Anna Farello1 & Holly Collison-Randall1

1 Loughborough University London, UK

Citation:

Farello, A. & Collison-Randall, H. (2023). A contemporary perspective on the traditional gap between ‘clean minds’ and ‘dirty hands’ in the sport and refugee movement. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Sport for Development (SfD) literature tends to focus on and value bottom-up, grassroots projects and realities, and criticize top-down (i.e., from high- to low-authority) approaches. This is also true when considering the intersection of sport and refugees. With millions of people displaced every year, a new perspective is needed to reconcile bottom-up and top-down approaches. In this conceptual paper, we provide literature that frames traditional and contemporary issues embedded in the refugee and sport domains with a specific focus on the top-down, bottom-up approaches SfD stakeholders adopt. From these stakeholder configurations, associated challenges, and complexities, we present a contemporary effort to challenge the ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ dichotomy; namely, by drawing parallels to the concept of clean minds (top) and dirty hands (bottom). We interrogate this discrepancy in two ways: first, through our experiences and interpretations as members of the Olympic Refuge Foundation’s Think Tank; second, by merging the “clean minds, dirty hands” concept with Lefebvre’s (1991) theory of social space. Ultimately, the clean minds, dirty hands dichotomy is better represented as a spectrum that interacts with Lefebvre’s theory in unique ways. Implications for influencing the sport and refugee movement, as well as the broader field of SfD, are discussed.

A CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE ON THE TRADITIONAL GAP BETWEEN ‘CLEAN MINDS’ AND ‘DIRTY HANDS’ IN THE SPORT AND REFUGEE MOVEMENT

The field of Sport for Development (SfD) focuses on achieving wider social outcomes through sport such as social inclusion, economic development, public health, and conflict resolution (Lyras & Welty-Peachey, 2011), as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations, 2015). In the last ten years, global circumstances forcing people to flee their homes have offered SfD a unique opportunity to engage with refugee contexts. Such opportunities exist in refugee camps and in host countries, where refugees ultimately attempt to seek asylum and resettle. Turkey, Colombia, and Germany each host over 2 million refugees, and Lebanon hosts the most refugees per capita (one refugee for every four nationals) (UNHCR, 2021a). In 2022, the number of displaced people around the world reached an unprecedented high of over 100 million. Many host countries are thus experiencing an influx of refugees, stemming from both ongoing and more immediate unrest. The Syrian political crisis, for instance, has caused thousands of citizens to relocate to Turkey, Jordan and Palestine since 2015 (UNHCR, 2021b), and the recent Russian invasions of Ukraine have forced millions to seek safety across Europe. People in power (e.g., policymakers, extreme political groups) and media outlets have created a negative rhetoric around refugee populations (Philo et al., 2013), leaving them marginalized and misunderstood. Metaphors have been used in print and in speech to reference people seeking refuge en masse, such as waves, swarms, and invasions, all of which are portrayed as large-scale problems in need of control (Serafis et al., 2019).

It is best practice, however, in the field of SfD to take a humanizing approach towards those who have been forced to migrate (Cárdenas, 2013), viewing and treating them as valuable individuals, ones who have assets and strengths that can contribute to the broader community in which they resettle (Ryu & Tuvilla, 2018; Spaaij et al., 2019; Weng & Lee, 2015). Further, research has shown refugees to be civic-minded, wanting to engage with their host communities (Weng & Lee, 2015), as well as hopeful and resilient despite the challenges and adversity they face (Keles et al., 2018; Ryu & Tuvilla, 2018). With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, a UN survey found that Ukrainian refugees “want to play a more active role in their new communities, but need support such as language classes, formal recognition of skills, and, importantly, assistance with childcare services” (UN News, 2022). Others note that due to the increase in work-age individuals in Europe, the labor market would significantly increase in countries proximal to Ukraine (e.g., Czech Republic, Poland) and host countries’ economies would be boosted by additional people in the workforce (Bahar et al., 2022; Dumont & Lauren, 2022).

Nonetheless, constant small changes in political situations across the world—in both host and origin countries—make for a refugee context that is too complex and dynamic for SfD to address on its own. The field needs innovative solutions that allow sectors to collaborate and create new knowledge (i.e., transdisciplinarity) (Whitley et al., 2022), as well as innovative perspectives on traditional and contemporary issues. This paper thus contributes to the SfD field by (1) critically reconfiguring Makhoul et al.’s (2013) ‘clean mind, dirty hands’ concept using the Olympic Refuge Foundation’s Think Tank as an example of innovation in the sport and refugee movement, (2) confronting the current dichotomous nature of the ‘top’ (clean minds) and ‘bottom’ (dirty hands), and (3) offering an analysis of the Think Tank using Lefebvre’s (1991) theory of social space. SfD scholars have yet to analogize the top and bottom as clean minds and dirty hands, and Lefebvrian theory is infrequently utilized in the sport domain (cf. Marchesseault, 2016). We argue the following: the clean minds at the top and dirty hands at the bottom do not have to be dichotomous or mutually exclusive; in its best form, the two constantly inform one another in the overlapping spaces amongst thought, production and action. Importantly, it must be recognized and dispelled that associating the terms ‘top-down’ with ‘clean minds,’ and ‘bottom-up’ with ‘dirty hands’ may improperly assign moral notions of ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ respectively. It is the authors’ intention with this paper, rather, to neutralize these connotations and offer a new way of thinking about how SfD interacts with these terms and the individuals and organizations that are associated with them.

This manuscript follows what Jaakkola (2020) outlines as a “theory adaptation” approach to a conceptual paper. It “uses an established theory to explore new aspects of the domain theory” (p. 23). The adaptation put forth in this paper is meant to set the foundation for practitioners, scholars, and high-level authorities to rethink the way that the sport, refugee, and mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) sectors can harmonize and provide adequate care for refugee populations. We begin with a brief review of literature on the refugee context and what makes it unique, then move into SfD literature as it relates to the so-called top (clean minds) and bottom (dirty hands). We then discuss how Makhoul et al.’s (2013) clean mind, dirty hands concept works, in theory, and how Lefebvre’s understanding of social space works, in theory. The two come together in the final section and are applied to the inner workings of the ORF Think Tank.

Positionality

Both authors are women from high-resource countries, and are active members of the Olympic Refuge Foundation Think Tank. The first author has experience conducting research with (former) refugees, and the second author is a world-leading anthropologist in SfD. The second author invited the first into the Think Tank to conduct research for her PhD. It was the first author’s engagement with the Think Tank that forms the basis of this paper.

The Unique Refugee Context

We recognise that the term ‘refugee’ is sometimes defined as one who has successfully applied for and been granted asylum in a country different from their own. For the purpose of this paper, we define a refugee as one who has been forced to flee their home country and seek safety in another, due to war, violence, conflict or persecution (UNHCR, 2021c). While refugee populations are often grouped into conversations and debates about broader marginalized groups, the refugee context is entirely unique. Literature on the refugee sector points to two common contributors to this uniqueness: liminality and resilience. It is the combination of these factors that separates the refugee context from other contemporary issues and makes it an intriguing avenue for the SfD field to pursue.

For those in the process of finding refuge, home is impermanent, which leaves refugees in limbo, or a state of liminality (van Gennep, 1960). The majority of refugees who have fled to a different country to apply for asylum are at risk of being denied refuge and sent away (UNHCR, 2021a, Hartonen et al., 2022), which exposes an additional layer of liminality compared to when they were en route. In other words, refugee groups are in a physical liminal space between two countries, as well as a figurative liminal space of being awarded or rejected the human right to seek asylum (Hartonen et al., 2022). While liminality engenders uncertainty and a lack of security for refugees, there is the additional element of not knowing when liminality will end (uncertainty within uncertainty) (Benezer & Zetter, 2015; Hartonen et al., 2022). The fact that refugees are frequently in transit and in tenuous circumstances makes them unique compared to other types of migrants who may have more agency and control over their circumstances.

