SFD program (Borg, 2021; Rosenstein, 2002). This approach helps to address potential misinterpretation by outsiders, while also fostering ownership, buy-in, making the M&E process more inclusive, and generating ideas for program improvement.

In sum, the need to observe, evaluate, and monitor the impact of SFD activities in a systematic and useful manner is growing. Traditional qualitative and quantitative approaches in M&E, such as interviews and surveys, face numerous challenges when applied in SFD programs involving children, especially in a development cooperation context. While observational methods offer a more direct way to assess the impact of SFD activities on children, they are frequently limited in time, scope, and necessity to interpret observations by outsiders. To address this, and in line with Engelhardt’s appeal to widen the scope of data collection methods in SFD (2019), we propose expanding the repertoire of M&E methods to include a toolkit that integrates visual and observational data collection methods as a complement to traditional evaluation methods, particularly in SFD contexts involving vulnerable children.

Frameworks to Assess the Impact of SFD Activities

Thus far, we have focused on the first component of M&E: the collection and analysis of data to observe, evaluate, and monitor the impact of SFD activities. This section is dedicated to exploring the second component of M&E, which relates to evaluation. As outlined earlier, the goal of evaluation is to employ a framework to assess the impact of SFD activities in relation to program goals in a way that is systematic, credible, reliable, and useful. In most instances, a clear line exists between the intended objectives and goals of a program and its activities, making an evaluation framework a natural outcome of clearly articulating and assessing this connection (Bao et al., 2015; Kusek & Rist, 2004).

Various frameworks have captured the wider benefits of SFD activities. For example, the Human Capital Model (Bailey et al., 2013; Whitehead et al., 2012) provided a valuable overview of physical, emotional, individual, social, financial, and intellectual benefits associated with physical activity, sports, and physical education. The UK based Sport for Development Coalition (2015) presented The Outcomes Model which identified four areas of outcomes associated with SFD activities i.e. social, emotional and cognitive capabilities; individual achievements and behaviors; interpersonal relationships; and benefits to society. Furthermore, the Commonwealth Secretariat (2020) developed a toolkit to measure the benefits of sport by creating direct links to the global Sustainable Development Goals. The above frameworks reinforce the desire and rationale within the SFD community to better capture the wider benefits of sport both at a local and international level.

The remainder of this paper will present an evaluation framework developed by Bergman & Bergman (2020) which complements the above models. This framework was designed using observational and visual methods. The goal was to better understand the expansive benefits children gain from SFD activities, and to support practitioners and researchers with a practical tool to collect and analyze these benefits.

Development and Application of the IRI-Framework

The Scort Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Switzerland that implements SFD programs in crisis and former conflict regions. Scort, together with local and international partners, train young adults (referred to as Young Coaches) in their respective countries who then deliver SFD activities for vulnerable children. Although Scort already assessed how Young Coaches benefit from this training (referred to as the Young Coach Education Program), there was a need to better understand how children benefit from the SFD activities delivered by these trained coaches. Although the positive impact of the SFD activities on children seemed obvious to Scort and other stakeholders, it was difficult to evidence the presumed benefits due to several challenges: First, Scort’s focus lies in training and assessing Young Coaches, with children being the indirect beneficiaries. Second, part of the data collection on the benefits children gain from Young Coaches SFD activities would need to be conducted through partner organizations or Young Coaches. Third, the involvement of various stakeholders globally (through partner organizations and Young Coaches) made standardized data collection impossible, given the sometimes weekly changes of intervention context within and between sites. Fourth, carrying out SFD programs in various crisis and former conflict regions introduces cultural and contextual dynamics that profoundly impact the form and function of each program. While the program’s adaptability to changing dynamics is one of its strengths, conducting a systematic M&E across different settings to understand its impact is challenging. Fifth, the composition of the participants change based on gender, migration background, ability, ambition, disability status, religious and cultural practices, etc. These changes differ not only between sites but also within sites and between sessions. To better understand how children benefit from participating in SFD activities, Scort needed an evaluation framework that could accommodate a wide variety of parameters while concurrently conceptualizing and assessing a broad set of possible benefits.

