Stephen Ojwang1, Rebecca Foster2 and Roselyne A. Odiango3

1 Kenya Academy of Sports, Department of Sports Talent Development

2 University of Worcester, School of Sport and Exercise Science

3 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Department of Health Promotion and Sports Science

Citation:

Ojwang, S., Foster, R. & Odiango, R.A. (2025). Exploring Lived Experiences of Kenyan Para-Athletes: Turning Barriers into Possibilities. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Background: In developing countries, participation and success in elite para-sports are relatively low primarily because of the numerous barriers para-athletes face. The objective of this study, which focused on elite para-athletes from Kenya, was to investigate their lived experiences and how they overcome these barriers to participate and excel at the international level.

Methodology: A qualitative research approach was employed to collect data from the participants through virtual interviews. Five participants (three females and two males) were selected using a purposive sampling strategy and interviewed using semi-structured questions. The data obtained were analyzed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).

Findings: Based on the gathered data, four primary themes emerged: local para-sports events, a supportive environment, media, and international aid. These factors play a crucial role in enabling para-athletes to excel in their respective sports and achieve international recognition.

Conclusion: The lived experiences of para-athletes shed light on strategies for approaching and overcoming barriers to para-sports participation, ultimately leading them to compete at the highest levels of para-sport events. This study provides valuable insights for para-sport practice, policy, and research and can guide the development of intervention programs for para-athletes in developing countries.

INTRODUCTION

The origins of the Modern Paralympic Games can be traced back to the rehabilitation efforts for spinal cord injuries of service members during World War II in the mid-1940s (Brittain, 2019; Patatas et al., 2018). Over the past six decades, the Paralympic Games have evolved to encompass 22 para-sports in summer and six in winter editions (International Paralympic Committee (IPC), n.d.). Participation in these games has experienced steady global growth. Today, the Paralympic Games are widely regarded as the most significant global multi-sport event for athletes with disabilities and are governed by the International Paralympic Committee (Purdue and Howe, 2015; Hums et al., 2023; Legg et al., 2015). The increasing number of countries and athletes participating in the Paralympic Games is evidence of growing interest in and engagement in Paralympic sports worldwide (Brittain, 2019; Legg and Dottori, 2017).

Previous research suggests, however, that disparities in participation and achievement persist in the Paralympic Games. Oggero et al. (2021), in their comparison of trends in Paralympians’ participation and achievements in the Summer Paralympic Games by income level and gender, affirm that over the last 15 Summer Paralympic Games (from 1960 to 2016), high-income and upper middle-income countries have significantly higher rates of achievement than low-income countries. Furthermore, the all-time Paralympic Summer Games medal standings are dominated by high-income countries such as the United States of America, Great Britain, China, and Canada (IPC, n.d.). Studies focusing on similar international competitions suggest that developing countries often send smaller teams compared to developed countries and are less represented in global medal tables (Swartz et al., 2016; Forber-Pratt et al., 2013). In low-income countries, medal achievements are primarily dominated by just four countries: Nigeria, Kenya, Mozambique, and Myanmar (Oggero et al., 2021).

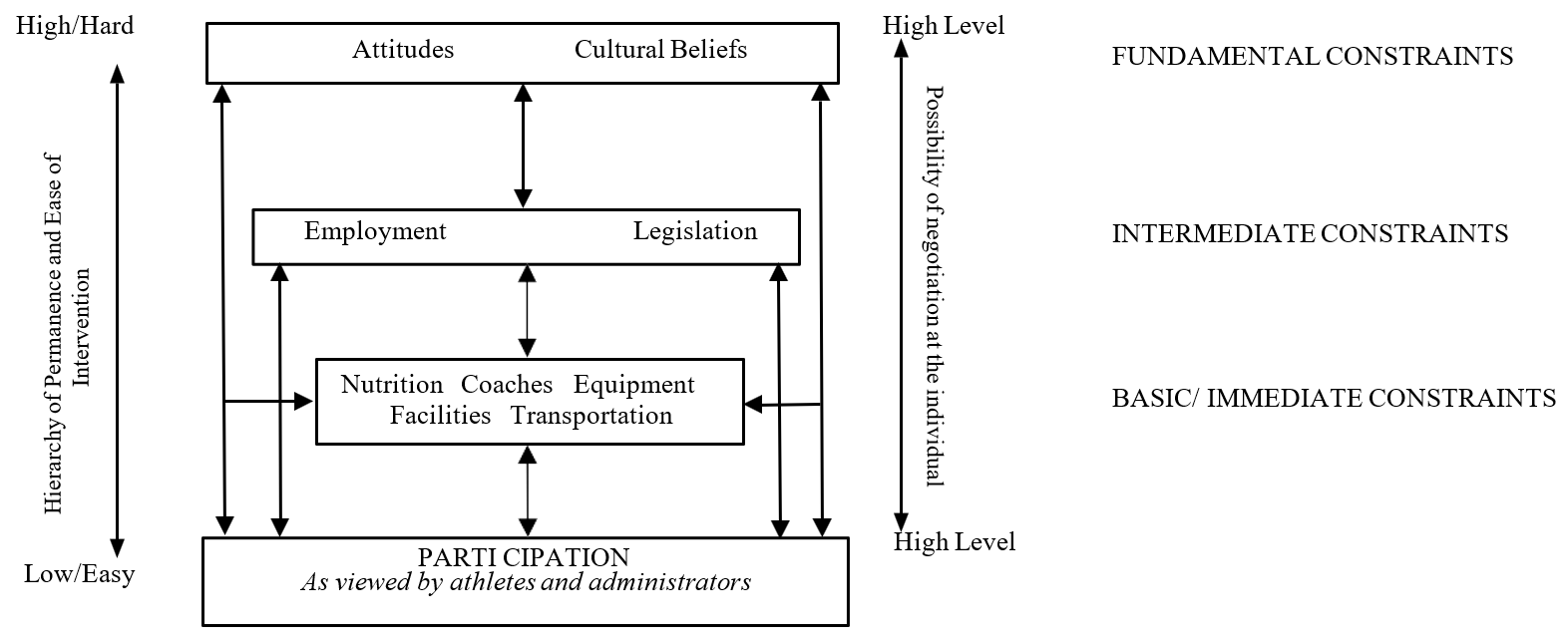

Several studies attribute the low participation and performance of developing countries in the Paralympic Games to various factors. According to Brittain (2019), Buts et al. (2013), and Crawford & Stodolska (2008), athletes from developing countries face numerous challenges in terms of participation and achieving success in para-games. Crawford and Stodolska (2008), while exploring the constraints experienced by elite Kenyan para-athletes, classified these constraints into three categories: basic, intermediate, and fundamental, as shown in Figure 1. This classification is based on the extent to which constraints are deeply ingrained in societal structures and athletes’ ability to navigate them at an individual level.