The other common element in refugee literature that contributes to the context’s uniqueness is resilience. An increasing breadth of research in the past decade has found that hope and resilience are hallmarks of a refugee’s experience, despite the liminality and trauma they may have endured before, during, and after their journey (Keles et al., 2018; Pieloch et al., 2016; Rivera et al., 2016; Sleijpen et al., 2016). Resilience has been shown to be a skill one learns and practices, rather than a trait that is either possessed or lacked (Rivera et al., 2016), suggesting anyone, or any refugee, can become resilient and enhance it. According to Sleijpen and colleagues (2016), factors that contribute to a young refugee’s resilience include social support, how one acculturates, education level, engagement with religion, and hope. The authors indicated that the promise of a better life compared to previous circumstances was an empowering tool for young refugees.

Physical activity can also help build resilience through relief and recovery from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Nilsson et al., 2019). Importantly, resilience and liminality are linked: gaining certainty in an aspect of one’s refugee journey, such as heritage and host cultures, or a favorable decision on an asylum application, is linked to resilience (Keles et al., 2018). There are, however, many instances in which refugees’ trauma leads to PTSD, depression, or another clinical mental health issue (Hadfield et al., 2017; Keles et al., 2018). Trying to escape war, torture, persecution, or imprisonment, in addition to experiencing family separation, bombings, property loss, and homelessness can have a lasting impact on a refugee’s mental health (Hadfield et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2016).

The unique refugee context is thus relevant to multiple disciplines (e.g., sport, mental health, psychosocial development), as refugee needs and concerns cut across the public, private, and third sectors. For example, in 2007 the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, a humanitarian group, coined the phrase mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS). MHPSS is used to “describe any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorder” (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, p. 16). The concept was defined and utilized by humanitarian aid organizations thereafter so that their responders were using a broad spectrum of support including mental, emotional, and physical health, for people in need such as refugees. MHPSS recognizes the specific holistic health needs of refugees on a profound level, which are unique to other types of migrants or marginalized groups. Like the refugee context, MHPSS is also connected to several disciplines, including but not limited to health, protection, psychology, and sociology/society, which have been woven into the refugee context in addition to the sport, exercise, and physical activity disciplines.

Looking at the unique aspects of the refugee context illuminates the fact that SfD is best structured to do what it intends: strive towards social and developmental outcomes through sport (Lyras & Welty Peachey, 2011), as opposed to comprehensively help people affected by displacement and address the unique aspects of their journeys. In other words, making an impact through quick responses to different crisis points is just beyond the boundaries of SfD because the field has a broader scope than those who have been forcibly displaced. Scholars in this field have continuously promoted the intentional and thoughtful planning of sport programmes, bespoke to local needs and conditions (Collison & Marchesseault, 2018; Dagkas et al., 2011; Giulianotti et al., 2019; Whitley and Welty Peachey, 2020), which is incompatible with the dire, fast-paced, and transient aspects of the refugee context. The humanitarian sector, on the other hand, is inherently mobile, includes rapid response mechanisms, and is thus better placed to address the immediate, survival-based needs of refugees (Beresford & Pettit, 2021); however, it lacks a sport-based component. Sport has yet to be fully embedded in the humanitarian sector (Cheung-Gaffney, 2018), but can address the holistic well-being of refugees where humanitarianism cannot. The siloed nature of sport from other disciplines is not a new issue, however. Academics in SfD have frequently called for deeper integration of, and connections across, different disciplines to help the field strive towards wider social outcomes such as the SDGs (Haudenhuyse et al., 2020; Whitley et al., 2022; United Nations, 2015). To reach for transdisciplinary harmony, however, sport scholars, practitioners, and policymakers must establish and nurture connections beyond the confinements of SfD.

The Sport and Refugee Movement

The sport and refugee sub-discipline of SfD has gained traction in the past several years (Spaaij et al., 2019) in response to the increase of displaced people globally and the wider recognition of the human rights shortcomings this population endures. For the purposes of this paper, this paralleled increase is one aspect of what the authors term ‘the sport and refugee movement’. The movement includes the surge of academic literature on sport and refugee populations, the expanding recognition by international and national organizations that sport is a viable mechanism for refugee populations to achieve well-being and social outcomes, and the growth of grassroots sport programs (and branches of extant programs) focusing on those who have been forcibly displaced. In naming the movement, we hope to inspire said programs and research to engage with and progress it. With that said, a growing number of sport programs and interventions have been established that focus on young refugees (e.g., Capalbo and Carlman, 2022; Doidge et al., 2020; Robinson et al., 2019), and specifically refugee girls and women (e.g., Luguetti et al., 2021; Mohammadi, 2019). Sport programs and interventions for refugees are often hosted in refugee camps (e.g., GIZ Sport for Development program in Kakuma Camp; Live Together program in Za’atari refugee camp) and community settings (e.g., Palestine Sports 4 Life in Ramallah; Soccer Without Borders in United States communities). Additionally, there are refugee-led SfD programs such as the Africa Youth Action Network (AYAN) and Corner65 that work towards development goals at the individual and community levels. Overall, there are many sport programs for refugees worldwide than academia may ever know about or study. Thus, the lack of knowledge and representation given by scholarly accounts is not reflective of the tremendous increase of sport-for-refugee sites and interventions. Although more knowledge about these programs is needed, the ones documented in academic literature are oriented towards social outcomes such as integration (e.g., Doidge et al., 2020), social inclusion (e.g., Block & Gibbs, 2017; Dukic et al., 2017), well-being (e.g., O’Donnell et al., 2020), and/or employment (e.g., Pink et al., 2020) of young refugee populations, but evidence of their effectiveness is mixed (Spaaij et al., 2019). In this way, scholarship on the sport and refugee movement will inevitably lag behind the pace of SfD program creation worldwide.

An additional issue within the sport and refugee movement is that it is inherently slow to react to the ever-changing refugee landscape; this is because addressing refugee dilemmas and evolving crises as they arise requires structure and customization from SfD, a combination it slightly lacks. In other words, SfD’s focus on developing, managing, monitoring and evaluating programs takes time, when political climates can elicit shifts in the refugee context in a matter of days. These points illustrate that the refugee context suffers from the same limitations and structural complexities that other SfD sub-disciplines and the broader development sector have experienced; in particular, the age-old dilemma of top-down versus bottom-up interactions, participant engagement, and measured impact. The sport and refugee movement is still largely dominated by entities and countries considered to be at the ‘top’. For example, Western European countries, the United States, and Australia are the largest contributors to research on the sport and refugee movement (Spaaij et al., 2019). Others at the top, by Black’s (2017, p. 9) definition include “national, inter-governmental and corporate development actors” that have power and influence over what happens on the ground. With this in mind, we provide the following question to guide our account of the refugee and SfD sub field: How should initiatives in the sport and refugee movement be approached (e.g., top-down, bottom-up, a combination of both) to achieve or strive towards wider social outcomes? We propose that the sector needs a new way of conceptualizing and managing top-down and bottom-up relationships and tensions.

Top-Down, Bottom-Up Tensions in SfD

Scholarship on what top-down versus bottom-up approaches entail is generally stable. Whitley and colleagues (2021) concisely define top-down as “governmental support” (p. 10), and use inside-up, or locally owned, as another phrase for bottom-up. An additional type of effort they offer is outside-in, which signifies externally supported approaches. Here, the scope of this paper narrows to top-down and bottom-up (or inside-up) efforts. In SfD, much of its academic attention has inherently focused on development at the local, grassroots level and the impacts of interventions on target populations (bottom-up). The discipline has confronted internal scrutiny about its Western skewed composition and neo-colonial efforts in low- and middle-income countries (Darnell & Hayhurst, 2011; Hartmann & Kwauk, 2011; Welty Peachey et al., 2018), which has reinforced a desire to be inclusive, youth-oriented, and up-close-and-personal to tangible change. Scholars and practitioners alike thus seem to have developed an affinity towards local, community-bred organizations (Garamvölgyi et al., 2022; Whitley & Johnson, 2015), which has distanced actors who work on the broader, higher levels, such as policymakers. Such top-level individuals and organizations of international authority have been known to perpetuate and condone neo-liberal and neo-colonial policies that impact the grassroots level; it might be suggested that the top ‘contaminate’ otherwise ‘clean-minded’ sports programs. As a result, SfD scholars typically illuminate the work of those who are getting their hands dirty and doing work on the ground with often-marginalized people. The knowledge generated at this level is invaluable to the field, compelling to those researching broader aspects of SfD, and of interest to practitioners and actors striving towards the SDGs. Seeing the world through the lens of those at the ‘bottom’ gives insight credibility and acts as a rite of passage (van Gennep, 1960) for scholars in the discipline.

