Julia Ferreira Gomes1, L.M.C. Hayhurst1, M. McSweeney2, T. Sinclair3, and F. Darroch4

1 Department of Kinesiology and Health Science, York University, Toronto, Canada

2 School of Kinesiology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA

3 Department of Social Science, York University, Toronto, Canada

4 Department of Health Sciences, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada

Citation:

Gomes, J.F., Hayhurst, L.M.C., McSweeney, M., Sinclair, T., & Darroch, F. (2023). Trauma- and violence-informed physical activity and sport for development for victims and survivors of gender-based violence: A scoping study. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Recent literature has highlighted the need for trauma-informed programming and research in sport. Specifically, studies have noted the importance of developing trauma-informed approaches to sport for development (SFD) initiatives that work with victims and survivors of gender-based violence (GBV). The purpose of this scoping review was to: (1) examine the synergies between trauma-and violence informed physical activity (TVIPA) programs and sport for development (SFD) programs globally for survivors/victims of GBV; and 2) assess the implementation of TVIPA in future SFD programming for survivors and victims of GBV. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework, we systematically reviewed three electronic databases: ProQuest, EBSCO, and Web of Science. Following thematic analysis of the selected articles revealed that TVIPA should be further explored in SFD programming as a possible approach for victims and survivors of GBV. Taken together, we suggest the need for trauma-and violence-informed SFD, especially: 1) for vulnerable SFD program participants; and 2) to better understand and prevent GBV experiences in SFD and sport more broadly. This is one of the first studies to explore the synergies between TVIPA and SFD, contributing to novel trauma research in the context of sport, development and physical activity.

TRAUMA- AND VIOLENCE-INFORMED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SPORT FOR DEVELOPMENT FOR VICTIMS AND SURVIVORS OF GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE: A SCOPING STUDY

In recent years, organizations in the sport for development (SFD) sector that work with populations who have experienced violence have increasingly recognized the need for trauma-informed approaches to sport (e.g., Doc Wayne, Swiss Academy for Development). The SFD sector is comprised of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), corporations, communities, international organizations (e.g., United Nations), and individuals who adopt sport to intentionally achieve development priorities often associated with the Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., gender equality, conflict resolution) (Kidd, 2008; 2011). Organizations use SFD as a tool to help support marginalized and impoverished communities (Whitley et al., 2013). Notably, numerous SFD organizations seek to work with populations who may have experienced violence and trauma, particularly women, including cis, transgender and nonbinary people, and members from the 2SLGBTQIA+ community (e.g., AKWOS, Kolkata Sanved, Women Win). Relatedly, there has been growing empirical research into sport, gender, and development (SGD), a substream of SFD focused on the gendered dynamics, relations, and (in)equalities within SFD programs (Chawansky, 2011; Collison et al., 2017; Hayhurst et al., 2021; Oxford & McLachlan, 2018; Zipp, 2017). Indeed, SFD programs have aimed to challenge gender and health inequities by improving gender relations and reducing gender-based violence (GBV).

GBV is defined as violence against people based on their gender expression, gender identity or perceived gender (Cotter & Savage, 2019; Government of Canada, 2022). Some common forms of GBV include intimate partner violence, violence against women, sexual violence, sexual harassment, and domestic violence. Emerging data about lockdowns and COVID-19 stay-at-home orders have revealed that violence against women and girls, including both domestic violence and sexual abuse, has increased in several countries, such as France, Argentina, Singapore, Canada, the UK, and the USA (Sri et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has thus resulted in a ‘shadow pandemic’ or ‘a pandemic within a pandemic’, whereby GBV has intensified and been exacerbated. At the same time, Hall et al. (2021) have suggested that there is now a pandemic of physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles that “will persist long after we recover from the COVID-19 pandemic” (Hall et al., 2021, p. 108). With the onset of COVID-19 ‘shadow pandemics’ and physical inactivity trends, the need to create and manage safe and equitable sport and physical activity interventions for people who have experienced GBV is thus a pressing issue.

Researchers have recently investigated the use of trauma- and violence-informed physical activity (TVIPA) to support individuals who have experienced GBV (Darroch, et al., 2022a; van Ingen, 2021). TVIPA is an approach to physical activity programming, adapted from a trauma- and violence-informed care (TVIC) perspective in health care (Darroch et al., 2018; Darroch et al., 2022a). TVIC accounts for the intersecting impacts of: (a) broader structural and social conditions, (b) ongoing violence, and (c) institutional violence (Wathen et al., 2021). TVIPA utilizes a TVIC approach to prevent re-traumatization of participants and staff involved in physical activity programs (Darroch, et al., 2022a). Despite the growing research on the use of TVIPA and the prevalence of GBV around the world, there have been no comprehensive studies examining the ways in which TVIPA is utilized by, or taken up within, SFD programs serving people who have experienced GBV.

