Katrin Bauer1, Nico Schulenkorf2 and Katja Siefken3

1 Freelance Researcher, Tübingen, Germany

2 Centre for Sport, Business and Society, UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

2 Centre for Sport Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

3 Institute of Interdisciplinary Exercise Science and Sports Medicine (IIES), Medical School Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Citation:

Bauer, K., Schulenkorf, N. & Siefken, K. (2024). From academic silos to interdisciplinary engagement: Understanding and advancing research and evaluation in Sport for Development. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Over the last 20 years, the growing recognition of sport as an enabler of sustainable development has allowed Sport for Development (SFD) to emerge as a dynamic research field featuring contributions from a wide range of scholarly disciplines. Within this research, evaluation has played a prominent role, especially against the background of omnipresent demands to ‘prove impact’ and legitimize the field. Despite the growth of scholarly activity, the field remains largely scattered with limited interdisciplinary engagement. This article presents an overview of the conceptualization and implementation of SFD research and evaluation, encompassing study types and methodological approaches. Findings were generated from a scoping review of publications on research and evaluation activities in the SFD field, guided by the newly proposed Evaluation Research Framework. They highlight that the field is suffering from terminological imprecisions that lead to vague and often undifferentiated debates about methodologies and approaches. Moreover, there remains a limited progression of theoretical advancements in SFD, with purposeful engagement across disciplines and innovative developments still being underutilized. We conclude that if SFD scholars remain within their disciplinary silos and do not move towards a common interdisciplinary research understanding, the field will continue to suffer from confusing theorization processes with limited prospects for further academic advancement and practical development.

INTRODUCTION

Since the turn of the millennium, sport has increasingly been accepted by governmental and non-governmental actors as both a goal in its own right and a medium for achieving a variety of development goals. Sport’s recognition as a critical site for socialization (Coakley, 1998) and its reputation of being a low-cost and high-impact tool in achieving development goals has led to an increasing institutionalization of sport for development (SFD) within international relations and global development, flanked and funded by national and multilateral development agencies including the United Nations (UN), the Commonwealth Secretariat, and country-specific institutions such as the Norwegian or German Development Cooperation Agencies (Giulianotti et al., 2019; Kay & Dudfield, 2013). Although SFD initiatives have existed for decades, the field’s practical nature likely contributed to a delayed onset of specific research studies and wider scholarly engagement with the field (Darnell, 2012). In fact, there were only a handful of dedicated SFD publications available in the early 2000s and contributions to scientific journals only started to increase more significantly from around 2008 onwards (Schulenkorf, 2017; Schulenkorf et al., 2016). By 2013, the number of annual publications amounted to over 100 articles – a remarkable development that was accompanied by the establishment of the open-access Journal of Sport for Development (JSFD) as well as publication and dissemination opportunities on the SFD online platform sportanddev.org. Taken together, these initiatives assisted in providing much-needed accessibility and transparency regarding evaluation and research approaches in SFD (Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Whitley et al., 2019b; Whitley et al., 2019a).

Given its widespread appeal, numerous theoretical foundations, approaches, designs, and methods have been used in SFD research. However, research endeavors and scholarly engagements have largely remained within their disciplinary silos. Disciplinary trends from sport sociology, sport management, public health, leisure and other disciplines have already been transferred to the SFD context, but interconnections and common perspectives – including transdisciplinary engagements – have thus far been neglected (Massey & Whitley, 2019; Siefken, 2022; Whitley et al., 2022). As a result, research to date has led to critical yet largely isolated and often under-used SFD-specific theories and concepts (Welty Peachey et al., 2021). Moreover, while the benefits of intersectoral or inter-disciplinary SFD have increasingly been recommended in academic scholarship or mapped in the form of brainstorming articles (Collison et al., 2019a; Delheye et al., 2020; Welty Peachey et al., 2021; Whitley et al., 2022), there remains a lack of clarity and common understanding across several domains, including the terminology that surrounds aspects of research and evaluation in SFD. Such a common understanding is critical for interdisciplinary research where the great diversity of parties involved – including observers (e.g., scholars), those observed (e.g., project and program implementers, non-governmental organizations), interested parties (e.g., donors, community), and influencers (e.g., national agencies, ministries) – should sing from the same hymn-sheet rather than remain with different and at times contradictory understandings of research approaches and associated terminology (Massey & Whitley, 2019).

Against this background, we conducted a review of publications focusing on research and evaluation in SFD to showcase the different types of research and evaluation studies that have been undertaken in the SFD field; how they have been conducted; and how different research terms have been used, understood and differentiated.

Our scoping study aimed to map the status quo of SFD research and evaluation and the associated terminology, and shed light on the shortcomings, development opportunities and future advancements in this critical space. In the following, we present the scholarly framework and methodological processes that underpin our study. In line with the two research questions, we then highlight and discuss key research findings and conclude with a call for action to define and unite common interdisciplinary research understandings in SFD.

Evaluation Research Framework

Evaluation research emerged as a distinct field of study in the mid-20th century, primarily in the United States of America. Its development can be attributed to the growing interest in assessing the impact and effectiveness of social programs and policies. Influenced by the fields of sociology, psychology, and public administration, evaluation research gained prominence during the 1960s and 1970s as a response to the growing demand for evidence-based approaches to inform decision-making and resource allocation (Marjanovic et al., 2009). In the 1960s, the American development agency USAID and a few larger United Nations organizations made first attempts to establish evaluation as an integral part of project and program management (Döring & Bortz, 2016). In Europe, the integration of evaluation into institutional structures and processes within the context of political systems, presented a main driver for the significant increase in practical evaluation studies, particularly in the context of growing development cooperation (Stockmann & Meyer, 2017). Since its inception, evaluation research has expanded globally and is now practiced across various disciplines and countries, shaping policy development and program implementation worldwide.

Most authors in evaluation research use the term ‘evaluation research’ synonymously with ‘scientific evaluation’ or in short ‘evaluation’ (Döring & Bortz, 2016; Rossi et al., 2004; Scriven, 2008; Vedung, 2000). Here, the common understanding is that evaluations “are assessments made on the basis of research findings in a scientific process by evaluation professionals qualified in social science” (Döring & Bortz, 2016, p. 977). As such, evaluation is part of applied social research and it features a whole range of social science theories, concepts and research methods (Stockmann, 2007). In the social and health sciences, program evaluation is likely the largest area of evaluation research which – due to its application-oriented nature – has the distinct ability of generating evidence-based knowledge for practical use (Rossi et al., 2004). This practical knowledge can then be used to optimize, steer, or legitimize programs, among other functions of evaluations (Stockmann, 2007). Due to its applied nature and the ability to advance practice in the field, evaluation research is of particular relevance and importance for SFD studies.

