Eduardo De la Vega-Taboada1, Juliet Pérez-Del Oro1, & Dionne P. Stephens1

1 Department of Psychology, Florida International University, USA

Citation:

De la Vega-Taboada, E., Pérez-Del Oro, J. & Stephens, D.P. (2024). Fútbol Con Corazón: The Cultural Roots and Health Promoting Value of Soccer for Latino Families in the United States. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Sports after-school programs have shown benefits for reducing children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors and improving their socioemotional skills development, positive peer socialization, and prosocial behaviors. Nevertheless, lack of participation remains a challenge for many programs. We conducted nine (9) interviews with parents, residing in a primarily Hispanic-populated city in South Florida, and who had a child enrolled (or were planning to do so) in a soccer-for-development program called Fútbol con Corazón (FCC). We based the qualitative inquiry on the Theory of Planned Behavior to understand motivations and barriers to parental engagement. We conducted a codebook thematic analysis, in which two researchers analyzed the transcripts independently, then discussed discrepancies to reach consensus. Findings revealed that the most relevant factors for improving parental engagement included soccer’s cultural roots, perceived physical and mental health benefits for their children, and proximity to the park. The findings support a growing body of literature indicating that soccer related programs offer culturally sensitive approaches in addition to mental health promoting opportunities for Latino communities in the United States.

INTRODUCTION

After-school programs can reduce children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and improve their socioemotional skills development, positive peer socialization, and prosocial behaviors (Frazier et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2022; Stead & Nevil, 2010). Social and emotional competencies in preschool children (4-6 years old) predict mental health, school adjustment, and success throughout the life course (Adela et al., 2011). Additionally, low-income parents juggling multiple jobs or navigating unemployment may find a complement in after-school programs to improve their children’s socioemotional skills and offer safe and enriching entertainment during out-of-school hours. Thus, when these services are accessible and high-quality, they can help mitigate the potential negative impacts of under-resourced or adverse environments for young children (Adela et al., 2011; Frazier, 2012; Shen et al., 2022).

The growing field of Sport for Development (SFD) programs utilizes the power of sport to improve the socio-emotional and physical skills of children commonly exposed to some levels of adversity. SFD focuses on pursuing systemic changes by addressing social issues such as poverty, health, education, gender equity, and social inclusion. These programs engage underserved participants and their immediate social network with experiences designed to improve their health and well-being. Many occur during out-of-school time, outside of the educational setting, and close to the participants’ homes (LeCrom et al., 2019). However, as noted by Danish and colleagues (2005) there is nothing magical about sports that lead to positive outcomes. Moreover, the process has to be analyzed through a developmental sciences lens by asking what works, under what circumstances (cultures) and for whom (Bronfenbrenner, 1976).

In the United States (U.S.) the lack of participation remains a challenge for many programs, and studies of programs across five of America’s biggest cities found that only 50% to 60% of children in need of out-of-school programs were enrolled in at least one and reported parental satisfaction as an indicator of potential utilization. Studies considered a school-aged child needing after-school programs when their parents could not supervise them during out-of-school hours (Cornelli Sanderson & Richards, 2010; Weitzman et al., 2008). This underutilization is even more relevant for low-SES Latino1 children who are more likely to be physically inactive and whose involvement with organized after-school programs in the U.S. is lower when compared to the general population of children in the U.S. (Day 2006; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012; Lopez et al., 2008). Researchers argue this is due to insufficient financial resources for sports registration and other related costs, restricted access to sports facilities, cultural inappropriateness, and safety concerns (Alliance, 2014; Holt et al., 2011; Simpkins et al., 2017).

Parents and caregivers of preschool children are responsible for enrolling, transporting, and engaging their sons or daughters in out-of-school activities. Therefore, to reduce the disparity in access, it is necessary to understand the motivations and barriers among low-SES Latino parents and caregivers for choosing and sustaining their children’s participation in sports after-school programs. Further, since relevant research has consistently found a positive relationship between programs’ cultural responsiveness, parental engagement, and program efficiency (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Simpkins & Riggs, 2014), we need to expand our understanding of racial/ethnic and other cultural influences. This issue is particularly important when considering Latino populations and a culturally relevant sport such as soccer.

This study aims to identify the parents’ perceptions of a Soccer for Development program for preschool Latino children in South Florida. We will investigate their perceptions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which allow the understanding and prediction of behaviors based on inquiring about attitudes and perceptions. The theory will guide us to identify the present quality of the participants’ parental engagement and the probable level of engagement with the program in the future.

This study aims to explore parents’ views on a Soccer for Development program that focuses on preschool Latino children in South Florida. Employing the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as a framework, we seek to understand and forecast behaviors by examining attitudes and perceptions. This theoretical lens will facilitate the assessment of current parental involvement quality and anticipate future engagement levels with the program.

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

TPB is one of today’s most relevant theories in social psychology for predicting behaviors and was first described in 1985 by Icek Ajzen. TPB states that if an individual sees a behavior positively (attitudes towards the behavior), believes that those around them endorse the behavior (normative belief), and has a sense of control over said behavior (perceived control), they will have a solid intention to behave in that way and be more likely to enact that behavior over time (Ajzen, 1991). Abundant empirical studies have shown TPB’s efficacy in predicting positive behaviors such as physical exercise and sports participation (Conner & Norman, 2022). It has also been used to understand and prevent unhealthy behaviors such as drug use (Cooke et al., 2016; Eaton & Stephens, 2019).

Behavioral beliefs (or attitudes toward the behavior) refer to the perceived consequences of a behavior and one’s attitude toward it resulting from the perceived valence (positive or negative) of those consequences (Ajzen, 2011). For example, suppose a parent perceives that enrolling their child in a program (behavior) will generate discipline and joy for their son/daughter (positive outcome) and outweigh their perception of injury risks (negative outcome). In that case, their attitude towards enrolling their son/daughter in the program will be positive and will increase their likelihood of remaining enrolled over time.