As a response to this set of requirements, the IRI-Framework was developed between 2018 and 2020 (Bergman & Bergman, 2020), and funded by Fondation Botnar. The development of the IRI-Framework began as a systematic review of the academic literature on intervention studies that use modern, non-conventional, non-survey-based evaluation methods, tools, and instruments when working with children in various development cooperation contexts or a combination thereof. Examples of non-conventional approaches that were reviewed include ethnographic studies, sociological life-world analyses, psychological studies on interactions with and between children, and systematic, direct observations (e.g., Ager et al., 2014; Barrios, 2014; Bell & Bell, 2017; Ben-Arieh, 2006; Johnston, 2008; Kuhn, 2003; Pfadenhauer, 2005; Sleijpen et al., 2016). A specific emphasis was placed on reviewing approaches that employ writing and drawing exercises, narrative and self-report measures, as well as projective techniques as data collection methods to explore the potential of developing episodic interviewing with children (for example, Backet-Milburn & McKie, 1999; Bland, 2018; Chorney et al., 2015; Deighton et al., 2014; Einarsdottir et al., 2009; Evans & Reilly, 1996; Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016; Noonan et al., 2016). Behavioral observation strategies from the fields of education, child, social, and personality psychology were incorporated, along with measurement methods used in applied developmental psychology, pedagogy, ethnography, and needs and risk assessment approaches in community and refugee studies (see, for example, Ben-Arieh et al., 2001; Campbell et al., 2016; Gifford et al., 2007; Hart, 2009; Robinson et al., 2014; Tol et al., 2011; Volpe et al., 2005). Finally, reviews of studies in the field of sports sciences that use novel approaches to understanding how participation in sports benefits children and adolescents physically, psychologically, and socially (such as Eime et al., 2013; Holt et al., 2011; Whitley et al., 2016) completed this phase of framework development (see Bergman & Bergman, 2020 for a more detailed description of this phase). In a second step, the initial, literature-based framework was complemented with site visits to the Young Coaches’ activities to identify which aspects of child well-being could be observed in situ. The site visits were significant to the development of the evaluation because they allowed the initial IRI-Framework to be tested and refined in a variety of geographic, cultural, and national contexts. In total, local and international collaborators collected data during 27 observation periods in India, Mexico, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. While the first third of observation periods were used to supplement the evaluation scope of the IRI-Framework in terms of range, appropriateness, and usefulness, subsequent data collection periods, which included observational, visual, and interview data, were used to evaluate the benefits associated with the Young Coaches’ regular activities with children. Ultimately, the benefits captured by the IRI-Framework were consistently observable during SFD activities, irrespective of the local context within which they took place. The following is a summative overview of the IRI-Framework:

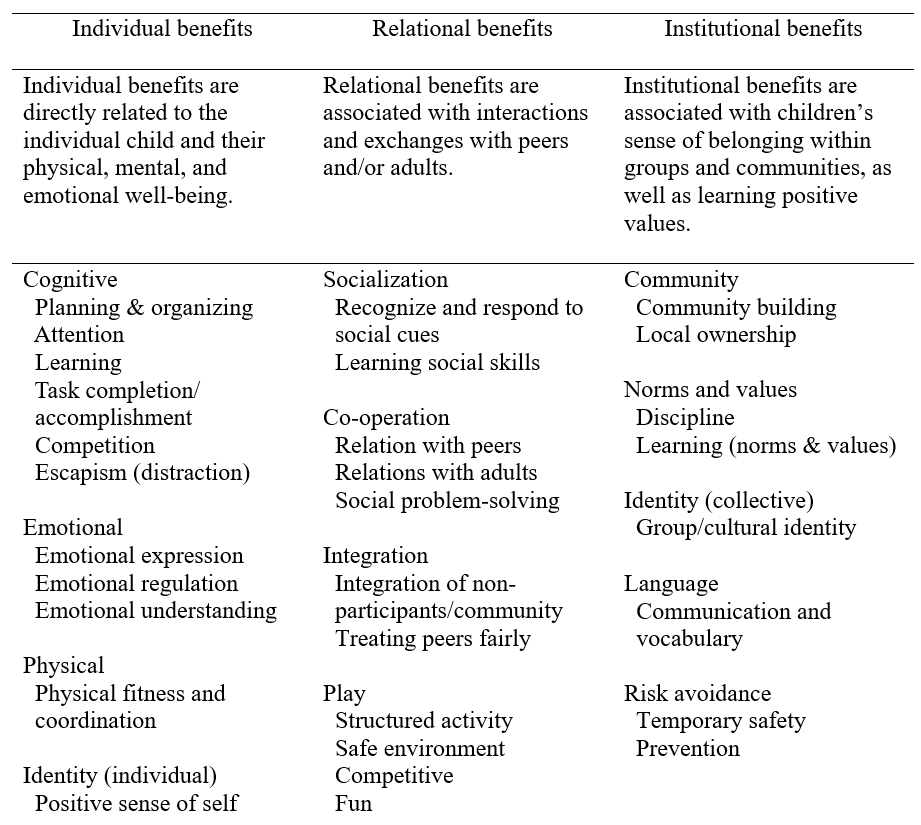

Table 1 – IRI-Framework Overview

The IRI-Framework identifies three core levels of benefits for children that relate to individual (e.g., cognitive, skills), relational (e.g., communication between peers, turn-taking, cooperation), and institutional (e.g., social norms, cultural values) benefits. Each of these are formed of at least four sub-categories as illustrated in Table 1. The benefits associated with each level can overlap, as can the benefits between the levels. At times, clear distinctions were made for conceptual, illustrative, and analytic purposes, despite the frequent interrelations between benefits. This also helps ensure that benefits may be explored separately and more systematically from different disciplinary or need-based perspectives in the future.

As the IRI-Framework presents a variety of observable benefits in SFD activities for children, it provides a useful tool that can support researchers and practitioners in systematically building, structuring, and refining their evaluation of SFD organizations. Below, we highlight several strategies of how this can be done.