In light of these gaps, our two research questions guiding our scoping review included: 1) What are the synergies between SFD and TVIPA programs serving victims/survivors of GBV; and 2) How has TVIPA been used within, or to inform, SFD programs for people who have experienced GBV? We conducted a scoping review of existing literature on SFD and TVIPA, focusing on programs that serve survivors and victims of GBV. The purpose of this scoping review was thus to summarize the research that has taken place within this area and offer future directions for research, policy, and practice. Given that many SFD programs and organizations aim to respond to social issues and – as will be evident from this review – work with populations that have experienced GBV, several recommendations from this review are applicable to SFD management and practice. We hope that these recommendations will be useful in stimulating discussions among stakeholders of SFD, regarding how TVIPA can inform programming for victims/survivors of GBV.

In the next section, we provide an overview of our methods for the scoping review. Following this, we describe the results of our scoping review, including common themes identified across the 21 articles examined in relation to TVIPA and SFD for survivors of GBV. In conclusion, we discuss key recommendations based on the scoping review that are relevant for policy-makers, researchers, and practitioners, and suggest future directions for empirical analysis.

METHODS

While there is no universal or clear-cut definition of scoping reviews, they are generally understood to map out key concepts and research in an area that has not been comprehensively reviewed before (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Scoping reviews are defined generally to, “map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available” (Mays et al., 2001, p. 194, emphasis in original). As Arksey and O’Malley suggest, a key difference between a systematic and scoping review is that the latter focuses on examining a wide variety of studies without an analysis of the quality of studies (as in a systematic review) to better respond to guiding research questions and provide insights into a specific area of study. Regardless of the differences between scoping and systematic reviews, both studies must be conducted in a rigorous and transparent way (Mays et al., 2001). For this study, we followed the recommendations outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for scoping reviews, which we detail in the following sections.

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

In this study we used two research questions to guide our review of the literature:

- What are the synergies between SFD and TVIPA programs serving victims/survivors of GBV?

- How has TVIPA been used within, or to inform, SFD programs for people who have experienced GBV?

It is important to highlight which terms or components of a research question are significant for a scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). For these questions, we define GBV, SFD, and TVIPA as outlined in the Introduction section. While there is no universal term for GBV, SFD, or TVIPA, we adopted these terms to determine the extent of the literature included in this review. At the same time, the definitions we utilized are broad in nature – thus allowing us to begin our review with a wide lens and limit the possibility of overlooking potential articles for the review.