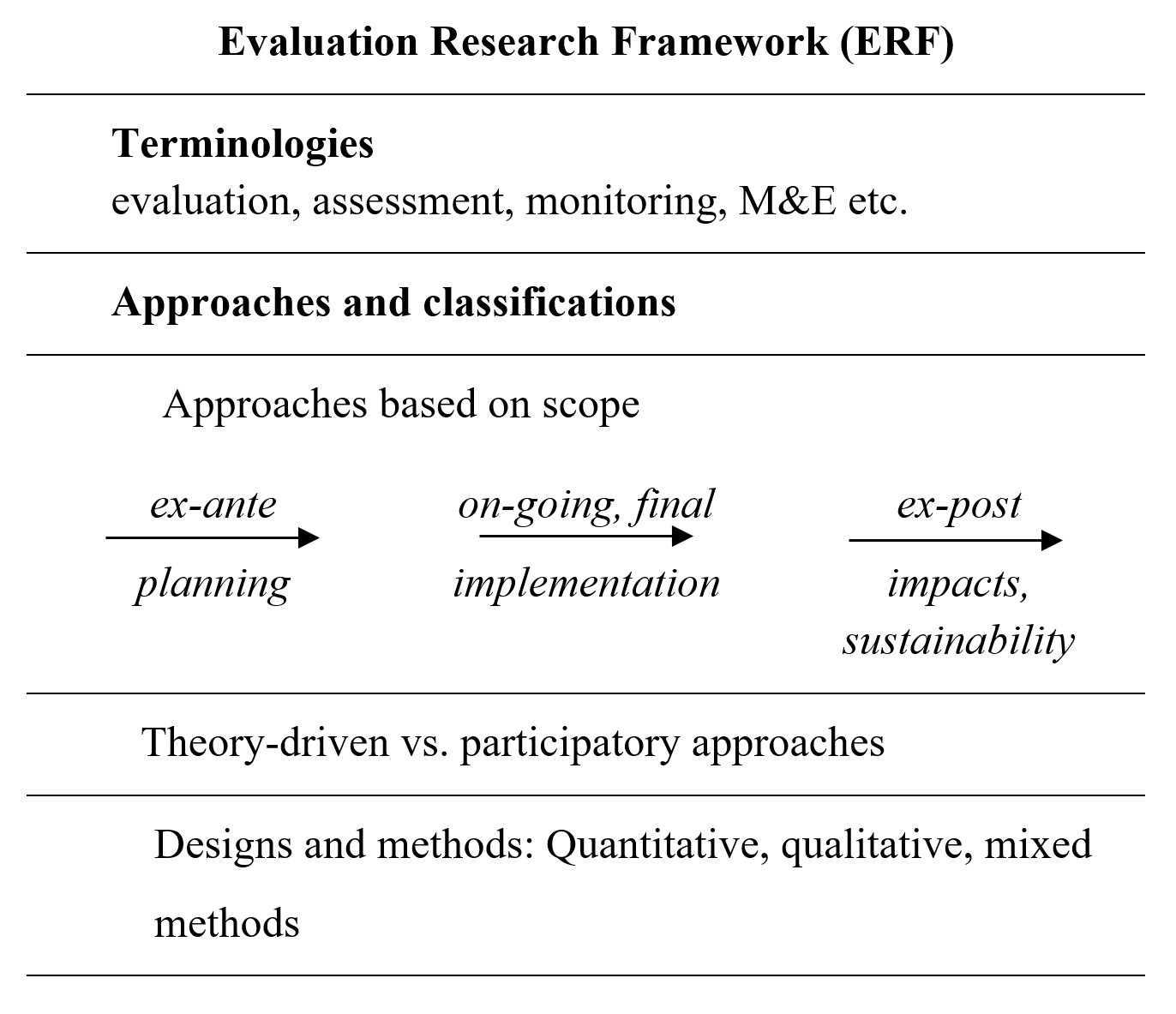

There are countless concepts, models, theories and approaches to evaluation across theory and practice, including directions for evaluation design and implementation. As such, different attempts have been made to classify evaluation concepts, models, theories, and paradigms based on their similarities and differences (Alkin & Christie, 2009; Rossi et al., 2004). Of particular relevance for the current study is Rabie’s (2014) classification system which brings together important and widely used concepts of evaluation research and presents a comprehensive yet clearly structured approach to evaluation that provides analytical rigor and compensates for some of the limitations of previous systems in use. Hence, in an attempt to explore the research and evaluation activities in the field of SFD, Rabie’s (2014) work underpinned the design of the newly proposed Evaluation Research Framework (ERF) which was used as a deductive framework for this review study.

Figure 1 – The Evaluation Research Framework (ERF) and its Categories

The ERF is based on previous work by the first author (Bauer, 2022) and contains three different yet interrelated domains: First, the terminologies focus on the understanding and interplay of definitions regarding the terms used in this space, including monitoring, evaluation and research. According to Vedung (2000, p. 124) “the key difference between evaluation research and fundamental research is that the former is intended for use”. It is therefore more prescribed and less free than fundamental or basic research, which can strive for knowledge without a specific pre-defined purpose. In addition, there are many other terms used instead of, combined with, or in conjunction with evaluation, such as appraisal, assessment, auditing, (financial) controlling or monitoring (monitoring and evaluation, in short: M&E). Finally, recent trends have also emphasized evaluation and value functions combined with research and monitoring, such as ‘learning’ or ‘accountability’ (e.g., MEL, MERL or MEAL). Even though the activities associated with these terms differ from those of evaluation, the dividing lines are often blurred (Scriven, 2008).

As the second domain, the framework captures and systematizes the various approaches and classifications, including concepts, models, theories, and approaches. It follows a three-tiered pragmatic approach: The first sub-category helps to delineate what will be evaluated and focuses on the scope of a study. For instance, the evaluation may be very broad and includes comprehensive evaluands (e.g., strategies, systems, sectors, interventions in their entirety) which are covered by different forms of reviews (evaluation synthesis, systematic review, meta-evaluation). Alternatively, it may focus on one particular aspect or phase of an intervention, which can differ in timing and its objective: For example, ex-ante evaluations may operate as feasibility or baseline studies before a project starts; on-going evaluations can be used for process evaluations; and final evaluations may feature at the end of a project for the assessment of direct goal achievements or as ex-post studies to evaluate program impacts and sustainability (Rabie, 2014; Rossi et al., 2004; Stockmann, 2007).

The approaches of the second sub-category can help to clarify the purpose of the evaluation. Here, theory-based approaches aim to increase knowledge about the object of study and explain causalities, e.g., by using a logical model/logical framework, which can make statements about whether pre-formulated indicators are achieved in terms of its resources (inputs), performance (outputs), effects at the target group level (outcomes) or effects at the societal level (impacts) (Kurz & Kubek, 2016; Oberndörfer et al., 2010; Scriven, 2008). Meanwhile, participatory approaches aim to actively involve stakeholders in evaluations, to empower their evaluation capacities, and to create a common understanding (Rabie, 2014).

The third and final sub-category focuses on designs and methods and answers the question of how a specific program is assessed or evaluated. Specifically, it determines if quantitative (quasi-experimental or experimental designs like Randomized Controlled Trials – RCTs), qualitative (e.g., participatory action research) or mixed-methods designs are used (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Rabie, 2014; Scriven, 2008). Taken together, the ERF allows scholars to examine research and evaluation thoroughly and holistically. Specifically, it determines how terminology is used; identifies the attribution and intention of a study (basic research or evaluation research); establishes the extent to which it is comprehensive or partial (scope); assesses whether the purpose is theory-driven or participatory; and understands the way research and evaluation is carried out (design and method).

METHODOLOGY

Scientific review studies come in a number of different shapes and sizes or, as Grant and Booth (2009) outlined, there is a large variety of research types and associated methodologies for researchers to choose from. For this paper, in which we aimed to review and map evaluation and research practices and debates in the field of SFD, a scoping review approach was carried out. Scoping reviews have gained prominence in the SFD space over the past 10 years; specifically, previous studies have focused on SFD research within Aboriginal communities (Gardam et al., 2017); have examined innovation approaches such as Design Thinking in SFD practice (Joachim et al., 2020); or have mapped SFD evidence specific to the African continent (Langer, 2015). The scoping review seemed the most appropriate type for this study as it aims to summarize and disseminate findings, clarify key definitions in the literature, examine how research is conducted on a certain field and identify research or knowledge gaps in existing literature – regardless of differences in publication types and without the need to account for research quality per se (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018). As such, it presents a significant first step in our endeavor to better understand the research and evaluation space in SFD and it may provide a critical stepping stone for more advanced and comprehensive systematic reviews that focus on quality and rigor in the future. To conduct a scoping study, Arksey and O’Malley (2005) recommend five critical steps which have also guided our investigation.

