Sarah Zipp1 and Lombe Mwambwa2

1 Mount St. Mary’s University, United States

2 University of Lausanne, National Organisation for Women in Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation, Zambia

Citation:

Zipp, S. & Mwambwa, L. (2023). Menstrual Health Education in Sport for Development: A Case Study from Zambia. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Menstruation impacts people around the world, yet this topic is shrouded in taboo, undermining our ability to understand experiences of menstrual health and well-being. Research and activism on menstruation experiences in the Global South has grown dramatically in recent years. However, menstrual health research in the field of sport for development (SFD) is largely absent.

The purpose of this study was to better understand the lived experience of menstrual health amongst adolescent girls in SFD, the impact of menstrual health education through SFD and in what ways SFD might serve as a platform for menstrual health education. The participants took part in four lessons on menstrual health through the National Organisation for Women in Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation (NOWSPAR) of Zambia. These sessions included sport-based activities, menstrual health lessons, and journaling with adolescent participants (n=79). The adult facilitators (n=3) also completed journal exercises. The data yielded three key themes: (1) understanding and learning about the menstrual cycle; (2) pain, discomfort and coping with menstrual symptoms; and (3) stigma, fear and embarrassment surrounding menstruation. We conclude that menstrual stigma is a root cause to many of the challenges girls face and that SFD can be an impactful environment for menstrual health education.

MENSTRUAL HEALTH EDUCATION IN SPORT FOR DEVELOPMENT: A CASE STUDY FROM ZAMBIA

Despite its universal nature, menstruation is cloaked in strong cultural taboos and stigma that often leave adolescent girls1 across the globe uninformed, misguided, and unprepared to navigate their menstrual cycles (Bobel, 2019). The consequences of poor education on menstrual health can contribute to disengagement from social activities, school absenteeism and disengagement from sport and physical activity (Tingle & Vora, 2018; Zipp & Hyde, 2023). These impacts are often more severe in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) of the Global South, where factors such as poverty and poor health care can exacerbate these challenges (Goolden, 2018). With such high stakes, scholars, activists, and policymakers have called for more research on the lived experiences of people who menstruate (Bobel, 2019).

The relatively limited research on the menstrual health and well-being is predominantly focused on menstrual hygiene management (MHM), particularly in LMICs. MHM is about supporting effective, accessible methods to collect or conceal blood during the menstruation period (Sommer & Sahin, 2013). Whilst MHM is important, critical researchers have found that the broader beliefs, attitudes, practices, and knowledge on the menstrual cycle are foundational to understanding girls’ experiences (Bobel, 2019; Zipp, et al. 2019).

The sport for development (SFD) context is particularly challenging for many young people who menstruate, as the fear of leaking through clothing is often exacerbated during physical activity (Women in Sport, 2018). Studies show that menstruation and reaching puberty are barriers to engagement for many SFD participants (Burtscher & Britton, 2022; Marcus & Stavropoulou, 2020; Zipp, et al., 2022). However, research is lacking on the overall impact of menstruation in SFD. A scoping review on menstruation and SFD found only eleven (11) papers on this topic, with most of them focused on MHM specifically (Harrison, 2018).

Developed from grassroots and local organizing to address social, political and economic issues, SFD is now an established movement within international development strategies. Non-governmental organizations (NGO), governments and sport organizations use sport as a platform to address social issues. The SFD movements have deliberately aligned with the United Nation’s (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), a set of 17 goals for international development that range from eliminating poverty, providing universal access to education, gender equality to environmental sustainability, and access to clean water. Common themes in SFD programming include education, health, job/skills training, disability rights, peace-building, and empowering girls and women (Coalter & Taylor, 2010; Mwaanga, 2013; Zipp, et al., 2019).

This study draws on two key themes of research in SFD – gender and health. Research indicates that SFD has the ability to promote positive gender role attitudes, help girls and women build skills (leadership, communication, financial literacy, etc.), develop self-efficacy, support social affiliation and make new networks available to participants that are often unavailable to other girls and women (Hayhurst, et al., 2021; McDonald, 2015; Meier, 2015; Oxford & Spaaij, 2019; Zipp, et al., 2019). SFD research on health is often focused on HIV/AIDS prevention, nutrition and healthy lifestyles, mental health, vaccine promotion and the prevention of various diseases (e.g. malaria) (Hansell, et al., 2021; Schulenkorf & Siefke, 2019). SFD researchers studying gender and health themes in Zambia have called for more focus on lived experiences and local voices (Lindsey, et al., 2017; Mwaanga & Prince, 2016) and more research on menstrual health in SFD (Zipp, et al., 2022).

Of course, SFD has its limitations and risks. Critical scholarship reveals that many of the broad claims of SFD are unsupported by rigorous research or may be overstated (Banda, et al., 2008; Sanders, 2016). Research is often dominated by people from the Global North, which may overlook local voices and lived experiences (Hayhurst, et al., 2021; Lindsey, et al., 2017; Mwaanga, 2010; Nicholls et al., 2011 Zipp & Mwambwa, 2023). Critical feminist researchers have also shown that SFD can reinforce restrictive gender norms and marginalize girls/women and non-binary people (Chawansky & Hayhurst, 2015; Forde & Frisby, 2015; Saavedra, 2009; Oxford & Spaaij, 2019; Zipp & Nauright, 2018). Including girls in SFD programs can be problematic due to social norms, religious beliefs and other restrictions. Namely, SFD is shown to underplay the impact of gender norms and sport (Hayhurst, et al., 2021; Zipp, et al., 2019). We contend that the absence of menstruation in SFD research is a reflection of how girls’ and women’s experiences are overlooked in SFD research.

This project builds from critical feminist research in SFD and research on menstruation in development studies. The purpose of this study is to better understand how adolescent girls in Zambia experience menstruation and menstrual health education in sport for development programming (SFD). Specifically, what are the challenges, attitudes, approaches, support and resources for menstrual health and well-being? We also examine the impact of a physical activity-based menstrual health education program.

Our study took place in the city of Lusaka, the capital of Zambia. Our project partner, the National Organisation of Women in Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation (NOWSPAR), is a lead actor in SFD in Zambia. The authors of this paper are part of the research team, with backgrounds in academic research and teaching, as well as sport for development practice. As a team, we also bring perspectives from Global North and South, with one co-author working at NOWSPAR and living locally in Lusaka.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Menstruation and MHM in the Global South

MHM efforts align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) on good health and well-being (Goal 2), gender equality (Goal 5) and access to clean water and sanitation (Goal 6). The UN program for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) has led the way in MHM advocacy in the Global South (Bobel, 2019). Research and programming in MHM include various interventions, such as supplying (and/or producing) menstrual products (e.g. pads, cups), improving toilet facilities, and education on the menstrual cycle and MHM (Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016). MHM can support psychosocial outcomes for all people who menstruate while helping them to participate in public life, including sport. Nevertheless, the direct relationship between MHM interventions and outcomes like school attendance is unclear. Critics contend that MHM efforts are steeped in restrictive gender norms and serve largely to reproduce neo-liberal hegemonies that govern women’s bodies. MHM teaches girls and women to control and sanitize their menstrual periods so they can continue engaging in public activities and institutions (e.g. school and work) (Bobel, 2019; Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016; Sommer & Sahin, 2013). In SFD more broadly, such “biopedagogies” are ways to incorporate girls and women into sport structures that are designed for boys and men (Hayhurst, et al., 2016).