Currently, in SfD there are limited mechanisms in place that bridge ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches, though scholars have discussed the downsides of the top-down approach of sport interventions and policy (Black et al., 2017; Darnell, 2014; Garamvölgyi et al., 2022; Whitley & Johnson, 2015). Sport programs are rarely created with the intention of having a majority top-down or bottom-up flow of information, but typically the top-down approach dominates, leaving youth participants with lived experience in a position of little to no authority. This is especially true for refugee populations who are often considered vulnerable or less capable (Edge et al., 2014; Parrott et al., 2019).

Top-down approaches can be slow to provide physical and mental health services to refugee groups because of extensive protocols and legal hoops to jump through; perhaps more importantly, they do not always provide what is actually needed by those on the ground (Kang & Svensson, 2019; Lyras & Welty-Peachey, 2011; Rosso & McGrath, 2016; Thorpe & Ahmad, 2015). As Thorpe (2016, p. 105) explained: “care must be taken to avoid top-down approaches that prioritize the interests of stakeholders over the needs, experiences and voices of local residents”.

Bottom-up approaches, on the other hand, can suffer from a lack of resources or pathways to appropriately address their needs (Black et al., 2017). With that said, those immersed in a specific context know their context best. Often, community-based organizations are the best placed groups to conduct an intervention. Whitley and Welty Peachey (2020) talked about pushing SfD programs forward through place-based accelerators, or small-scale programs that train local staff to run culturally sensitive, community-based sports. They suggested that training come from NGOs rather than from the ‘top’. For people such as young refugees who are an often-marginalized group with specific needs, their perspectives and needs should be at the forefront of SfD initiatives. Recently, more co-creation studies are being conducted, which involve refugees as equal partners in program planning (Luguetti et al., 2021; Luguetti et al., 2022; Robinson et al., 2019; Simonsen & Ryom, 2021). While this is best practice for working with marginalized groups, it is not yet the norm for interventions in SfD. Even though top-down and bottom-up approaches in SfD should be, and are said to be, symbiotic, “it is also, very obviously, an unequal symbiosis, with top-down actors and interests routinely predominating” (Black et al., 2017, p. 14). It has thus been asserted that a combination of top-down and bottom-up tactics are needed to be the most effective in meeting program goals and working towards the SDGs (Kang & Svensson, 2019; Lyras & Welty Peachey, 2011).

In academia, top-down and bottom-up approaches have been managed by different scholars across disciplines. In the ‘top’ realm, such as policy, Iain Lindsey has written on policy coherence and the SDGs (see Lindsey & Darby, 2019), while Oliver Dudfield contributed to the Kazan Action Plan, an agenda that reconstructs previous sport policy so it now inherently aligns with the SDGs (see UNESCO, 2017). Contrarily, the discipline of anthropology has addressed the ‘bottom’ realm, with scholars such as Holly Collison-Randall and Cora Burnett focusing on the local level (see Burnett, 2015; Collison et al., 2017). In sociology, there is a combination of literature catering to the meso- and bottom levels, with scholars like Richard Giulianotti researching the middle ground between local populations and higher authorities (see Giulianotti et al., 2016), and Ramón Spaaij often publishing empirical work from the ground (see Spaaij & Schailleé, 2020).

Despite the disciplines in which SfD experts reside, the same gap between the top-down and bottom-up approaches exists. As Black (2017, p. 8) pointed out, however, “The challenge faced by scholars and practitioners is not the lack of connections, but rather the form and effects of these connections.” It is thus time for an innovative way of establishing and maintaining connections that revolutionize the dichotomous top-down or bottom-up approach.

Innovation in the Sport and Refugee Movement

As can be seen in the increase in co-creation interventions with refugee populations, SfD as a sector is growing significantly in terms of innovation. Also indicative of such trends in novel thought are disciplinary connections beyond SfD, such as psychosocial support (Ley & Barrio, 2019), pedagogy (see Luguetti et al., 2021; Luguetti et al., 2022), and ethics (Cain & Trussel, 2019), amongst others. Outside of academia, the sport and refugee movement is burgeoning as well. For one, elite sport invested in refugees with the inaugural Refugee Teams competing in the 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, which intends to be sustained for future Games. Further, an all-refugee women’s football team from Kakuma refugee camp now plays in the Kenya National League (sportanddev.org, n.d.). Professional sports clubs have also opened their teams to refugee players and celebrated their membership (e.g., footballers Nadia Nadim and Alphonso Davies; swimmer Yusra Mardini; former basketballer Luol Deng), and youth sports programs are becoming more inclusive for young refugees (e.g., African Youth Action Network; Brighton Table Tennis Club; LACES; Soccer without Borders).

Innovation is also happening at the policy level, with initiatives such as the Kazan Action Plan being implemented (see UNESCO, 2017). Each of these examples presents a new way of thinking that extends sport’s reach to different sectors and experts in the sport and refugee movement. The final innovative contribution to the movement comes from the Olympic Refuge Foundation (ORF), which was created in the wake of the 2016 Olympics and has created sport programs worldwide for young people affected by displacement. It also has three branches, or extensions, including the Sport for Refugees Coalition, a Community of Practice, and a Think Tank, the latter on which our scope narrows for this paper.

The Olympic Refuge Foundation Think Tank

In early 2020, the ORF established a Think Tank of 26 experts in the domains of sport, refugees, and MHPSS. The Think Tank’s main aim is to support the ORF’s worldwide sport programming by providing and strengthening the evidence base of sport’s utility as a humanitarian mechanism for the holistic well-being of young people affected by displacement. The Think Tank is an extension—rather than part of—the ORF, which sits under the umbrella of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The Think Tank meets virtually each month and is organized into three working groups including Guidance and Tools, Research and Evaluation, and Advocacy and Thought Leadership. The Guidance and Tools group focuses on identifying and collating best practices for sport programs for refugee and displaced young people. The Research and Evaluation group identifies and attempts to close gaps in the literature on the nexus of sport, refugees, and MHPSS. The Advocacy and Thought Leadership group is more outward facing, and considers how other individuals and organizations can potentially learn or gain from the inner workings of the Think Tank. Within the virtual Think Tank space, every member’s extant knowledge, thoughts, and values merge, everyone is able to learn from one another, and steps are taken to further strengthen the literature on the intersection of sport, refugees, and MHPSS. Despite the tension between the top-down and bottom-up ends of the spectrum, we admit there is merit in the experiences and journeys of those at the top. In this paper, we spotlight a high-level Think Tank replete with experts in the areas of sport, refugees, and MHPSS.