Identification of research questions

In the first stage of a scoping study, it is recommended to use broad search parameters to ensure that no relevant studies are overlooked (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). To avoid an unwieldy number of publications, we used the ERF model as a theoretical-conceptual perspective based on evaluation research (Bauer, 2022). This allowed us to specifically address two interrelated research questions.

- How are research, evaluation and other related terms defined and understood in the SFD context?

- How are research and evaluation activities carried out, i.e., which different approaches – including designs and methods – are used?

Identification and selection of relevant publications

To identify the literature that answers the research questions, a comprehensive search of databases and journals was conducted. As suggested by Arksey & O’Malley (2005), we employed flexible strategies that involved searching for relevant publications across various sources, including electronic databases, reference lists, hand-searching key journals, and relevant organizations and conferences. In line with previous review studies, a variety of thematically relevant and multidisciplinary databases and catalogues were used, including sport-focused databases, general academic search engines, and a range of topic-specific journals (see Table 1); moreover, specific journals that had previously been identified as leading outlets for SFD work in Schulenkorf et al.’s (2016) comprehensive integrative review were included. Finally, the search was complemented with relevant items from various supplementary materials including academic books internet sources, journal articles, reports, theses and grey literature (e.g., documents of the United Nations or Commonwealth Secretariat).

For the different sources, a combination of search terms connecting evaluation, research and SFD were used in English and German language. Specifically, as the review formed part of a larger research project on SFD in the context of German development cooperation, German search terms and literature were used in addition to the otherwise predominant English vocabulary and publications. Overall, the following search strings were used: evaluation, research, Forschung, Methode(n)/method(s) as well as the combined terms sport + development, “Sport for Development”, “Sport für Entwicklung”, Sportförderung. Table 1 presents the search area and bibliographic accesses used in addition to the search terms.

Table 1 – Overview of Search Terms, Area and Bibliographic Accesses

| Search Terms | English: (“evaluation” OR “research” OR “method*”) AND (“Sport for development” OR “sport” AND “development”)German: (“Evaluation” OR “Forschung” OR “Methode*”) AND (“Sport für Entwicklung” OR “Sportförderung”) |

| Search Area | Title, abstract, full text |

| Bibliographic accesses | Catalogs and databases: · Google Scholar, Google Books

· Online Catalog “ZB Sport“ German Sport University Cologne · SURF – the Sports information portal of the Federal Institute for Sports Science (BiSp) including different databases · Spolit – database including sports-related articles from journals and anthologies · Digital Library German Sport University Cologne · Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) Relevant Journals: · European Journal for Sport and Society (ISSN 1613-8171) · International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics (ISSN 1940-6940) · International Review for the Sociology of Sport (ISSN 1012-6902) · Journal of Sport and Social Issues (ISSN 0193-7235) · Journal of Sport for Development (open access): https://jsfd.org/ · Journal of Sport Management (ISSN 0888-4773) · Sport, Education and Society (ISSN 1357-3322) · Sport Management Review (ISSN 1441-3523) · Sport in Society (ISSN 1743-0445) · Sociology of Sport Journal (ISSN: 0741-1235) · Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health (ISSN 2159-676X) |

The initial focus on the title search made sure that results would include documents with a clear focus on research and evaluation in the field of SFD, including discussions on methodological research approaches such as M&E and qualitative methods. In other words, the intent was to capture articles, reviews, conceptual papers or texts with a distinct research focus, rather than single empirical studies that merely mentioned the term research as part of their analysis or structure.

The publication types included monographs, edited books, book chapters, internet sources, journal articles, reports, grey literature as well as PhD and Masters theses in English and German published between 2006 and March 2022. The year 2006 was selected as the earliest date because it was when the first manual focusing on M&E in the context of SFD was published (Coalter, 2006). This manual resulted from a workshop initiated by UNICEF and attended by key scholars, politicians, development agencies, and practitioners (Burnett, 2015). Furthermore, to complement the automated findings of the journal and database search, the reference lists of included documents were manually scanned to identify further potentially relevant materials (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Herold et al., 2020).

From a process perspective, two authors eliminated duplicate articles and analyzed all available abstracts according to the key elements identified in the ERF that guided this study. All abstracts were read independently by the two authors to enhance validity and to ensure inter-coder reliability, the third researcher became involved in case of disagreement. In total, 204 relevant publications and internet documents were identified and subsequently charted. Table 2 summarizes the sampling results according to publication types.

Table 2 – List of Analyzed SFD Publications

| Type of publication | Numbers |

| Monographs | 16 |

| Edited volumes | 15 |

| Book chapters | 43 |

| Journal articles | 101 |

| Grey literature | 18 |

| Internet sites | 3 |

| White papers (University publications) | 8 |

| Total | 204 |

Charting the publications

Based on the total sample identified, the material was sifted, charted and sorted according to the different key elements identified in the ERF (see Figure 1). In particular, special attention was paid to the terminology used (e.g., evaluation, monitoring, etc.) as well as the various approaches and classifications mentioned or employed (e.g., scope of studies, designs, methods, etc.). The ERF categories were used to record the information descriptively. As an example, Kay’s (2012) article on monitoring and evaluation in SFD partnerships contains information about specific terminology and approaches. She clearly distinguishes between M&E and research and does not endorse logical models as approaches.

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

As the information from the publications were chartered according to the ERF-categories, also the findings are structured and presented in accordance with the categories outlined in the ERF and the research questions listed above. First, the different understandings and interplays of terminologies within the realm of SFD research and evaluation are presented. Subsequently, a discussion of the various approaches and classifications employed in the SFD context is provided.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Terminologies: Imprecisions in understanding, application and interplay

Out of our total sample of 204 publications, 21 specifically related to terminologies used in SFD research. Across these documents, the terms research, evaluation, M&E and more recently also MEL (Monitoring, Evaluation, Learning) or MERL (Monitoring, Evaluation, Research, Learning) are used with a wide range of variations and are often employed interchangeably. In short, there is no clear conceptual demarcation. ‘Conducting research’ is often equated with M&E activities, which inevitably leads to an undifferentiated discourse (Kay, 2012). Here, the rather simplistic merger of the terms monitoring and evaluation into a single entity is problematic, as the two research functions require specific approaches as they serve different aspects: “As they pose and respond to different types of questions, it is evident that monitoring and […] evaluation […] require different tools, different skills, different strategies and ideally different personnel“ (Kaufman et al., 2014, p. 177).

Numerous authors critically note that even well-established SFD scholars tend to equate research with program evaluation and they emphasize the need for a clear differentiation (Jeanes & Lindsey, 2014; Welty Peachey & Cohen, 2015). For Jeanes and Lindsey (2014, p. 199), M&E should be considered a “processes of research”. They see the distinction in the fact that M&E is mainly used in the program context and aims at optimization, while research goes beyond that. However, Whitley et al. (2020, p. 22) note that “evaluation and research are not mutually exclusive, and there are arguments that evaluation is a subset of research (and vice versa)”. Collison et al. (2019a, p. 6) concur that research simply cannot be separated from M&E processes:

We would argue that the assumption that research necessarily informs, guides, influences or even constructs M&E frameworks or evidence is misguided. Progressive research methodologies focused on M&E, for example participatory action research, may well serve the dual purpose of knowledge production while producing and assisting with the formal process of evidencing and reporting, but the relationship between these processes requires ongoing negotiation and reflexivity.

Overall, this review reveals that the current incoherence in the SFD research field stems from the imprecisions in the use of terminology and concepts. The absence of clarity concerning research, evaluation, and M&E terminologies inevitably leads to a variety of debates in SFD research, including the role of researchers (who carries out the research and under which conditions?), methodological procedures (which designs and methods are best suited?) and the overall objective of the research (is it merely about generating new knowledge, about making strategic decisions or about receiving funding?).