The IRI-Framework to Guide and Complement Data Collection

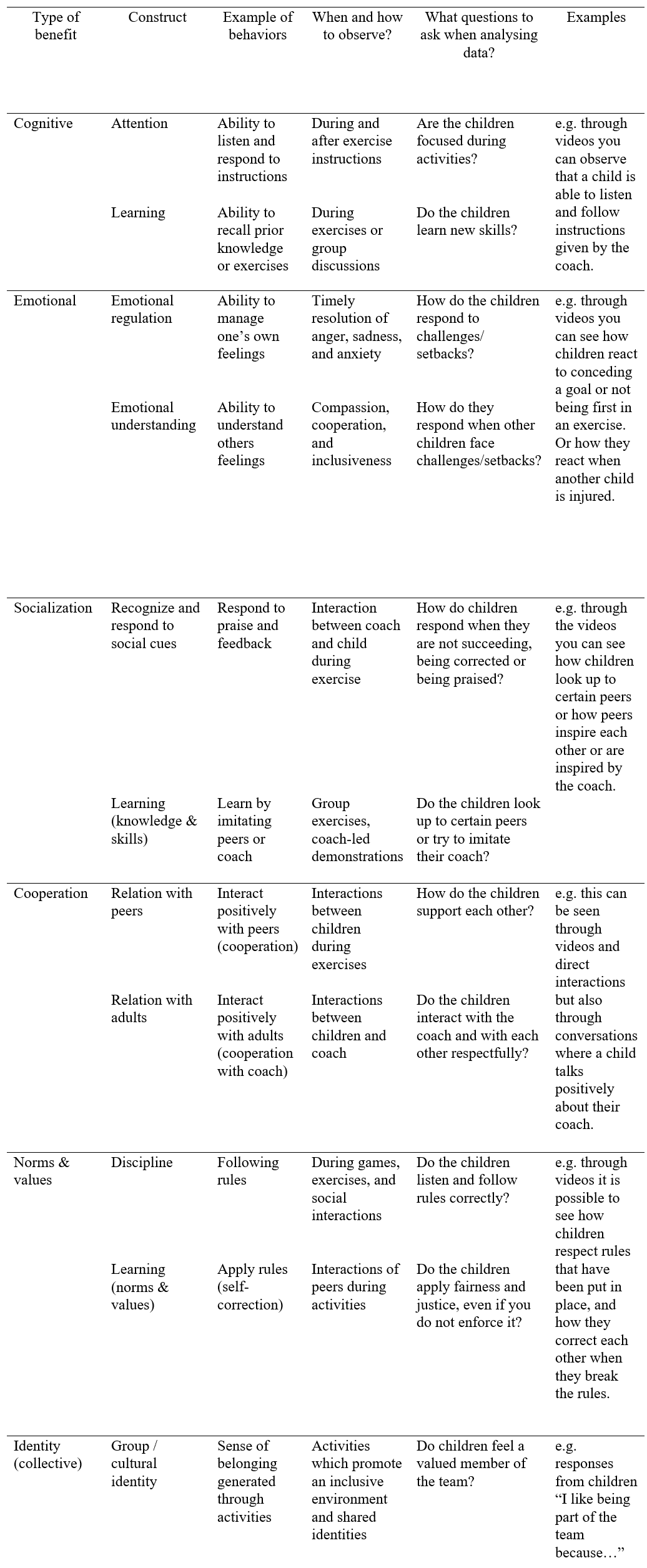

Especially in combination with visual data collection, the IRI-Framework can be used to develop a focus for research, evaluation, monitoring, or implementation, and, accordingly, select and structure the data collection and analysis process. This can help reduce the amount of video recordings, given a clear focus between intention, data collection, and data analysis, thus streamlining a specific project. For example, a SFD program aiming to evaluate how a specific activity or coach impacts the children can use the IRI-Framework to select focal topics, such as how socialization and cooperation connect to relational benefits (Table 1, Column 2). Based on this focus, they can collect observational data by making short videos of the coach interacting with children, as well as interactions between peers. The IRI-Framework can then guide the analysis. Specifically, the researcher or practitioner can review the videos using sample questions, detailed in Table 2 of the IRI-Framework below (see Column 5, Rows 5 to 8) to prompt their analysis. Accordingly, questions such as: “How do the children support each other?” and “How do the children interact with the coach and with each other respectfully?” can be used to focus and structure the analysis. Equally, if a researcher or practitioner wanted to study individual benefits to the children (as listed in Column 1 of Table 1), they may decide to focus on cognitive and affective benefits by collecting video data similar to the process outlined above. In this case, their analysis would be guided by questions such as “What focuses or distracts children’s attention during activities?”, “Who or what refocuses children’s attention to the tasks?”, or “How do children internalize acquired knowledge or practices, and how do they disseminate this effectively to their peers?” (as shown in Table 2, Row 1, Column 5).

Table 2 – Selected Examples from the IRI-Framework

The IRI-Framework to Identify New or Unexpected Impact

While defining specific focal points a priori to guide data collection and analysis focuses a conventional evaluation, such a priories also narrow the scope, potentially missing unexpected elements that emerge during SFD activities. And it is not only new discoveries that make this form of assessment interesting. It is also well-known benefits, such as learning turn-taking, that can be studied in situ, for example as the establishment of justice over strength as a norm (institutional benefit) that leads to the practice and monitoring of turn-taking among peers (relational benefit). The IRI-Framework can also be used to explore the overall impact of an SFD program by assisting researchers and practitioners in identifying unanticipated benefits arising from a program’s activities or by adapting the program or practice to enhance certain benefits. During the evaluation of the Scort program, the IRI-Framework revealed several unexpected findings. These included the cascading positive impact on Young Coaches and the larger community, indicating that the benefits experienced by the children extended to bring about advantages for others as well. Established SFD activities within a communal space create an ecosystem that fosters inclusion by temporarily suspending differences in skill levels, ambition, age, gender, disability status, religious and cultural orientation, or social background among participants. This dynamic spilled over into the immediate environment, where older children congregated to watch the activities, parents and other care providers intermingled and coordinated future activities, and, at many SFD activity sites, small venders set up market stalls that attracted many members of the community just before, during, and just after the SFD activity. These examples illustrate how a broader application of the framework can help articulate more abstract and difficult-to-observe impacts, such as those related to institutional benefits, including language, norms, values, and community building.