To better understand the impact of menstruation on peoples’ lives, researchers from across many disciplines have called for more in-depth studies that include girls’ family and social circles (e.g. teachers, church leaders, coaches, health care providers, etc.) (Bobel, et al., 2020). This study is designed to contribute to this area of knowledge and practice on the experiences of people who menstruate.

Menstruation and MHM in Zambia

Zambia is a country in southern Africa, home to nearly 18 million people. A former British colony, Zambia became an independent country in 1964 and is considered a stable democracy. With more than 70 different ethnic groups, the rich and varied traditions of Zambia have endured through colonial rule. English is the official language, yet many ethnic languages are spoken across the country.

According to the UN, Zambia is a “medium” development country, albeit, on the very low end of that category. Zambia ranked 146 out of 189 countries in the 2020 Human Development Index (HDI)2 (United Nations Development Programme). When adjusted for various inequalities, the Zambian HDI drops by over 30%, reflecting the colonial legacies and neo-colonial economic system that exploits indigenous labor for foreign gain (e.g. copper mines owned by UK and Chinese entities) (Human Development Report, 2020). Expected years of schooling is one of the measures that Zambia scores lower in than similar countries, (10.7 years) (Human Development Report, 2020). Researchers and activists in Zambia have argued that one factor for girls leaving school is menstruation and that more in school menstrual health education is needed (Chinyama, et al., 2019; Matunda Lahme & Stern, 2017; Person, et al., 2014).

Traditionally, families bore the responsibility for menstrual health education as elder women handed down knowledge to girls in preparation for marriage (Gondwe, 2017; Jammeh, 2020; Matunda Lahme & Stern, 2017). The rites were celebrated as menarche signaled the entry into adulthood. These rites have been discouraged as now the legal age for marriage was moved to 18, an important protection of human rights for girls. One event in rites of initiation into adulthood such as the Chisungu ritual can be described as a form of women’s education retreat (Mushibwe, 2013; Tamale, 2006). Notwithstanding the roles of these practices in entrenching gender inequality, there are several methodological aspects of these rites that could be useful today. The rites are conducted as an educational community activity, with time and resources allocated to the girls. Methods include role play, demonstration, songs, riddles, illustrations and physical objects crafted for use as teaching aids (Mushibwe, 2013; Richards & La Fontaine, 2013). One study on menstrual health education in Lusaka, explained that:

For the girls’ menstruation is more than pads, pains and stains but a moment to become a woman, to be part of a group, to bond with mothers by receiving teachings, gifts, love and care. The moment to imagine or start romantic relations and to dream about the future. (Jammeh, 2020, p.i)

Researchers at the University of Zambia investigated MHM at five primary and secondary schools in the capital city of Lusaka, reaching 200 schoolgirls, 25 parents, 20 female teachers and 5 head teachers (Sakala & Kusanthan, 2017). They revealed that most schoolgirls (93.6%) felt that menstruation negatively impacted their school engagement. They reported low concentration, distraction, worry and embarrassment over leaking, reluctance to stand in front of the class or participate, and fear of being teased (mostly by boys). Two-thirds of the participants reported missing lessons due to their period. The girls identified lack of private, suitable toilet facilities at school as the most common reason to cut school during menstruation. The study also revealed that the girls lacked basic information on MHM, such as how to use and change pads.

Teachers and students reported that embarrassment, shame and other aspects of stigma were clearly perceived because many girls felt “shy,” “stressed,” or “embarrassed” at school due to their menstrual periods (p. 56). Overall, the study reported that girls felt “long-standing social stigma attached to menstruating bodies, many become isolated from family, friends and their communities, and often missed school or even drop out completely” (p. 62). Misconceptions, stigma and myths surrounding menstruation included that it was “dirty” and “unhealthy,” (p. 62). Sakala & Kusanthan (2017) recommended more MHM education at schools.

Previous studies in Zambia have also focused on MHM over broader menstrual health education and tackling stigma (UNICEF, 2017, UNAIDS, 2016). A 2014 study supported by World Vision International’s (a Christian-based NGO) WASH program examined “perceptions and barriers” to MHM in Zambia (Person, et al., 2014, p. 1). Their study focused on MHM practices specifically, but included aspects of stigma, shame, and menstrual taboo that were discussed in the Sakala & Kusanthan study. In Person’s study, most of the knowledge, beliefs and practices discussed in focus groups and interviews centered on understanding menstruation, restrictive traditions (that prevent girls from participating in cooking, social activities), and keeping menstruation a secret.

The researchers proposed three areas of improvement for schools and communities: increased education and mentoring, providing menstrual product supplies, and improving toilet facilities and adapting practices. While much of the focus is on ‘hardware’ (menstrual products, toilets), the study clearly recommended ‘software’ approaches to breaking down menstrual stigma, such as engaging girls, parents, teachers, and community members in more discussion about menstrual health and MHM.

Menstruation, sport, and SFD

The school-based curriculum in Zambia includes lessons in primary and secondary school on the biological mechanisms of menstruation and recommendations for managing menstrual blood. This is, however, very limited in scope and research shows low quality of the sessions and learning outcomes (Jammeh, 2020). This gap in life-skills education, due to state inefficacy or the disappearance of traditional ritualistic methods, may be substituted by SFD programs which provide menstrual health education, albeit with less comprehensive reach. Therefore, SFD can address a service gap in a form that is acceptable in existing cultural and political contexts, although government programs are generally better suited to provide these services (Banda, 2017; Mwaanga, 2013; Zipp, et al., 2022). SFD programs that use peer leadership and participatory learning approaches may encourage free exploration and questioning about sensitive topics.

NOWSPAR of Zambia is a key provider of SFD for girls and women, offering many programs for all age groups across rural and urban Zambia. One of these programs is called Goal, a multi-sport, educational program for adolescent girls uses sport as the primary learning method for development initiatives across the Global South. The Goal curriculum is designed and coordinated by the Women Win foundation, an international NGO. NOWSPAR facilitates the lessons from the Goal program, with sessions on health, human rights, communication, and financial literacy. The health module includes a lesson on menstrual health and MHM, an often neglected issue. In this way, the Goal program at NOWSPAR helps fill a critical gap in education for Zambian girls. According to a review of the Goal program, learning outcomes on menstrual health are among the most impactful lessons in the program (Marcus & Stavropoulou, 2020).

Overall, however, SFD has largely overlooked the role of menstrual health in participants’ experiences (Zipp & Mwambwa, 2023). Goal is one of the few programs in the SFD movement that includes menstrual health as a key component, along with Moving the Goalposts (MTG) in Kenya and the Naz Foundation’s Young People’s Initiative. New research has highlighted the impact of menstruation, menstrual health and puberty on engagement in SFD with scholars calling for more research and practice on this important topic (Marcus & Stavropoulou, 2020; Harrison, 2018; Zipp & Hyde, 2023; Zipp, et al., 2022).