A normative belief (or subjective norms) is the person’s estimation of their social network’s likelihood of supporting or rejecting their intended behavior (Ajzen, 2011). For example, a father who perceives that his relatives, friends, doctors, and priest will support his decision to enroll his daughter in a soccer program is more likely to follow through, than a father who perceives reservations or disapproval from those he trusts. Further, culture and subjective norms are related because culture permeates how people from a particular community or identity group value some behaviors (e.g., for Latino immigrants, playing soccer is a way to connect with their roots).

Control belief (or perceived control) refers to the perceived influence of factors that may facilitate or discourage a behavior; if enabling factors are more potent than limiting ones, there is more likelihood for that behavior to occur over time (Ajzen, 2011). For example, suppose that a parent perceives that transportation to the after-school program is complicated, and no services facilitate the transport. In that case, it is less likely for that parent to enroll their child in the program even if they like the program.

Based on TPB’s applicability on understanding behaviors, this theory will guide the construction of the questioning route to capture the parents’ level of engagement with the program and their likelihood of keeping their son or daughter participating in the program.

Sport for Development (SFD) Builds Socioemotional Skills

Sport for Development (SFD) programs have gained recognition as powerful platforms for promoting socioemotional skills among participants. These programs utilize a unique combination of sports activities and intentional skill-building exercises to foster personal growth, social integration, and emotional well-being. By harnessing the inherent qualities of sports, such as teamwork, discipline, and perseverance, SFD initiatives offer a holistic approach to child and youth development (Coalter, 2013; Shen et al., 2022).

Socioemotional skills encompass a range of competencies that enable individuals to understand and manage their emotions, establish, and maintain positive relationships, make responsible decisions, and effectively navigate social situations. These skills are crucial for personal development, academic success, and future employability. SFD programs provide a uniquely engaging and dynamic environment that challenges youth to push their limits, overcome obstacles, and achieve personal goals, in turn cultivating self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem. As participants witness their progress and achievements in sports, they develop a positive self-image beyond the playing field (Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Holt et al., 2017).

Recently, Positive Youth Development (PYD) approaches have enhanced the understanding of how developmental outcomes, such as social and emotional skills, occur through sports. These approaches are based on developmental sciences, specifically in the Bioecological model coined by Bronfenbrenner (1976) and later developments such as Relational Developmental Systems (Overton & Molenaar, 2015), in which development is contextualized as the co-action of multiple variables such as culture, social interactions, and biology. Thus, socio-emotional learning in children occurs due to intervening not just one but multiple variables simultaneously (e.g., coaches-child interactions, parental training, cultural transformations) (Holt et al., 2016).

Cultural Responsiveness Influences Family Engagement

Incorporating TPB, the research highlights that the disparity in access to and enrollment in organized activities for non-white populations is related to a lack of culturally responsive recruitment methods and activity structures (Yu et al., 2021), which are partly due to the deficiency in understanding about the normative beliefs (subjective norms) of the people that they intend to serve.

The Latino population are the largest growing group in the United States and due in part of minority status Latino youth may face a disproportionate social and contextual challenges to positive development. Moreover, Latino youth often avoid participating in community or after-school programs to avoid forced assimilation (ineffective acculturation), which limits their access to high quality positive youth development programs (Borden et al., 2006; Riggs et al., 2010). Acculturation refers to the process through which an individual undergoes cultural and psychological changes by adjusting to the norms of a particular society, typically occurring during migration. Research indicates that SFD events that consistently include sociocultural aspects to make the participants feel at home contribute to effective acculturation (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014). Thus, culturally responsive practices that understands participants normative beliefs, may help after-school programs to improve minorities participation and development (Riggs et al., 2010).

Moreover, control beliefs, which encompass perceived ease or difficulty in participating in these activities, are evident in the work of Simpkins and Riggs (2014). They suggest that the cultural responsiveness of a program, which can either facilitate or impede participation, is a significant predictor of enrollment, participation, and retention. The feeling of belonging, as informed by self-determination theory, can be seen as a proxy for control beliefs, where the ability to identify with a cultural group within the program plays a role in the perceived control over engagement in the program.

Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, the current study aims to investigate the factors impacting parental engagement through the investigation of a Soccer for Development program (Fútbol con Corazón) conducted in a U.S. region (South Florida), where most of the parents were born in Latin America. We interviewed 9 parents who enrolled their child in a Soccer for Development program or were considering enrollment. We explore into behavioral beliefs (e.g. parent’s perceived impact of the program in their child), normative beliefs regarding cultural norms and expectations of participation, and control beliefs concerning the perceived ease or challenges of engaging with the program. These elements are essential in understanding the motivations behind parental engagement (and desire to enroll their child). The primary research question was: What are the barriers and facilitators for parental engagement with a Soccer for Development program offered in South Florida?

Fútbol con Corazón (FCC) in Alliance with a Community Center in South Florida

FCC promotes Sports for Development programs developed by soccer coaches and psychologists that uses soccer to endorse life skills. FCC has been offered over 14 years in six countries in Latin America, involving more than 100,000 children and adolescents and impacting more than 40 communities. Through nurturing relationships between coaches and participants and based on a structured curriculum, FCC aims to promote four core values (respect, honesty, tolerance, and solidarity) and 14 socioemotional skills such as self-reflection, autonomy, flexible and creative thinking, problem-solving, decision making, self-knowledge and self-esteem, emotion control, stress management, social responsibility and cooperation, empathy, establishing and maintaining relationships, respect and appreciation for others, expression of ideas, emotions and assertiveness. The FCC’s operations in South Florida began in 2020 a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic started. Currently they are conducting eight programs across the region (https://www.fccusa.org/). The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests these skills improve health, peace education, human rights, citizenship education, and other social issues (Puerta et al., 2016). FCC model includes parental engagement and training and co-creating collaborations with allies in their area of influence (https://www.fccusa.org/).

The allied Community Center (CC), whose name will not be disclosed to protect confidentiality, aims to improve the quality of life for children and families. They provide recreational, educational, and cultural activities and comprehensive services in a safe, caring, and nurturing environment. As a private, not-for-profit corporation, this CC seeks “opportunities, partnerships, and resources to meet changing community needs”. They share FCC’s values such as respect, integrity, and sensitivity to diversity.