Figure 1 – Classification of constraints to Para sports participation and performance (Crawford & Stodolska, 2008)

Crawford and Stodolska (2008) state that the basic constraints are immediate barriers that affect individuals at a personal level and can be negotiated individually by athletes. The intermediate constraints are impediments ingrained in the societal structure but may be more manageable to address at a collective level. On the other hand, fundamental constraints refer to barriers deeply embedded within the societal structure, making it challenging for individuals to overcome them at a personal or collective level.

Other studies on para-sports barriers to participation in developing countries have highlighted issues related to resources, technical personnel, and transportation. Legg et al. (2022) and Wickenden et al. (2020) identified coaching as a major challenge faced by para-athletes in the global south. These include inconsistent coaching and inadequately qualified coaches, both of which significantly affect the involvement and success of para-athletes. Townsend et al. (2021) asserted that proper coaching is a crucial factor in enhancing the skills of para-athletes, enabling them to compete more efficiently at both the national and international levels.

Novak (2017) and Thangu (2015) acknowledge that sub-Saharan African countries face challenges related to limited resources in para-sports, significantly affecting para-athlete participation and performance. One of the main issues is the scarcity of specialized equipment for para-sports, making it difficult for athletes to access appropriate and efficient equipment . McNamee et al. (2021) argue that even when such equipment is available, it often comes with exorbitant costs for para-athletes.

For instance, a high-quality basketball wheelchair can cost up to $5,000, and a racing wheelchair designed for speed and agility costs just over $6,000 (RGK, n.d.). The chairs are manufactured abroad and incur additional import charges. These high costs make it nearly impossible for many para-athletes in developing countries who already grapple with socioeconomic hardships. In most cases, some athletes resort to using non-standard equipment, which not only poses injury risks but also hampers their performance at international levels where state-of-the-art equipment is common.

According to Patatas et al. (2018), para-sports in developing economies receive less attention and support from their governments compared to able-bodied sports. Consequently, there is lack of sufficient investment in para-sports facilities and coach development programs. Khumalo et al. (2013), in their investigation of participants trends in wheelchair sports in Zimbabwe, assert that existing sports facilities are often of substandard quality, overcrowded, and built without considering the needs of individuals with disabilities, making them less accessible. The lack of investment in coach development programs hinders the growth and expertise of coaches who play a pivotal role in training and nurturing para-athletes (Hogg, 2018; Taylor, 2015). As a result, the quality of coaching in para-sports remains compromised, affecting the overall performance and potential of para-athletes.

Legg et al. (2022) also note instances of hurtful discrimination and mistreatment among para-athletes by non-disabled players and coaches. This discrimination extends to denying para-athletes access to limited facilities when there is a scheduling conflict. Brittain (2006) also highlights corruption within disability sports federations and organizations in Africa as having a detrimental impact on para-athlete performance. Limited resources allocated to the development of para-sports in most African countries are siphoned off by the federation leaders, leaving little support for athletes (Novak, 2017). These various barriers and constraints pose significant hurdles to para-sports participation in developing countries and consequently have a negative effect on the participation and performance of para-athletes at both national and international levels.

While these challenges are prevalent across many developing countries, this study specifically focused on Kenya. Kenya was chosen as the site for this study for two main reasons: First, Kenya provides a good representation of several developing countries, with its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita ($2,099) placing it roughly in the bottom third of all developing countries (The World Factbook, 2022). Second, Kenya is among the dominant countries in terms of medal success in the Paralympic Games among low – and middle- income countries (Oggero et al., 2021; Brittain, 2019).

Since its establishment in 1989, the Kenya National Paralympic Committee (KNPC) has been a member of the International Paralympic Committee. Kenya’s initial participation in the Paralympic Games dates back to the 1972 Summer Paralympic Games. However, the country did not compete in the subsequent Games held in 1976 but made a comeback in the 1980 Summer Games. Since then, Kenya has consistently participated in all subsequent editions of the Summer Paralympic Games (Buts et al., 2013).

Throughout the records of the Paralympic Summer Games, Kenya has achieved a total of 48 medals, consisting of 18 gold, 16 silver, and 14 bronze medals. This positions Kenya at the 54th spot on the all-time Paralympic Games medal table and fourth among African nations (IPC, n.d.). Kenyan Paralympic athletes have excelled in various sports disciplines, including swimming, powerlifting, and athletics. Notably, most of these medals have been earned by visually impaired athletes, particularly in long- and middle-distance races (Kipkemboi et al., 2019).

Previous studies have highlighted the challenges that para-athletes in developing countries face in sports participation and achievement (Brittain, 2019; Patatas et al., 2018; Novak, 2017; Crawford & Stodolska, 2008; Legg et al., 2022). However, there is a gap in research exploring the narratives of athletes from these countries who have defied the odds to qualify for the Paralympic Games. Additionally, little is known about the factors that enable these para-athletes from developing nations to overcome numerous barriers and qualify for the Games. Therefore, this study aims to explore the experiences of elite Kenyan para-athletes in overcoming barriers and constraints related to their participation and performance in para-sports, and to examine the factors that allowed them to transform these barriers into opportunities.

METHODS

Philosophical Underpinnings

Existing empirical research acknowledges that elite para-sports participation and performance are influenced by individual experiences and lived realities (Allan et al., 2018; Conchar et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2018). This study aimed to gain insights from such experiences by interviewing participants within a specific social and cultural context, particularly in a low-middle income country. To achieve this, a qualitative phenomenological design approach was employed to explore and interpret participants’ responses, guided by the interpretivism paradigm, which encompasses ontological and epistemological constructionism.