A starting point for addressing imprecision in the use of terminology and related discussions would be the establishment of a shared vocabulary with the intention of ‘finding a common language’ (Barisch-Fritz & Volk, 2016). The benefit of such a vocabulary – particularly in the context of interdisciplinary research – is the ability to overcome obstacles by creating a unified language based on mutual understanding and effective dialogue among researchers from a range of disciplines. However, achieving a shared understanding requires acknowledging and including external expertise from a variety of areas. Moreover, given the potpourri of approaches taken by researchers – including fundamental research, evaluation research, or evaluation based on monitored information, and the different objectives and strategies in place – active collaboration and clear communication are required to achieve overall consensus.

Within the described debates and underpinned by the results of our study, there remains a regrettable lack of acknowledgement and inclusion of traditional debates from the social sciences and development studies. In fact, it seems important to consider multi-perspective considerations, such as critical voices of – and relations between – researchers, evaluators, commissioners and donor organizations, to find some common ground. Instead, SFD is as heavily influenced by hegemonic discourses, particularly in relation to the concept of development. In fact, it is widely acknowledged that the conceptualization of development presents one of the foremost challenges in the field of SFD (Hartmann & Kwauk, 2011). Accordingly, the field of SFD has encountered similar debates and policy challenges to those reported in wider development studies (Darnell & Black, 2011). Overall, it is suggested that unless the SFD research community addresses the described ambiguities and establishes crucial distinctions and a common language through active engagement and deliberation, progress towards terminological and conceptual clarity will be difficult to achieve.

Approaches and classifications: Many use what they know, few use what is established

Before the different sub-categories from the ERF are discussed (approaches based on scope, theory-driven and participatory approaches, designs and methods), general theorization processes in SFD research are highlighted first. This is done to provide the wider context and to ‘couch’ the applied findings related to approaches and classifications. Due to their importance in SFD research, the aspects of impacts and sustainability – which from an evaluation-theoretical perspective are subject of ex-post evaluations – are considered separately.

The theorization of SFD

Our scoping study identified 127 publications that engaged with aspects of theorization in SFD. Our review revealed that a lack of a theoretical foundation for research in the field of SFD was an early warning raised by numerous authors and that over the years, the demand for its establishment and the call for connectivity to other disciplines has only intensified (e.g., Coalter, 2013b; Darnell et al., 2019; Lyras & Welty Peachey, 2011; Massey & Whitley, 2019; Siefken, 2022; Welty Peachey & Cohen, 2015; Zanotti & Stephenson, 2019). Despite a stated lack of theoretical grounding and the scholarly verdict that “much work remains to be done” (Zanotti & Stephenson, 2019, p. 172), it should be noted that a number of significant theoretical and conceptual developments have taken place over the past decade (Darnell et al., 2019; Massey & Whitley, 2019; Schulenkorf et al., 2016). Specifically, the contributions in the Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (Collison et al., 2019b), as well as Welty Peachey et al.’s (2021) meta-analysis of theoretical advances in SFD illustrate the research community’s willingness and associated attempts to develop, employ and advance theoretical approaches.

Given the need to advance theoretical and conceptual thinking in SFD, a number of studies have employed a distinct sport-focused model of theoretical framing. Here, Welty Peachey et al. (2021) have identified the Sport for Development Theory (SFDT) (Lyras & Welty Peachey, 2011), the S4D Framework (Schulenkorf, 2012), Sugden’s Ripple Effect Model (2014), Coalter’s Program Theory (2013b) and Schulenkorf and Siefken’s (2019) Sport-for-Health Model as relevant examples. However, to date, most of these are hardly used to guide or support other studies which speaks to the relative infancy of SFD theory and the need to do more and better in an attempt to truly legitimize the field (Welty Peachey et al., 2021).

Meanwhile, where SFD studies have been underpinned by a derivate model of theoretical framing (see Chalip, 2006), the concepts of social capital and Positive Youth Development (PYD) theories have most commonly been employed in the context of SFD (Schulenkorf et al., 2016). However, despite their popularity, Darnell, Chawansky and colleagues (2018, pp. 138-139) describe these approaches as “relatively neutral” and “apolitical” and are calling for more critical SFD research that uses politicizing approaches (e.g., postcolonial or feminist), including those “that draw attention to the roots of inequality”.

As part of this development towards critical scholarship, academics from different disciplinary backgrounds have started to compile their varied theoretical approaches and brainstorm possibilities for transdisciplinary research in SFD. Here, a special issue in the journal Social Inclusion has opened transdisciplinary and intersectoral perspectives by providing a selection of articles that bring together various disciplinary streams (Delheye et al., 2020). Moreover, a recent journal article in JSFD has described selected disciplinary trends from the fields of sport sociology, social anthropology, sport management, public health, leisure, sport pedagogy, and sport psychology and provided critical avenues for transdisciplinary engagement (Delheye et al., 2020). Further, Siefken et al. (2022) emphasized the necessity to connect physical activity research with SFD, as highlighted in their recently published edited volume addressing opportunities and challenges in low- and middle-income countries. The call for cross-disciplinary and interdisciplinary work has been made. The integration of these perspectives certainly provides first important steps towards interdisciplinarity modifiable; however, thus far the selection of viewpoints has largely been based on the research backgrounds of the contributing authors of the articles published and a concerted effort to include all disciplines of the SFD field is yet to be realized.

In order to foster true interdisciplinarity, it is essential to ‘identify shared problem perspectives’ (Barisch-Fritz & Volk, 2016). Here, Whitley et al. (2022, p. 9) emphasize that common interests between different disciplines include life skills development and transfer, as well as the parallels between PYD theory and “the anthropological examination of youth in SFD”. Furthermore, the wide-ranging orientation of SFD organizations towards the Sustainable Development Goals and related issues such as social inequality, environment, safeguarding, refugees, and social entrepreneurship (Giulianotti et al., 2019) could form common denominators.

Approaches based on scope

The scope of research studies varies considerably across academic domains and our review revealed that this is no different in the SFD space. Overall, we identified 18 publications related to scope-based approaches. Specifically, after an initial focus on micro-level case studies and first attempts to ‘map the field’ (e.g., Hillyer et al., 2011), SFD researchers have now embarked on the next level of systematic reviews and assessments. In this context, Darnell, Chawansky and colleagues (2018, p. 134) call it “a marker of the field’s maturation” that more and more researchers are conducting and publishing comprehensive systematic reviews and meta-analyses, in this case based on available SFD literature (Holt et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2017; Langer, 2015; Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Svensson & Woods, 2017; Welty Peachey et al., 2021; Whitley et al., 2019a).

Whilst these review studies have contributed significantly towards a broad picture of the SFD overall research landscape, the findings show that there remains a lack of specific meta-evaluations that examine the quality of studies and evaluations, including those that focus on specific themes or domains such as impact and sustainability – issues that are considered critical in SFD work and which are discussed in more detail later in this article. Moreover, our scoping analysis revealed that to date only one systematic review has examined the methodological quality of studies in detail (Darnell et al., 2019) and can therefore be classified as a meta-evaluation in the context of the ERF. To further support SFD’s ‘maturation’ process, it seems essential that further studies with a wider scope and deeper focus – in particularly meta-evaluations that explore and improve the quality of SFD studies – will be undertaken in future research.

Our review further shows that most SFD studies take place during project implementation (“ongoing”) or right at the end of the project (“final”) when research funding is often still available. No studies could be identified that explicitly focus on the planning (“ex-ante”) or post project/program phase (“ex-post”), highlighting the persistent lack of focus on researching long-term impacts and aspects of sustainability. Both these aspects are discussed in more detail at the end of this section.