FCC and CC partner to provide a Sport for Development after-school program offered Tuesdays and Thursdays from 4 pm to 5 pm for the preschool students of the CC (4 and 5 years old). They received support from The Laureus Foundation USA (https://laureususa.com), an NGO that “supports more than 300 programs in over 40 countries and territories that use the power of sports to transform lives”. The NGO was founded in response to Nelson Mandela’s claim that sport has the power to change the world. They have benefited more than 6 million people through their work.

METHOD

Sample

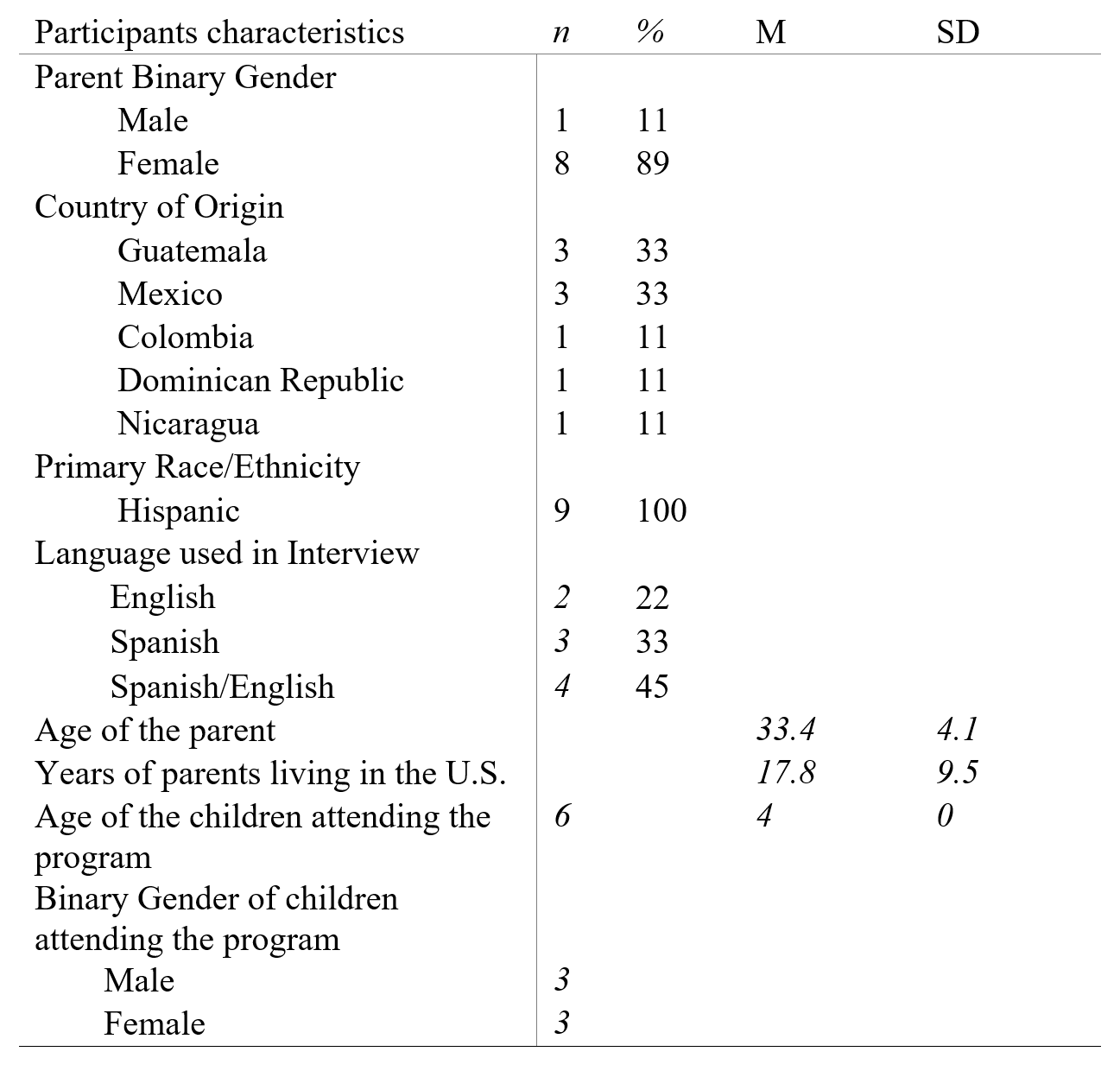

The study was conducted in a city in South Florida affluent with cultural and ethnic diversity and populated mainly by Latinos (65%), some with roots in the Caribbean. The percentage of poverty in the county (21.4%) is almost twice that of the whole country (12.8%), and more than one-third of the population (38.2%) were born outside the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Nine parents (n = 9) consented to participate in the study and despite efforts to recruit fathers, the majority were mothers (8 mothers, 1 father). Seven parents (n = 7, of 19 that originally provided contact information) were recruited during an FCC-Halloween Fair in October 2020. Two more parents (of 3 present on the field) enrolled in the study during an on-site park visit early in 2023 (the third parent was from Jerusalem, and thus ineligible for this study focused on Latino families). All parents resided in the target city at the time of their participation. Parents ranged in age from 23 to 57 years (M = 37, SD = 3). Their homelands included the Dominican Republic (n = 1), Mexico (n = 3), Colombia (n = 1), Nicaragua (n = 1) and Guatemala (n = 3). Six parents had one child enrolled in the program, while three other parents were thinking of enrolling their kids (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Participant demographics

Materials

We based our questioning route on the TPB by dividing the questions into three segments: behavioral belief, normative belief, and control belief. The first segment (behavioral belief) explored parents’/ caregivers’ emotions towards the FCC program, their child’s enthusiasm for or rejection of the program, perceptions of their child’s developmental benefits or losses based on the program, their perception towards the specific sport of soccer, and their attitudes towards the parental workshops. Questions included: How does your child benefit from FCC? How enthusiastic is your child for the program? What motivated you to enroll your child?

The second segment (normative belief) explored perceptions of support/rejection by their social network when enrolling their child or thinking about enrolling their child in a soccer for development program such as FCC. Questions included: What would your family and friends think when you enroll your child in a Soccer for Development program? Who may be against you enrolling your child in a Soccer for Development program? Who may support you? Would it be different if they were boys or girls?