The IRI-Framework to Enable Internal Learning

The framework can support the internal learning processes of a SFD program by using the video-based observations to understand how improvements could be made in its delivery. Building on the previous example of cognitive benefits relating to attention (Table 2, Row 1), researchers or practitioners could assess how a child’s experience and learning could be enhanced. A review of pertinent video material on attention could improve the design of the program itself, it could be used to assess and improve on how coaches deliver instructions and monitor specific activities, and it could help coaches through self-reflection to improve their own practice on developing attention in a group that diverges considerably in age, psychological development, ambition, ability, etc.

Using the IRI-Framework to Raise Awareness and Disseminate Findings

The IRI-Framework can also assist in selecting video scenes that not only add value to the collection and analysis of data but that can be used to raise awareness about SFD activities. In particular, videos provide a visual experience, bringing activities to life, and can more effectively convince parents, teachers, and funders of the associated benefits. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, video-based activities brought SFD activities into the homes of families around the world. One of our partners explained that “parents have been feeding back that they didn’t realize that the activities were so much more than [playing] football”. Furthermore, selected scenes can help disseminate findings about the benefits associated with activities to a wider audience. Written reports that often follow in-person observations, surveys, or interview findings, are not always accessible to audiences with low literacy levels, may not be translated into the local language, or could be inaccessible due to jargon. Thus, the use of videos can be engaging and informative and the IRI-Framework can help select which scenes could best reveal visible benefits, understandable to all.

The IRI-Framework to Make Explicit Connections between Monitoring, Evaluation, and Dissemination

The IRI-Framework is useful at all stages for video-based observations in a SFD context, including the selection of focal points, collection of data or selecting a subset from existing data that relates to the selected focal points, analyzing the data in relation to the focal points, and disseminating findings to different stakeholders, including funders, care providers, participating or not-yet participating children, NGOs/NPOs, or researchers. Furthermore, it can easily integrate visual methods such as children’s drawings. For instance, when analyzing the drawings and corresponding conversations with children, the framework can help associate observational, visual, and verbal data with specific benefits. When asked to draw what they liked most about that day’s activity, children participating in the activities delivered by Young Coaches often drew or talked about specific exercises, the skills they learned associated with the exercises, and how this helped them do well in the practice. Children thus highlight the learning impact of an activity (Table 2, Row 1), and this relates to a number of benefits, including retention, recall, awareness of accomplishment, awareness of the benefits of learning, and pride in accomplishment. When children draw players and explain that they enjoyed being a member of a team, even of a team that did not do well in a set of exercises on that day, the IRI-Framework can help reveal how children benefit from the activity in terms of peer-to-peer cooperation and friendship bonds, as indicated in Table 1, Column 2 and Table 2, Row F. Children often drew their team jersey or badge, and during conversations about their picture reinforced the sense of belonging and team aspiration that was fostered by team activities. This can be associated with a positive group identity and its benefits, as shown in Table 1, Column 3 and Table 2, bottom row.

In the analysis process, the IRI-Framework can help establish themes in drawings and conversations and relate them to associated benefits outlined in the framework. The effort of decoding and describing the impact of the activities can contribute to disseminating the benefits of an SFD program, including any communication to specific stakeholder groups or a wider public. For example, in a report, pairing a drawing with a key quote from the child can help explain the benefits the child enjoyed as part of their participation.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Most people involved in SFD programs are well aware of the immediate and overall benefit of participation. However, it is quite challenging to assess or communicate to relevant stakeholders the multidimensional nature of these benefits, especially with vulnerable children in a development cooperation context. This paper presents some of the limitations associated with traditional forms of data collection employed in M&E of SFD programs, such as surveys and interviews, and explores the potential of including more creative methods, such as visual and video-based observation methods. Specifically, we discuss how visual data collection methods, such as drawings and videos, could complement existing data collection methods in SFD contexts, especially when involving vulnerable children. The widespread proliferation of smartphones and social media presents a unique opportunity to introduce video-based observational methods. Similarly, the ubiquity of children’s enjoyment of drawing presents an excellent opportunity to include visual methods in M&E of SFD programs. As demonstrated in this paper, these methods are highly versatile and adaptable to data collection, analysis, and reporting in complex evaluation contexts. The integration of these approaches has the potential of researching new phenomena or new aspects of established phenomena, reach new audiences, strengthen research, evaluation, monitoring, and practices, and strengthen the understanding of the efficiency and effectiveness of sports for development well beyond the Global South or vulnerable populations. The employment of alternative methodological approaches has also proven to be effective in reducing the power relations between adults and children, which otherwise hinders the collection of reliable data.