Theory-driven vs. participatory approaches

Overall, the scoping study identified 47 publications that discussed theory-driven or participatory approaches. Despite their ability to demonstrate the causal relationship between projects inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts (Kurz & Kubek, 2016), to date, only few SFD organizations can be credited for – or have proven to employ – theory-driven approaches such as logic models to underpin their operations (Whitley et al., 2019b). However, there seems to be a growing interest and increased understanding in this critical space. Most notably, the theory-driven Results Based Management (RBM) approach – which has been widely used in general development cooperation work since the 1990s (Binnendijk, 2000) – is part of the most recently published SFD-guidelines of the Commonwealth Secretariat (2019). However, the findings show that overall attitudes towards theory-driven logic models still differ among SFD researchers: on the one hand, critics describe them as being overly output-oriented, linear and rigid, and largely top-down or donor-imposed (Kay, 2012; Lindsey & Grattan, 2012; Spaaij et al., 2018). On the other hand, according to proponents, they represent flexible frameworks “that are participative, collaborative, iterative, and developmental” (Whitley et al., 2020, p. 23). Preti (2012) points out that criticism in this regard must distinguish between the general approach (i.e., project planning including problem analysis, development of objectives and indicators, identification of risks and assumptions) and the logframe matrices used in programs summarizing the main elements. The latter tend to have numerous shortcomings: They often remain “inflexible blueprints” in that they are established before a project begins, ‘imposed’ on a project, and therefore limited in their ability to make regular adjustments during the course of the project. Hence, Whitley et al. (2020, p. 24) advocate for active support of SFD organizations “in setting up their own […] frameworks […] or adapting/adopting existing frameworks” that hold credibility and provide legitimacy to funders, align with national policy priorities, and enable organizational development and learning.

Meanwhile, our review revealed that numerous researchers are also calling for more participatory, culturally and context-sensitive approaches, designs, and methods to holistically understand complex development dynamics, including M&E processes (Burnett, 2015; Collison & Marchesseault, 2018; Darnell, Chawansky, et al., 2018; Darnell et al., 2016; Kay, 2012; Sherry et al., 2017). In general, participatory approaches such as Participatory Action Research (PAR) have been used on a regular basis when analyzing SFD projects and programs (Burnett, 2015; Sherry et al., 2017). Furthermore, participatory approaches are modifiable into guiding study models or frameworks, for example in the form of the Sport for Development Impact Assessment Tool (SDIAT) (Burnett & Hollander, 2007), Participatory Social Interaction Research (PSIR) (Collison & Marchesseault, 2018), Post-colonial-feminist Participatory Action Research (PFPAR) (Hayhurst et al., 2015) and the qualitative Sport in development settings (SPIDS) framework – where reflection and reflexivity are given a special role in sport and development scholarship (Schulenkorf et al., 2020). The latter comes on the back of research by Spaaij and colleagues (2018) who examined a variety of participatory SFD studies which showed particular deficits in reflection and critical questioning of the researchers’ roles (reflexivity) – an area that has previously been highlighted as a critical yet understudied space in SFD research (Darnell, Giulianotti, et al., 2018).

Designs and methods

In our analysis, we identified 23 publications related to the designs and methods used in the field of SFD. In their integrative review of SFD scholarship, Schulenkorf et al. (2016, p. 35) identified a “potpourri of research approaches and methods” with more qualitative designs being used overall and fewer quantitative or mixed methods designs. For data collection, mainly traditional qualitative methods have been used, including observations, interviews, and document analyses (Schulenkorf et al., 2016). The benefits of innovative, creative, culturally appropriate, and technologically savvy designs and methods are only starting to be realized. Specifically, methods that use innovative media technologies, such as videos, iPads or social media, as well as diverse creative and flexible survey types such as drawings, poems, stories of change or participatory mapping have been suggested as critical elements for methodological advancement (Darnell et al., 2016; Luguetti et al., 2022; Preti, 2012; Schulenkorf et al., 2016; Sherry et al., 2017).

It is logical that a field of research – which is shaped by researchers from various disciplines with different theoretical approaches and educational backgrounds – cannot show unity with regard to research paradigms or methodological procedures. However, the review uncovered that in the specific SFD context, more seems to be at play. At first glance, it may be seen as merely a methodological dispute that takes place in empirical social research, i.e., a split between supporters of the quantitative and qualitative ‘camps’. On closer examination, however, the dispute goes beyond the discussion about the ‘right’ methodological approaches and leads to fundamental debates about power and ownership, including top-down and bottom-up (research) approaches in development work. Here, discussion topics go beyond the value and rigor of scientific traditions (positivist vs. interpretivist, constructivist or critical paradigms) and extend to the research perspective of researchers from the Global North (‘colonizer’) evaluating projects and organizations in the Global South; the conceptualization and definition of ‘development’ in general; and the production of new knowledge and localized, Indigenous voices in particular (Hartmann & Kwauk, 2011; Whitley et al., 2020).

In this context, critics often question positivist approaches and are concerned that associated methods and top-down procedures (external researchers assessing local projects without local contributions) reinforce neo-colonial power structures and hegemonic systems while suppressing local knowledge production (Kay, 2012; Lindsey & Grattan, 2012). Opposing voices portray this as a critique of militant “liberation methodologists” (Coalter, 2013a, p. 38) who defy reality and who seek to put neo-colonial attitudes on par with positivist methodological approaches whilst avoiding the much-needed defining and measuring of outcomes and impacts (Whitley et al., 2020). Overall, the repartee is sometimes more, sometimes less extensive across all kinds of publications (e.g., Coalter, 2013a; Darnell et al., 2016; Kay 2012; Lindsey & Grattan, 2012) which leads Massey and Whitley (2019, p. 177) to suggest that to meaningfully address this issue, it would be better to have a more nuanced debate on methodology: “Rather than lay blanket critiques across different research paradigms and epistemologies, there is a need to discuss higher levels of sophistication in both instrumental/positivist (i.e., quantitative) and descriptive/critical (i.e., qualitative) SDP research”. In building on this recommendation, researchers are now increasingly trying to bridge the gap between the two main streams. In other words, in an attempt to avoid an ‘either-or’ perspective scholars have started to engage in more nuanced discussions for more inclusive theoretical and methodological solutions (Whitley et al., 2020). Here, the previously discussed use of theoretical approaches that focus on systemic interrelationships – such as the concept of policy coherence (Lindsey & Darby, 2019) or actor-network theory (Darnell, Giulianotti, et al., 2018) – could be valid ways forward.

Impacts and sustainability

Overall, we identified 44 publications related to impacts and sustainability aspects. Due to its label as a “low-cost, high-impact tool” for international development (Kay & Dudfield, 2013, p. 13), sport is – perhaps more than any other tool – under pressure to prove what it can contribute to various development outcomes (Levermore, 2011). Hence, impact studies have become a popular approach to justify sport-based development programs. However, critical voices have objected the instrumentalization of impact studies and have accused both implementers and donors to mainly use them as a vehicle that legitimizes their investments and shows alleged “proof” of the effects of their programs (Burnett, 2015; Preti, 2012; Schulenkorf et al., 2016).

The difficulty of tracking, measuring, or even isolating the ‘sport-made’ impacts and thus closing the attribution gap has long been recognized in the SFD domain (Coalter, 2013b, 2013a; Levermore, 2011). In fact, in some cases attempts to measure sport-specific contributions have been declared as impossible (Lindsey & Chapman, 2017). While there is agreement in regards to the criticality of making impacts ’visible’ (Commonwealth Secretariat, 2019), impact attributions are therefore formulated more ’cautiously’ (Kay & Dudfield, 2013; Schulenkorf, 2017) and scholars mainly talk about (often indirect) contributions to specific development objectives or the SDGs more broadly (Lindsey & Chapman, 2017). Perhaps the exaggeration of sport being an “all-purpose social vaccine” (Coalter, 2013a, p. 55) has finally been demystified, or – as Schulenkorf (2017, p. 244) has put it – “it seems that the SFD community has largely cured its own biggest social ill; namely, the simplistic view that sport, and even SFD, automatically leads to positive social, cultural, educational, health-related and/or economic development”.