The third segment (control belief) explored perceived barriers and facilitators to enrolling their children in a Soccer for Development program such as FCC. Questions included: What things help your child participate? What things stop or limit your child’s participation? What things stop or limit your involvement in parental workshops? Can you keep your child enrolled and active in FCC for one semester? What about one year? Can you stay engaged in parental activities for one semester? What about one year?

Procedures

FCC expanded its model to Florida a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic. They stopped operations for a few months during the pandemic and then reopened facing a high demand for outdoor children’s activities following quarantine. As they resumed operations, the first author met with the founder and Director of FCC-USA to build a collaboration. After those meetings, the authors sought their university Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to conduct a systematic study of facilitators and barriers to parental engagement. Following approval (IRB-21-0388-AM01), the researchers began recruiting by introducing the study and collecting contact information during a Halloween Fair in 2022 organized by FCC. The researchers called each parent individually to explain the study goals, procedures, risks, and benefits in greater detail. Additional recruitment took place on-site at one park program in early 2023.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author in Spanish (n=3), in a colloquial mix of Spanish and English (n=4) and in English (n=2). The language was decided by parental preference and the interviews were conducted over the phone or Zoom (audio only) with an approximate duration of 30 minutes (M = 28.76, SD = 6). Interviews were audio-recorded, with the participants’ expressed permission.

Data Analysis

The researchers transcribed verbatim the interview recordings and then translated them from Spanish or Spanish/English to English. We utilized the codebook thematic analysis as it aims to determine, analyze, and report patterns that occur in the data and can organize logically following a structure based on an agreed codebook (Braun & Clarke, 2021; Clarke et al., 2015). The researchers coded and analyzed the English transcription documents using MAXQDA, a qualitative data analysis software (VERBI Software, 2021). All participants selected pseudonyms to protect their identities. Authors one and two collaborated on creating a codebook that contained the proposed initial codes (based on interview content) and the guidelines for using them. Then, to ensure trustworthiness, they independently applied the codes (multiple codes were allowed) to quotes from each interview transcript (Clarke et al., 2015). After the initial coding phase, they met to identify overarching themes that would be used to categorize the codes. After this discussion, the researchers compared their initial coding work and revised the interrater agreement to identify each disagreement in the coding. Then, the researchers resolved differences through one-on-one discussions and created a combined version of their coding (Clarke et al., 2015; Jonsen & Jhen, 2009). Next, the researchers reviewed the codes and deleted or combined codes that no longer served their purpose. Also, to ensure credibility the two coders were Spanish and English speakers, had received significant training in qualitative methods and triangulated their coding of the interviews. The first author designed the questioning route.

Author’s Positionality

The first author is a Latino man born in Cartagena, Colombia, who immigrated to the U.S. more than four years ago. He worked for more than 15 years in Colombia, implementing socioemotional programs for the Ministry of Education and leading Positive Youth Development programs through various NGOs that serve children experiencing poverty, violence, and other types of adversities. During this time, he observed how structural inequalities influenced the safety, opportunities, and health disparities experienced by children and adolescents. The first author also witnessed a troubling trend of children and adolescents getting involved in drugs and crime fueled by drug gangs exploiting the region. Despite these challenges, he recognized the power of soccer as both a space and a tool for driving social change. He noted the significant number of soccer activities attracting large groups of boys in the afternoons in Colombia. He became curious about the real impact and the opportunities for improvement of those types of interventions. As a doctoral candidate in developmental psychology, the author aspires to utilize his training, skills, and ample knowledge of academia to better serve children experiencing adversity.

RESULTS

Results are presented under the structure of TPB, through which we analyzed and organized parent responses: behavioral beliefs (attitudes), normative beliefs (subjective norms) and control beliefs (perceived control). For each main theme, we captured the most relevant subthemes, as described below. We then identified the salience of the different subthemes to capture the valence of the main theme.

Behavioral Beliefs (Attitudes)

Experiences with the Staff

The attitude towards the program depends strongly on the parents’ experiences with the staff. In this case, parents described mostly positive experiences with coaches and FCC representatives. These interactions fostered positive associations with the program. When asked about the coaches, some parents stated the importance of the coaches’ patience and that observing that quality in the staff helped them to feel good about the program:

I can see that they have patience with the children even though the children are practically babies and still don’t understand some things […] I have been happy with them. It hasn’t been much time, maybe about two months. But, up until now I feel good about that program.

Children’s experiences with staff were cited as a crucial factor to valuing the program as stated by Lima, a mother who said “Everything depends on that. If the children communicate well with their coach, there are more chances of everything working in harmony in the team.”

This was also supported by a mother (Dominican Power) who described the coaches not only as soccer trainers for their kids but as teammates for their children’s development:

It fascinates me because the coaches always demonstrate… It’s like a second team when the mother is not there. They become responsible for the children, and they can call me if anything happens. If the mother cannot answer the phone, they’ll react accordingly.

Parents also commented about the coaches’ passion for their job and ability to understand their cultural and socioeconomic background. The coaches acknowledged the difficulty the parents face when doing things outside of their culture such as filing forms and were patient supporting the process. The parents valued those behaviors as Hele expressed:

They also enjoy their work […]. When someone doesn’t enjoy their work, it’s bad news and they may not have patience. For us Latinos, sometimes it takes us a bit to get involved in things. This is especially true for me because I am a mom who takes a while to fill out paperwork for my kids. This is especially true in Homestead as well. There are many parents here who the opportunity to study didn’t have, so we must ask a lot of questions and ask for help. Some people don’t have the patience to help. I can see that the coaches are doing their job with love and doing it well.

Meanwhile, when staff did not meet parents’ expectations, parents reported feeling disconnected from FCC, highlighting the importance of consistency when trying to generate positive attitudes towards a program. One mother (Jossie) detailed her frustrations:

Today, for example, our last meeting on Thursday, they could have told us ‘Oh, there’s not going to be soccer next week on Tuesday and Thursday, because of the holidays’, You know? They didn’t tell me, so I had to go to the center, and they told me that there was no soccer today. So, I don’t feel really connected with the coach or whoever’s in charge of the program.