Furthermore, the IRI-Framework, which explicitly identifies and helps to provide evidence for the multidimensional benefits of a complex SFD program, serves as a useful tool to achieve this. Beyond its immediate application, the IRI-Framework may serve as a guide for the conceptualization, data collection, and data analysis on how children and significant others may benefit from participating in SFD activities at intrapersonal, relational, and institutional levels. When used alongside visual or more conventional data collection methods, such as one-to-one or group interviews, focus groups, or surveys, the IRI-Framework has illustrated its potential to systematically gather evidence of the wide range of benefits that SFD activities have. Considering the scope of the IRI-Framework, it would be quite easy to adapt, pilot, and apply the framework to other target groups, including different age cohorts, psychological or physical disabilities, religious or cultural groups, etc. Furthermore, the IRI-Framework may also be a useful starting-point to explore programs and interventions beyond sports.

Overall, the IRI-Framework can help identify a study, intervention, evaluation, or monitoring activity, focus the data collection and analysis process based on this focus and activity, loosen conceptual limitations, sharpen observation skills, and structure dissemination and communication elements of a project.

The paper also makes an argument for the utilization of digital tools when presenting and reporting on a project. We are living in a highly visual and visualized world. Accordingly, observational and visual methods can make findings more appealing, accessible, and memorable to a wider audience. Visualizations in the form of exemplars or findings can raise awareness of SFD program successes, advocate for support, and promote coordination and networking between stakeholders and partners. Our fieldwork has also clearly demonstrated that visual evidence is highly effective with SFD participants, program staff, and program coordinators. Collecting, displaying, and illustrating findings visually provided information and feedback to program coordinators, staff, and participants in ways that are very difficult to achieve with tables, figures, and statistical coefficients.

However, we fully acknowledged that there are additional challenges when collecting and analyzing data beyond well-established scales and quasi-experimental designs. Beyond ethical concerns relating to consent, privacy, anonymity, confidentiality, and data protection, the obvious limitations of non-standardized procedures include difficulty of replication and well-trodden paths associated with validity concerns. This is not the place to rehearse yet again the advantages and disadvantages of qualitative versus quantitative research and evaluation designs. Instead, we hope to have made an important contribution to the qualitative evaluation of ambitious and complex SFD programs, and we hope that future M&E projects either explore the extensions proposed here or, going a step further, reflect on the relatively unchartered territory of mixed methods design, specifically to integrate in SFD programs and their evaluation video-based observations and visual methods. It is our hope that this paper will inspire ideas and foster debates about how individuals and organizations, even those with limited M&E expertise, can approach the evaluation of their activities or projects. We strongly advocate for the value of incorporating observational and visual data collection methods. By doing so, we believe that a broader range of stakeholders, especially practitioners, can better assess the impact and benefits of programs and initiatives.

Acknowledgements

It is important to acknowledge the various organizations and individuals in India, Mexico, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda who have supported the data collection process and thus contributed to the development and testing of the framework and visual data collection methods.

Furthermore, the support provided by Fondation Botnar, the University of Basel, and the wider team at the Scort Foundation, which allowed the exploration of new approaches to assessing the benefits that children gain from the SFD activities around the globe is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

Abbato, S. (2023). Digital Evaluation Stories: A Case Study of Implementation for Monitoring and Evaluation in an Australian Community not-for-Profit. American Journal of Evaluation, 44(4), https://doi.org/10.1177/10982140221138031

Adams, A., & Harris, K. (2014). Making sense of the lack of evidence discourse, power and knowledge in the field of sport for development. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 27(2), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2013-0082

Ager, A. (2014). Methodologies and Tools for Measuring the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Children in Humanitarian Contexts: Report of a Mapping Exercise for the Child Protection Working Group (CPWG) and Mental Health & Psychosocial Support(MHPSS) Reference Group. Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.34914.94408

Asadullah, S., & Muñiz, S. (Directors). (2015). Participatory Video and the Most Significant Change. InsightShare. https://insightshare.org/resources/participatory-video-and-the-most-significant-change/

Asan, O., & Montague, E. (2014). Using video-based observation research methods in primary care health encounters to evaluate complex interactions. Informatics in Primary Care, 21(4), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.14236/jhi.v21i4.72

Backett-Milburn, K. & McKie L. (1999). A critical appraisal of the draw and write technique. Health Education Research, 14(3), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/14.3.387

Bailey, R., Hillman, C., Arent, S., & Petitpas, A. (2013). Physical activity: An underestimated investment in human capital? Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 10(3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.3.289

Bao, J., Rodriguez, D. C., Paina, L., Ozawa, S., & Bennett, S. (2015). Monitoring and Evaluating the Transition of Large-Scale Programs in Global Health. Global Health: Science and Practice, 3(4), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00221

Barrios, R. E. (2014). ‘Here, I’m not at ease’: Anthropological perspectives on community resilience. Disasters, 38(2), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12044

Bean, C., Kramers, S., Camiré, M., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Forneris, T. (2018). Development of an observational measure assessing program quality processes in youth sport. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1467304. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1467304

Bell, D., & Bell, L. (2017). Covert Assessment of the Family System: Patterns, Pictures and Codes. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.2458/v7i2.20322

Ben-Arieh, A. (2006). Measuring and monitoring the well-being of young children around the world (Report No. 2007/ED/EFA/MRT/PI/5). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147444