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

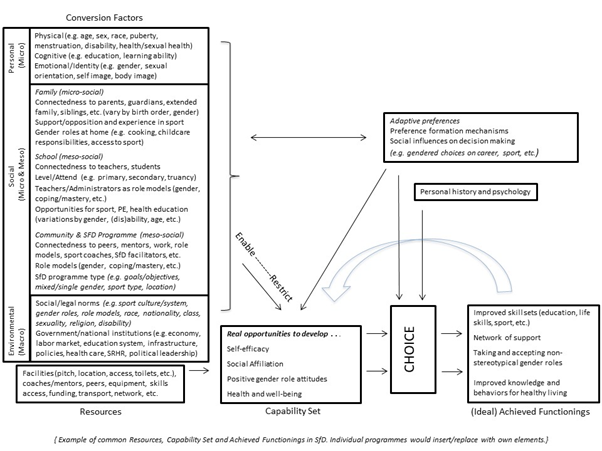

To analyze and understand the participants’ experience, we applied the capabilities approach (CA), which is drawn from Amartya Sen’s ground-breaking research in the field of development studies (Sen, 1999). Sen’s work is applied to SFD via the CA in the SFD model proposed by Zipp et al. (2019) and presented here in Figure 1. The CA shifts the focus of development research from outcomes toward the process of supporting peoples’ freedoms to live the life they desire, free from coercion and restriction (Sen, 1999). These “capabilities” are the crux of the model (Figure 1) amongst resources, conversion factors, and functionings (outcomes). The CA in SFD model is built from diagrammatic models proposed in Ingrid Robeyns’ work, where she examines the real opportunities people are “able to be and do,” (Robeyns, 2017, p. 38). The CA in SFD model also expands upon recent research in SFD that employs the CA (Darnell & Dao, 2017; Suzuki, 2017; Svensson & Levine, 2017).

Figure 1 – HCA Model in SfD (Zipp, et al., 2019)

This model flows from left to right on the bottom level. The resources (left) serve as the starting point, with achieved functionings as an outcome (right) and capabilities as the process (middle), reflecting the goals of individual programs. The upper level of the model (conversion factors, adaptive preferences, and personal history/psychology) serve as factors influencing the process, either restricting or enabling capability development.

This model layers a critical feminist “gender lens” that illuminates some of the key issues for adolescent girls in SFD. Namely, the tiered “conversion factors” (personal, social, and environmental) that intersect and impact participants’ experience of menstruation (Zipp et al., 2019, p. 443). At the personal level, a participant’s own experience is key (age of menarche, experience of symptoms, etc.). On a social (micro and meso) level, family, school and community are key influences. For example, as discussed above, family members have traditionally taught young girls about menstruation in Zambia. These traditions tend to include restrictive norms (e.g. not playing sport while menstruating), but may also be an important source for girls to discuss their experiences, worries and questions. Lessons on puberty, menstruation and sex education at school are also important parts of girls’ experiences. At the environmental (macro) level, the cultural stigma surrounding menstruation is a fundamental problem that causes stress, embarrassment, and shame. Finally, national policies regarding menstruation, such school health curricula and other policies on taxing menstrual products are environmental factors.

These conversion factors all influence (restrict or enable, to varying degrees) a person’s capability development. In this study, the capability set is drawn from the Goal program objectives – the opportunity to understand menstrual health and well-being. If this capability is developed, the participants are empowered to achieve the desired functionings of the program: increased knowledge of the menstrual cycle, methods to cope with symptoms, increased knowledge on MHM, and overcoming stigma to discuss menstrual health.

METHODS

Methodology

With the CA as a theoretical framework, our methodological approach is drawn from research in Development Studies, the home discipline of the CA. Namely, research methods were designed to capture experiences, emotions, ideas, and understandings rather than outcomes of an intervention. In this way, we can better capture how participants can ‘be and do’ rather than evaluate program outcomes. Using mixed methods, we focused on developing a narrative of lived experiences, providing a framework of concepts (delivered as word choice options), while allowing for free exploration and expression (open-ended questions and expressive activities). The research instruments and analysis examined personal and micro/meso social factors such as age, onset of menses, family members and peers they talk about menstruation with etc. We focused on creating meaningful, engaging and rewarding experiences as a responsibility of doing research with children (Huijsmans, et al., 2014). From Punch (2002), we designed data collection instruments (diaries, physical activities) that were understandable for children and had relevance to their lives. Drawing on Zipp (2017), we developed diaries as an effective instrument for capturing the perspectives of adolescent participants in SFD.

Project design

This study was co-created with NGO partner NOWSPAR. NOWSPAR is the leading SFD agency in Zambia working with girls and women. For this study, NOWSPAR leaders and facilitators helped design the data collection tools, a sport-based learning activity, and managed the data collection process. The program was delivered by experienced NOWSPAR facilitators as a part of their weekly programing, meaning the adolescent participants did not experience any sessions outside of their normal program routine. Local NOWPAR facilitators delivered the lessons and distributed the diaries weekly during an after-school Goal program at two primary schools in Lusaka. There were no interventions from the outside research team directly with the adolescent participants.

This project included adolescent participants (n=79) and three (n=3) program facilitators. Each of the adolescent participants completed a diary used during lessons and the facilitators completed a diary that accompanied their lesson guidebook. The diaries included yes/no and fill in the blank questions, answers/items to select amongst a word cloud of choices, open-ended questions/storytelling, and more (see Figure 2), providing both qualitative and quantitative data (120 questions in total). The research design was two-fold; the menstrual health education program (four lessons) and participant/facilitator diaries designed as data collection tools. The lessons were drawn from a variety of education materials, namely the existing NOWSPAR lessons on menstrual health and the www.firstperiod.org website by Dr. Liita Iyaloo Cairney. These materials were embedded into the data collection instruments. The Goal facilitators settled on a basic concept for the spiral-bound, colorful diaries.

Figure 2 – Example diary page

The adolescent participants (n=79) ranged in age from 10 to 17, with a median age of 14 and a mean age of 13.58. Most girls were in grade 8 (n=58) or grade 6 (n=13). Although some of the Grade 8 participants were held back in school due poor academic performance. Six participants were in grade 5 and 1 in grade 3. The wide range of ages and grade levels, as well as the variation of slow and normally progressing pupils created a very diverse participant sample for this study. Participants wrote in their diaries during each of the four (4) lessons over the course of 3 months. Additionally, program facilitators (n=3), all of them adult women from Zambia who worked for NOWSPAR, completed journal entries with each lesson.

For data analysis, the facilitators transcribed responses from diaries into a secure digital file, allowing the diaries themselves to be returned to all participants (with the educational material included). The primary investigator (UK) and co-investigator (Zambia) analyzed all data. We ran descriptive statistics across quantitative data. To analyze the qualitative material, responses were coded into relevant themes and sub-themes based on keywords (e.g. hurt & cramps under the theme for pain) and in relation to the lesson topics (e.g. MHM questions/responses were in the lesson on managing your period). Responses were further coded as positive (e.g. I felt happy to learn new things), negative (e.g. I was scared), neutral (e.g. It was different) and mixed. Coding techniques and thematic analysis techniques were drawn from qualitative data analysis approaches by Braun & Clarke (2006) and reflect common practices in qualitative research in SFD (Zipp, 2017).

KEY FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

From the varied and complex data, three key themes were identified: (1) understanding/learning about the menstrual cycle; (2) pain, discomfort and coping with menstrual symptoms; and (3) stigma, fear and embarrassment surrounding menstruation. Throughout the lessons, the participants indicated a strong desire to learn about the full menstrual cycle, changes in their bodies and what is “normal” menstrual health. In the first lesson, they were given an open-ended question: what is your biggest question about menstruation? Of the 70 responses, most of them, 46 (66%), were focused on understanding various aspects of the menstrual cycle, from practical questions about periods to understanding why they happen.