Physical and Mental Health Benefits

All the parents interviewed spoke of the health benefits of exercise in sports programs and/or the therapeutic benefits of using sports as an outlet for stressors in life. This perceived benefit fosters positive emotions among parents, subsequently enhancing their willingness to have their children continue participating in the program. For example, Hele said “Well, I think that when kids are in programs like this, they stay active. As I said, at the same time, it’s healthy for them, physically and mentally.”

Various parents focused on the mental health benefits of Sport for Development programs, even considering the usage of sport as a form of therapy for the Latino population, including not only children but parents too. She stated that: “I have always said that a good sport always takes a child on a good path. […] for us Latinos[…] I think of sports as a therapy for them.” Another mother said that the same is true for the parents: “It’s even good therapy for the parents because when they go to work and leave their children in the sports program, they can know that their children are in good hands”.

Parents perceive the soccer activity as a way to cope with the stress that result from adverse conditions such as immigration, as one mother (Val) said: “I think that it would help because the activity helps them forget about everything stressful in their lives. Children have their own stressors, and it helps them forget and move forward from that.” Thus, the parents value the stress-relieving characteristic of the physical activity.

Some parents placed higher value on the program helping to reduce behaviors that they perceived as unproductive or unhealthy. For instance, Hele viewed sports as a method of redirecting her child(ren)’s attention away from undesirable activities:

I enrolled him in the program because of difficulties with him spending a lot of time on the phone, watching television, and such. That is not healthy for him. However, being in the soccer program and playing is healthier for him.

Emotions, Socialization and Discipline Development

When parents observed improved socialization and discipline in their FCC-enrolled children, their attitudes toward the program became more positive. For example, one mother (Lima) said: “It would be discipline. When you do something consistently, it builds discipline. I would like her to learn that the effort it takes to be disciplined comes with its rewards at some point.” In terms of socialization another mother (Shakira) mentioned that her child is: “learning to build friendships, he is learning to talk more with other kids”.

In terms of socioemotional skills, most of the parents see that the program fosters social skills. Some parents even referred to their desire to enroll their older sons or daughters, so they can develop socioemotional skills:

[Talking about Soccer for Development] It is something that we like very much. It is something that [..]fosters the social skills of the children, but also gives them purpose and makes them more reasonable. I would like my older daughter to achieve it to, since she is a little shy, [I would like her to] socialize more, integrate more. I’d also like her to learn to share because soccer is a sport that involves sharing.

Two mothers mentioned the positive emotions of their children towards the sport, even if sometimes it takes some effort to get them there. Hele stated:

Sometimes, he is enthusiastic about it and says ‘yes, yes, I’ll go’. But sometimes he doesn’t want to go because he wants to be on the phone longer. I don’t let him do that. But when he arrives and sees his friends playing, he enjoys it then.

Val confirmed this idea that her child’s enjoyment of soccer has a positive impact on his emotional state by saying: “First of all, my son is young, and he loves soccer. He loves that activity. As long as he is happy, then I am too.”

Soccer vs Other Sports

Parents with negative attitudes towards other sports often spoke more favorably about soccer. For example, both Dominican Power and Lima viewed American football as an inherently aggressive sport and soccer as the opposite. To this point Dominican Power said: “I don’t think that soccer is aggressive. But I do think that football is very aggressive,” and Lima said: “Soccer is good because it isn’t really fast or rough […] American football, for example. I think it’s aggressive all the time.”

Some parents had a positive attitude towards soccer but felt that it was not a one-size-fits-all activity. For example, Dominican Power said: “Well, sometimes, let’s say, there are children who can’t succeed in sports. Although they may try, they might feel a little sad or depressed by their performance.”

Some parents expressed concern about potential injuries. For example, Hey stated:

Even though I have one that is really active, and she probably will benefit because she’s really active. She loves running, training. She never gets tired. If she falls, she gets up. But it’s just me that… I think they’re fragile and I wouldn’t want them getting hurt all the time and falling or breaking a leg or, you know. I don’t know.

In fact, Hey identified injury as the only explicit risk or disadvantage of sports, saying: “I don’t think there’s a negative thing. Only getting hurt is the negative part of it.” Lima expressed a similar worry, stating: “Well, the only negative for me would be scrapes or bruises that they might get from falling and the possible frustration.”

Normative Beliefs (Subjective Norms)

External Support

Most parents interviewed felt supported by their loved ones and peers in their decision to enroll their child(ren) in soccer. One father (Ronaldo) expressed that his family had high hopes that his son would become a professional soccer player like Cristiano Ronaldo, stating: “They always tell me that my son is going to be a future Ronaldo at 10 years. […] They always support me in everything.” Several other parents felt similarly encouraged by those around them. Val stated: “Yes, as long as my son likes it, I think that they would be on board with it,” Lima stated: “Well, I don’t really have many friends here but the ones that I do have would be cool with it,” and Dominican Power stated: “A while ago, I talked to my family. They have always supported me. […] they have always told me that sports would be good for my son.”

Soccer as a Cultural Root

Several parents saw soccer as a facet of Hispanic/Latino culture. The following dialogue is from a discussion with Ronaldo about how soccer relates to his culture:

Interviewer: Culturally, how connected do you feel to soccer?.

Ronaldo: Yes. I think that everyone identifies with soccer.

Interviewer: Are you referring to Mexico when you say everyone?

Ronaldo: Yes, in Mexico.

Interviewer: And what would be the second sport in Mexico after soccer? Which is the other one that is better known?

Ronaldo: Surely, there isn’t one.

Other parents also reported that soccer was the number one sport in their culture. For example, when asked what sports are most valued in Mexican culture, Val said: “Yes, we really like soccer. After that would be volleyball, and then basketball. But soccer comes first.” Lima responded similarly, stating: “In my country it’s the best. Soccer is the best and practically the only sport. Here in my house, well… my husband likes it very much. The house is filled with happiness when there is a game.” Lima also spoke about the value that soccer programs like FCC bring to low-income individuals and immigrants within the Hispanic/Latino community in Florida:

Florida is a place where a lot of low-income people live. So, this is a very big opportunity because many people from Homestead are immigrants. They are people who work very hard and find it difficult to do things for their children. And the sport that Fútbol Con Corazón offers, soccer, is an excellent opportunity because it’s economical and not expensive. It allows them to place their children in something that’s going to serve them, that they are going to busy themselves with, and that will prevent them from being idle. So, I think that what they’re doing is very beautiful.