According to the interpretivism paradigm, reality is multifaceted, socially constructed, and subjective, with knowledge constructed through interactions with others in social and cultural contexts (Davies & Fisher, 2018; Smith et al., 2016). These principles align with the phenomenological approach, which seeks to explore and understand the essence of human experiences as they are lived and perceived by individuals (Frechette et al., 2020). In this study, the term ‘elite athlete’ refers to para-athletes who have gained international recognition through their participation in events such as regional games, World Championships, Commonwealth Games, and Paralympic Games.

The design also enabled understanding of the para-athletes not as isolated individuals but as relational beings whose experiences are shaped by their interactions with others, including coaches, fellow athletes, family members, and broader societal influences (Patatas et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2016). This relational aspect is crucial for understanding how para-athletes navigate their sporting environments and negotiate their identities within these contexts. Furthermore, the phenomenological approach serves as an empowering data collection method within marginalized communities, such as para-athletes (Niesz et al., 2008). By giving voice to their experiences and validating their perspectives, the study not only contributes to the academic understanding of para-sport but also provides a platform for para-athletes to share their stories and advocate for change within the sports community.

Sampling and Procedures

Prior to participant recruitment, ethical approval was obtained from the University of Worcester Ethics Committee. Participants were provided with an information sheet and given the opportunity to ask questions or raise concerns before providing informed consent through a signed form. Throughout the study, participants were reminded of their right to withdraw without providing reasons.

Participant recruitment followed a criterion-based purposive sampling strategy (Smith et al., 2016). Elite para-athletes from various sports disciplines were sought to ensure the representation of both female and male athletes to capture diverse experiences. Recruitment was conducted through the researcher’s existing network as a technical volunteer for the Kenya National Paralympic Committee. Initially, the researcher aimed to recruit a larger number of participants, ideally up to 15 individuals. However, reaching participants presented challenges due to the dispersed nature of the para-athlete community in Kenya. Some potential participants were difficult to reach because they lacked smartphones and reliable internet access. Additionally, some may have been hesitant to participate due to unfamiliarity with research processes.

Possible participants were initially contacted through WhatsApp messaging to explain the research purpose and gauge their interest in participating. The researcher also disclosed his dual relationship (positionality) to participants, both as a researcher conducting the study and his affiliation with the Kenya Paralympic Committee. Subsequently, parties received a participant information sheet, consent forms, and an interview guide via email. Five participants (three females and two males) were recruited, all of whom wanted their actual names to be used in the report as a platform for their voices to be heard. Each participant had a physical disability, was aged between 20 and 40, and had represented Kenya at international para-games in sports disciplines such as para-powerlifting, para-rowing, wheelchair racing, wheelchair basketball, and wheelchair tennis. Their involvement in sports ranged from 5 to 20 years, and all had classifications according to their respective international sports federations. Table 1 provides detailed demographic information on the participants.

Table 1 – Participants details

| Name | Age category | Sports | Years involved | Classification |

| Stella | 20-30 | Wheelchair basketball | 4 | 2.5 |

| Asiya | 20-30 | Para-rowing Wheelchair tennis |

6 8 |

PR1 ‘Open’ |

| Robert | 20-30 | Wheelchair racing Wheelchair basketball |

7 6 |

T54 1.5 |

| Shaban | 30-40 | Wheelchair tennis | 10 | ‘open’ |

| Hellen | 20-30 | Para powerlifting | 7 | 41kg |

Data Collection

Data were gathered virtually through individual semi-structured interviews conducted over Zoom conference software by the researcher, who was situated in the United Kingdom (UK), while the participants were in Kenya. The decision to employ online interviews was necessitated by the impracticality of conducting face-to-face interviews (Salmons, 2014), which provided a suitable platform for capturing detailed accounts of participants’ lived experiences. The semi-structured interview guide was developed in consultation with the project supervisor, who refined and validated the interview topics. These topics were informed by relevant literature and the research objectives. Once the initial topics were identified, the researcher drafted open-ended questions to explore each topic further during the interviews.

During the interviews, the semi-structured format provided a balance between guidance by the interviewer and freedom for the participants to express themselves (Brown and Danaher, 2019). The interviewer began with broad, open-ended questions related to the predetermined topics but allowed the participants to guide the conversation and delve deeper into areas they considered important. Some of the questions posed were: ‘What are the challenges and rewards of being a para-athlete in Kenya?’ and “Despite the obstacles you encounter, what factors have facilitated your success in Para-sport competitions?” Additionally, the interviewer employed prompts such as “Tell me more…” or “Carry on, please…” to encourage a more comprehensive discussion and to obtain in-depth information. The interviews were recorded on video and had an average duration of 30 minutes. Subsequently, verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were generated to facilitate ease of analysis (Halcomb & Davidson, 2006).

Data Analysis

The video-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim using Microsoft Word transcription software. Some responses were given in Swahili and were initially translated into English before transcription. To ensure the accuracy of these translations, a back-translation method was employed (Colina et al., 2017). This involved translating the Swahili responses into English initially and then translating the English version back into Swahili. The back-translation process aimed to validate the accuracy and consistency of the initial translation while maintaining the meaning of the original content.

The back-translated Swahili responses were compared with the original Swahili responses to identify any discrepancies or changes in meaning. Any discrepancies found between the original and back-translated versions were reviewed, and adjustments were made to the initial translation as needed to ensure accuracy. Behr (2017), in assessing the use of back translation, affirms that this rigorous process helps maintain the integrity of the translations and ensures that the participants’ responses are accurately represented.

The data obtained from the transcriptions were analyzed using the principles of Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith and Fieldsend, 2021). This analytical approach explores how individuals make sense of their own experiences. The primary focus of this study was to conduct a phenomenological investigation to gain deeper insights into the lived experiences of Kenyan para-athletes. The aim was to understand the strategies they employed to overcome barriers that hinder their participation in para-sports and their ability to compete at the international level. The following four steps were used in IPA: a) data familiarization, b) initial code generation and searching for relevant themes, c) review of various themes, and d) naming and defining various themes.