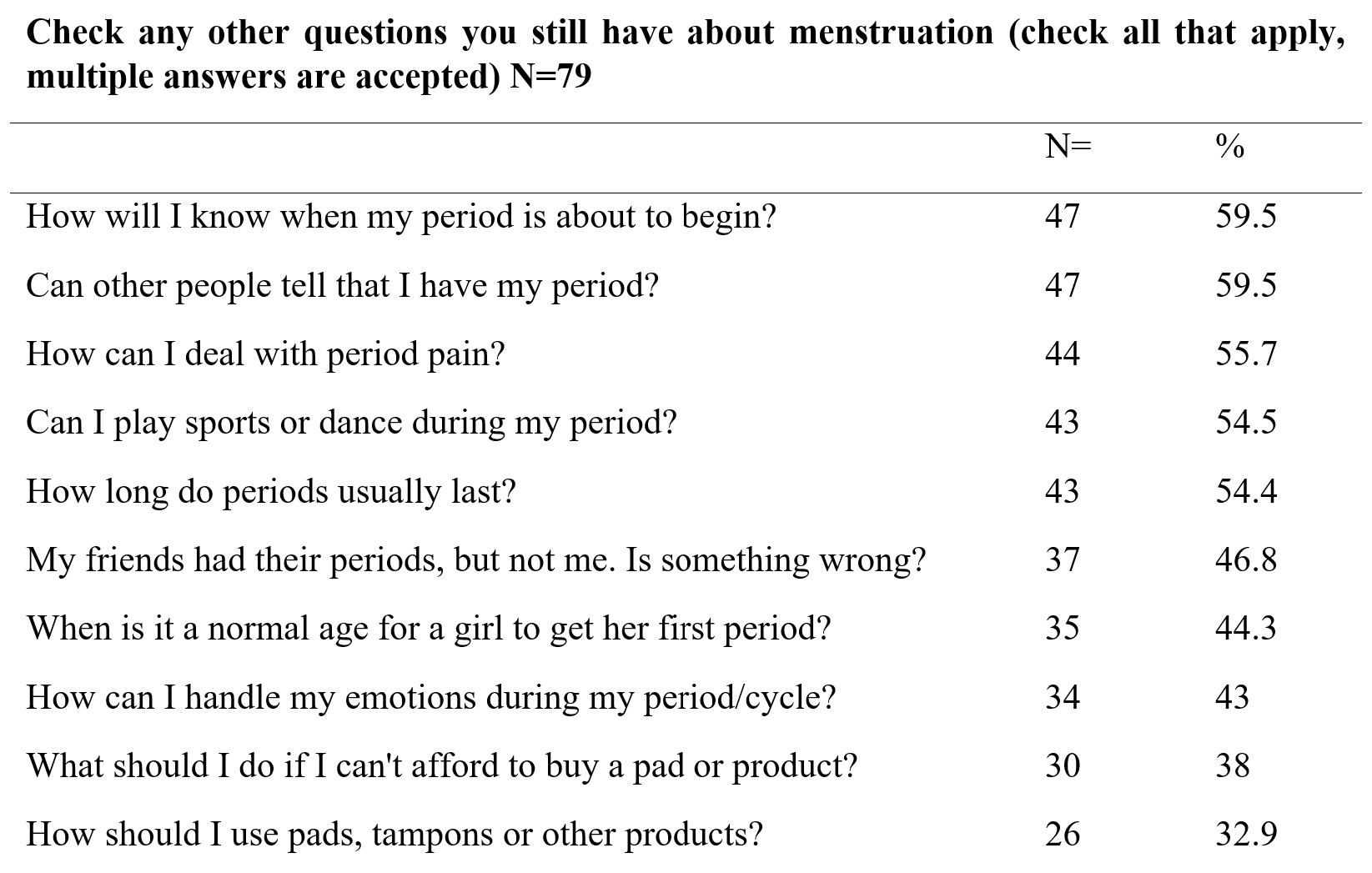

The second most common group of responses was about pain and menstrual symptoms (n=13, 19%) (see next section). Other questions/entries centered on approaches to learning about menstruation (n=4, 6%), talking to others about menstruation (n=3, 4%), managing menstruation (n=2, 3%), and general questions about what to do during menstruation (n=2, 3%). Participants were also asked to select from a menu of questions about menstruation (Table 1). Again, concerns about understanding their cycle, other people knowing about their period, and coping with pain appeared to be prioritized over questions about MHM and menstrual products.

Table 1 – Participant responses to questions about menstruation (as selected from diary options)

1) Understanding and learning about the menstrual cycle

What are periods and why do they happen?

Many participants asked practical questions about the physical experiences of the menstrual cycle. For example, when should periods begin (at what age), how long should menstruation last, can I play sports on my period, is it normal to get two periods per month etc. Many of these questions began with the words “is it normal,” which is how we coded this type of question. Additionally, some participants asked about why periods happen and how it begins. For example, they asked where the blood comes from, why menstruation happens (to girls and not to boys) etc.

Better to learn earlier. One of the most critical findings was that most of the participants did not understand what was happening to them when they experienced menarche (n= 46 of 72, 63.9%). In total, 41 of 79 (51.9%) of the participants did not learn about menstruation until after their twelfth birthday yet believed that girls should learn before the age of 12. This is a key finding as 12 was the median age for menarche, with 44 out of 69 (63.4%) reporting their first period before age 13. The preferred answer to when girls should learn about menstruation was before age 12 (n=65 of 79, 82.3%), with 10 as the median age. Their responses stress the importance of learning about menstruation at an early age in order to avoid the shock, fear, confusion, and embarrassment described in many of the stories about first period experience.

Discussion on understanding and learning about the menstrual cycle. Examining these responses, we gain an understanding of how the conversion factors in the CA in SFD model impact the capability these participants have to understand menstrual health and well-being. Namely, age (personal factor) is key to enabling greater understanding and reducing fear about menstruation. Access to menstrual health education, in this case through an SFD program designed for adolescent girls, is a key social factor.

2) Pain and coping with menstrual symptoms

Concerns about pain

Many participant’s diary responses reflected concerns about coping with common period pain and physical symptoms: “Sometimes when (I) am on my period, I develop menstrual pain and can’t even walk,” (Participant, age 15). Questions about coping with pain were the second most common “biggest question” about the menstrual cycle (n=13 of 70, 18.6%). The topic of pain and pain relief figured widely in their stories (n=11 of 49, 22.4%, Table . The girls wanted to know more about why they felt pain and cramps, how to cope with the pain and in particular if medication was good.

Breathing and stretching for pain reduction. The final lesson of the program was about using stretching and breathing exercises to cope with menstrual pain and focus on “listening to your body.” We consider this an “embodied” approach, one that connects understanding of menstrual health concepts with how our bodies feel, move and are related to our emotional selves. Participants were taught exercises and how to pay attention to the sensations in their body (pain, relief from pan, breathing process, muscles stretching, etc.). The response to this lesson was very positive. Of the 77 responses to “how did the breathing activity and stretches make you feel?” they selected “relaxed” (n=70), “calm” (n=48), and “energized” (n=10) above all other options (stressed (n=0), tired (n=3), embarrassed (n=2), happy (n=2), fun, (n=1), and focused (n=1). On a follow up item, all 70 respondents said they would try the exercises at home. The breathing and stretching activity was also the second most popular choice of lessons that “should be taught in school” (n=58 of 78, 74.4%). However, further questions such as how often the exercises should be done and how effective they were at reducing pain were raised. Some participants felt “embarrassed” doing the exercises (n=2).