Ben-Arieh, A., Kaufman, N. H., Andrews, A. B., Goerge, R. M., Lee, B. J., & Aber, J. L. (2001). Measuring and Monitoring Children’s Well-Being (Vol. 7). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2229-2

Bergman, M. M., & Bergman, Z. (2020). Development and application of an evaluation and monitoring tool for Scort’s Young Coach Education Programme. Unpublished report, Social Research and Methodology Group, Department of Social Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Bland, D. (2018). Using drawing in research with children: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 41(3), 342–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1307957

Borg, S. (2021). Video–based observation in impact evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 89, 102007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.102007

Boyko, E. J. (2013). Observational Research Opportunities and Limitations. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 27(6), 642-648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.07.007

Bush, R., Capra, S., Box, S., McCallum, D., Khalil, S., & Ostini, R. (2018). An Integrated Theatre Production for School Nutrition Promotion Program. Children, 5(3), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5030035

Campbell, S. B., Denham, S. A., Howarth, G. Z., Jones, S. M., Whittaker, J. V., Williford, A. P., Willoughby, M. T., Yudron, M., & Darling-Churchill, K. (2016). Commentary on the review of measures of early childhood social and emotional development: Conceptualization, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.008

Caqueo-Urízar, A., Urzúa, A., Villalonga-Olives, E., Atencio-Quevedo, D., Irarrázaval, M., Flores, J., & Ramírez, C. (2022). Children’s Mental Health: Discrepancy between Child Self-Reporting and Parental Reporting. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100401

Chorney, J. M., McMurtry, C. M., Chambers, C. T., & Bakeman, R. (2015). Developing and Modifying Behavioral Coding Schemes in Pediatric Psychology: A Practical Guide. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(1), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu099

Christensen, J. H., Ljungmann, C. K., Pawlowski, C. S., Johnsen, H. R., Olsen, N., Hulgård, M., Bauman, A., & Klinker, C. D. (2022). ASPHALT II: Study Protocol for a Multi-Method Evaluation of a Comprehensive Peer-Led Youth Community Sport Programme Implemented in Low Resource Neighbourhoods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215271

Ciesielska, M., Boström, K. W., & Öhlander, M. (2018). Observation Methods. In M. Ciesielska & D. Jemielniak (Eds.), Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies: Volume II: Methods and Possibilities (pp. 33–52). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65442-3_2

Coalter, F. (2007). A wider social role for sport: Who’s keeping the score? Routledge.

Collison, H., Darnell, S. C., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (Eds.). (2020). Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace. Routledge.

Commonwealth Secretariat. (2020). Measuring the contribution of sport, physical education and physical activity to the Sustainable Development Goals: Sport & SDG Indicator Toolkit V4.0. https://production-new-commonwealth-files.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/migrated/inline/SDGs%20Toolkit%20version%204.0_0.pdf

Dang, J., King, K. M., & Inzlicht, M. (2020). Why Are Self-Report and Behavioral Measures Weakly Correlated? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(4), 267–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.01.007

Darnell, S. C. (2013). Sport for Development and Peace: A Critical Sociology. Bloomsbury.

Dash, S., Shakyawar, S. K., Sharma, M., & Kaushik, S. (2019). Big data in healthcare: Management, analysis and future prospects. Journal of Big Data, 6(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0217-0

Datta, J., & Petticrew, M. (2013). Challenges to evaluating complex interventions: A content analysis of published papers. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 568. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-568

Deighton, J., Croudace, T., Fonagy, P., Brown, J., Patalay, P., & Wolpert, M. (2014). Measuring mental health and wellbeing outcomes for children and adolescents to inform practice and policy: A review of child self-report measures. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-8-14

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2017). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (Fifth edition). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

Einarsdottir, J., Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (2009). Making meaning: Children’s perspectives expressed through drawings. Early Child Development and Care, 179(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430802666999

Engelhardt, J. (2018). SDP and Monitoring and Evaluation. In H. Collinson, S.C Darnell, R. Giulianotti & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace. Routledge.

Evans, W., & Reilly, J. (1996). Drawings as a Method of Program Evaluation and Communication with School-Age Children. Journal of Extension, 34(6). https://archives.joe.org/joe/1996december/a2.php

Facca, D., Smith, M. J., Shelley, J., Lizotte, D., & Donelle, L. (2020). Exploring the ethical issues in research using digital data collection strategies with minors: A scoping review. PLOS ONE, 15(8), e0237875. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237875

Fan, J., Han, F., & Liu, H. (2014). Challenges of Big Data analysis. National Science Review, 1(2), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwt032

Gamarel, K. E., Stephenson, R., & Hightow-Weidman, L. (2021). Technology-driven methodologies to collect qualitative data among youth to inform HIV prevention and care interventions. mHealth, 7. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-2020-5

Gifford, S. M., Bakopanos, C., Kaplan, I., & Correa-Velez, I. (2007). Meaning or Measurement? Researching the Social Contexts of Health and Settlement among Newly-arrived Refugee Youth in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 20(3), 414–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fem004

Haggerty, M. (2020). Using Video in Research with Young Children, Teachers and Parents: Entanglements of Possibility, Risk and Ethical Responsibility: Profiling Emerging Research Innovations. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1163/23644583-bja10005

Halle, T. G., & Darling-Churchill, K. E. (2016). Review of measures of social and emotional development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.02.003