Clean Mind, Dirty Hands: The Concept, In Theory

One way of conceptualizing this notion of the top and bottom in SfD is through Makhoul et al.’s (2013) concept of ‘clean mind, dirty hands’. In 2013, Makhoul and colleagues led a community participatory action research study that applied the concept of “clean mind, dirty hands”, or in its original Latin, “manus sordidae, mens pura” (Coggon et al., 1997, as cited in Makhoul et al., 2013). According to the authors, the clean mind represents a researcher’s effort to conduct academically rigorous work, while the dirty hands represent the practical side of research, where theory is put into practice, which can be challenging and messy. In any practical fieldwork endeavor, the duality of this concept can be experienced on a profound level. Within SfD particularly, grassroots work—or the dirty hands side—is highly encouraged and praised in the academic community, and it is generally believed that the ‘doers’ are on the ground. Scholars in this field have a proclivity to work with non-governmental organizations (NGOs; e.g., Giulianotti), and marginalized populations in grassroots settings (e.g., Spaaij, Collison) as they are often inclusive by nature and may have limited resources to collaborate or conduct their own research. Conversely, in SfD there seems to be a general dislike or aversion to powerful policymakers and business moguls, perhaps because their decisions can have negative trickle-down effects on grassroots programs. Further, the fact that they are less accessible to those at the community level might make them more mysterious and intimidating. While people at the top represent the ‘clean mind’ in this analogy, there are different ways of applying Makhoul’s concept.

The ‘clean mind, dirty hands’ concept can be applied in different ways, for instance, by viewing the grassroots organizations as having the clean minds in that they are morally and ethically inclined to provide positive sport experiences for young people. Those at the top, on the contrary, could have dirty hands in the sense that they do not seem to consider the implications of their policies and decisions. Nicholson (2010) offers another interpretation of this concept, stating a ‘clean mind’ is used to “judge the evidence” that those with dirty hands brought from collecting data. Additionally, in the literature we see that honest accounts of research projects expose the expectations of the fieldwork and the reality of the specific situation. In Makhoul et al.’s (2013) study, for instance, they discuss how they involved a Palestinian refugee camp community in creating a mental health program for young people. While their clean mind theoretically involved community members in all stages of the research process, the result was that “real-life conditions of the camp and its residents, youth and adults alike, stood in the way of rigorous participatory research” (p. 515). Similarly, Amara and colleagues (2005) found that policies relating to sport as a mechanism for the social inclusion of young refugees could be difficult to implement: “While policy outputs may signpost good practice, the reality ‘on the ground’ may be somewhat different” (p. 28). In this case, the policy acts as the clean mind rather than academic rigour in Makhoul et al.’s study.

The lack of consensus on how Makhoul et al.’s concept could be applied makes room for innovative interpretations and applications. Thus, for the purposes of this paper, clean minds refer to individuals and organizations at the top; that is, international program directors, policymakers, or Executive Directors of NGOs. Conversely, dirty hands refer to people with lived experience of forced displacement, as well as practitioners who work with people who have been forcibly displaced. The Think Tank contains individuals who are predominantly, but not completely, aligned with clean minds compared to dirty hands. It is therefore crucial to note that there is ambiguity around how those with both clean minds and dirty hands are considered; some individuals and organizations do not clearly fit into either category. It is also the case that the degree to which one identifies with a clean mind or dirty hands may change, depending on the circumstances. The rest of this paper is dedicated to explicating the nuances and complexities of the unexplored ‘dichotomy’ of clean minds and dirty hands in SfD.

Lefebvre and Social Space: In Theory

Henri Lefebvre was a French philosopher whose work crossed over into social science and geography, hence the ‘social’ production of space. He spoke at length on capitalism and the economy in general, but this is less related to the Think Tank. Though a Marxist at heart, scholars have compared his work to the likes of his contemporaries, including Sartre, Althusser, and Foucault, amongst others (Stewart, 1995). Lefebvre opposed structuralism and existentialism, and was a humanist who saw space as simultaneously concrete and abstract (Fuchs, 2019). Though he was less commonly known compared to other philosophers alive at his time, Lefebvre’s La Production de l’Espace (1991) is thought provoking work on which our analysis is based.

The Lefebvrian Perspective

Lefebvre saw space in extraordinary ways. For instance, he theorized that at the core of space are humans; we are both its creators and by-products. By this he meant humans create space physically, and the space or environment in which we grow up plays a critical role in making us who we are—space produces us. In a broader sense, societies are constructed from space, and “every society…produces its own space” (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 31). The result is a site where abstract creations can become reality (Karplus & Meir, 2013). Stanek (2007, p. 75) calls this process “becoming true in practice,” which means that space is “produced by material, political, theoretical, cultural, and quotidian practices”. These sites are linked in a relational, rather than linear, way, thus embodying the ‘social’ aspect of Lefebvre’s social space. As humans create, are created by, and relate to one another in space, Lefebvre sees space as dynamic and active (Kohe & Collison, 2020), rather than stagnant, as some of his contemporaries saw it. We see his viewpoint on space as akin to Coakley’s on sport (2011); he called sport an empty signifier, that it only had as much meaning as humans ascribed to it.

Something we struggled with while applying this theory of space is whether it was concrete or abstract. But in fact, it is both! Gottdiener (1993, p. 130) explains this duality succinctly:

Space was a concrete abstraction. That is, space was both a material product of social relations (the concrete) and a manifestation of relations, a relation itself (the abstract). It was as much a part of social relations as was time.

Again, we can see how human interactions create and influence space. Put another way, “space is a mental and material construct” (Elden, 2007, p. 110). While space can have tangible or material properties such as four walls, its abstract or mental properties would be how the people within those four walls relate to one another. In short, it’s impossible to truly capture and define space. Like a cloud in the sky, sometimes we can pinpoint where it starts and ends, but other times it is more difficult. Clouds, like space, are always moving and shape-shifting depending on environmental or external factors. For clouds, these might include wind, temperature, pressure, and humidity. For space these factors might include the characteristics of the people who are creating the space, and societal norms, for instance. Said another way, space can be better understood if we can genuinely grasp the cultural, geographic, temporal, and social components of a space (Kohe & Collison, 2020). Lefebvre saw how various aspects of one’s life (e.g., physical, mental, social) could harmonize with and in one’s surroundings (Elden, 2007); his ideals certainly align with the holistic approach of SfD.

Lefebvre (1991) conceptualized social space into three components: representations of space, spatial practice, and representational spaces. Some scholars have used alternative names such as thought / conceived space, production / perceived space, and action / lived space, respectively. Speaking in terms of thought, production and action is more germane and understandable for the purpose of this article, so these will be used hereafter. In brief, the thought space is a ‘pre-condition’ for production and action, where a group’s experiences, thoughts, and knowledge come together. The production space—which in this case is the Think Tank itself—is comprised of social relationships and physical (or here, virtual) space. Finally, the action space is where life happens, where topics can be debated, dismantled, and reconstructed. These three dynamic spaces of Lefebvre’s theory are interconnected, interdependent and holistically comprise the social space. In the next section, each part of the triad will be explained, as well as how each is analogous to the Think Tank and Makhoul et al.’s (2013) concept of clean mind, dirty hands.