The input from all three facilitators (in their diaries) aligns with the participants’ responses. They felt the exercises were the “best part” of Lesson 4 and that it was “important to learn new ways of how to deal with the pain and how it helps through during different phases.” Unfortunately, one of the three groups was unable to do the stretching activities for the lack of a suitable room. One group facilitator reported that a number of girls did not participate in the exercises because they felt “uncomfortable” stretching during their period. It is not clear if they meant physically uncomfortable or if they felt embarrassed. Their refusal to participate is noteworthy and important in understanding their hesitation to do physical activity during menstruation. On the other hand, the fact that they shared their menstrual phase with their facilitator demonstrates an openness to discussing this taboo topic.

Discussion on pain and coping with menstrual symptoms. This topic of pain is important for several reasons, but mainly because it negatively impacts their quality of life. Studies from the United Kingdom (Tingle & Vora, 2018; Women in Sport, 2018) and Global South (Bobel, 2019) indicate that menstrual pain may contribute to bad feelings about menstruation and support harmful myths and restrictions. Specifically, they reveal that menstrual pain can be a distraction making it difficult for people who menstruate to focus or fully engage in and/or enjoy activities such as school, sport, dance, etc.

There is evidence in sport science that exercise can help to reduce cramping, stress, fatigue and improve mood (Bruinvels, et al., 2017). Although it is not possible to directly connect these activities to pain reduction, the positive response to this activity is encouraging. Furthermore, encouraging physical activity throughout menses may dissuade people from quitting sport or skipping physical education lessons during their periods.

In relation to the CA in SFD model, we can see how pain as a personal factor, impacts their lived experience of the menstrual cycle. More specifically, we see that Lesson 4 seemed to enable more understanding of menstrual health and provided practical exercises toward their (ideal) achieved functioning of methods to cope with symptoms. Beyond the practical implications, we note that this lesson focused on how to “listen to your body.” This is an innovative, embodied approach that supports capability development (self-awareness) beyond the specific learning outcomes of the program. For menstrual health-education, this approach might be particularly well-suited for SFD programs, which use physical movement as a key aspect of learning.

3) Stigma, fear, and embarrassment

This theme was the most prevalent across the participant diaries and facilitator feedback. We have organized data from this theme into four sub-themes: Menstruation stigma, fears about leaking, activities and social engagement during periods, talking about menstruation with others.

Menstruation stigma

In our study, the participants discussed aspects of stigma, fear and embarrassment more than any other theme. It is well-documented that the secrecy, stigma and fear of embarrassment about menstruation are problems for people everywhere and lead to negative consequences. The challenges of menstrual stigma in the Global South explored by Bobel (2019) are reflected in the data from this study, with many girls accentuating feelings of embarrassment and fear regarding menstruation. Most girls, 63.7% (n=44 of 69), “felt embarrassed” because of their periods. In one diary session (Lesson 2), participants were asked to “Tell us about the day you got your first period. Write where you were, how you felt, what you did to stay clean, etc.” Their responses (n=63) were varied and complex, reflecting the three main themes. The participants’ stories of menarche were dominated by feelings of fear, worry, and being nervous to talk about it. One passage from a 14-year-old demonstrates this quite clearly:

“Because I was scared that maybe they (family) would shout at me for telling or not telling them, I was so scared to death. How I felt that day was that I was in so much pain that I can’t explain myself on this piece of paper, right now what I can say is that managed to face my fears of not telling them. I just forgot about them shouting at me, went ahead and told my mom and sister that I have started my periods…”

She went on to describe how her family (mother, sister and aunt) had supported her. Her fear was expressed by others, although with less intensity. In many cases (n=30), girls described how someone stepped in to tell them they were menstruating, provide a pad and/or offer comfort and explanation. As discussed above, many participants did not understand menstruation before they had their first period, which seems to contribute to confusion and fear.

Sisters, mothers, grandmothers, teachers, aunts, friends and even strangers were all helpers to these girls. Although, many girls (n=16) expressed a negative emotion such as fear, embarrassment, nervousness, sadness, etc., others were more positive, identifying excited or happy amongst their feelings (n=7). Six (n=6) of the participants had trouble understanding what was happening to them and identifying the blood as menstrual blood. Four (n=4) identified it as a painful experience. Three (n=3) were sent home from school. Three others (n=3) had not yet had their periods. Two (n=2) discovered they were leaking during a sport or physical activity session.

The stories below explain their experience more vividly than numbers: “…I was scared and I kept it to myself to avoid embarrassment,” (Age 15), “I was at school first time I started and I was very scared, I then told my teacher as she told me to go home and clean myself,” (Age 14). Other participants stated:

“The day I got my first period was very happy day and nervous at the same time happy because I felt mature and I become a lady or woman nervous because I didn’t know much about it my friend at school taught me how to stay clean and use a pad,” (Age 14)

“I was on a bus going to school then …one of the women I was with on that bus saw that I made my uniform dirty then she called me back and gave me a pad and a chittenge (cloth pad) and asked me to go back home I was scared because I didn’t know what happened,” (Age 13)

“I started my periods this year I did not know what it was its at school when we were playing at the ground and I was in white my one if my classmate came and told me that I had blood on my shorts, she told me to go and see the teacher I went the teacher gave me something to cover myself with I went home and told mom who later called my Grandmother. Grandmother talked to me on how a girl need to take care of herself,” (Age 12)

“When I started I did not tell anyone about it I stayed for two days without me telling but when I saw the blood was not stopping I told my sister about (it) who then she give a pad and told me that I have become a big girl and that is what big (girls) do,” (Age 14).

“My first period was at home when I saw the blood I felt happy about them coming I went to the bathroom after that I got a pad from my sister and she showed me how to put it,” (Age 16).

In the final lesson, the girls were asked the following: People often think the topic of menstruation is taboo – that it is a secret we shouldn’t talk about. Do you agree or disagree? Why?. We later recognized that the disagree/agree option may have been confusing, and therefore did not analyze which box they ticked. However, their written responses were much clearer and we were able to code and analyze all of them. The majority of participants (n=29 of 45, 64%) clearly indicated that menstruation should not be taboo in their written responses. Of those participants, twenty-two (n=22) wrote that menstruation should be talked about so that people can learn about their bodies, growing up and how to manage their menstrual blood. A 16 year-old participant said “…when we keep it a secret, no one will help you.” Other responses that supported talking about menstruation included:

“All girls and boys should learn about menstruation so that they can understand.” (Age 14), “…the more we talk about it the more we learn about menstruation.” (Age 14), “… we need to share so that others may learn.” (Age 15), and “… we need to teach our friends about what we have learnt.” (Age 15).

By contrast, five (n=5 of 45, 11%) participants wrote that it was a taboo topic and should be kept secret. Their responses included; “Because if you tell others you will even tell wrong people” (Age 14), “…because it is so embarrassing to girls” (Age 13), and “…it is a secret we should not talk about” (Age 14). Clearly, many participants felt that the taboo should be broken because it was preventing people from learning more about menstruation. Some of the responses were neutral (e.g. “I don’t know”).

Fears about leaking

Many of the menarche stories included discussions about leaking. In many cases, someone noticed a stain on their clothing and offered help (e.g. got them a pad, told them to go home from school, etc.). Most girls had had a leak on their clothes (85.7%, n=60 of 70), worried about leaking (90.1%, n=64 of 71) and felt embarrassed to change menstrual products at school (75.7%, n=56 of 74). Many had been teased by boys (49.3%, n=34 of 69) and others had noted that both boys and girls tease others about their periods (more boys than girls).