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

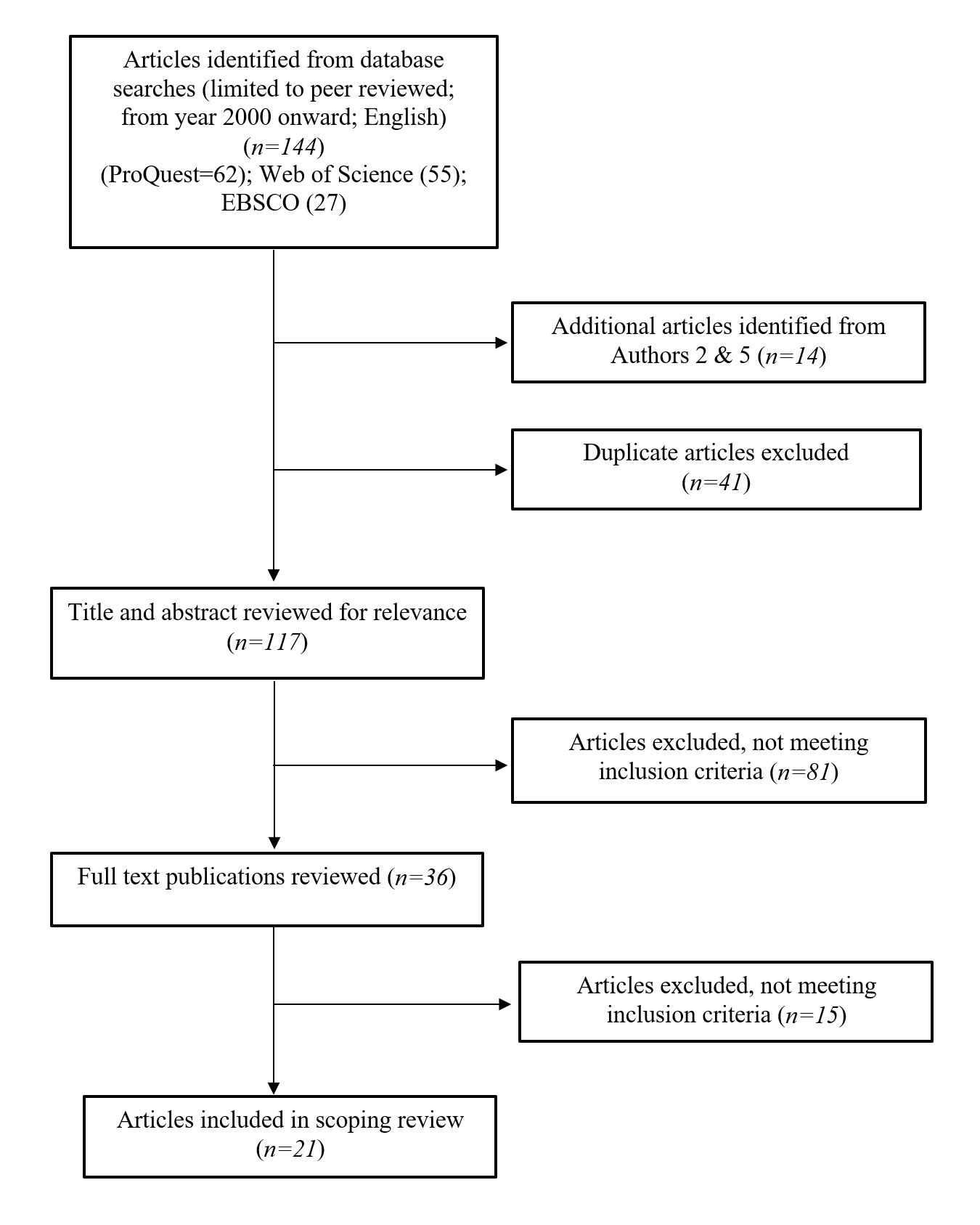

Identifying relevant studies progressed in two phases. Following a consultation with a research librarian, the authors conducted a search across three databases including Web of Science, ProQuest, and EBSCO in August 2022. Using the search terms (trauma* OR “trauma- and violence-informed” OR “trauma-informed” OR “trauma-sensitive”) AND (“sport development” OR “sport for development” OR sport* OR “physical activity”) AND (“gender-based violence” OR “domestic violence” OR “sexual violence” OR “violence against women”) yielded 144 results.

Third, as described in Arksey & O’Malley’s (2005) framework for scoping reviews, we utilized existing networks to identify additional articles that may have been missed in the previous phases. This included discussing with Author 2 and 5 any existing literature, organizations, and conferences related to GBV, TVI, and sport and physical activity, as they have done work in this area. An additional 14 peer-reviewed articles were retrieved based on this phase. The various phases of identifying the literature led to 158 articles being identified for the review (prior to inclusion/exclusion criteria and elimination of duplicates).

Stage 3: Study Selection

For this study, the eligibility criteria for articles included in the scoping review was as follows: (a) Articles published between the year 2000 and August 2022; (b) English language peer reviewed articles; (b) studies that focused on (1) trauma- and violence-informed approach (including trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive practices); and/or (2) served communities with experiences of GBV; and (c) studies using SFD, physical activity (e.g., yoga, exercise), or a sports-based intervention/program. The decision to restrict the language of the study to English was due to the extra time commitment and costs required for translation. The selected timeframe of 2000-2022 reflects the emergence of TVIPA terminology and literature on SFD programs specifically designed for survivors of GBV.

Based on the literature search, a total of 144 articles were identified. After excluding duplicate articles (n=41), Authors 2 and 5 identified additional articles (n=14) that met the eligibility criteria but were not identified in the literature search. Therefore, a total of 117 articles were eligible for review, including those identified in the literature search (n=103) and those identified by Authors 2 and 5 (n=14). The remaining articles were independently reviewed by Authors 1 and 4. Article abstracts that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (n=81). Authors 1 and 4 read the remaining articles (n=36) full-text publications and excluded an additional 15 articles based on inclusion criteria. When uncertainty arose, Authors 2 and 5 determined the final inclusion of an article in the scoping study given their experience and knowledge in GBV, TVI, and sport and physical activity. Following the full article review, 21 peer-reviewed articles remained in the scoping study. Figure 1 summarizes the results of the search strategy and our study selection approach.

Figure 1 – Article Selection Flow Chart

Stage 4: Charting the Data

Authors 1 and 4 entered study information for each article (e.g., title, year/author/region, objective/aim, study population and sample size, method(s), theoretical and conceptual framework, type and duration of study, and terminology used) into a Word document. This table was then used to collate, summarize, and report the results of the scoping review.