Lefebvre and Clean Mind, Dirty Hands: In Practice

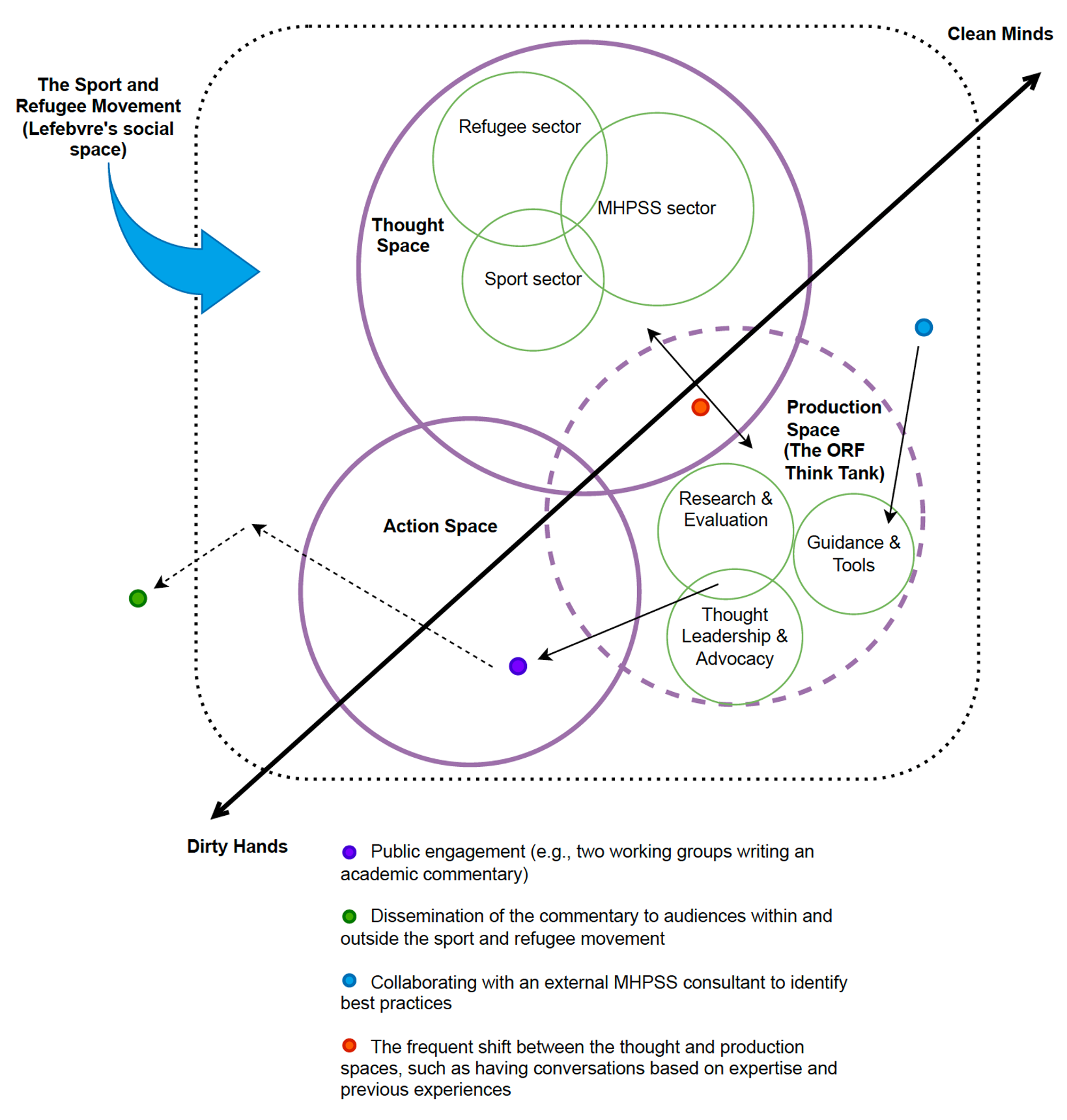

This section clarifies how the three components of social space (i.e., thought, production, and action spaces) interact with the clean mind, dirty hands concept and the ORF Think Tank. These comprise what Lefebvre calls the ‘social space,’ which in this case we refer to as ‘the sport and refugee movement’. We show how Lefebvre and Makhoul et al.’s concepts come together in a practical, more tangible way by applying them to the ORF Think Tank. Figure 1 below offers a visual of the interaction between these concepts in the Think Tank.

Thought Space / Representations of Space

Although the conceptual triad of thought, production and action does not function linearly, the thought space is like a basis or precondition for the production and action spaces. According to Hayday et al. (2020), the thought space is “a metaphysical starting point for understanding spatial construction” (p. 3). This is where knowledge and power come together in a constructive manner, including individuals’ shared values and interests, points of understanding, and morality and ethics. There is therefore an abstract thought space for any entity, group, or discipline. An SfD organizational thought space, for instance, would be inclusive of a variety of perspectives, beliefs, and backgrounds within the discipline. In the case of the Think Tank, the thought space is exclusive to invited members and thus, purposive, based on members’ backgrounds. Thus, the multidisciplinary origin of the Think Tank is where people from various backgrounds, nationalities, and careers come together using their expertise. The thought space is the intersection of sport, displaced populations, and MHPSS that brought all 26 members to the Think Tank to work towards progress in the sport and refugee movement. Consequently, there are individuals who have expertise in any of these three areas, but are not Think Tank members due to its confinements.

Another aspect of thought spaces is that they are “not only socially constructed, but they are representations of power and ideology, of control and surveillance. They are the ‘ideal’ of how society should be” (Marfell, 2019, p. 594). This is a direct link to Makhoul et al.’s (2013) clean mind, which concerns itself with theory and how, in their case, research should be used and conducted. Both clean minds and the thought space impose order and expectations, as well as imagination, or “imagined space” (Elden, 2007, p. 110, emphasis in original). The thought space is where the Think Tank and clean minds can visualize a future based off of success in their field and the potential impact their work can make; it is where we can think, plan, theorize, and create (Elden, 2007). We note, however, that a clean mind is not comprehensively synonymous with the thought space. In fact, as mentioned above, our conceptualization of clean minds is different from that of Makhoul et al. (2013). With a clean mind representing those at the ‘top’ of SfD and the sport and refugee movement, it mainly overlaps with the thought space in that both are symbols of power and what could be. Beyond this, we invite future research to build upon the foundations set out in this paper.

Production Space / Spatial Practice

While the thought space is representative of the brain-based work of the Think Tank, the production space is akin to the Think Tank itself. The production space is a physical form, a site that is generated and used. This is a unique aspect with the Think Tank as its international members and intersection with the global pandemic meant it exists in a virtual production space. Also called ‘perceived space’ by Lefebvre, this space includes the behaviors, dispositions, and overt interactions of people, in this case, the Think Tank members, within the space (van Ingen, 2003). The social relationships, formalities, and potential hierarchies that exist in the group are thus perceivable, and part of the production space.

In addition to the social relationships within the Think Tank, the Think Tank as a whole has relationships with other entities which count as part of the production space: its existence as an extension of the Olympic Refuge Foundation, its connection to the International Olympic Committee, the Sport for Refugees Coalition, Community of Practice, the Commonwealth Secretariat, and more. Lefebvre notes that this space works best when these social relationships—in and out of the Think Tank—are cohesive. The harmony of the relationships is what makes the space one of production.

However, we believe there is significant value in the process of getting to that place of harmony or cohesion. In other words, the contestations, discussions, and meticulously planned projects are part of the production space as well. In one sense, this is the clean-minded Think Tank shifting to a more dirty hands orientation. For instance, the authors collaborated with another Think Tank member on a small, internal project which took months of planning, analyzing, gathering feedback, and publishing. Thus, both clean minds and dirty hands can have a seat at the table in the Think Tank production space, but no individual, nor the Think Tank itself, is always aligned with either a clean mind or dirty hands. Rather, a spectrum of clean minds (top) to dirty hands (bottom) exists, challenging the traditional dichotomy.

Action Space / Representational Space

Lefebvre’s final space is the representational, or action, space. This space lends itself perfectly to ‘dirty hands’ (Makhoul et al., 2013), as it is largely based on how we can bring thought and production together to create action. Also called the lived space, it is “shaped by the symbolism and meaning vested in space by society. It can be seen as the emotional bonding agent between society and its space, a produced ideology of space and sense of place” (Karplus & Meir, 2013, p. 26). In a given society, group, or in this case, Think Tank, the action space will look differently, with informal or local forms of knowledge (Elden, 2007) forming the vital basis for action to occur. Similar to how Elden referred to the thought space as ‘imagined,’ he refers to the action space as ‘real’. This realness, this reality, is exactly how Makhoul and colleagues (2013) define dirty hands. They represent what truly happens in research, what happens at the ‘bottom,’ despite our ‘clean mind’ effort to collect data smoothly.

Simply put, the action space, and dirty hands, are messy. Hayday et al. (2020) discussed this third space as a site for advocacy and activism, for “challenging power relations, disrupting structural hierarchies and rebuilding democratic conditions for spatial membership” (p. 4). While the production space houses any potential power structures that exist, the action space is where it can be eliminated or reinforced. The critical thought that goes into the action space, the lived space, can pave a path for new ways of thinking, producing, and even acting (Kohe & Collison, 2020). Similar to how the thought space is not exclusive to clean minds, the action space is not exclusive to dirty hands; the movement between the spaces by those with clean mind or dirty hands orientations is what warranted the creation of a spectrum to counter dichotomous thinking. The culmination of the clean minds, dirty hands concept and Lefebvre’s theory of social space are presented in Figure 1 below.