Throughout the lessons, fear about leaking or being discovered were common stories. Amongst their open-ended stories, eight (8) of the 49 responses were about concerns of leaking or being revealed publicly revealed to be menstruating. One 12 year-old shared a story about her friend being teased and asked how to cope with the situation: “One of my friends her periods started and everyone started making fun of her, how can one deal with such situation?” These stories and their questions reflect the larger problem of stigma and shame surrounding menstruation. Although menstrual health education programs, like the present project, do not address larger social and environmental factors from the CA model that maintain the menstrual taboo, they may be valuable in supporting girls at a personal and micro-social level.

Activities and social engagement during periods

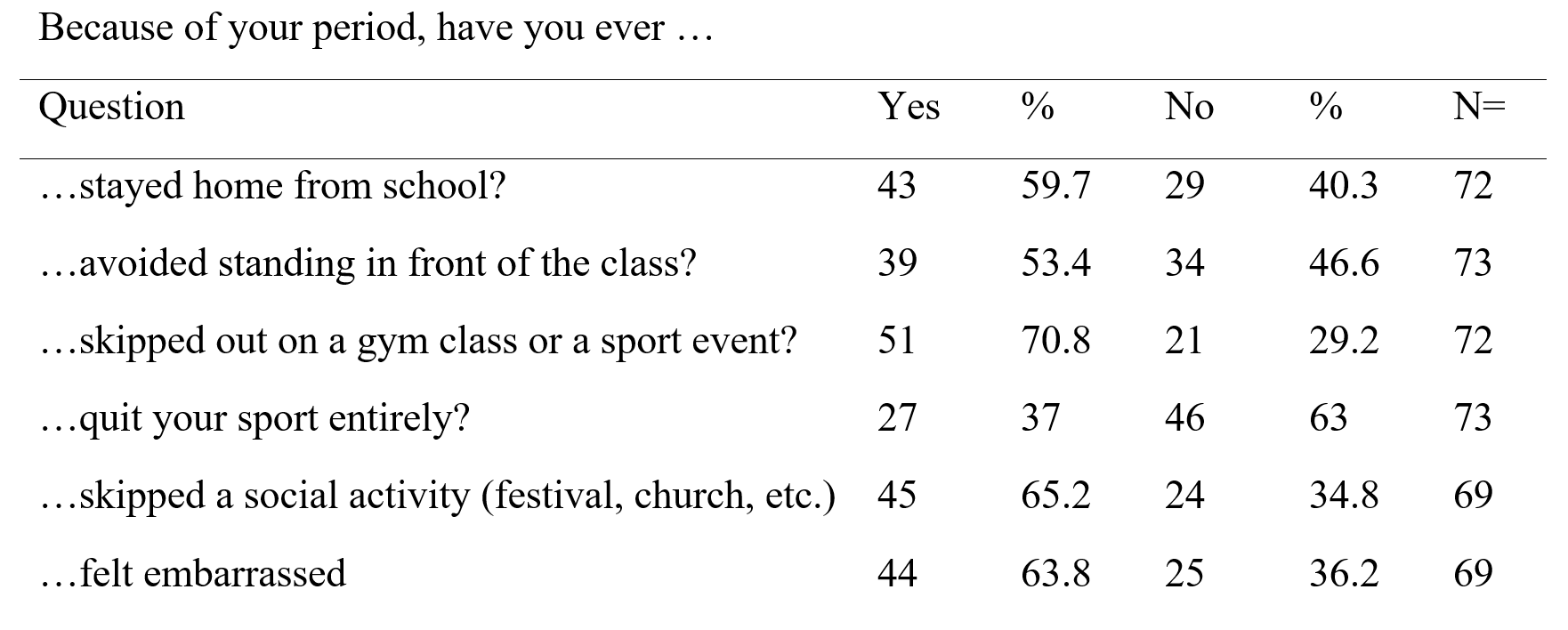

Lessons 2 and 4 included questions about participation and engagement in a variety of school and social activities. In one section (Lesson 2), participants were asked “because of your period, have you ever …” followed by a list of items (Table 2). Most girls (n=43 of 72, 59.7%) reported staying home from school and 39 of 73 (53.4%) avoided standing in front of their classes. They were more likely to skip PE class or sport events than any other activity (n=51 of 72, 70.8%). Twenty seven of 73 quit their sport entirely because of their period (37%). Most girls also skipped other social activities (n=45 of 69, 65.2%) and most had felt embarrassed (n=44 of 69, 63.8%). Clearly, menstrual periods are a significant influence on their decisions to attend and engage in sport, school, and social activities.

Table 2 – Participant responses to diary question about coping with menstruation

A person’s interest and willingness to engage in social activities, school or sport may be influenced by many factors. It is possible pain, discomfort or fatigue were just as or more influential than stigma or fear of leaking. However, this research highlights that their first period stories were about leaking and feeling embarrassed or leaving school/activities to go clean themselves and nearly all the participants worried about leaking at school or in public (n=64 of 71, 90.1%). Other issues relating to girls’ dignity and prevention of embarrassment, such as lack of adequate space with privacy for changing and washing as well as unsuitable clothing may be barriers to participation in sport and PE. It is not uncommon for girls to play sport and physical activity in their uniforms, often skirts or dresses. Therefore, certain activities that involved extensive mobility may be considered risky depending on the menstrual products available.

Talking about menstruation with others

The taboo that surrounds menstruation prevents people from openly discussing this topic. In Lesson 1, participants were asked about who they were talking to about menstruation, which gave better insight as to how they experience menstrual stigma. Most girls relied on older female family members, but many girls also discussed it with friends, making peer education an interesting concept to explore. Program leaders (e.g. Goal facilitators) and teachers were also important sources. In Lesson 4, when questioned if these lessons had prompted them to talk to others about menstruation, 56 of 68 (82.4%) responded that they had spoken to someone “because of these lessons.” In a follow up question, they identified many of the same people (mother (n=11), sister (n=6), grandmother (n=2), etc., but were now much more likely to have talked to a friend (32 of 54, 59.3%). It is possible that they were talking to each other during and after these lessons.

Discussion on stigma, fear and embarrassment

Across each of the sub-themes, shame and embarrassment are woven into the girls’ feelings, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Fears about leaking and reflections on how embarrassed they felt when they had their first period were vividly and frequently expressed in their diaries. These feelings about menstruation appear to be drawn from strong cultural and social norms about gender, modesty, and sexual/reproductive health. Altogether, menstrual stigma functions as an environmental (macro) conversion factor, with menstruation practices (e.g. education, school setting, etc.) functioning at a social (meso, micro) level in the CA model. For example, menstrual stigma restricts the capability development of understanding menstrual health because it hinders the participants’ willingness and opportunity to openly discuss concerns about menstruation.

Limitations and risks

There were several limitations to this research design. It was difficult to conduct this research with rural communities, as was originally planned. Many of those participants do not attend programs or school regularly enough to complete the diaries, so we did not include them in this study. Life in the rural villages is very different from the urban setting in Lusaka and having input from these participants would have brought valuable insight. Future studies should be expanded to the NOWSPAR rural Goal programs for girls who may or may not be enrolled in schools.

Secondly, with participants ranging from age 10 to 17 and enrolled in grades from 3 to 8, there were clearly vast differences in physical, emotional and mental development. Hence, it is difficult to draw nuanced conclusions from the aggregated quantitative data. Furthermore, at least one of the questions was unclear (see above). Younger children or participants with learning disabilities may have struggled to understand all of the material. However, these data are still helpful in identifying themes and, in combination with the richer qualitative data.