The initial step involved reading and re-reading each transcript to become familiar with its content, which was essential for identifying significant phrases and quotes. Similar phrases and quotes were documented along with notes describing the experiences of the participants and data interpretation. Next, the transcripts were analyzed to identify common themes in the athletes’ narratives, leading to the creation of codes and themes. These themes were then reviewed by comparing the different transcripts of the respondents, establishing connections between the preliminary themes, and refining them. In the final analysis phase, the themes and subthemes were named and organized into a thematic network encompassing all relevant aspects.

To ensure credibility, a peer briefing approach was adopted, engaging one experienced peer in qualitative analysis to discuss emerging themes. As suggested by Devotta et al. (2016), involving multiple reviewers is crucial to minimize bias and improve data reliability. Moreover, member checking was conducted by contacting the participants after the analysis to verify the accuracy and relevance of the identified themes. Participants were reached via email, where they were provided with a summary of the emergent themes and asked to confirm whether they resonated with their experiences. The responses from participants confirmed and agreed with the themes as a true reflection of their lived experiences, thus providing further validation of the analysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results and discussion were combined to enable a comprehensive understanding and analysis of the data (Fetters et al., 2013). From the analysis of the interview transcripts, four main themes emerged, effectively capturing the real-life experiences of elite Kenyan para-athletes and the strategies they utilized to overcome barriers impeding their participation in para-sports and their ability to compete at the international level. These themes were further divided into major themes and sub-themes. Each significant subtheme was substantiated by direct quotes from interviews. The four major themes identified were (a) local para-sports events, (b) supportive environment, (c) media, and (d) international aid. The major themes and sub-themes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 – Major themes and subthemes

| Major Themes | Sub-themes |

| Local Para sport events |

|

| Supportive environment |

|

| Media and broadcasting |

|

| International aids |

|

Local Para-Sport Events

Four out of the five interviewed para-athletes recounted local para-sports events as significant factors in their development and success, with the majority having participated in special school games and community local tournaments.

Special School Games

School games are instrumental in identifying and nurturing talent among Kenyan athletes (Mwangi et al., 2022). Majority of the Kenyan elite para-athletes started competing in special school games, where they developed their skills and gained exposure to competitive sports. Asiya recounted that special school games were a crucial stepping stone to her success:

I was first introduced to wheelchair sports in primary special school, where we used to have special school games every term one and two. I used to compete in wheelchair racing and sometimes wheelchair tennis…this was my very first-time playing sports, it’s when I learned how to push my wheelchair back and forward in the court, and how to play with an opponent

Stella, a young Kenyan wheelchair basketball player, credits her success to the opportunities provided by school games, noting that these games provided her with the platform to develop her love for wheelchair basketball and her determination to succeed:

in secondary school, we participated in inter-house competitions, we played various sports such as sitting volleyball, wheelchair table tennis and basketball…personally I played wheelchair basketball, our games teacher could instruct all the students using wheelchairs to go and play basketball…I played the game since form one to form four and developed my love for the game.

Mwangi (2013) asserted that young special school students in Kenya face several challenges, including limited resources and the need for recognition. However, special school games have emerged as a key stepping stone to the success of many elite para-athletes. Houlihan and Chapman (2017) suggested that one key benefit of school games is the opportunity for young athletes to be exposed to various sports activities. This exposure is often critical in helping athletes identify their strengths and weaknesses and focus their training efforts accordingly. Through the guidance and support of coaches, the young athletes can then identify the most suitable sport discipline in which to specialize.

Grassroots and Local Tournaments

Upon finishing secondary school, the majority of Kenyan para-athletes were not involved in any form of sporting activities due to the lack of a proper channel that could ensure their transition and incorporation into community clubs. It was not until they participated in local events, such as the annual Standard Chartered inclusive marathon, that they were spotted and scouted by national coaches. Robert said:

I stayed home for one year after finishing high school, and then I saw on Facebook that Standard Chartered Bank was looking for people with disability to register for a wheelchair marathon…., that is when I registered and won a gold medal and was scouted by my coach to join the national team.

The Standard Chartered marathon, which integrates the wheelchair category, is Kenya’s locally sponsored inclusive sport event. Purdue and Howe (2015) posit that tournaments are essential for the development of elite para-athletes. They outline the critical roles through which adequate and consistent local tournaments are helpful in para-sport development, including providing a platform for athletes to showcase their talents and network with potential coaches for scouting to join national teams.

Similarly, Shaban, a wheelchair tennis seed 1 for team Kenya, and Hellen, a Commonwealth bronze medalist, emphasized the significance of grassroots and national tournaments in their success. Shaban stated:

Our Federation frequently organizes tournaments and friendly matches at Nairobi Sports Club. Most of the time, we compete against each other for small prize awards, and sometimes we play against players from other counties, such as Mombasa. These local tournaments helped me to play against experienced and talented players from across the country.

Hellen stated:

I used to attend weekend matches at Nyayo Stadium, where I could compete and better my skills. Through these weekend matches, I also had the opportunity to meet Paralympic officials…… they selected me to join the national team for the Paralympic qualifiers.

Local para-sports events play a significant role in the development and success of elite Kenyan para-athletes. These events have provided athletes with an opportunity to compete against their peers, gain exposure to different types of competition, and hone their skills. Kipkemboi et al. (2019) stated that one of the primary benefits of local sports tournaments and camps in Kenya is the opportunity they provide for athletes to showcase their talents. Successful performances at these events have enabled athletes to be selected for national and international competitions.

Supportive Environment

This study found that a supportive environment plays a crucial role in the success of elite Kenyan para-athletes. Many of the interviewed athletes expressed a deep sense of determination and desire to prove themselves because of the support received from various people.

Peer Support and Ally-hip

Peer support and ally-ship provided valuable guidance, motivation, and inspiration, helping Kenyan para-athletes overcome challenges and achieve their full potential. Stella, a wheelchair basketball player, reported this:

There is this friend of mine who first invited me to wheelchair basketball…she was playing the regular basketball… and most of the time we could meet and go together for the training… some days when I missed, she could call me on phone and ask why I was not coming and encouraged me to keep going.

Shaban resounded Stella’s experience of supportive teammates and friends:

The tennis court was miles away from my college, so one of my regular tennis players noticed I was skipping so many training sessions because of the transport fare, so he offered to drive me from home to court and back home three days a week. Since then I was able to attend all my training sessions.