Popular across the natural sciences, RCTs – also known as the ‘gold standard’ of evaluations – are supposed to close attribution gaps and isolate the effects of an intervention by comparing changes of randomly selected intervention and control groups (Mueller & Albrecht, 2016; Scriven, 2008). In the SFD context, this rigorous yet complex design is rarely feasible. Although there is an increasing demand for robust SFD study designs (Darnell et al., 2019; Kaufman et al., 2014; Lindsey & Darby, 2019; Massey & Whitley, 2019), researchers are weary that in addition to methodological and practical challenges of RCT trials – including limited opportunities for control groups – ethical challenges remain. Specifically, interventions have to be controlled and standardized in order to explain causal mechanisms in a way that may neglect the specific needs and concerns of vulnerable populations, including individual children (Mueller & Albrecht, 2016). This also speaks to a wider issue of quantitative impact studies which tend to neglect the social context of programs. Here, internal and external factors and their influence on an intervention’s effects are often not appropriately considered or underestimated. Associated social, managerial and political factors such as internal organizational structures, staff rotations, project durations as well as political systems and cultural peculiarities do have a great influence on the impacts and outcomes of a project or program, and they tend to be largely ignored in RCT assessments (Lindsey, 2017; Stockmann, 2006).

While the absence of RCT studies can be explained in part by the factors above, the limited use of ex-post evaluations – meaning studies which are set-up after the completion of a project in order to assess long-term effects (impacts) and sustainability – remains a surprise, specifically as there are also readily available theoretical models for impact evaluation in evaluation research (Oberndörfer et al., 2010). Aspects of sustainability (in terms of durability) of donor-dependent SFD projects have previously been questioned and criticized (Lindsey, 2017). Furthermore, (long-term) ecological impacts have been discussed in the context of sport and environmental issues (Darnell, 2019) and ‘thought about’ in the context of the S4D Framework (Schulenkorf, 2012). However, the issue of sustainability per se has received little explicit practical attention in SFD evaluations and research. In fact, with the notable exception of Lindsey’s (2008) conceptual work, suitable theoretical approaches or assessment frameworks have not yet been developed (Sherry & Osborne, 2019). As the findings of the category “approaches based on scope” have already shown, no studies could be identified that explicitly focus on the post project/program phase (“ex-post”), highlighting the persistent lack of focus on researching long-term effects and aspects of sustainability. Again, these omissions provide a worrying status quo as it has long been argued that conducting more ex-post evaluations on completed projects is crucial to assess processes (e.g., the influence of project planning, management, and follow-up on sustainability), sustainability (i.e., the fate of projects after funding), and overall SFD impact (i.e., intended and unintended effects, identify factors of success and failure).

CONCLUSION

The present scoping study aimed to review and subsequently advance our understanding of research and evaluation in SFD. The study was underpinned by the newly designed ERF which has been introduced to the SFD space as a conceptual guide that provides an appropriate lens from which to conduct evaluation research. In SFD circles, evaluation research has struggled to receive the explicit attention it deserves and as such, the ERF framework makes an important conceptual contribution for the sector and beyond, as it draws attention to evaluation-relevant aspects, such as the timing of studies (ex-ante, on-going, ex-post) or the objectives and function of studies.

Against this background, our study uncovered several key findings and implications. Firstly, by examining SFD research through the lens of evaluation research, it became apparent that there is a lack of clarity surrounding research, evaluation and M&E terminologies resulting in imprecise study foci and associated debates around research objectives and researcher roles. In other words, our review uncovered one critical source of misunderstandings and misalignment amongst researchers, and a potential obstacle to stronger interdisciplinary engagement in research. Secondly, concerning approaches employed in SFD generally, our review highlights a limited progression of theoretical advancements in SFD, with researchers from a wide range of disciplines merely relying on the approaches and concepts they already know. Purposeful engagement across disciplines and innovative developments for new theoretical concepts related to SFD are still underutilized, despite a number of promising avenues including systems approaches or sustainability concepts that deserve to be investigated further. Overall, the limited utilization of existing concepts and lack of interdisciplinary collaboration remains a challenge, despite recent efforts to bring together approaches from various disciplines.

On the basis of the findings – and in order to tackle identified challenges with an end-goal of shifting towards more interdisciplinary engagement in SFD – three steps are suggested as a way forward:

- Establishing effective communication strategies to create a shared language: The review reinforced the criticality of this first step. A clearer differentiation and communication of the type of research being conducted (e.g., basic research, evaluation research, research based on M&E) is necessary to establish mutual understanding. In this context, it is important to consider evaluation not just as a component of M&E, but also as a segment of applied social research that utilizes a broad range of social science theories, concepts and methods. One initial measure would be to create a cross-disciplinary SFD glossary that integrates evaluation and research elements. Another option could be for researchers to provide a clear description within studies of how the research – specifically studies with quantitative or mixed-methods designs – was undertaken and how this may have impacted the study, including categorizing the role of the researcher in relation to the study (‘reflexivity’).

- Examining neighboring fields to unify approaches and reconcile methods: By reviewing and summarizing approaches from different disciplines in the form of handbooks and brainstorming articles, researchers have started to examine the different disciplines connected to SFD. A critical next step would be to deepen the engagement with other fields of study and to identify further crucial theoretical elements for SFD, focusing on so far neglected but important theoretical models and approaches (e.g., concepts focusing on quality, impacts, sustainability and systems from development studies and evaluation research). However, instead of just imposing familiar theories stemming from their own disciplines, researchers should also engage in exploring some of the previously proposed SFD theories and concepts in order to assess their feasibility and applicability in different contexts. Such a sport-focused approach would allow for much needed critical engagement with SFD conceptualizations as well as opportunities for theoretical and methodological advancement ‘from within’ the discipline (see also Chalip, 2006; Welty Peachey et al., 2021). Taken together – and acknowledging the inherent complexity involved in combining or reconciling fields for interdisciplinary research – we argue the recommendation of ‘spreading out’ to other theoretical fields does not have to come at the expense of ‘diving deeper’ into existing SFD conceptualizations.

- Identifying shared perspectives and interests on problems: SFD scholars have already identified key development areas that are critical for future engagement and collaboration between organizations and researchers, such as social inequality, environmental issues, safeguarding, refugees and social entrepreneurship (Giulianotti et al., 2019). There is also a shared interest in different impact mechanisms and processes of SFD – i.e., explanations for why certain impacts and developments occur when using SFD (Whitley et al., 2022). These subjects form an opportune foundation for collaboration, as already realized by various scholarly initiatives, including webinars organized by the authors of “Moving beyond disciplinary silos: the potential for transdisciplinary research in Sport for Development”, led by Meredith Whitley in October 2022. As a consequence of this exchange amongst SFD researchers with diverse disciplinary backgrounds from across the globe, working groups were established to explore different SFD-relevant subjects, including ‘livelihoods’, ‘policy’, ‘system thinking and collective impact’, and ‘education, youth development and life skills’. With a first step towards shared perspectives now realized, it will be intriguing to observe if and how interdisciplinary contributions to SFD research will emerge from these working groups in the future.

Embarking on this suggested three-step approach necessitates resources and a shared commitment. Familiarizing oneself with the theoretical concepts of other fields, engaging in dialogues and debates, and gaining a comprehensive understanding require both willingness and availability. Regrettably, university structures often fall short in providing said resources, particularly to early-career scholars who often struggle with limited time and financial capabilities (Welty Peachey & Cohen, 2015). We conclude that evaluating SFD programs is complex for a multitude of inter-related reasons, including their multifaceted nature; their transdisciplinary approaches; and the diverse range of goals they aim to achieve. Addressing these challenges requires a collaborative approach that involves active engagement from researchers, practitioners, and the wider SFD community.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

The authors received no financial support for this article and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the scoping review.