Some parents even went so far as to say that soccer is enjoyed across all Hispanic/Latino cultures. For instance, Hele said: “I think Latinos like soccer more,” and Hey said: “Hispanics mostly like soccer, but most Americans like basketball or football. American football.”

The connection with the cultural root that soccer brings to these Latino immigrated parents help them recall positive moments with the sport which may enhance their enthusiasm for enrolling their children, as Ronaldo expressed:

I remember that when I was in elementary school, I started playing soccer. My parents came here, to the United States, and I stayed with my grandparents. My grandparents couldn’t afford cleats, soccer shoes for me. I got my first pair of cleats from my coach, and I remember that they were a little big on me. I even remember the color of the cleats. They were black with yellow stripes. I still remember the game. We lost, but the important thing is that I was happy because I had finally gotten a pair of cleats.

Gender Differences

Most parents, except for a few who recommended alternate sports for girls, said that there was no problem with both girls and boys playing soccer. Those who recommended different sports for girls than boys reported being hesitant about the possibility of their daughter(s) getting hurt. For example, Hey stated: “Girls are more sensitive, they’re more delicate, they’re more fragile.” When asked if her immediate family would support her choice to enroll her daughters in soccer, she added: “Maybe not that much because, the same thing, they’ll think about ‘oh, they might get hurt.’ And the girls are more fragile. Yeah, maybe not as much as the boys.”

Lima echoed the idea that girls who wanted to play sports were not supported as wholeheartedly as their counterparts when asked about how soccer was perceived in society. She said: “Society generally considers that soccer is only for boys.” These Latino parents can distinguish the cultural difference in the U.S. as compared to their home countries, having higher possibilities for enrolling their female children in soccer programs here in the U.S., as Shakira stated: “There [In Guatemala] soccer is more designed for boys, but here, here is the same for everyone, everyone has the same right”.

Control Beliefs (Perceived Control)

Logistical Barriers and Facilitators

These parents have multiple jobs and irregular schedules, common challenges within the low socioeconomic status (SES) Latino population. These factors are obstacles to their attendance at educational events like workshops. While some parents expressed appreciation from those workshops, they also highlighted the barriers that hinder their active participation like work schedules. For example, Hele spoke about her previous experience attending parent workshops:

I personally enjoyed attending. Sometimes I could not go because of my work schedule, but I always went when I had a chance. It is difficult for me to take my son to that program, to his practices, but I try to make time for it because it is very good. It’s important and attending those workshops is very good. It helps us a lot as parents.

When asked if they believed that they could consistently attend parent workshops and take their child(ren) to practice consistently for one full year, all parents said that they could, but some mentioned potential challenges as Dominican Power referred to: “It depends, because sometimes my schedule is different. So that would be something that can cause me not to be able to go”.

Thus, the most recurrent challenges were related to their uncertain and demanding work schedules. The parents acknowledged the program staff’s flexibility and understanding about their demanding schedule conditions and recognized that this flexibility increases their engagement. For example, Val said:

Well, sometimes it’s difficult because of time. I work almost every day. Sometimes I arrive 20 minutes after the other children get dropped off. That happened today. I couldn’t take him because I had to go do something. He had practice today. But, as long as they [the FCC staff] don’t tell me that it’s an issue, I will continue to take him there because he needs it.

On the other hand, some parents found it hard to arrange transportation for their children to attend practice. This issue is also related to demanding schedules. Those same parents mentioned that transportation organized by the soccer program might alleviate this issue. For example, Hele said transportation would help keep her child enrolled over time:

If there was transportation for the children. Of course, I want to be there to see him, and I wouldn’t send him alone all the time, but sometimes my job is all day, and it makes it difficult for me to drop him off and pick him up. It’s what makes it difficult for me. I don’t know if it happens to the other parents.

Val expressed a similar sentiment: “Well, yes. If there was a form of transport to pick up and drop off the children, it would be easier. That way, if someone is busy at work, they don’t have to worry about it.”

However, this solution was not ideal for all; for instance, Hey expressed concerns about those possible transportation arrangements: “Maybe I lack the confidence to let my kids drive with somebody else that is not me.” And some of them did not see the need for transportation because the park where the program takes place is close to their homes, as Ronaldo expressed: “It’s easy because it’s close to us”. In general, the parents perceived that the FCC structure, which is free of charge, close to their home and has a time-appropriate and a flexible schedule helps them keep engage with the program, as Lima expressed: “Fútbol Con Corazón makes everything simple for everyone. If we’re talking about in general, there are many obstacles. Some examples would be money, schedule, and distance.”

DISCUSSION

To understand family engagement in after-school programs, we applied the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) framework to the Fútbol Con Corazón (FCC) initiative in a predominantly Latino-populated region in South Florida. The results showed strong parental engagement based on responses to three sets of questions, corresponding to specific TPB factors: behavioral beliefs (attitudes), normative beliefs (subjective norms), and control beliefs (perceived control).

First, the questions on behavioral beliefs revealed predominantly positive attitudes toward and experiences with the program, based on parent interactions with staff and perceived enthusiasm from their child(ren). The positive contact with staff and the physical, mental health, and physical health benefits they expected for their child(ren) outweighed reported concerns (mainly potential for injury associated with playing sports).

Second, the questions on normative beliefs confirmed the importance of soccer for the Latino culture and the value placed by parents (and others in their social networks) on organized after-school care. Universally, parents reported enthusiasm within their social networks for children participating in programs like FCC, that merge soccer and socio-emotional skills.

Third, the questions on control beliefs showed high accessibility to the program, with few barriers identified related to transportation or cost. The program’s place in a park close to families’ homes was a positive feature. Nevertheless, uncertainty associated with tight (and sometimes unpredictable or inconsistent) job schedules and competing demands (most parents had multiple jobs to sustain their families) were mentioned as concerns that may interfere with sustained engagement with the program over time. Despite this, the number of facilitators, compared to the number of barriers to parental and child engagement, were favorable towards enthusiasm for and engagement with the program.