Lefebvre and Clean Mind, Dirty Hands: A Visualization

Figure 1 is a visual of how we conceptualize and interpret Lefebvre’s theory of social space in regard to the status quo of the ORF Think Tank in 2022. The dotted outer boundary represents Lefebvre’s social space, which in this case is representative of the sport and refugee movement. As discussed, the thought space is the foundational precondition filled with Think Tank members’ expertise, values, and previous experiences. It contains the three sectoral backgrounds in which members are experts. The Think Tank itself comprises the production space, which inherently contains social relationships, networks and hierarchies within the group. The thought and production spaces significantly overlap because the production space is dependent upon the thought space; without Think Tank members’ values, beliefs, experiences, and thoughts, the entity would not exist. Though the action space was quite siloed from the thought and production spaces early on in the Think Tank’s tenure, in 2022 it is more integrated, and thus overlaps with the other two spaces.

Figure 1 – Lefebvre and Clean Mind, Dirty Hands: A Visualization

A Conceptualisation of Lefebvre’s Theory of Social Space as Applied to the formation of the ORF Think Tank. The clean minds, dirty hands spectrum runs through all three spaces, with dirty hands being most closely associated with the action space.

Within the three spaces, there are siloes and overlaps as well. In the thought space, for instance, Figure 1 shows the sport sector barely overlapping with the MHPSS and refugee sectors; at the Think Tank’s inception, sport was more disconnected from them. This represents a shift in discourse from heavily MHPSS and refugee focused to a more balanced focus that includes sport. Similarly, in the production space there is overlap—in this case, collaboration—between the thought leadership and research sub-groups, which was non-existent a year earlier. The guidance and tools group was interpreted to be more disconnected with the other two sub-groups.

In addition, Figure 1 presents four key moments in the Think Tank’s tenure that align with different spaces. The creation and dissemination of an academic commentary, for example, is a project that started in the production space, moved through the action space and extended beyond it, exemplifying that action occurs beyond the confinements of the group as a result of in-group discussions and learning. The arrows emanating from the production space, through the action space and beyond, are representative of the potential of Think Tank work to move into the broader refugee and sport movement, as well as beyond it. Finally, the bi-directional arrows between the thought and production spaces demonstrate a cycle of discussion about certain topics. Members seem to frequently connect their values, beliefs, expertise and thoughts to what they say and propose during monthly meetings. This reflects a merging of the two spaces that was less apparent in the Think Tank’s early days.

The other crucial component of Figure 1 is the thick arrow running through all three spaces; this is the clean minds, dirty hands spectrum. Throughout this paper, we have mentioned that the thought space and clean minds were not completely synonymous but had shared traits, as well as the heavy similarities between dirty hands and the action space. And, the production space is where those with clean minds and dirty hands come together. The spectrum allows SfD scholars, practitioners, directors, and policymakers to recognise that one may fall on any point of the spectrum depending on what a situation requires of them. For example, top-oriented, clean-mind officials may shift towards the dirty hands end of the spectrum if they thoroughly engage at the community level. In the same way, a practitioner with dirty hands may temporarily ‘wash their hands’ and shift towards the clean minds end of the spectrum if they are trying to influence government officials to enact better policy. No one and no organization thus has only a clean mind or only dirty hands; varying degrees of each can coexist, which the spectrum exemplifies. Finally, it is important to note that the spectrum purposefully extends beyond the sport and refugee movement, simply to establish the potential of the spectrum to be applied to other contexts, disciplines, and/or entities like the Think Tank.

DISCUSSION

So far in this manuscript we have laid out Lefebvre’s theory of social space and explained how it interacts with the clean mind, dirty hands concept in SfD. We challenge, however, that the latter concept is dichotomous. With Lefebvre’s theory being so dynamic, it would be unjust to ignore the thought that an individual—in this case, a member of the Think Tank—could have both a clean mind and dirty hands, doing work with those at both the top and the bottom. That said, it may not be feasible to have or embody both simultaneously. For Think Tank members who do work on the ground, this would imply that an internal process occurs where they change from the dirty hands side to the clean mind side before engaging with the Think Tank. They first ‘wash their hands’, or detach themselves slightly from their practical work, before having a clean mind. A benefit of going through this internal washing process is that it can minimize power dynamics within the Think Tank. However, by those with dirty hands getting clean and detaching from their work, those with clean minds can’t quite be aware of what tools and resources are needed on the ground, in the action space. Could those doing work on the ground bring their dirty hands into the clean mind space and be heard? Said another way, what happens when we move from the action space to the production space, instead of the (typical) other way around?

Ideally we are left with a cycle where clean minds inform dirty hands, and the results from getting one’s hands dirty then inform a clean mind. But we want to emphasize that a single individual can have varying degrees of both. In fact, we argue this is necessary for the field of SfD. Currently, it seems that those doing work on the ground mostly do just that. And those with clean minds at the top just stay there. The mixing of the two is rare, and when they do mix it can be laden with power imbalances skewed towards those with clean minds. But shifting the narrative, as the Think Tank is attempting to do, means abiding by a model where people with dirty hands have the opportunity to wash them and think with a clean mind, or simply come as they are. One way to concretize this mixing of clean mind and dirty hands is through the term “glocal,” coined by Giulianotti and Robertson (2004). Glocal is the connecting of global and local issues, and can thus be analogized to the merging of the global clean minds and local dirty hands. Garamvölgyi and colleagues (2022) claimed that social change can be achieved by complementing culturally-sensitive sport programs with top-down interventions at the grassroots level. In practice, this is what we would hope to see in the coming years in SfD. However, this would seem much more realistic if we were confident that those at the top had, at some point, dirty hands experience that informed their clean minds.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Both individuals and organizations, no matter where they identify on the spectrum of clean minds to dirty hands, can benefit from this novel conceptualization. Those doing work mostly on the ground can use this concept to recognise potential pathways to the top. By connecting with people who have a mixture of clean mind and dirty hands experience, for instance, a grassroots organization could then create a partnership or advocacy plan with people in the middle of the spectrum. In Lefebvrian verbiage, those heavily invested in the action space need to, temporarily, shift their focus and resources to the production space to have a greater impact at the top. On the other end of the spectrum, high-level organizations and individuals should look to organizations and individuals doing work on the ground to inform top-down policies and decisions. From the overlap of the production and action spaces, for instance, researchers could look to employ methodologies such as participatory action research, which involves doing research with, rather than on, a phenomenon. The thought and production spaces must be managed in such a way that the action space can properly overlap with each of them. Amplifying the voices of those doing work with refugees and internally displaced people will add crucial perspective to policies; the impact will then reach those who had input on said policies.

Given that many may find themselves somewhere in middle of the spectrum, having both a clean mind and dirty hands has its benefits and drawbacks. It means these individuals and organizations have the opportunity to be part of the link or bridge between those working on either end of the spectrum. As mentioned earlier, they can be the vessels through which information gets passed from the top down and from the bottom up. In addition, being in the middle means having the influence to effect more direct changes at either end. It is possible these individuals and organizations are more credible and influential because they have a broader range of experiences than those who stay at the spectrum’s ends. In a way, those who find themselves in the middle have the most dynamic shifting of spaces. They are more frequently moving amongst the action, production and thought spaces. A downside of this, however, is the likelihood of not being able to fully immerse oneself in any of the spaces—or either end the clean mind, dirty hands spectrum. With fixed amounts of time and resources, it may not be possible to get a comprehensive sense of what is happening at the top and the bottom. Nonetheless, there is great import for all individuals and organizations at any point on this spectrum, and in any of Lefebvre’s spaces. It is the communication and connections amongst the spectrum and the spaces that will determine how impactful SfD can be for young refugees.