Alkin, M., & Christie, C. (2009). An Evaluation Theory Tree. In M. Alkin (Ed.), Evaluation roots: Tracing theorists’ views and influences (pp. 13–65). Sage Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984157.n2

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Barisch-Fritz, B., & Volk, C. (2016). Übersicht zum Thema Interdisziplinarität und Sportwissenschaft. Ze-Phir, 23(2), 4–7. https://www.sportwissenschaft.de/fileadmin/pdf/Ze-phir-Ausgaben/23_2_Interdisziplinaritaet.pdf

Bauer, K. (2022). Zwischen Verwissenschaftlichung und Anwendungsorientierung: EvaluationsForschung im Kontext von Sport für Entwicklung [Dissertation]. Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln.

Binnendijk, A. (2000). Results Based Management in the Development Co-operation Agencies: A Review of Experiences: Background Report. Paris. OECD, DAC Working Party on Aid Evaluation. https://www.mfcr.cz/assets/cs/media/ODA_Pr-028_2000_Rizeni-podle-vysledku-v-agenturach-rozvojove-spoluprace-Prehled-praxe-Shrnuti.pdf

*Burnett, C. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On Sport for Development and Peace. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4-5), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214539695

*Burnett, C., & Hollander, W. J. (2007). The Sport-in-Development Impact Assessment Tool (S•DIAT). African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, June, 123–135.

Chalip, L. (2006). Toward a Distinctive Sport Management Discipline. Journal of Sport Management, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.20.1.1

Coakley, J. (1998). Sport in Society: Issues and Controversies (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education (ISE Editions).

*Coalter, F. (2013a). Sport for development: What game are we playing? Routledge.

*Coalter, F. (2013b). ‘There is loads of relationships here’: Developing a programme theory for sport-for-change programmes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(5), 594–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212446143

Coalter, F. (2006). Sport‐in‐Development. A Monitoring and Evaluation Manual. https://www.sportanddev.org/en/article/publication/sport-development-monitoring-and-evaluation-manual

*Collison, H., Darnell, S. C., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (2019a). Introduction. In H. Collison, S. C. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & P. D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 1-10). Routledge.

*Collison, H., Darnell, S. C., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (Eds.). (2019b). Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace. Routledge.

*Collison, H., & Marchesseault, D. (2018). Finding the missing voices of Sport for Development and Peace (SDP): using a ‘Participatory Social Interaction Research’ methodology and anthropological perspectives within African developing countries. Sport in Society, 21(2), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1179732

*Commonwealth Secretariat. (2019). Measuring the contribution of sport, physical education and physical activity to the Sustainable Development Goals: Toolkit and model indicators. Commonwealth Secretariat. London. https://thecommonwealth.org/sites/default/files/inline/Sport-SDGs-Indicator-Framework.pdf

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (Fifth Edition). Sage.

*Darnell, S. C. (2012). Sport for Development and Peace: A Critical Sociology. Bloomsbury Academic.

*Darnell, S. C. (2019). SDP and the Environment. In H. Collison, S. C. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & P. D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 396–405). Routledge.

*Darnell, S. C., & Black, D. R. (2011). Mainstreaming Sport into International Development Studies. Third World Quarterly, 32(3), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.573934

*Darnell, S. C., Chawansky, M., Marchesseault, D., Holmes, M., & Hayhurst, L. (2018). The State of Play: Critical sociological insights into recent ‘Sport for Development and Peace’ research. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216646762

*Darnell, S. C., Giulianotti, R., David Howe, P., & Collison, H. (2018). Re-Assembling Sport for Development and Peace Through Actor Network Theory: Insights from Kingston, Jamaica. Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2016-0159

*Darnell, S. C., Whitley, M. A., Camiré, M., Massey, W. V., Blom, L. C., Chawansky, M., Forde, S., & Hayden, L. (2019). Systematic Reviews of Sport for Development Literature: Managerial and Policy Implications. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2019.1671776

*Darnell, S. C., Whitley, M. A., & Massey, W. V. (2016). Changing methods and methods of change: reflections on qualitative research in Sport for Development and Peace. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(5), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1214618

*Delheye, P., Verkooijen, K., Parnell, D., Hayton, J., & Haudenhuyse, R. (2020). Sport for Development: Opening Transdisciplinary and Intersectoral Perspectives. Social Inclusion, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.17645/si.i152

Döring, N., & Bortz, J. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (5. vollständig überarbeitete, aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage). Springer-Lehrbuch. Springer.

Gardam, K., Giles, A., & Hayhurst, L. M. (2017). Sport for development for Aboriginal youth in Canada: A scoping review. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(8), 30-40. https://jsfd.org/2017/04/20/sport-for-development-for-aboriginal-youth-in-canada-a-scoping-review/

*Giulianotti, R., Coalter, F., Collison, H., & Darnell, S. C. (2019). Rethinking Sportland: A New Research Agenda for the Sport for Development and Peace Sector. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 43(6), 411–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519867590

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Herold, D. M., Breitbarth, T., Schulenkorf, N., & Kummer, S. (2020). Sport logistics research: Reviewing and line marking of a new field. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(2), 357-379. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2019-0066

*Hartmann, D., & Kwauk, C. (2011). Sport and Development. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 35(3), 284–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723511416986

*Hayhurst, L. M., Giles, A. R., & Radforth, W. M. (2015). ‘I want to come here to prove them wrong’: using a post-colonial feminist participatory action research (PFPAR) approach to studying sport, gender and development programmes for urban Indigenous young women. Sport in Society, 18(8), 952–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2014.997585

*Hillyer, S. J., Zahorsky, M., & Munroe, Amanda, Moran, Sarah. (2011). Sport & Peace: Mapping the Field. Georgetown University, M.A. Programme in Conflict Resolution. www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/finalreportsportandpeacemappingthefield.pdf

*Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., MacDonald, D., Strachan, L., & Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

*Jeanes, R., & Lindsey, I. (2014). Where’s the “Evidence”? Reflecting Monitoring and Evaluation within Sport-for-Development. In K. Young & C. Okada (Eds.), Research in the Sociology of Sport: v.8. Sport, Social Development and Peace (pp. 197–217). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Joachim, G., Schulenkorf, N., Schlenker, K., & Frawley, S. (2020). Design thinking and sport for development: Enhancing organizational innovation. Managing Sport and Leisure, 25(3), 175-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2019.1611471

*Jones, G. J., Edwards, M. B., Bocarro, J. N., Bunds, K. S., & Smith, J. W. (2017). An integrative review of sport-based youth development literature. Sport in Society, 20(1), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1124569

*Kaufman, Z. A., Rosenbauer, B. P., & Moore, G. (2014). Lessons learned from Monitoring and Evaluating Sport-for-Development Programmes in the Caribbean. In N. Schulenkorf & D. Adair (Eds.), Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives (pp. 173–193). Palgrave Macmillan.

*Kay, T. (2012). Accounting for legacy: monitoring and evaluation in sport in development relationships. Sport in Society, 15(6), 888–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.708289

*Kay, T., & Dudfield, O. (2013). The Commonwealth Guide to Advancing Development through Sport. Commonwealth Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.14217/9781848591431-en

Kurz, B., & Kubek, D. (2016). Social Impact Navigator. The practical guide for organizations targeting better results. Phineo.