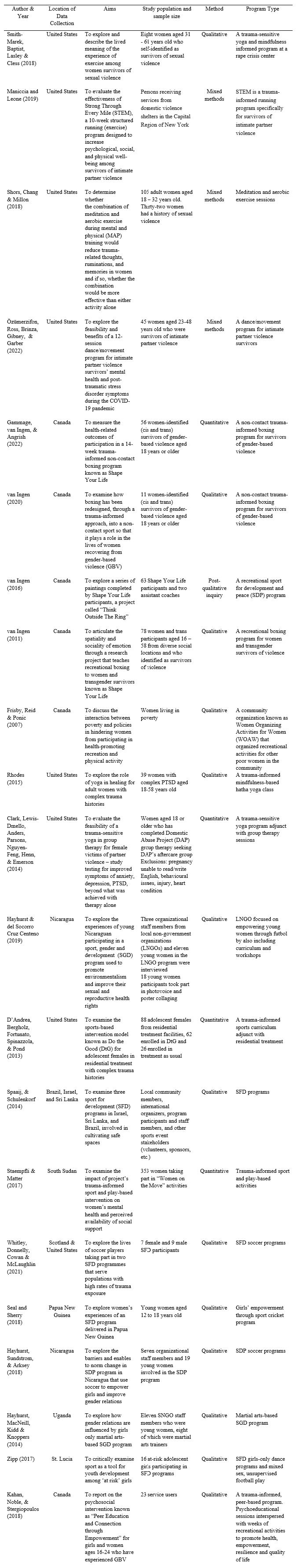

Table 1 – Articles Selected For Review

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

The research team adopted a qualitative thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to summarize the results and findings of the studies included in the scoping review to identify key themes and areas that were similar across studies. The definitions of TVIPA, SFD, and GBV used in the introduction were applied to code studies and identify relevant themes. In the following sections, we outline the results of the scoping review based on Table 1, before discussing key recommendations and ways forward to explore TVIPA and SFD for survivors of GBV.

RESULTS

Below, we describe our most pertinent findings. This includes a description of the articles’ year of study, location, population and sample size, and program type. Thereafter, using thematic analysis, we describe the key delivery elements and shared perspectives of sport for development and TVIPA serving populations experiencing GBV.

Year of Study

The nascent academic interest in TVIPA and SFD programs for survivors of GBV is immediately apparent based on the year of study publication for the articles included in this scoping review. Six studies were published between 2007 and 2014, whereas 15 of the 21 studies were published in the year 2015 or later, pointing to the area of TVIPA and/or SFD programs for people who have experienced GBV receiving increasing attention by researchers. In addition, the study publication date of articles suggests that, since there has been limited work prior to 2010 based on our knowledge of existing literature, the areas of TVIPA and/or SFD for survivors/victims of GBV not only has received recent attention in empirical analysis, but requires more fulsome and in-depth work in the future, particularly given the ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Location of Data Collection

Research focused on TVIPA and/or SFD programs for people who have experienced GBV was almost exclusively conducted by global North researchers, with data collection taking place in both global North contexts (n=13) and global South contexts (n=8). This suggests that despite much of the research taking place in the global South, very few global South researchers are involved in this research. Most studies focused on one geographic location as seen in Table 1 on page 12. Two studies (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Whitley et al., 2021) focused on several geographical areas. What is clear based on the findings is that there are a variety of different geographical locations where work in TVIPA and/or SFD related to GBV is carried out. Each study must therefore be considered contextually based on location and social, cultural, political, and economic norms.

Population and Sample Size

The study populations in this scoping review were also wide-ranging and diverse. Study populations included: women aged 31– 61 who self-identified as survivors of sexual violence (Smith-Marek et al., 2018); individuals receiving services through domestic violence shelters (Maniccia & Leone, 2019); women aged 18–32 with a history of sexual violence (Shors et al., 2018); women aged 23–48 who are survivors of intimate partner violence (Özümerzifon et al., 2022); and women and trans survivors of violence aged 16-58 (Gammage et al., 2022; van Ingen, 2011; 2016; 2020). Study populations also included women with complex post-traumatic stress disorder aged between 18-58 (Rhodes, 2015); women aged 18+ who have completed domestic abuse project group therapy (Clark et al., 2014); and young women in an SFD program (Hayhurst et al., 2014; Hayhurst et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; Seal & Sherry, 2018; Zipp, 2017); adolescent females aged 12–21 in residential treatment facilities (D’Andrea et al., 2013).; and women between the ages of 18 and 40 traumatised by war and violence (Staempfli & Matter, 2017). The sample sizes of studies ranged from 8 to 353 total participants.

Research Methods Utilized

The scoping review revealed that varying research methods are utilized to study TVIPA and/or SFD related to GBV. Qualitative studies (n=12) utilized focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews, observational data, photovoice, field notes, and artwork. Qualitative studies utilized narrative inquiry (n=2), feminist participatory action research (n=1), postcolonial feminist participatory action research (n=1), participatory action research (n=2), community-based participatory action research (n=1), and phenomenology (n=2). Mixed method studies (n=3) utilized pre- and post-test evaluation of the program, focus groups, clinical interviews, and questionnaires. Quantitative studies (n=4) mostly utilized surveys and questionnaires. There was one comparative analysis and one study using post-qualitative inquiry.