Peer support, mentorship, and ally-ship are essential success factors for elite para-athletes (Houlihan and Chapman, 2017). These forms of support provide emotional reinforcement, guidance, and networks for like-minded individuals. Bundon et al. (2018) posit that peer support and mentorship are beneficial for the immediate needs of para-athletes and contribute to their long-term development. The relationships formed through peer support can extend beyond an athlete’s competitive career, providing a support network for personal and professional growth even after retirement.

Training and coaching

Training and coaching programs are essential for the success of elite para-athletes. Some of the interviewed athletes expressed that their coaches are friendly and understand their unique challenges and requirements. This understanding enables the development of effective training strategies and enhances their playing skills. Stella confirmed:

Our coach, who is a former international basketball player, has a good understanding of wheelchair basketball. He conducts good training sessions for us. He is not living with any disability, but he sits on the wheelchair and plays together with us during the training sessions…he is also very friendly and takes care of our concerns off the court… his guidance and support has helped us participate well in commonwealth games.

Shaban added:

My current coach was my very first coach eight years ago when I first joined wheelchair tennis at the college, we met when I was in my first year at the college in Mombasa, he has been my best friend for a long time, this is the guy who taught me all the basics of tennis to top skills…he understands my individual needs in and out the court.

The existing literature suggests that elite para-athletes require specialized coaching and expert guidance tailored to meet their specific needs (Darcy et al., 2017). Itoh et al. (2018) also suggest former female Paralympians face numerous barriers when attempting to transition into coaching roles, these challenges often prevent them from sharing their invaluable understanding and unique perspectives as coaches with disabilities. Para-athletes face unique challenges due to their disabilities; specialized training helps them optimize their physical abilities, develop particular skills, and enhance their overall performance (Dehghansai et al., 2020). Hellen commented:

My coach is more than just a coach. He is like a brother to me because he is always available whenever I am in need…Sometimes he comes home to check on me, he brings me some shopping when I need some items… He has also helped me build mental toughness and believe in myself, which has been helpful to me as a para-powerlifter.

Para-athletes often encounter unique psychological challenges related to their disabilities, such as low self-esteem and mental health vulnerability (Olive et al., 2021). Specialized coaching provides psychological support, including goal setting, cognitive skills training, and strategies to cope with setbacks, enabling athletes to develop a strong mindset and perform under pressure (Powell and Myers,2017). During the athlete interviews, further psychological support was mentioned. Asiya discussed:

Competing in para-rowing has many challenges, but my coach has been supportive… He keeps encouraging and telling me to focus on the major goal of qualifying for the Paralympic games…his encouraging words and support greatly helped me to qualify for the Tokyo Paralympics in 2020.

Family support

Family support plays a significant role as a success factor for elite para-athletes. The interviewed athletes highlighted the importance of family support during their journey toward elite sports. Many athletes faced significant challenges in their personal lives, including stigmatization and discrimination, but found strength from their supporting families. Stella remarked:

When I first joined wheelchair basketball, I was living with my sister in Thika town, some distance away from the training stadium in Nairobi, but because she was very happy with the idea of playing basketball, she used to drive me with her car to the stadium and pick me up in the evenings every Saturday. This enabled me to master the skills quick and join the main team within the first year I joined.

McLoughlin et al. (2017) as well as Peake and Davies (2022) emphasized that pursuing a career in para-sports requires financial resources for training, equipment, travel, and participation in competitions. Elite Kenyan para-athletes often need funding and adequate support from sports organizations (Brittain, 2019) and so family support is crucial under such circumstances. This support system is crucial for para-athletes as they navigate the challenges of training, competition, and personal growth. The support system can alleviate the financial burden on athletes and allow them to focus on their training and performance. One para-athlete, Asiya, acknowledged the financial aid accorded to her by family members and friends:

I was supposed to go for the Tokyo Paralympic qualifiers [sic] in 2019 in Tunis. I was disappointed when the federation told me they would not sponsor any para-rower due to lack of funds…the government also could not provide funding because they were only funding the regular athletes…I was so stranded but then my family and friends came together to raise money for my airfare. I eventually managed to travel for the qualifiers [sic] …I emerged position one in the women’s single category and qualified for the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games.

The disparity in funding between para-athletes and other athletes in Kenya is evident, highlighting a systemic inequality by governmental agencies and sporting federations. While able-bodied athletes receive more financial support than para-athletes, including extensive training facilities and sponsorship deals, para-athletes are often left to navigate a landscape devoid of sufficient resources.

The lack of financial support greatly affects the para-athletes who already face additional challenges and expenses due to their disabilities. While Asiya was fortunate to receive support from her family and friends, not all athletes have access to such resources. Without adequate funding, many talented para-athletes may never get the opportunity to showcase their abilities on the global stage. This inequity not only undermines the potential of para-athletes but also reinforces societal stigmas surrounding disability, further marginalizing this already vulnerable population.

Media

The Kenyan local media is a powerful platform for promoting elite para-athletes’ achievements, raising awareness, and generating support for para-sports. Stella, a young wheelchair basketball player competing in the Commonwealth 2022 Games during the study, reported that:

I was called for a media interview about these ongoing Commonwealth games, and the Kenya Broadcasting channel reported some of our matches during the sports news… Twitter handles for the Kenya Olympics also promoted all Kenyan teams in Birmingham, including the wheelchair basketball team. I believe this has got us being watched back home and worldwide.

Media exposure also provides a platform for Kenyan para-athletes to share their stories, inspire others, raise awareness on disability sports, and promote inclusion and diversity. Asiya recounted her experience with a Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) interview:

during my Tokyo Paralympic preparations, I was invited by the KBC sports for an interview… I talked about my journey from when I was a young kid, the time when I got an accident and got disabled, to the challenges I have overcome in playing sports to now qualifying for Paralympics as the first female Kenyan para-rower… at the end of the interview, I asked them to go show the video of the interview to special school kids, I wanted the kids to get motivated and know that everything is possible… yes I’m told they went to my former school and played the video to the students… and I’m hoping it motivated them to believe in their dreams.

Media coverage provides para-athletes with increased visibility and recognition both nationally and internationally (Burton et al., 2021; McGillivray et al., 2021). Media showcases their accomplishments, personal stories, and the challenges they overcome through news articles, feature stories, interviews, and television events. This promotes the understanding that disability is not a limitation to pursuing athletic excellence.