Hart, R. (2009). Child refugees, trauma and education: Interactionist considerations on social and emotional needs and development. Educational Psychology in Practice, 25(4), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360903315172

Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2017). Image-ining resistance: Using participatory action research and visual methods in sport for development and peace. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 2(1), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2017.1335174

Holt, N. L., Kingsley, B. C., Tink, L. N., & Scherer, J. (2011). Benefits and challenges associated with sport participation by children and parents from low-income families. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(5), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.05.007

Holtrop, J. S., Gurfinkel, D., Nederveld, A., Phimphasone-Brady, P., Hosokawa, P., Rubinson, C., Waxmonsky, J. A., & Kwan, B. M. (2022). Methods for capturing and analyzing adaptations: Implications for implementation research. Implementation Science: IS, 17, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01218-3

Hunleth, J. M., Spray, J. S., Meehan, C., Lang, C. W., & Njelesani, J. (2022). What is the state of children’s participation in qualitative research on health interventions?: A scoping study. BMC Pediatrics, 22(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03391-2

Innovation Network. (2016). State of Evaluation 2016: Evaluation Capacity and Practice in the Nonprofit Sector. Innovation Network. https://stateofevaluation.org/

Jewitt, C. (2012, March 16). An Introduction to Using Video for Research. NCRM Working Paper (unpublished). National Centre for Research Methods. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2259/

Johnston, J. (2008). Methods, Tools and Instruments for Use with Children (Young Lives Technical Note 11). Young Lives. https://www.younglives.org.uk/publications/methods-tools-and-instruments-use-children

Kidd, B. (2008). A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society, 11(4), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430802019268

Kooijmans, R., Langdon, P. E., & Moonen, X. (2022). Assisting children and youth with completing self-report instruments introduces bias: A mixed-method study that includes children and young people’s views. Methods in Psychology, 7, 100102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2022.100102

Kuhn, P. (2003). Thematic Drawing and Focused, Episodic Interview upon the Drawing—A Method in Order to Approach to the Children’s Point of View on Movement, Play and Sports at School. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4,(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-4.1.750

Kusek, J. Z., & Rist, R. C. (2004). Ten Steps to a Results-Based Monitoring and Evaluation System: A Handbook for Development Practitioners. World Bank. Washington https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/84e1b3ba-74a2-5a19-a68d-a4b9632b74ad

Kutrovátz, K. (2017). Conducting qualitative interviews with children – methodological and ethical challenges. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 8(2), 65–88. https://doi.org/10.14267/cjssp.2017.02.04

Levermore, R. (2011). Evaluating sport-for-development: Approaches and critical issues. Progress in Development Studies, 11(4), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100405

Levermore, R., & Beacom, A. (2009). Sport and Development: Mapping the Field. In R. Levermore & A. Beacom (Eds.), Sport and International Development (pp. 1–25). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230584402_1

McMahon, J., MacDonald, A., & Owton, H. (2017). A/r/tographic inquiry in sport and exercise research: A pilot study examining methodology versatility, feasibility and participatory opportunities. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 9(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1311279

McSweeney, M., Otte, J., Eyul, P., Hayhurst, L. M. C., & Parytci, D. T. (2023). Conducting collaborative research across global North-South contexts: Benefits, challenges and implications of working with visual and digital participatory research approaches. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 15(2), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2022.2048059

Merriman, B., & Guerin, S. (2006). Using Children’s Drawings as Data in Child-Centred Research. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 27(1–2), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2006.10446227

Mok, T. M., Cornish, F., & Tarr, J. (2015). Too Much Information: Visual Research Ethics in the Age of Wearable Cameras. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 49(2), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-014-9289-8

Moore, T. G., McDonald, M., Carlon, L., & O’Rourke, K. (2015). Early childhood development and the social determinants of health inequities. Health Promotion International, 30(suppl_2), ii102–ii115. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav031

Morgan, H., Bush, A., & McGee, D. (2021). The Contribution of Sport to the Sustainable Development Goals: Insights from Commonwealth Games Associations. Journal of Sport for Development, 9(2), 14–29. https://jsfd.org/2021/09/01/the-contribution-of-sport-to-the-sustainable-development-goals-insights-from-commonwealth-games-associations/

Moskal, M. (2017). Visual Methods in Research with Migrant and Refugee Children and Young People. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 1–16). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_42-1

Nassauer, A., & Legewie, N. M. (2019). Analyzing 21st Century Video Data on Situational Dynamics—Issues and Challenges in Video Data Analysis. Social Sciences, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030100

Nixon, L. S., Hudson, N., Culley, L., Lakhanpaul, M., Robertson, N., Johnson, M. R. D., McFeeters, M., Johal, N., Hamlyn-Williams, C., Boo, Y. Y., & Lakhanpaul, M. (2022). Key considerations when involving children in health intervention design: Reflections on working in partnership with South Asian children in the UK on a tailored Management and Intervention for Asthma (MIA) study. Research Involvement and Engagement, 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-022-00342-0

Noonan, R. J., Boddy, L. M., Fairclough, S. J., & Knowles, Z. R. (2016). Write, draw, show, and tell: A child-centred dual methodology to explore perceptions of out-of-school physical activity. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3005-1

Odendaal, W., Atkins, S., & Lewin, S. (2016). Multiple and mixed methods in formative evaluation: Is more better? Reflections from a South African study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0273-5