Type of Program

Studies in this scoping review investigated a wide range of programs and interventions which varied in duration. In terms of type of program or intervention, the articles included: trauma-informed or sensitive yoga (n=3); trauma-informed and SFD running (n=1); meditation and aerobic exercise (n=1); dance and movement (n=1); trauma-informed and SFD boxing (n=3); local SFD football (soccer) programs (n=4); a multi-sport program including basketball, soccer, and softball in a residential trauma treatment centre (n=1); trauma-informed bi-weekly sport activities (n=1); girls empowerment through cricket (n=1); martial arts (n=1); football and girls-only dance (n=1); recreational-based activities (n=2); and non-competitive multi-sport and games (n=1).

Table 1 – Articles Selected For Review

Thematic Findings: Key Delivery Elements and Shared Perspectives of SFD and TVIPA Serving Populations Experiencing GBV

After conducting a thematic analysis guided by Braun & Clarke’s (2006) approach across the studies included in this review, we identified four prominent themes that aligned with the key tenets of TVIPA and were evident across the 21 articles. This included: 1) understanding the prevalence and effects of trauma and violence; 2) providing safe spaces; 3) offering opportunities for choice and collaboration; and 4) providing capacity-building approaches to support participants.

Understanding the Effects of Trauma and Violence

A trauma- and violence-informed approach ensures program providers understand the prevalence of structural and interpersonal experiences of trauma and violence, and their impacts on peoples’ lives and behaviours (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen et al., 2021). TVIPA requires all individuals in organizations to develop an awareness of how various forms of oppression, such as racism, poverty, and sexism, can marginalize individuals from engaging in physical activity (Darroch et al., 2022a). All 21 studies provided background on the type(s) of trauma and/or violence experienced by participants. Thirteen studies also focused on socio-cultural structures that generate conditions of discrimination and violence, including differing societal and gender norms (Hayhurst et al., 2014; Hayhurst et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; Frisby et al., 2007; Kahan et al., 2018; Seal & Sherry, 2018; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Staempfli & Matter, 2017; van Ingen, 2011; 2016; 2020; Whitley et al., 2021; Zipp, 2017). It is unclear whether all 21 studies addressed both structural and interpersonal understandings of trauma and violence amongst staff and participants, or if these tenets were included solely for contextual purposes. Some studies, such as Seal and Sherry’s (2018) analysis of the ‘girls empowerment through sport’ SFD cricket program, discussed both the structural and interpersonal aspects of GBV. This was accomplished through interactive sessions covering various topics, including self-defence and domestic violence, to increase participants’ awareness of complex issues and encourage critical reflection on personal experiences (Seal & Sherry, 2018). The integration of critical pedagogies in GBV allowed participants to become more aware of broader systematic and structural inequalities such as sexism and poverty (Seal & Sherry, 2018).

In nine of the studies, it was unclear if an explicit understanding of trauma and violence was provided to participants (Hayhurst et al., 2014; Hayhurst et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; Clark et al., 2014; D’Andrea et al., 2013; Oxford & Spaaij, 2019; Rhodes, 2015; Staempfli & Matter, 2017; Zipp, 2017). Eight of these studies clearly discussed how program staff were aware of the traumas and/or violence affecting program participants (Gammage et al., 2022; Kahan et al., 2018; Seal & Sherry, 2018; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Whitley et al., 2021; van Ingen, 2011; 2016; 2020). To illustrate, the “Women on the Move” program targets women traumatized by war and violence in South Sudan (Staempfli & Matter, 2017). The program intersperses group sport activities with group counselling sessions and awareness-raising meetings (Staempfli & Matter, 2017). However, SFD programs that aim to manage post-traumatic symptoms in persons experiencing GBV often refer to these approaches as trauma-informed or trauma-sensitive, rather than using the more nuanced term trauma- and violence-informed (e.g., Kahan et al., 2020; Staempfli & Matter, 2017).

Providing Safe Spaces

The second tenet of a TVI approach is to create emotionally, culturally, and physically safe spaces for service users and providers (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen et al., 2021). Fifteen programs provided safe spaces that embodied different dimensions of safety, including emotional, physical, and cultural (Hayhurst et al., 2014; Hayhurst, et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; Clark et al., 2014; D’Andrea et al., 2013; Kahan et al., 2018; Rhodes, 2015; Seal & Sherry, 2018; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Staempfli & Matter, 2017; van Ingen, 2011; Whitley et al., 2021; Zipp, 2017). For instance, trauma-informed hatha yoga fostered a safe space for participants to claim peaceful embodiment (Rhodes, 2015). This was accomplished by creating new, present-oriented, positive embodied experiences through yoga (Rhodes, 2015). The SYL boxing program provided a social space that enabled survivors and victims of GBV to claim their anger (van Ingen, 2011; 2016; 2020). Interestingly, people who have experienced GBV are often discouraged to express anger or direct it constructively, highlighting the need for more research on emotions and their role in shaping experiences and driving social change (van Ingen, 2011).