Howe and Silva (2018) suggest that by challenging misconceptions and educating the public, media can foster an environment in which para-athletes can be seen as athletes first, with their disabilities being just one aspect of their identity. Robert, a wheelchair basketball player who doubles as a disc jockey on a local radio station, acknowledged how he employs his talent to challenge societal stereotypes and misconceptions about disability:

In Kenya, people believe that individuals with disabilities cannot achieve certain goals. We are often seen as beggars, but through my radio shows, I show them that we are also capable, and nothing can hold us back…sometimes we visit special schools in the weekends for entertainment, and during these visits, I also talk to the students about my para-sports achievement and encourage them to participate in sports.

International Aid

Drawing on the work of Maleske and Sant (2022), international aid can catalyze the success of elite para-athletes in less-developed countries by providing financial support, access to resources, and coaching expertise. This aid not only enhances athletes’ performance, but also contributes to the growth and development of para-sports in developing countries.

Donations

International donations help address the financial challenges of acquiring adaptive sports equipment in developing countries (Mojtahedi and Katsui, 2018). Elite para-athletes often require specialized equipment tailored to their specific disabilities. International aid sources have donated or provided funding to purchase some of this equipment, ensuring that Kenyan para-athletes have access to some of the tools they need to train and compete internationally (Legg et al., 2022). The generosity of international donors has played a crucial role in empowering Kenyan elite para-athletes and facilitating their journey toward success, as explained in the following extract from Stella:

In 2012, when we were travelling to Morocco for the Paralympic qualifiers, the British High Commission donated 12 wheelchairs to us. We have used these wheelchairs until recently when we were heading for the Commonwealth 2022 games, then we received another set of donations from six wheelchairs from UK Aid.

International projects /programs

International flagship programs such as ‘Gather Adjust Prepare & Sustain’ (GAPS), designed by the Commonwealth Sports Federation to inspire and enable athletes from less developed countries to reach their sporting potential through global pathways and competitions (Riot et al., 2020), have facilitated training opportunities for some Kenyan para-athletes. In this study, a para-powerlifting athlete, Hellen, stated how the international program contributed to her development and success:

I am a GAPS supported athlete, I have attended two international training camps sponsored by GAPS, one at Glasgow in 2018 and 2022 at Birmingham University… through these camps, I have received training from world-class coaches and access to good facilities…these trainings have helped me win some medals.

Through collaboration with universities, coaches, and experts, commonwealth para-athletes can access specialized training techniques, knowledge, and skills to improve their athletic performance through the GAPS program (Riot et al., 2020). This support has enabled Kenyan para-athletes under the program to compete and secure medals on the international stage.

The IPC has also been actively engaged in developmental initiatives in Africa and maintains a close partnership with the Kenya National Paralympic Committee (The Paralympian, 2003). According to Robert,

in 2016, when we were preparing for the Rio Paralympic Games, we did a 500 kilometer (km) “Road to Rio” wheelchair challenge, that was financially supported by Agitos Foundation…this very long-distance challenge from Nairobi to Mombasa that is 400km, made us to prepare for the Paralympic marathon.

To advance disability sports globally, the IPC has established a preliminary equivalent to the Olympic Solidarity initiative (Misener and Wasser, 2016), the Agitos Foundation. This Foundation, which falls under the purview of the IPC, focuses on education and development within para-sports and administers several programs aimed at enhancing the participation, development, and performance of para-athletes in developing countries.

Proposed Interventions

The results of this study reveal that Kenyan para-athletes heavily rely on assistance from their coaches, family members, private sectors, and international aid to compete at the international level. The responses from the athletes indicate that the government has not offered sufficient support aimed at developing their talents and adequately facilitating their participation in elite competitions. The discussions suggest that government agencies, such as the Ministry of Sports, Kenya Academy of Sports, and Kenya National Paralympic Committee, should institute a committee to further investigate the challenges that affect para-athletes and para-sport development in Kenya. This committee should also aim to tap into the strengths highlighted by elite para-athletes in managing these challenges.

The insufficient funding of Kenyan para-athletes by the government agencies is glaring. Efforts to address this issue should involve collaboration between government agencies, sporting federations, corporate sponsors, and civil society organizations. Creating sustainable funding mechanisms and support structures ensure that para-athletes have the resources they need to thrive and succeed in their athletic pursuits. Additionally, raising awareness about the challenges faced by para-athletes and the importance of inclusive support can mobilize public and private support for their cause.

Media exposure has proven to be a driving force for many successful Kenyan para-athletes. Therefore, Kenyan media should intensify efforts to cover both local and international para-sports activities. This increased coverage will raise awareness and help diminish the social stigma against disability by showcasing the incredible talents and achievements of para-athletes. Additionally, conducting more interviews with para-athletes to share their personal stories and paths to success could attract potential sponsors and donors from the private sector. This, in turn, can lead to increased financial support, enabling athletes to access better training facilities, equipment, and resources to further their sporting careers.

Emphasis should also be put on empowering para-athletes through advocacy and support groups, facilitating networking and collaboration among para-athletes, disability sports organizations, and civil society organizations. These connections create a platform on which knowledge and experiences are shared, best practices are developed, and mentorship opportunities arise. Moreover, collaboration and networking provide para-athletes with access to guidance, resources, and opportunities for personal and professional growth, contributing to their performance in para-sports and life.

Study Limitations

This study had two limitations. First, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to all para-athletes in Kenya. The present study focused only on a few elite para-athletes; it did not reflect the state of sport for people with disabilities at the grassroots level, where a more significant proportion of athletes with disabilities exists. Second, all participants in this study were living with physical disabilities. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to all elite Kenyan para-athletes with other disabilities. Nevertheless, the results of this study provide a suitable guide for future research on the experiences of para-athletes in developing countries and may lead to increased participation and performance in para-sports.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the lived experiences of elite Kenyan para-athletes in overcoming barriers to participation and performance in para-sports. The findings of this study highlight various coping mechanisms and success factors expressed by elite Kenyan para-athletes. Despite facing significant barriers, Kenyan para-athletes have turned these obstacles into possibilities through participation in local para-sports events, supportive environments, media exposure, and international aid. This underscores the importance of special school games and local tournaments, training and coaching, family support, media interviews, and international donations and programs in their achievements. This study also emphasized the need for more resources and support to enable para-athletes to reach their full potential.