Finally, as menstruation is such a taboo topic, it may have been difficult for the participants to share their thoughts and feelings openly in the diaries. Some participants may have felt too embarrassed to share their experiences openly in their diaries.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusions

This study has provided important insight into understanding how girls in Zambia experience menstruation and the impact of a menstrual health education program. The most significant challenges faced by participants are related to menstrual stigma, particularly feelings of embarrassment due to the taboo nature of the topic. Menstrual stigma underlies all of the themes and sub-themes presented and restricts the capability for the participants to understand menstrual health and well-being. Within the CA in SFD framework, this study demonstrates that menstrual stigma is a pervasive and restrictive conversion factor across all levels of evaluation (personal, social, and environmental).

This conclusion is aligned with recent critical research on menstruation in developing countries (Bobel, 2019). The data shows that understanding menstruation through menstrual health education, coping with menstrual symptoms, managing menstrual hygiene, engaging in public life during menstruation, and overcoming the menstrual taboo are all restricted because of the encompassing negativity and stigma of menstruation.

This study highlights the taboo of menstruation within the broader context of SFD and girls. Although menstrual health education is a part of the Goal program curriculum (one lesson), other Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) topics are prioritized in the Be Healthy module. Three lessons are devoted to HIV/AIDS compared to the one on menstruation. While it is agreed that HIV/AIDS is an important topic, it is equally important to learn about the complete menstrual cycle. It is a key foundation for other lessons about sexual and reproductive health and can serve as a rather natural first step in SRHR education. Many SFD curricula focus on sexually transmitted diseases (STD), contraception, and reproductive health. These are all important lessons, but very few include lessons or activities on the menstrual cycle (Harrison, 2018; Zipp, et al., 2022).

SFD may be an effective and important platform to teach menstrual health. As discussed throughout this paper, the listening to your body approach is well-aligned with SFD methods of learning through physical movement. Furthermore, SFD is a relevant context for challenging restrictive norms and myths about menstruation, such as not exercising during menstruation. In demonstrating that movement can be helpful in relieving physical pain and emotional stress, menstrual health lessons in SFD can challenge these broader restrictions. The results in this study show that this SFD menstrual health education program made the girls feel “more empowered” and “more confident” to engage in school, sport and other social activities. More research on this concept will help scholars and practitioners to better understand participants’ experiences and needs.

Recommendations

Menstrual health and adolescent health education should be provided in and out of schools by the age of 10, in order to reach more children before they begin menstruating. Lessons should have a holistic focus on understanding the full menstrual cycle (four phases), approaches to coping with pain and discomfort (e.g. stretching and breathing exercises, medication) and challenging the stigma of menstruation that begets feelings of embarrassment and shame. Leaders in SFD should take a “train the trainers” approach, providing menstrual health education to program facilitators, coaches and teachers. Such programming should be designed by/with local persons, including; educators, health specialists, researchers, social workers, SFD practitioners and other relevant experts in their fields. Menstrual products should be supplied, but with careful steps taken to avoid commercializing education by product brands, a common pitfall in MHM activism (Bobel, 2019). Wherever possible, environmentally friendly products, such as reusable pads and undergarments, should be sought (Zipp et al., 2023).

Research should include adolescent participants of all genders, along with their micro and meso social circles, including family members, teachers, school staff, sport coaches and other community leaders (e.g. religious leaders). Research and programming should also examine relevant policy factors, such as education curriculum, health policies and commercial policies (e.g. taxes on menstrual products). This recommendation aligns with calls across the SFD movement to advocate for broader, macro-environmental change (Darnell & Dao, 2017; Sanders, 2016; Zipp, et al., 2019). Finally, menstrual health education should not be limited to methods for keeping clean and using menstrual hygiene products.

In sum, learning about the complete menstrual cycle is important to the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of adolescents. The girls in this study expressed their desire to learn more about the menstrual cycle and to be taught about it at an earlier age. It is necessary to listen to their voices to support their learning, while engaging families, teachers, community leaders and government officials to reduce the stigma surrounding menstruation.

FUNDING

The University of Stirling funded this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to NOWSPAR and the Women Win Foundation for supporting this project.

NOTES

1 We recognize that gender identity is not binary, but we use binary terms (e.g. girl/boy) in this article to identify people who participate in sport for “girls.” Wherever possible, we use more inclusive terminology (e.g. people who menstruate, all genders).

2 The HDI is a standardized index on health, economic and education outcomes in each country (e.g. life expectancy, standard of living, and access to schools).

REFERENCES

Banda, D. (2017). Sport for development and global public health issues: a case study of National Sports Associations. AIMS Public Health, 4(3), 240. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2017.3.240

Banda, D., Lindsey, I., Jeanes, R., & Kay, T. (2008). Partnerships Involving Sports-for-Development NGOs and the Fight against HIV/AIDS. York: York St John University. https://www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/zambia_partnerships_report___nov_2008.pdf

Bobel, C. (2019). The Managed Body: Developing Girls and Menstrual Health in the Global South. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bobel, C., Winkler, I. T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K. A., Kissling, E. A., & Roberts, T. A. (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org.10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruinvels, G., Burden, R. J., McGregor, A. J., Ackerman, K. E., Dooley, M., Richards, T., & Pedlar, C. (2017). Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research?. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(6), 487-488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096279

Burtscher, M., & Britton, E. (2022). “There Was Some Kind of Energy Coming into My Heart”: Creating Safe Spaces for Sri Lankan Women and Girls to Enjoy the Wellbeing Benefits of the Ocean. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063342

Chawansky, M., & Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2015). Girls, international development and the politics of sport: introduction. Sport in Society, 18(8), 877–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2014.997587

Chinyama, J., Chipungu, J., Rudd, C., Mwale, M., Verstraete, L., Sikamo, C., & Sharma, A. (2019). Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: a descriptive study of knowledge, experiences and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6360-2

Coalter, F., & Taylor, J. (2010). Sport-for-development impact study: A research initiative funded by comic relief and UK sport and managed by international development through sport. Comic Relief, UK Sport Department of Sports Studies, University of Stirling. https://www.idrettsforbundet.no/contentassets/321d9aedf8f64736ae55686d14ab79bf/fredcoaltersseminalmandemanual1.pdf

Darnell, S. C., & Dao, M. (2017). Considering sport for development and peace through the capabilities approach. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 2(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2017.1314772

Forde, S. D., & Frisby, W. (2015). Just be empowered: how girls are represented in a sport for development and peace HIV/AIDS prevention manual. Sport in Society, 18(8), 882–894.https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2014.997579

Gondwe, K. (2017). Zambia women’s ‘day off for periods’ sparks debate. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-38490513

Goolden, E. (2018). Hidden yet shared: An investigation into experiences of the menstrual taboo across higher and lower income contexts [Unpublished Master’s dissertation]. University of Leeds, UK.

Hansell, A. H., Giacobbi Jr, P. R., & Voelker, D. K. (2021). A scoping review of sport-based health promotion interventions with youth in Africa. Health Promotion Practice, 22(1), 31-40. https://doi.org./10.1177/1524839920914916

Hayhurst, L. M., Giles, A. R., & Wright, J. (2016). Biopedagogies and Indigenous knowledge: Examining sport for development and peace for urban Indigenous young women in Canada and Australia. Sport, Education and Society, 21(4), 549-569.

Hayhurst, L. M., Thorpe, H., & Chawansky, M. (2021). Sport, Gender and Development: Intersections, Innovations and Future Trajectories. Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/9781838678630

Harrison, C. (2018). How is menstrual hygiene management incorporated into sport for development programs in the Global South. [Unpublished Master’s dissertation]. University of Stirling. UK.