Offering Opportunities for Choice and Collaboration

Offering opportunities for participants and staff to make authentic choices through connection and collaboration is an essential pillar to a TVI approach (Darroch et al., 2022a; Wathen & Varcoe, 2021). Twelve studies explicitly discussed participant opportunities for collaboration, choice, and connection with programming (Hayhurst et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; Clark et al., 2014; Kahan et al., 2018; Rhodes, 2015; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Staempfli & Matter, 2017; van Ingen, 2011; 2016; 2020; Whitley et al., 2021; Smith-Marek, 2018). For example, Street Soccer helped participants connect with employment and housing opportunities (Whitley et al., 2021). Further, Street Soccer programming gave participants the freedom to express and process their emotions through conversation and play with other members (Whitley et al., 2021). The PEACE program incorporated a peer-supported and trauma-informed approach, providing flexibility and choice based on participant-identified needs and preferences (Kahan et al., 2020). The Vencer program ensured daily changes in team compositions to reduce competitiveness, and modified rules to vary the physical and emotional demands of the games (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014).

Providing Capacity-Building Ways to Support Participants

The fourth tenet of TVI is to provide strengths-based and capacity-building to support participant coping and resilience (Ponic et al., 2016; Wathen et al., 2021). This tenet emphasizes that programs need to be tailored to the specific needs of the community to reinforce self-care, confidence, and social connections, which subsequently strengthens communities’ abilities to cope with trauma (Darroch et al., 2022a; Darroch et al., 2022b). Sixteen studies provided a strengths-based or capacity-building approach to support participants (Hayhurst et al., 2014; Hayhurst et al., 2018; Hayhurst & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, 2019; D’Andrea et al., 2013; Kahan et al., 2018; Oxford & Spaaij, 2019; Rhodes, 2015; Seal & Sherry, 2018; Staempfli & Matter, 2017; van Ingen, 2011; Whitley et al., 2021; Zipp, 2017; Maniccia & Leone, 2019; Özümerzifon et. al, 2022). For instance, the GET program enabled female staff to assume development officer and managerial roles, as described by participant narratives, which helped build their leadership capacity and increasing their sense of self-efficacy (Seal & Sherry, 2018). Additionally, Street Soccer programming fostered a growth mindset, defined as understanding their abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work, among participants (Whitley et al., 2021). Growth and resilience were recurring themes across players’ narratives, with many seeking new possibilities (Whitley et al., 2021). Trauma-informed hatha yoga also provided capacity-building opportunities for participants, by increasing strengths and capacities through yoga, including their capacity for self-care and emotional and physical intimacy (Rhodes, 2015). On another note, despite the significant and compounding challenges of conducting a virtual dance/movement program during a global pandemic, participants still benefitted from community building through the Zoom chat feature, where they could have side conversations and affirm one another (Özümerzifon et.al, 2022).

DISCUSSION

Using a systematic approach, the goal of this scoping study was to explore peer-reviewed literature on TVIPA and SFD programs targeting populations who have experienced GBV. The scoping review revealed that SFD programs that aim to serve people experiencing GBV were diverse and wide-ranging, underscoring the need for a consistent approach to SFD programs that can be empirically tested and assessed for its appropriateness and feasibility in serving populations experiencing GBV. While considerable scholarship has examined the prevalence of trauma-informed yoga (Darroch et al., 2020), little research has been carried out on the use of trauma-informed approaches outside of yoga, and there is a dearth of research that examines trauma- and violence-informed approaches to physical activity. Scholars have called for an important shift in language by referring to practice as trauma- and violence-informed (TVI), rather than only trauma-informed, to bring into focus acts of violence and their traumatic impacts on victims (Browne et al., 2015; Ponic et al., 2016). And yet, no studies included in this review explicitly used a trauma- and violence-informed approach; rather, studies more commonly employed approaches defined as trauma-informed or trauma-sensitive. However, all studies mentioned specific type(s) of violence impacting program participants, including sexual violence, violence against women, GBV, domestic violence, intimate partner violence and intimate partner terrorism, and complex trauma. Thus, it is essential to consider the context in which SFD and TVIPA programs take place and how different forms of violence compound on each other to uniquely impact program participants. TVIPA offers an approach that can be implemented in SFD and broader sport and physical activity settings to address structural, systemic, and interpersonal forms of violence impacting all program participants, and especially communities experiencing GBV. Literature has suggested SFD programs should foster autonomy-supportive environments that help create a safe and supportive climate for participants (Whitley et al., 2017). Implementing a trauma- and violence-informed approach in SFD programs responds to this need and provides a nuanced approach to best help serve the needs of marginalized communities.