Finally, this study enhances our knowledge of elite para-athletes’ experiences, especially in a developing country context. Further research is needed to explore the experiences of para-athletes in other developing countries and to identify strategies for promoting greater inclusion and development of para-sports.

AUTHOR NOTE

Rebecca Foster MBE contributed to the design and implementation of the research and Dr. Roselyne Odiango contributed to the analysis of the research findings. The authors declare no potential conflict of interests with respect to the research and authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors also declare there was no source of funding for this research.

REFERENCES

Allan, V., Smith, B., Côté, J., Ginis, K.A.M., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Narratives of participation among individuals with physical disabilities: A life-course analysis of athletes’ experiences and development in parasport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 170-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.004

Behr, D. (2017). Assessing the use of back translation: The shortcomings of back translation as a quality testing method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 573-584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1252188

Brittain, I. (2019). The impact of resource inequality upon participation and success at the summer and winter Paralympic Games. Journal of Paralympic Research Group, 12, 41-67. https://doi.org/10.32229/parasapo.12.0_41

Brittain, I., 2006. Paralympic success as a measure of national social and economic development. International Journal of Eastern Sport and Physical Education, 4(1), 38-47.

Brown, A. & Danaher, P.A., 2019. CHE principles: Facilitating authentic and dialogical semi-structured interviews in educational research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(1), 76-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2017.1379987

Bundon, A., Ashfield, A., Smith, B., & Goosey-Tolfrey, V. L. (2018). Struggling to stay and struggling to leave: The experiences of elite para-athletes at the end of their sport careers. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 296-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.04.007

Burton, N., Naraine, M. L., & Scott, O. (2021). Exploring Paralympic digital sponsorship

strategy: An analysis of social media activation. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2021.1990789

Buts, C., Bois, C. D., Heyndels, B., & Jegers, M. (2013). Socioeconomic determinants of success at the Summer Paralympics. Journal of Sports Economics, 14(2), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002511416511

Colina, S., Marrone, N., Ingram, M., & Sánchez, D. (2017). Translation quality assessment in health research: A functionalist alternative to back-translation. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 40(3), 267-293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278716648191

Conchar, L., Bantjes, J., Swartz, L., & Derman, W. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity: The experiences of a group of South African adolescents with cerebral palsy. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(2), 152-163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314523305

Crawford, J.L. & Stodolska, M., 2008. Constraints experienced by elite athletes with disabilities in Kenya, with implications for the development of a new hierarchical model of constraints at the societal level. Journal of Leisure Research, 40(1), 128-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2008.11950136

Darcy, S., Lock, D., & Taylor, T. (2017). Enabling inclusive sports participation: Effects of disability and support needs on constraints to sport participation. Leisure Sciences, 39(1), 20-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1151842

Davies, C. & Fisher, M. (2018). Understanding research paradigms. Journal of the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses Association, 21(3), 21-25. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.160174725752074

Dehghansai, N., Lemez, S., Wattie, N., Pinder, R.A. & Baker, J., 2020. Understanding the development of elite parasport athletes using a constraint-led approach: Considerations for coaches and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 502981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.502981

Devotta, K., Woodhall-Melnik, J., Pedersen, C., Wendaferew, A., Dowbor, T. P., Guilcher, S. J., Hamilton-Wright, S., Ferentzy, P., Hwang, S.W., & Matheson, F.I. (2016). Enriching qualitative research by engaging peer interviewers: a case study. Qualitative Research, 16(6), 661-680. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115626244

Evans, M. B., Shirazipour, C. H., Allan, V., Zanhour, M., Sweet, S. N., Ginis, K. A. M., & Latimer-Cheung, A. E. (2018). Integrating insights from the parasport community to understand optimal experiences: The Quality Parasport Participation Framework. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 37, 79-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.04.009

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134-2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Forber-Pratt, A. J., Scott, J. A., & Driscoll, J. (2013). An emerging model for grassroots Paralympic sport development: A comparative case study. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 3(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v03i01/53894

Frechette, J., Bitzas, V., Aubry, M., Kilpatrick, K., & Lavoie-Tremblay, M. (2020). Capturing lived experience: Methodological considerations for interpretive phenomenological inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920907254

Halcomb, E.J. & Davidson, P.M., 2006. Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Applied Nursing Research, 19(1), 38-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2005.06.001

Hogg, L. R. (2018). Pathways to the Paralympic games: Exploring the sporting journeys of high-performance para-athletes with a limb deficiency (Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology). https://hdl.handle.net/10292/11841

Houlihan, B. & Chapman, P. (2017). Talent identification and development in elite youth disability sport. In B. Skirstad, M.M. Parent, & B. Houlihan (Eds.), Young people and sport (1st ed., pp. 107-125. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351271882

Howe, P. D., & Silva, C. F. (2018). The fiddle of using the Paralympic Games as a vehicle for expanding [dis]ability sport participation. Sport in Society, 21(1), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1225885

Hums, M. A., Kluch, Y., Schmidt, S. H., & MacLean, J. C. (2023). Governance and policy in sport organizations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003303183

International Paralympic Committee. (n.d.). Paralympic Games Results. Paralympic games results. https://www.paralympic.org/paralympic-games-results

Itoh, M., Hums, M. A., Arai, A., & Ogasawara, E. (2018). Realizing identity and overcoming barriers: Factors influencing female Japanese Paralympians to become coaches. International Journal of Sport and Health Science, 16, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.5432/ijshs.201630

Khumalo, B., Onyewandume, I., Bae, J., & Dube, S. (2013). An investigation into participation trends by wheelchair sports players at the Zimbabwe Paralympic Games. Sport and Art, 1(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.13189/saj.2013.010101

Kipkemboi, K. J., Ng’ang’a, W., & Otuya, R. (2019). Effects of camps/clubs on performance of Kenya para-athletes. [Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta university]. http://41.89.164.27/handle/123456789/1007

Legg, D., & Dottori, M. (2017). Marketing and sponsorship at the Paralympic Games. Managing the Paralympics, 263-288. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-43522-4_12

Legg, D., Fay, T., Wolff, E., & Hums, M. (2015). The International Olympic Committee–International Paralympic Committee relationship: Past, present, and future. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 39(5), 371-395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514557822

Legg, D., Higgs, C., Douer, O.F., Bukhala, P. and Pankowiak, A., 2022. A framework for understanding barriers to participation in sport for persons with disability. Palaestra, 36(1), 13-21.