Pfadenhauer, M. (2005). Ethnography of Scenes. Towards a Sociological Life-world Analysis of (Post-traditional) Community-building. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6,(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.23

Phoenix, C. (2010). Seeing the world of physical culture: The potential of visual methods for qualitative research in sport and exercise. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 2(2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.488017

Ponizovsky-Bergelson, Y., Dayan, Y., Wahle, N., & Roer-Strier, D. (2019). A Qualitative Interview With Young Children: What Encourages or Inhibits Young Children’s Participation? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919840516

Rivard, L. (2013). Girls’ Perspectives on Their Lived Experiences of Physical Activity and Sport in Secondary Schools: A Rwandan Case Study. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 3(4), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v03i04/53954

Robinson, S., Metzler, J., & Ager, A. (2014). A Compendium of Tools for the Assessment of the Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing of Children in the Context of Humanitarian Emergencies. Columbia University. http://www.cpcnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Measuring-Child-MHPSS-in-Emergencies_CU_Compendium_March-2014-.pdf

Robson, S. (2011). Producing and Using Video Data in the Early Years: Ethical Questions and Practical Consequences in Research with Young Children. Children & Society, 25(3), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00267.x

Rose, G. (2022). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (Fifth edition). Sage Publications.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pjjh

Rosenstein, B. (2002). Video Use in Social Science Research and Program Evaluation. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(3), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100302

Rutanen, N., Amorim, K. de S., Marwick, H., & White, J. (2018). Tensions and challenges concerning ethics on video research with young children—Experiences from an international collaboration among seven countries. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 3(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-018-0019-x

Schulenkorf, N., Edwards, D., & Hergesell, A. (2020). Guiding qualitative inquiry in sport-for-development: The sport in development settings (SPIDS) research framework. Journal of Sport for Development, 8(14), 53–69. https://jsfd.org/2020/05/01/guiding-qualitative-inquiry-in-sport-for-development-the-sport-in-development-settings-spids-research-framework/

Schulenkorf, N., Sherry, E., & Rowe, K. (2016). Sport for Development: An Integrated Literature Review. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0263

Shaw, M. P., Satchell, L. P., Thompson, S., Harper, E. T., Balsalobre-Fernández, C., & Peart, D. J. (2021). Smartphone and Tablet Software Apps to Collect Data in Sport and Exercise Settings: Cross-sectional International Survey. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(5). https://doi.org/10.2196/21763

Sleijpen, M., Boeije, H. R., Kleber, R. J., & Mooren, T. (2016). Between power and powerlessness: A meta-ethnography of sources of resilience in young refugees. Ethnicity & Health, 21(2), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2015.1044946

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Sobotová, L., Šafaříková, S., & González Martínez, M. A. (2016). Sport as a tool for development and peace: Tackling insecurity and violence in the urban settlement Cazucá, Soacha, Colombia. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(5), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1214616

Søndergaard, E., & Reventlow, S. (2019). Drawing as a Facilitating Approach When Conducting Research Among Children. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918822558

Sport for Development Coalition. (2015). Sport for Development: Outcomes and Measurement Framework. https://sportfordevelopmentcoalition.org/sites/default/files/user/SfD%20Outcomes%20and%20Measurement%20Framework.pdf

Strachan, L., & Davies, K. (2015). Click! Using photo elicitation to explore youth experiences and positive youth development in sport. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(2), 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2013.867410

Tol, W. A., Barbui, C., Galappatti, A., Silove, D., Betancourt, T. S., Souza, R., Golaz, A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2011). Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: Linking practice and research. The Lancet, 378(9802), 1581–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61094-5

United Nations. (2021). SDP Toolkit Module: Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E). United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://social.desa.un.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/SDP%20Module%20Monitoring%20%20Evaluation%20Final.pdf

van Ingen, C. (2016). Getting lost as a way of knowing: The art of boxing within Shape Your Life. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(5), 472–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1211170

Volpe, R. J., DiPerna, J. C., Hintze, J. M., & Shapiro, E. S. (2005). Observing Students in Classroom Settings: A Review of Seven Coding Schemes. School Psychology Review, 34(4), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2005.12088009

Water, T., Payam, S., Tokolahi, E., Reay, S., & Wrapson, J. (2020). Ethical and practical challenges of conducting art-based research with children/young people in the public space of a children’s outpatient department. Journal of Child Health Care, 24(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518807318

Westbrook, J. I., & Woods, A. (2009). Development and testing of an observational method for detecting medication administration errors using information technology. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 146, 429–433. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-60750-024-7-429Whitehead, J., MacCallum, L., & Talbot, M. (2012). Designed to move: A physical activity action agenda. The Commonwealth. https://www.sportsthinktank.com/uploads/designed-to-move-full-report-13.pdf

Whitley, M. A., Coble, C., & Jewell, G. S. (2016). Evaluation of a sport-based youth development programme for refugees. Leisure/Loisir, 40(2), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2016.1219966

Whitley, M. A., Fraser, A., Dudfield, O., Yarrow, P., & Van der Merwe, N. (2020). Insights on the funding landscape for monitoring, evaluation, and research in sport for development. Journal of Sport for Development, 8(14), 21–35. https://jsfd.org/2020/03/01/insights-on-the-funding-landscape-for-monitoring-evaluation-and-research-in-sport-for-development/