Practical Implications

As evident by this review, working to integrate TVIPA in SFD programs for people experiencing GBV requires the adoption of a multi-sectoral approach in developing a comprehensive GBV prevention and response plan that focuses on the roles and needs of people who have experienced GBV. On another note, this scoping review underlined how SFD programs serving people who have experienced GBV have indeed used many of the tenets of TVIPA (e.g., trauma and violence awareness). These tenets have been useful for ensuring safe spaces and for upholding the agency of program participants. And yet, there remain no SFD programs (that we are aware of) that have yet to formally adopt a TVIPA approach. Organizations and practitioners should thus be particularly interested in integrating the tenets of the TVIPA approach within SFD to ensure that individuals who have experienced GBV will feel comfortable participating in programs (Darroch et al., 2022a).

With the exception of one SFD program, Shape Your Life, programs for people experiencing GBV did not account for gender-diverse social groups, including (but not limited to) transgender, Two-Spirit, queer, gender-fluid, and gender non-conforming people. A TVIPA approach to SFD would thus enhance attention paid to the needs of diverse social identities and prioritize meaningfully engaging gender diverse people in the development and implementation of SFD policy, research and practice. Without upholding the integral viewpoints and lived experiences of gender diverse people, TVIPA and SFD programs serving populations of GBV run the risk of missing the mark entirely and potentially causing more harm than good. For instance, the study conducted by Hayhurst et al., (2014) on a martial arts program in Uganda pointed out that homosexuality is a criminal act in Uganda, and “it seemed dangerous for staff to move away from the heteronormative assumptions that provided justification for their focus on teaching self-defences to only young women and girls” (p. 164). Within communities, substantive discussions need to involve those most vulnerable, which is crucial to amplify voices that critique inequitable gender norms and other oppressive practices.

Given how the pandemic has changed SFD delivery (Dixon et al., 2020), continued efforts should be made to make virtual SFD programming accessible to all, including finding optimal ways to provide the programming on more inclusive virtual platforms (Özümerzifon et. al, 2022). For example, gendered responsibilities, in conjunction with technological barriers like unstable Internet connection and lack of access to digital devices, may hinder the attendance and desired impact of virtual programming interventions (Özümerzifon et. al, 2022, p. 12).

Recommendations for Future Research

Based on this scoping review, we offer five recommendations for future research, policy, and practice related to utilizing TVIPA in SFD programs serving populations experiencing GBV.

First, we suggest that organizations, researchers, and policy-makers seeking to address GBV and using TVIPA in/through SFD to consider the array of populations that are affected by violence, and to work with multiple actors – most especially those who have experienced GBV – in order to more effectively implement programming that suits the needs of particular populations. For example, while community intervention partners are helpful in creating debate within communities about TVIPA, SFD, and GBV, support from local and national actors are needed. Therefore, we particularly advocate for policy-makers to work more closely with community intervention programs to build a multi-sectoral approach.

Second, we suggest that TVIPA training of staff, volunteers, managers, and other program leaders be implemented, especially since many SFD participants may be, or have, experienced violence as evident from the different studies in this review. Training should be context-specific and incorporate the perspectives and suggestions of program participants. This approach enables opportunities of choice, collaboration and connection, as outlined in a TVIPA approach (Darroch et al., 2022a).

The third recommendation is that, SFD organizations should strive to deliver complementary resources that would enable intended participants the ability to fully engage in virtual program activities, such as by supplying user-friendly devices like tablets or computers, reliable Wi-Fi access, and vouchers for childcare services. It is vital for managers and practitioners within SFD to recognize the way in which violence may still permeate virtual spaces. Thus, a TVIPA approach should continue to inform decision-making and delivery of virtual SFD.

Fourth, SFD organizations may consider applying intersectional, anti-oppressive approaches to their work – in line with TVIPA – to better consider how different forms of oppression (e.g., sex, race, class, etc.) contributes to GBV. Notably, only one trauma-informed SFD program included in the review, Shape Your Life (SYL) (Gammage et al., 2022; van Ingen 2011; 2016; 2020), explicitly stated using an anti-oppression framework.