Hennegan, J., & Montgomery, P. (2016). Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PloS One, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146985

Huijsmans, R., George, S., Gigengack, R., & Evers, S. J. (2014). Theorising age and generation in development: A relational approach. The European Journal of Development Research, 26(2), 163-174. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2013.65

Jammeh, A. (2020). The many meanings of menstruation: practices & imaginaries among school girls in Lusaka, Zambia. IHE Delft Institute for Water Education. https://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/oai:cdm21063.contentdm.oclc.org:masters2%2F107115

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2016, November). Comprehensive sexuality education in Zambia. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2016/november/20161109_zambia

Lindsey, I., Kay, T., Banda, D., & Jeanes, R. (2017). Localizing Global Sport for Development. Manchester: Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526104991

Marcus, R. and Stavropoulou, M. (2020). ‘We can change our destiny’: an evaluation of Standard Chartered’s Goal programme. Standard Chartered. https://odi.org/en/publications/we-can-change-our-destiny-an-evaluation-of-standard-chartereds-goal-programme/

Mutunda Lahme, A., & Stern, R. (2017). Factors that affect menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls: A case study from Mongu District, Zambia. Women’s Reproductive Health, 4(3), 198-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2017.1388718

McDonald, M. G. (2015). Imagining neoliberal feminisms? Thinking critically about the US diplomacy campaign, ‘Empowering Women and Girls Through Sports.’ Sport in Society, 18(8), 909–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2014.997580

Meier, M. (2015). The value of female sporting role models. Sport in Society, 18(8), 968-982. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2014.997581

Mushibwe, C. P. (2013). What are the Effects of Cultural Traditions on the Education of women? The Study of the Tumbuka People of Zambia. Hamburg: Anchor Academic Publishing.

Mwaanga, O. (2010). Sport for addressing HIV/AIDS: Explaining our convictions. LSA Newsletter. 85(1), 61-67. https://www.sportanddev.org/sites/default/files/downloads/mwaanga_lsa_2010.pdf

Mwaanga, O. (2013). Non-governmental organisations in Sport for Development and Peace. In I. Henry and L-M Ko (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport Policy (pp. 109-118). London: Routledge.

Mwaanga, O., & Prince, S. (2016). Negotiating a liberative pedagogy in sport development and peace: understanding consciousness raising through the Go Sisters programme in Zambia. Sport, Education and Society, 21(4), 588-604. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2015.1101374

Nicholls, S., Giles, A. R., & Sethna, C. (2011). Perpetuating the ‘lack of evidence’ discourse in sport for development: Privileged voices, unheard stories and subjugated knowledge. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(3), 249-264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210378273

Oxford, S. and Spaaij, R. (2019). “Gender relations and sport for development in Colombia: A decolonial feminist analysis.” Leisure Sciences 41, no. 1-2,: 54-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1539679

Person, C., Choma Kayula, N. and Opong, E. (2014). Investigating the perceptions and barriers to menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in Zambia. World Vision, International. https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/Final%20MHM%20Report_CPerson_2.14.2014_0.pdf

Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults?. Childhood, 9(3), 321-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568202009003005

Richards, A. and La Fontaine, J. (2013). Chisungu: a girl’s initiation ceremony among the Bemba of Zambia. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315002347

Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-Examined. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0130

Saavedra, M. (2009). Dilemmas and opportunities in gender and sport-in-development. In R. Levermore & A. Beacom (Eds.), Sport and International Development (pp. 124–155). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sakala, B. C. and Kusanthan, T. (2017). Is menstrual hygiene management an issue of school absenteeism: A case of selected schools in Lusaka. International Research Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies. 3(8), 56-72.

Schulenkorf, N., & Siefken, K. (2019). Managing sport-for-development and healthy lifestyles: The sport-for-health model. Sport Management Review, 22(1), 96-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.09.003

Sanders, B. (2016). An own goal in sport for development: Time to change the playing field. Journal of Sport for Development, 4(6), 1–5. https://jsfd.org/2016/04/01/an-own-goal-in-sport-for-development-time-to-change-the-playing-field-commentary/

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sommer, M., & Sahin, M. (2013). Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), 1556-1559. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2013.301374

Suzuki, N. (2017). A capability approach to understanding sport for social inclusion: Agency, structure and organizations. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.905

Svensson, P. G., & Levine, J. (2017). Rethinking sport for development and peace: the Capability Approach. Sport in Society, 20(7), 905–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2016.1269083

Tamale, S. (2006). Eroticism, sensuality and ‘women’s secrets’ among the Baganda. Institute of Development Studies. 37(5). https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/8366/IDSB_37_5_10.1111-j.1759-5436.2006.tb00308.x.pdf;sequence=1

Tingle, C. and Vora, S. (2018). Break the barriers: Girls’ experiences of menstruation in the UK. Plan International UK. https://plan-uk.org/file/plan-uk-break-the-barriers-report-032018pdf/download?token=Fs-HYP3v

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2017, February). Advancing girls’ education through WASH programs in schools. A Formative Study on Menstrual Hygiene Management in Mumbwa and Rufunsa Districts, Zambia. https://www.unicef.org/zambia/media/826/file/Zambia-menstrual-hygiene-management-schools-report.pdf

United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Report. (2020, March). The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene – Zambia. https://zambia.un.org/en/115072-human-development-report-2020-next-frontier-human-development-and-anthropocene

Women in Sport. (2018). Puberty & Sport: An Invisible Stage. The Impact on Girls’ Engagement in Physical Activity. https://www.womeninsport.org/research-and-advice/our-publications/puberty-sport-an-invisible-stage/

Zipp, S. (2017). Changing the game or dropping the ball?: Sport as a human capability development for at risk youth in Barbados and St. Lucia. [ISS PhD Thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam]. http://hdl.handle.net/1765/100422

Zipp, S. & Hyde, M. (2023). Go with the Flow – Menstrual health experiences of athletes and coaches in Scottish Swimming. Sport in Society, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2023.2184355

Zipp, S. & Mwambwa, L. (2023). Menstruation in Motion – Understanding experiences of menstruation in sport in Zambia. In Lotter, S.; Standing, K.; Parker, S. (Eds). Menstruation: experiences from the Global South and North: Towards a Visualised, Inclusive, and Applied Menstruation. London: British Academy.

Zipp, S., & Nauright, J. (2018). Levelling the playing field: Human capability approach and lived realities for sport and gender in the West Indies. Journal of Sport for Development, 6(10), 38–50. https://jsfd.org/2018/04/01/levelling-the-playing-field-human-capability-approach-and-lived-realities-for-sport-and-gender-in-the-west-indies/

Zipp, S., Mwambwa, L. & Goorevich, A. (2023). Sport, development and gender: Expanding the vision of what we can be and do. In Schulenkorf, N., Welty Peachey, J., Spaaij, R. & Collison, H. (Eds.), Handbook of Sport and International Development. Edward Elgar Publishers: Cheltenham.

Zipp, S., Smith, T., & Darnell, S. (2019). Development, gender and sport: Theorizing a feminist practice of the capabilities approach in sport for development. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 440-449. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0126

Zipp, S., Sutherland, S. & de Soysa, L. (2022). Menstrual matters – Innovative approaches to menstrual health and sport for development. In McSweeney, M., Svensson, P. Hayhurst, L., & Safai, P. (Eds), Social innovation, entrepreneurship, and sport for development and peace. Routledge: London.