*Langer, L. (2015). Sport for development – a systematic map of evidence from Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 46(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2014.989665

*Levermore, R. (2011). Evaluating sport-for-development. Progress in Development Studies, 11(4), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499341001100405

*Lindsey, I. (2008). Conceptualising sustainability in sports development. Leisure Studies, 27(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360802048886

*Lindsey, I. (2017). Governance in sport-for-development: Problems and possibilities of (not) learning from international development. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(7), 801–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215623460

*Lindsey, I., & Chapman, T. (2017). Enhancing the contribution of sport to the Sustainable Development Goals. Commonwealth Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.14217/9781848599598-en

*Lindsey, I., & Darby, P. (2019). Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the policy coherence? International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(7), 793–812. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217752651

*Lindsey, I., & Grattan, A. (2012). An ‘international movement’? Decentring sport-for-development within Zambian communities. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 4(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2011.627360

Luguetti, C., Singehebhuye, L., & Spaaij, R. (2022). ‘Stop mocking, start respecting’: an activist approach meets African Australian refugee-background young women in grassroots football. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(1), 119-136. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1879920

*Lyras, A., & Welty Peachey, J. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14(4), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

Marjanovic, S., Hanney, S., & Wooding, S. (2009). A historical reflection on research evaluation studies, their recurrent themes and challenges. Rand Europe, Technical Report. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR789.html

*Massey, W. V., & Whitley, M. A. (2019). SDP and Research Methods. In H. Collison, S. C. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & P. D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 175–184). Routledge.

Mueller, C.E., Albrecht, M. (2016). The Future of Impact Evaluation Is Rigorous and Theory-Driven. In: Stockmann, R., Meyer, W. (Eds.), The Future of Evaluation (pp. 283-293). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137376374_21

Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, Alexa, & Aromataris, A. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Oberndörfer, D., Hanf, T., & Weiland, H. (Eds.). (2010). Freiburger Beiträge zu Entwicklung und Politik: Vol. 36. Verfahren der Wirkungsanalyse: Ein Handbuch für die entwicklungspolitische Praxis. Arnold Bergstraesser Institut. https://zewo.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Verfahren_Wirkungsanalyse-letzte_Version.pdf

*Preti, D. (2012). Monitoring and Evaluation: Between the Claims and Reality. In K. Gilbert & W. Bennett (Eds.), Sport, Peace and Development (pp. 309–317). Common Ground Publishing. LLC.

Rabie, B. (2014). Evaluation Models, Theories and Paradigms. In F. Cloete, B. Rabie, & C. de Coning (Eds.), Evaluation Management in South Africa and Africa (First edition, pp. 116–151). SUN Media.

Rossi, P. H., Lipsey, M. W., & Freeman, H. E. (2004). Evaluation: A Systematic Approach (7. ed.). Sage.

*Schulenkorf, N. (2012). Sustainable community development through sport and events: A conceptual framework for Sport-for-Development projects. Sport Management Review, 15(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.06.001

*Schulenkorf, N. (2017). Managing sport-for-development: Reflections and outlook. Sport Management Review, 20(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.11.003

*Schulenkorf, N., Edwards, D., & Hergesell, A. (2020). Guiding qualitative inquiry in sport-for-development: The sport in development settings (SPIDS) research framework. Journal of Sport for Development, 8(14), 53–69. https://jsfd.org/2020/05/01/guiding-qualitative-inquiry-in-sport-for-development-the-sport-in-development-settings-spids-research-framework/

*Schulenkorf, N., Sherry, E., & Rowe, K. (2016). Sport for Development: An Integrated Literature Review. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0263

*Schulenkorf, N., & Siefken, K. (2019). Managing sport-for-development and healthy lifestyles: The sport-for-health model. Sport Management Review, 22(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.09.003

Scriven, M. (2008). Evaluation Thesaurus (4. Aufl.). Sage Publications.

*Sherry, E., & Osborne, A. (2019). SDP and Homelessness. In H. Collison, S. C. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & P. D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 374–384). Routledge.

*Sherry, E., Schulenkorf, N., Seal, E., Nicholson, M., & Hoye, R. (2017). Sport-for-development: Inclusive, reflexive, and meaningful research in low- and middle-income settings. Sport Management Review, 20(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.10.010

*Siefken, K. (2022). Calling out for Change Makers to Move Beyond Disciplinary Perspectives. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 19(8), 529–530. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2022-0361

*Siefken, K., Varela-Ramirez, A., Waqanivalu, T., & Schulenkorf, N. (Eds.). (2022). Routledge Research in Physical Activity and Health. Physical Activity in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Routledge.

*Spaaij, R., Schulenkorf, N., Jeanes, R., & Oxford, S. (2018). Participatory research in sport-for-development: Complexities, experiences and (missed) opportunities. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.05.003

Stockmann, R. (2006). Evaluation und Qualitätsentwicklung: Eine Grundlage für wirkungsorientiertes Qualitätsmanagement. Sozialwissenschaftliche Evaluationsforschung: Vol. 5. Waxmann.

Stockmann, R. (Ed.) (2007). Handbuch zur Evaluation: Eine praktische Handlungsanleitung: Vol. 6. Waxmann.

Stockmann, R., & Meyer, W. (2017). Evaluation in Deutschland: Woher sie kommt, wo sie steht, wohin sie geht. Zeitschrift Für Evaluation (ZfEv), 16(2), 57–110.

*Sugden, J. (2014). The Ripple Effect: Critical Pragmatism, Conflict Resolution and Peace Building through Sport in Deeply Divided Societies. In N. Schulenkorf & D. Adair (Eds.), Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives (pp. 79–98). Palgrave Macmillan.

*Svensson, P. G., & Woods, H. (2017). A systematic overview of sport for development and peace organizations. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9), 36–48. https://jsfd.org/2017/09/20/a-systematic-overview-of-sport-for-development-and-peace-organisations/

Vedung, E. (2000). Evaluation Research and Fundamental Research. In R. Stockmann (Ed.), Evaluationsforschung: Grundlagen und ausgewählte Forschungsfelder (pp. 103–126). Leske + Budrich.

*Welty Peachey, J., & Cohen, A. (2015). Reflections from scholars on barriers and strategies in sport-for-development research. Journal of Sport for Development, 3(4), 16–27. https://jsfd.org/2015/09/01/reflections-from-scholars-on-barriers-and-strategies-in-sport-for-development-research/

*Welty Peachey, J., Schulenkorf, N., & Hill, P. (2021). Sport-for-development: A comprehensive analysis of theoretical and conceptual advancements. Sport Management Review, 5(23), 783-796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.11.002

*Whitley, M. A., Collison, H., Wright, P. M., Darnell, S. C., Schulenkorf, N., Knee, E., Holt, N. L., & Richards, J. (2022). Moving beyond disciplinary silos: the potential for transdisciplinary research in Sport for Development. Journal of Sport for Development, 10(2), 1–22. https://jsfd.org/2022/06/01/moving-beyond-disciplinary-silos-the-potential-for-transdisciplinary-research-in-sport-for-development/

*Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., Camiré, M., Blom, L. C., Chawansky, M., Forde, S., Boutet, M., Borbee, A., & Darnell, S. C. (2019a). A systematic review of sport for development interventions across six global cities. Sport Management Review, 22(2), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.013

*Whitley, M. A., Farrell, K., Wolff, E. A., & Hillyer, S. J. (2019b). Sport for development and peace: Surveying actors in the field. Journal of Sport for Development, 7(12), 1–15. https://jsfd.org/2019/02/01/sport-for-development-and-peace-surveying-actors-in-the-field/

*Whitley, M. A., Fraser, A., Dudfield, O., Yarrow, P., & van der Merwe, N. (2020). Insights on the funding landscape for monitoring, evaluation and research in sport for development. Journal of Sport for Development, 8(14), 21-35. https://jsfd.org/2020/03/01/insights-on-the-funding-landscape-for-monitoring-evaluation-and-research-in-sport-for-development/

*Zanotti, L., & Stephenson, M. (2019). SDP and Social Theory. In H. Collison, S. C. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & P. D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 165–174). Routledge.