The results prominently reflect the interrelatedness of the three categories of beliefs. Notably, parents’ attitudes towards the program (behavioral beliefs) were influenced by the cultural background of the staff (normative beliefs), which in turn appeared to bolster the parents’ perceived ability (control beliefs) to maintain engagement with the program over time. Furthermore, the findings’ prominence of behavioral and normative beliefs suggests that an emotional connection and cultural resonance with the program may overshadow logistical concerns in influencing continued participation.

Interestingly, the apparent endorsement of soccer involvement for both boys and girls by others seems to challenge the conventional Latino societal belief that girls and women should not play soccer (Knijnik & Garton, 2022). While we anticipated and discovered a strong affinity of the Latino population with soccer, considering it as a paramount sport in Latin America intricately woven into its cultural fabric (Cuesta & Bohorquez, 2012), we were also prepared for, yet did not find, the gender disparities and exclusions commonly observed in Latin American soccer programs (Bland-Lasso, 2018). This discrepancy might arise from the acculturation processes that the Latino families experience upon their arrival in the US (Glass & Owen, 2010). SFD, particularly soccer can be seen as an appropriate tool for accompanying acculturation processes for Latino population living in the U.S., which has been supported by other research in the U.S. where sport events have been used as ‘vehicles’ for social integration by including certain conditions (Jones et al., 2021) like the ones observed in the FCC programs.

The results highlight soccer’s promising perception and potential to enhance socio-emotional learning during early childhood. Parents noted the program’s positive impact on their children’s emotions and well-being, even considering it therapeutic. They appreciated their children’s improved ability to engage safely with peers outdoors. These experiences are especially meaningful in the early stages of growth, potentially fostering positive developmental pathways that can mitigate the adverse effects of poverty in low-income households, where SFD can prevent violence exposure and improve developmental pathways (Adela et al., 2011; Blair & Raver, 2012; De la Vega-Taboada et al., 2023).

Finally, the deeply ingrained nature of soccer within the Latino culture deserves mention. It should be harnessed to enhance parental engagement and children’s participation in after-school programs among immigrant Latino communities in the US. This approach can address the prevailing issue of low participation rates in after-school programs within this demographic (Borden et al., 2006).

As a limitation, qualitative methods use small sample sizes that may not represent the diverse experiences of families from different regions (Palinkas et al., 2015). In this case, the participant’s recruitment was challenging due to concerns (Martinez et al., 2012).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper examined the engagement of parents and their children in the Fútbol Con Corazón (FCC) after-school program using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) framework. The study explored the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived control factors that influence parental involvement in this soccer-based initiative within a predominantly Latino community in South Florida. The results underscore parents’ positive attitudes toward the program, driven by their favorable experiences with staff, the perceived physical and mental health benefits of participation, and their children’s positive emotions and socialization derived from the program. Moreover, parents demonstrated strong normative beliefs, considering soccer an integral facet of their culture, and finding support from their social networks for enrolling their children in the program. Perceived control was generally high, with the proximity of the program’s location, transportation accessibility, and economic affordability being identified as facilitators. However, challenges related to inconsistent work schedules and competing demands were potential barriers to sustained engagement.

The study also shed light on the evolving gender dynamics within Latino families, as many parents supported and encouraged both boys and girls to participate in soccer programs, challenging traditional gender stereotypes associated with the sport. Additionally, implementing FCC in a new cultural context highlights the potential for Sport for Development organizations to disseminate their design and expand their impact and methodologies across different regions.

The findings have implications for organizations working with Latino populations, suggesting that leveraging soccer’s cultural significance and emphasizing the support of social networks can enhance parental engagement in after-school programs. However, it is essential to recognize the limitations of this study, which focused on a specific program within a specific region. Future research should explore similar programs in diverse settings to validate these findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of how soccer can be harnessed to foster socio-emotional development and parental engagement among various populations.

NOTES

1 The authors recognize that there is disagreement in how the term Hispanic, Latino and LatinX is applied and used to identify Spanish speakers in the United States. The authors have chosen to use the term Latino in the present study because the research participants self-identified with this term (Fry & Lopez, 2012; Guidotti-Hernández, 2017). Further, this term better captures the nation of origin, immigration identities, and cultural linguistic norms of this unique group of Hispanic parents (Bedolla, 2003).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

The Psychology Graduate Student Seed Fund Award (GSDFA) provided by Florida International University supported this project.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the openness of the Organization FCC and the support they provided during the design and the recruitment process.

REFERENCES

Adela, M., Mihaela, S., Elena-Adriana, T., & Mónica, F. (2011). Evaluation of a program for developing socio-emotional competencies in preschool children. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2161-2164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.419

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

Ajzen, I. (2011). Behavioral interventions: Design and evaluation guided by the theory of planned behavior. In M. M. Mark, S. I. Donaldson, & B. C. Campbell (Eds.), Social Psychology and Evaluation (pp. 74-100). New York.

Alliance, A. (2014). Taking a deeper dive into afterschool: Positive outcomes and promising practices. ERIC Clearinghouse. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED557914.pdf

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2012). Child development in the context of adversity: experiential canalization of brain and behavior. American Psychologist, 67(4), 309. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027493

Bedolla, L. G. (2003). The identity paradox: Latino language, politics and selective dissociation. Latino Studies, 1(2), 264-283.

Bland-Lasso, L. (2018). Challenging Social Exclusion Through Sport: A Case Study of Marginalized, Adolescent Girls in Bogotá, Colombia [Doctoral dissertation, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa].

Borden, L. M., Perkins, D. F., Villarruel, F. A., Carleton-Hug, A., Stone, M. R., & Keith, J. G. (2006). Challenges and opportunities to Latino youth development: Increasing meaningful participation in youth development programs. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28(2), 187-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986306286711

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

Coalter, F. (2013). ‘There are loads of relationships here’: Developing a programme theory for sport-for-change programmes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(5), 594-612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212446143

Cooke, R., Dahdah, M., Norman, P., & French, D. P. (2016). How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 10(2), 148-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.947547

Cornelli Sanderson, R., & Richards, M. H. (2010). The after-school needs and resources of a low-income urban community: Surveying youth and parents for community change. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 430-440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9309-x

Conner, M., & Norman, P. (2022). Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 923464.

Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J.A. Smith (Ed) Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods (pp. 222-248).

Cuesta, J., & Bohórquez, C. (2012). Soccer and national culture: estimating the impact of violence on 22 lads after a ball. Applied Economics, 44(2), 147-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2010.500275

Danish, S. J., Forneris, T., & Wallace, I. (2013). Sport-based life skills programming in the schools. In School Sport Psychology (pp. 41-62). Routledge.

Day, K. (2006). Active living and social justice: planning for physical activity in low-income, black, and Latino communities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72(1), 88-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360608976726

De la Vega-Taboada, E., Rodriguez, A. L., Barton, A., Stephens, D. P., Cano, M., Eaton, A., … & Cortecero, A. (2023). Colombian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Violence and Opportunities for Safe Spaces Across Community Settings. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584231164643

Eaton, A. A., & Stephens, D. P. (2019). Using the theory of planned behavior to examine beliefs about verbal sexual coercion among urban black adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(10), 2056-2086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516659653

Frazier, S. L., Chacko, A., Van Gessel, C., O’Boyle, C., & Pelham, W. E. (2012). The summer treatment program meets the south side of Chicago: Bridging science and service in urban after‐school programs. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(2), 86-92. https://doi.org10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00614.x

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698-713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.698

Fredricks, J. A., & Simpkins, S. D. (2012). Promoting positive youth development through organized after‐school activities: Taking a closer look at participation of ethnic minority youth. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 280-287. https://doi.org.10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00206.x

Fry, R., & Lopez, M. H. (2012, August 20). Hispanic student enrollments reach new highs in 2011. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2012/08/20/hispanic-student-enrollments-reach-new-highs-in-2011/#:~:text=For%20the%20first%20time%2C%20the,share%20of%20all%20college%20enrollments.&text=Hispanics%20are%20the%20largest%20minority,year%20(Fry%2C%202011)

Guidotti-Hernández, N. M. (2017). Affective communities and millennial desires: Latinx, or why my computer won’t recognize Latina/o. Cultural Dynamics, 29(3), 141-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374017727853

Glass, J., & Owen, J. (2010). Latino fathers: The relationship among machismo, acculturation, ethnic identity, and paternal involvement. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(4), 251-261. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021477

Holt, N. L. (Ed.). (2016). Positive Youth Development Through Sport. Routledge.

Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., MacDonald, D., Strachan, L & Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(1), 1-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704

Holt, N. L., Kingsley, B. C., Tink, L. N., & Scherer, J. (2011). Benefits and challenges associated with sport participation by children and parents from low-income families. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12(5), 490-499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.05.007

Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2010.488049

Jones, G. J., Taylor, E., Wegner, C., Lopez, C., Kennedy, H., & Pizzo, A. (2021). Cultivating “safe spaces” through a community sport-for-development (SFD) event: Implications for acculturation. Sport Management Review, 24(2), 226-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1879559

Jonsen, K., & Jehn, K. A. (2009). Using triangulation to validate themes in qualitative studies. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: an International Journal, 4(2), 123-150.

Knijnik, J., & Garton, G. (Eds.). (2022). Women’s Football in Latin America: Social Challenges and Historical Perspectives Vol 2. Hispanic Countries. Springer Nature.

LeCrom, C. W., Martin, T., Dwyer, B., & Greenhalgh, G. (2019). The role of management in achieving health outcomes in SFD programmes: A stakeholder perspective. Sport Management Review, 22(1), 53-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.09.005

Lopez, C., Bergren, M. D., & Painter, S. G. (2008). Latino disparities in child mental health services. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(3), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2008.00146.x

Martinez, C. R., McClure, H. H., Eddy, J. M., Ruth, B., & Hyers, M. J. (2012). Recruitment and retention of Latino immigrant families in prevention research. Prevention Science, 13, 15-26.

Overton, W. F., & Molenaar, P. C. (2015). Concepts, theory, and method in developmental science: A view of the issues. In W.F. Overton & P.C.M Molenaar (Eds), Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, (pp. 1-8). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy101

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Puerta, M. L. S., Valerio, A., & Bernal, M. G. (2016). Definitions: What Are Socio-Emotional Skills?. World Bank Library. Retrieved from: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-0872-2_ch3

Riggs, N. R., Bohnert, A. M., Guzman, M. D., & Davidson, D. (2010). Examining the potential of community-based after-school programs for Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 417-429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9313-1

Shen, Y., Rose, S., & Dyson, B. (2022). Social and emotional learning for underserved children through a sports-based youth development program grounded in teaching personal and social responsibility. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 1, 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2022.2039614

Simpkins, S. D., & Riggs, N. R. (2014). Cultural competence in afterschool programs. New Directions for Youth Development, 2014(144), 105-117. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20116

Simpkins, S. D., Riggs, N. R., Ngo, B., Vest Ettekal, A., & Okamoto, D. (2017). Designing culturally responsive organized after-school activities. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(1), 11-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558416666169

Stead, R., & Nevill, M. (2010). The impact of physical education and sport on education outcomes: a review of literature. UK: Institute of Youth Sport School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University. https://www.icsspe.org/es/system/files/Stead%20and%20Neville%20-%20The%20Impact%20of%20Physical%20Education%20and%20Sport%20on%20Education%20Outcomes.pdf

Spaaij, R., & Schulenkorf, N. (2014). Cultivating safe space: Lessons for sport-for-development projects and events. Journal of Sport Management, 28(6), 633-645. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0304

U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). QuickFacts Homestead City, Florida. Retrieved January 12, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/homesteadcityflorida/PST045221

Verbi Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2020 [computer software]. MAXQDA 2023 [computer software].

Weitzman, B. C., Mijanovich, T., Silver, D., & Brazill, C. (2008). If you build it, will they come? Estimating unmet demand for after-school programs in America’s distressed cities. Youth & Society, 40(1), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X08314262

Yu, M. V., Liu, Y., Soto‐Lara, S., Puente, K., Carranza, P., Pantano, A., & Simpkins, S. D. (2021). Culturally responsive practices: Insights from a high‐quality math afterschool program serving underprivileged Latinx Youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(3-4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12518