Maleske, C., & Sant, S. L. (2022). The role of development programs in enhancing the organizational capacity of National Paralympic Committees: A case study of the road to the games program. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(5), 451-469. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1819862

McGillivray, D., O’Donnell, H., McPherson, G., & Misener, L. (2021). Repurposing the (super) crip: Media representations of disability at the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games. Communication & Sport, 9(1), 3-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479519853496

McLoughlin, G., Fecske, C. W., Castaneda, Y., Gwin, C., & Graber, K. (2017). Sport participation for elite athletes with physical disabilities: Motivations, barriers, and facilitators. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(4), 421-441. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2016-0127

McNamee, M., Parnell, R., & Vanlandewijck, Y. (2021). Fairness, technology and the ethics of Paralympic sport classification. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(11), 1510-1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2021.1961022

Misener, L., & Wasser, K. (2016). International sport development. In E. Sherry, N. Schulenkorf, & P. Phillips (Eds.), Managing sport development: An international approach (1st ed., pp. 31-44). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315754055

Mojtahedi, M. C., & Katsui, H. (2018). Making the right real! A case study on the implementation of the right to sport for persons with disabilities in Ethiopia. In F. Kiuppis (Ed.), Sport and disability: From integration continuum to inclusion spectrum (1st ed., 40-49). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429505317

Mwangi, L. (2013). Special Needs Education (SNE) in Kenyan public primary schools: exploring government policy and teachers’ understandings [Doctoral dissertation, Brunel University]. Brunel University School of Sport and Education PhD Theses. http://bura.brunel.ac.uk/handle/2438/7767

Mwangi, M. T., Kigo, J., & Owiti, B. (2022). The impact of investment in sports teachers training on pupils’participation in sporting activities in public primary schools in Kenya. European Journal of Education Studies, 9(3), 44-61. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v9i3.4198

Niesz, T., Koch, L., & Rumrill, P. D. (2008). The empowerment of people with disabilities through qualitative research. Work, 31(1), 113-125.

Novak, A., 2017. Disability sport in Sub-Saharan Africa: From economic underdevelopment to uneven empowerment. Disability and the Global South, 1(1), 44-63.

Oggero, G., Puli, L., Smith, E.M. and Khasnabis, C., 2021. Participation and achievement in the Summer Paralympic Games: The influence of income, sex, and assistive technology. Sustainability, 13, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111758

Olive, L. S., Rice, S., Butterworth, M., Clements, M., & Purcell, R. (2021). Do rates of mental health symptoms in currently competing elite athletes in paralympic sports differ from non-para-athletes?. Sports Medicine-Open, 7(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00352-4

Patatas, J.M., De Bosscher, V., De Cocq, S., Jacobs, S., & Legg, D. (2021). Towards a system theoretical understanding of the parasport context. Journal of global sport management, 6(1), 87-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2019.1604078

Patatas, J. M., De Bosscher, V., & Legg, D. (2018). Understanding parasport: An analysis of the differences between able-bodied and parasport from a sport policy perspective. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(2), 235-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1359649

Peake, R., & Davies, L. E. (2022). International sporting success factors in GB para-track and field. Managing Sport and Leisure, 29(2), 324-339. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2022.2046487

Powell, A. J., & Myers, T. D. (2017). Developing mental toughness: Lessons from paralympians. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01270

Purdue, D.E. & Howe, P.D., 2015. Plotting a Paralympic field: An elite disability sport competition viewed through Bourdieu’s sociological lens. International Review for the Sociology of Ssport, 50(1), 83-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212470123

RGK Wheelchairs. (n.d). Premium made to measure wheelchairs. https://rgkwheelchairs.com/

Riot, C., O’Brien, W., & Minahan, C. (2020). High performance sport programs and emplaced performance capital in elite athletes from developing nations. Sport Management Review, 23(5), 913-924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.11.001

Salmons, J. (2015). Qualitative online interviews: Strategies, design, and skills. Sage Publications. Routledge.

Santos, F., Camiré, M., & Mac Donald, D. J. (2018). Lived experiences within a longstanding coach-athlete relationship.: The case of one paralympic athlete. Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, 20(2-3), 279-297.

Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2016). Interviews: Qualitative interviewing in the sport and exercise sciences. In Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 125-145). Routledge.

Smith, B., Bundon, A. & Best, M. (2016). Disability sport and activist identities: A qualitative study of narratives of activism among elite athletes with impairment. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 26, 139-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.07.003

Smith, J. A., & Fieldsend, M. (2021). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In P. M. Camic (Ed.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (2nd ed., pp. 147–166). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000252-008

Swartz, L., Bantjes, J., Rall, D., Ferreira, S., Blauwet, C., & Derman, W. (2016). “A more equitable society”: The politics of global fairness in paralympic sport. PloS ONE, 11(12), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167481

Taylor, S. (2015). Case studies in learning to coach athletes with disabilities: Lifelong learning in four Canadian parasport coaches [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa].

Thangu, E.K., 2015. Performance of Kenyan athletes with physical impairments on classification activity limitation tests for running events and related influencing contextual factors [Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University].

The World Factbook. (2022). https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/archives/2022/

Townsend, R. C., Smith, B., & Cushion, C. J. (2015). Disability sports coaching: Towards a critical understanding. Sports Coaching Review, 4(2), 80-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2016.1157324

Townsend, R.C. & Cushion, C.J., 2021. ‘Put that in your… research’: Reflexivity, ethnography and disability sport coaching. Qualitative Research, 21(2), 251-267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120931349

Wickenden, M., Thompson, S., Mader, P., Brown, S. & Rohwerder, B., 2020. Accelerating disability inclusive formal employment in Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda: What are the vital ingredients? The Institute of Development Studies and Partner Organizations. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12413/15198