Thus, the crux of this model demonstrates that space is not static and can be influenced and changed by the people within those spaces. Similarly, the dirty hands, clean mind concept is not at all dichotomous and should be treated and considered as a spectrum on which individuals and organizations can move. An essential implication of Lefebvre’s theory of space is that if change is to happen, the first order of business is to change the space. Only then should the pathways and next steps be pursued. The challenge, then, is ensuring that opportunities to connect and build bridges along the spectrum and within the three spaces are utilized to their full potential. What could the SfD sector look like if this were the case?

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there were no potential conflicts of interest in relation to this research.

REFERENCES

Amara, M., Aquilina, D., Argent, E., Betzer-Taya, M., Green, M., Henry, I., Coalter, F., & Taylor, J. (2005). The Roles of Sport and Education in the Social Inclusion of Asylum Seekers and Refugees: An Evaluation of Policy and Practice in the UK. Institute of Sport and Leisure Policy, Loughborough University, University of Stirling. pp 1-108.

Bahar, D., Parsons, C., & Vezine, P. L. (2022, March 17). Countries should seize the opportunity to take in Ukrainian refugees—it could transform their economies. Brookings.edu. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2022/03/17/countries-should-seize-the-opportunity-to-take-in-ukrainian-refugees-it-could-transform-their-economies/

Benezer, G., & Zetter, R. (2015). Searching for directions: Conceptual and methodological challenges in researching refugee journeys. Journal of Refugee Studies, 28(3), 297-318. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feu022

Beresford, A., & Pettit, S. (2021). Humanitarian aid logistics: A Cardiff University research perspective on cases, structures and prospects. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 11(4), 623-638. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-06-2021-0052

Black, D. R. (2017). The challenges of articulating ‘top down’ and ‘bottom up’ development through sport. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 2(1), 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2017.1314771

Block, K., & Gibbs, L. (2017). Promoting social inclusion through sport for refugee-background youth in Australia: Analysing different participation models. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 91-100. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.903

Burnett, C. (2015). The “uptake” of a sport-for-development programme in South Africa. Sport, Education and Society, 20(7), 819-837. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2013.833505

Cain, F. T., & Trussell, D. E. (2019). Methodological challenges in sport and leisure research with youth from refugee backgrounds. World Leisure Journal: Leisure for Children and Youth, 61(4), 303-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2019.1661106

Capalbo, L. S., & Carlman, P. (2022). Understanding participation experiences in sport programs for the acculturation of refugee youth: A comparative study of two different programs in the US and Sweden. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2022.2044101

Cárdenas, A. (2013). Peace building through sport? An introduction to sport for development and peace. Journal of Conflictology, 4(1), 24-33.

Cheung-Gaffney, E. (2018). Sports and humanitarian development: A look at sports programming in the refugee crisis through a case study of KickStart joy soccer project at the Zaatari refugee camp. Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, 28(2). https://doi.org/10.18060/22571

Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as “positive development?”. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 306-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723511417311

Collison, H., Darnell, S., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (2017). The inclusion conundrum: A critical account of youth and gender issues within and beyond sport for development and peace interventions. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.888

Collison, H., & Marchesseault, D. (2018). Finding the missing voices of sport for development and peace (SDP): Using a ‘participatory social interaction research’ methodology and anthropological perspectives within African developing countries. Sport in Society, 21(2), 226-242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1179732

Dagkas, S., Benn, T., & Jawad, H. (2011). Multiple voices: Improving participation of Muslim girls in physical education and school sport. Sport, Education and Society, 16(2), 223-239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2011.540427

Darnell, S. (2014). Critical considerations for sport for development and peace policy development. In O. Dudfield (Ed.) Strengthening Sport for Development and Peace: National Policies and Strategies (pp. 25-29). Commonwealth Secretariat.

Darnell, S. C., & Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2011). Sport for decolonization: Exploring a new praxis of sport for development. Progress in Development Studies, 11(3), 183-196. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100301

Doidge, M., Keech, M., & Sandri, E. (2020). ‘Active integration’: Sport clubs taking an active role in the integration of refugees. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1717580

Dukic, D. MacDonald, B., & Spaaij, R. (2017). Being able to play: Experiences of social inclusion and exclusion within a football team of people seeking asylum. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 101-110. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.892

Dumont, J. C., & Lauren, A. (2022, July 27). The potential contribution of Ukrainian refugees to the labour force in European host countries. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/the-potential-contribution-of-ukrainian-refugees-to-the-labour-force-in-european-host-countries_e88a6a55-en;jsessionid=t-64P-lMms-PPnIUwrwADZQRyqDENrvnVbYN6qlg.ip-10-240-5-84

Edge, S., Newbold, K., & McKeary, M. (2014). Exploring socio-cultural factors that mediate, facilitate, & constrain the health and empowerment of refugee youth. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 34-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.025

Elden, S. (2007). There is a politics of space because space is political: Henri Lefebvre and the production of space. Radical Philosophy Review: RPR, 10(2), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.5840/radphilrev20071022

Fuchs, C. (2019). Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space and the critical theory of communication. Communication Theory, 29(2), 129-150. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qty025

Garamvölgyi, B., Bardocz-Bencsik, M., & Dóczi, T. (2022). Mapping the role of grassroots sport in public diplomacy. Sport in Society, 25(5), 889-907. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1807955

Giulianotti, R., Coalter, F., Collison, H., & Darnell, S. C. (2019). Rethinking sportland: A new research agenda for the sport for development and peace sector. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 43(6), 411-437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519867590

Giulianotti, R., Hognestad, H., & Spaaij, R. (2016). Sport for development and peace: Power, politics, and patronage. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1(3-4), 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2016.1231926

Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (2004). The globalization of football: A study in the glocalization of the ‘serious life’. The British Journal of Sociology, 55(4), 545-568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00037.x

Gottdiener, M. (1993). A Marx for our time: Henri Lefebvre and the production of space. Sociological Theory, 11(1), 129-134. https://doi.org/10.2307/201984

Hadfield, K., Ostrowski, A., & Ungar, M. (2017). What can we expect of the mental health and well-being of Syrian refugee children and adolescents in Canada? Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 58(2), 194-201. 0 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cap0000102

Hartmann, D., & Kwauk, C. (2011). Sport and development: An overview, critique, and reconstruction. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 284-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723511416986

Hartonen, V. R., Väisänen, P., Karlsson, L., & Pöllänen, S. (2022). A stage of limbo: A meta‐synthesis of refugees’ liminality. Applied Psychology, 71(3), 1132-1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12349

Haudenhuyse, R., Hayton, J., Parnell, D., Verkooijen, K., & Delheye, P. (2020). Boundary spanning in sport for development: Opening transdisciplinary and intersectoral perspectives. Social Inclusion, 8(3), 123-128. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v8i3.3531

Hayday, E. J., Collison, H., & Kohe, G. Z. (2020). Landscapes of tension, tribalism and toxicity: Configuring a spatial politics of e-sport communities. Leisure Studies, 40(2), 139-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1808049

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-task-force-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/iasc-guidelines-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings-2007

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review, 10(1-2), 18-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

Kang, S., & Svensson, P. G. (2019). Shared leadership in sport for development and peace: A conceptual framework of antecedents and outcomes. Sport Management Review, 22(4), 464-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.010

Karplus, Y., & Meir, A. (2013). The production of space: A neglected perspective in pastoral research. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 31(1), 23-42. https://doi.org/10.1068/d13111

Keles, S., Friborg, O., Idsøe, T., Sirin, S., & Oppedal, B. (2018). Resilience and acculturation among unaccompanied refugee minors. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(1), 52-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416658136

Kohe, G. Z., & Collison, H. (2020). Playing on common ground: Spaces of sport, education and corporate connectivity, contestation and creativity. Sport in Society, 23(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1555219

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.) Oxford: Blackwell.

Ley, C., & Barrio, M. R. (2019). Promoting health of refugees in and through sport and physical activity: A psychosocial, trauma-sensitive approach. In T. Wezdel and B. Droždek (Eds.) An uncertain safety: Integrative health care for the 21st century refugees (pp. 301-343). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72914-5_13

Lindsey, I., & Darby, P.. (2019). Sport and the sustainable development goals: Where is the policy coherence? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(7), 793-812. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217752651

Luguetti, C., Singehebhuye, L., & Spaaij, R. (2021): ‘Stop mocking, start respecting’: an activist approach meets African Australian refugee-background young women in grassroots football. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(1), 119-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1879920

Luguetti, C., Singehebhuye, L., & Spaaij, R. (2022). Towards a culturally relevant sport pedagogy: Lessons learned from African Australian refugee-background coaches in grassroots football. Sport, Education and Society, 27(4), 449-461. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1865905

Lyras, A., & Welty Peachey, J. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14, 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

Makhoul, J., Nakkash, R., Harpham, T., & Qutteina, Y. (2013). Community-based participatory research in complex settings: Clean mind-dirty hands. Health Promotion International, 29(3), 510. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat049

Marchesseault, D. J. (2016). The Everyday Breakaway: Participant Perspectives of Everyday Life Within a Sport for Development and Peace Program. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Marfell, A. (2019). ‘We wear dresses, we look pretty’: The feminization and heterosexualization of netball spaces and bodies. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(5), 577-602. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217726539

Marshall, E., Butler, K., Roche, T., Cumming, J., & Taknint, J. (2016). Refugee youth: A review of mental health counselling issues and practices. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000068

Mohammadi, S. (2019). Social inclusion of newly arrived female asylum seekers and refugees through a community sport initiative: The case of Bike Bridge. Sport in Society, 22(6), 1082-1099. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1565391

Nicholson, P. (2010). Evaluating evidence: Dirty hands and clean minds. Occupational Health, 62(12), 19.

Nilsson, H., Saboonchi, F., Gustavsson, C., Malm, A., & Gottvall, M. (2019). Trauma-afflicted refugees’ experiences of participating in physical activity and exercise treatment: A qualitative study based on focus group discussions. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1699327

O’Donnell, A. W., Stuart, J., Barber, B. L., & Abkhezr, P. (2020). Sport participation may protect socioeconomically disadvantaged youths with refugee backgrounds from experiencing behavioral and emotional difficulties. Journal of Adolescence (London, England.), 85, 148-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.11.003

Parrott, S., Hoewe, J., Fan, M., & Huffman, K. (2019). Portrayals of immigrants and refugees in U.S. news media: Visual framing and its effect on emotions and attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 63(4), 677-697. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1681860

Philo, G., Briant, E., & Donald, P. (2013). Bad News for Refugees. London: Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183p4bm

Pieloch, K., McCullough, M., & Marks, A. (2016). Resilience of children with refugee statuses: A research review. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 330-339. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000073

Pink, M. A., Mahoney, J. W., & Saunders, J. E. (2020). Promoting positive development among youth from refugee and migrant backgrounds: The case of Kicking Goals Together. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, 101790, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101790

Rivera, H., Lynch, J., Li, J., & Obamehinti, F. (2016). Infusing sociocultural perspectives into capacity building activities to meet the needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 57(2A), 320-329. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000076

Robinson, D. B., Robinson, I. M., Currie, V., & Hall, N. (2019). The Syrian Canadian sports club: A community-based participatory action research project with/for Syrian youth refugees. Social Sciences, 8(6), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060163

Rosso, E., & McGrath, R. (2016). Promoting physical activity among children and youth in disadvantaged south Australian CALD communities through alternative community sport opportunities. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 27(2), 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE15092

Ryu, M., & Tuvilla, M. R. S. (2018). Resettled refugee youths’ stories of migration, schooling, and future: Challenging dominant narratives about refugees. The Urban Review, 50(4), 539-558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0455-z

Serafis, D., Greco, S., Pollaroli, C., & Jermini-Martinez Soria, C. (2019). Towards an integrated argumentative approach to multimodal critical discourse analysis: Evidence from the portrayal of refugees and immigrants in Greek newspapers. Critical Discourse Studies, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1701509

Simonsen, C. B., & Ryom, K. (2021). Building bridges: A co-creation intervention preparatory project based on female Syrian refugees’ experiences with physical activity. Action Research (London, England), 1-0. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503211009571

Sleijpen, M., Boeije, H. R., Kleber, R. J., & Mooren, T. (2016). Between power and powerlessness: A meta-ethnography of sources of resilience in young refugees. Ethnicity & Health, 21(2), 158-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2015.1044946

Spaaij, R., Broerse, J., Oxford, S., Luguetti, C., McLachlan, F., McDonald, B., Klepac, B., Lymbery, L. Bishara, J., & Pankowiak, A. (2019). Sport, refugees, and forced migration: A critical review of the literature. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 1 https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2019.00047

Spaaij, R., & Schaillée, H. (2020). Community-driven sports events as a vehicle for cultural sustainability within the context of forced migration: Lessons from the Amsterdam futsal tournament. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 12(3), 1020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031020

Stanek, Ł. (2007). Space as concrete abstraction: Hegel, Marx, and modern urbanism in Henri Lefebvre. In K. Goonewardena, S. Kipfer, R. Milgrom & C. Schmid (Eds.), Space, difference, everyday life (pp. 76-93). Routledge.

Stewart, L. (1995). Bodies, visions, and spatial politics: A review essay on Henri Lefebvre’s the production of space. Environment and Planning. D: Society & Space, 13(5), 609-618. https://doi.org/10.1068/d130609

The International Platform on Sport and Development. (n.d.) Elite sports and refugees. https://www.sportanddev.org/en/toolkit/sport-and-refugees/elite-sports-and-refugees

Thorpe, H. (2016). Action sports for youth development: Critical insights for the SDP community. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(1), 91-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2014.925952

Thorpe, H., & Ahmad, N. (2015). Youth, action sports and political agency in the middle east: Lessons from a grassroots parkour group in Gaza. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(6), 678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690213490521

UN News. (2022, September 23). Ukraine refugees: Eager to work but need greater support. United Nations. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/09/1127661

UNESCO. (2017). MINEPS VI – Final Report. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259362

UNHCR. (2021a). Refugee Data Finder. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee statistics/download/?url=qZJQ08

UNHCR. (2021b). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf

UNHCR. (2021c). What is a refugee? https://www.unhcr.org/uk/what-is-a-refugee.html

United Nations (2015). “Do you know all 17 SDGs?” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals

van Gennep, A. (1960). The Rites of passage (M. B. Vizedome & G. L. Caffee, Trans.) Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

van Ingen, C. (2003). Geographies of gender, sexuality and race: Reframing the focus on space in sport sociology. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 38(2), 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690203038002004

Weng, S. S., & Lee, J. S. (2015). Why do immigrants and refugees give back to their communities and what can we learn from their civic engagement? Voluntas, 27, 509-524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9636-5

Welty Peachey, J., Musser, A., Shin, N. R., & Cohen, A. (2018). Interrogating the motivations of sport for development and peace practitioners. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(7), 767-787. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216686856

Whitley, M., Collison, H., Darnell, S., Schulenkorf, N., Knee, E., Richards, J., Wright, P., & Holt, N. (2022). Moving beyond disciplinary silos: The potential for transdisciplinary research in sport for development. Journal of Sport for Development, 10(1), 73-94.

Whitley, M. A., & Johnson, A. J. (2015). Using a community-based participatory approach to research and programming in northern Uganda: Two researchers’ confessional tales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 7(5), 620-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2015.1008027

Whitley, M. A., Smith, A. L., Dorsch, T. E., Bowers, M. T., & Centeio, E. E. (2021). Reimagining the Youth Sport System Across the United States: A Commentary From the 2020-2021 President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Science Board. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 92(8), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2021.1963181

Whitley, M. A., & Welty Peachey, J. (2020). Place-based sport for development accelerators: A viable route to sustainable programming? Managing Sport and Leisure, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1825989