In line with this suggestion, future research may also explore the conceptual approaches and theoretical perspectives being taken up in research on TVIPA in SFD to address GBV. This could involve examining how different theoretical frameworks inform the research on TVIPA in SFD, and how this research can be used to create more effective interventions for GBV. Additionally, exploring theoretical perspectives of intersectionality and how TVIPA can be used as a tool to address the intersectional aspects of GBV may provide valuable insight into how to reduce the incidence of GBV. By conducting further research in these areas, we may be able to develop more effective targeted interventions that address the complex and multifaceted nature of GBV. SYL is one of the few SFD programs that have made efforts to reach out to women in diverse contexts, including immigrant and refugee committees and participants of colour (van Ingen, 2011). In line with TVIPA, SYL aims to address the multiple realities of GBV, particularly facing low-income and racialized women and trans individuals, by offering boxing as a form of anti-violence work within an anti-oppressive framework (van Ingen, 2011). Hence, using an anti-oppressive theoretical framework within TVIPA could aid in holding SFD organizations and practitioners accountable in ensuring that program participants are not homogenized and reflect the multiple realities marginalized communities experiencing GBV face. By expanding our understanding of TVIPA in SFD, we can better address the complex issue of GBV around the world.

Finally, this scoping review highlights the need for future research to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of TVIPA in SFD programs for people who have experienced GBV and in different geographical contexts. Particularly, further research presents an opportunity to investigate how scholarship in the global South is being adopted by global North scholars, and whether these studies involve local experts to ensure cultural and contextual understandings of GBV from an outside perspective.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is the restrictions placed on our literature search including only reviewing articles between 2000 to 2022 and those written in English, however this was the best solution considering costs and time constraints. This scoping review also focused on peer-reviewed literature, omitting grey literature on TVIPA and SFD programs serving survivors of GBV. In addition, inconsistencies with the use of TVIPA, SFD, and GBV terminology may have unintentionally limited the number of articles included within this scoping review – for instance, if terms such as ‘development and sport’ were used rather than SFD. However, such inconsistencies of terminology, including within the studies reviewed, demonstrate the vital need for the adoption and integration of a consistent framework for GBV in SFD organizations and practice, which we have argued throughout the TVIPA approach is appropriate for.

CONCLUSION

This research builds on other recent scoping reviews within the SFD field that examine advancements in the sport for development in relation to Indigenous youth (e.g., Gardam et al., 2017); health promotion interventions in Africa (Hansell, et al., 2021); and health-based programming for women and girls (Pederson & King, 2023). To our knowledge, the study herein is the first study to explore the overlaps and synergies between peer-reviewed literature on TVIPA and SFD programs for victims and survivors of GBV. In turn, this work illuminates the possibilities and potential of TVIPA and SFD programs to work collectively to provide more comprehensive GBV support mechanisms for participants. Based on our findings, we have deduced that – with the exception of one SFD program, Shape Your Life – the exclusion of diverse gender identities in SFD for victims/survivors of GBV has only further entrenched hegemonic ideologies within the sector, with this maintenance of the status quo making a safe space for all illusive. Apart from one SFD program, Shape Your Life, programs for victims/survivors of GBV did not account for gender-diverse social groups, including (but not limited to) transgender, Two-Spirit, queer, gender-fluid, and gender non-conforming people. TVIPA accounts for structural, systemic, and interpersonal forms of violence that has led to the exclusion gender diversity within SFD. Widening whose experience is accounted for is beneficial for everyone and as such programming, research and policy needs to reflect this. Thus, SFD programs can benefit from adopting a TVIPA approach. There are many complexities in how programming was delivered to victims and survivors of GBV, hence there is a need to develop a conceptualized TVI framework that can be utilized across SFD and physical activity programs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

FUNDING

This study was supported by e-Alliance, an initiative of the Gender Equity in Sport Research Hub – Seed Grant, funded by Canadian Heritage – Sport Canada (#1327883), and a York Research Chair (Tier 2) award in Sport, Gender and Development & Digital Participatory Research (Hayhurst).

REFERENCES

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Browne, A. J., Varcoe, C., Ford-Gilboe, M., & Wathen, C. N. (2015). EQUIP Healthcare: An overview of a multi-component intervention to enhance equity-oriented care in primary health care settings. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0271-y

Chawansky, M. (2011). New social movements, old gender games?: Locating girls in the sport for development and peace movement. In Critical Aspects of Gender in Conflict Resolution, Peacebuilding, and Social Movements (pp. 121-134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0163-786X(2011)0000032009

Clark, C. J., Lewis-Dmello, A., Anders, D., Parsons, A., Nguyen-Feng, V., Henn, L., & Emerson, D. (2014). Trauma-sensitive yoga as an adjunct mental health treatment in group therapy for survivors of domestic violence: A feasibility study. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(3), 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.04.003

Collison, H., Darnell, S., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, P. D. (2017). The inclusion conundrum: A critical account of youth and gender issues within and beyond sport for development and peace interventions. Social Inclusion, 5(2), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.888

Cotter, A., & Savage, L. (2019). Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2019001/article/00017-eng.htm

Darroch, F. E., Varcoe, C., Neville, C. (2018). Trauma- and violence-informed physical activity: A tool for fitness and physical activity organizations and providers. Adapted from EQUIP Health Care. Trauma- and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC): A tool for health and service organizations and providers. Vancouver, BC. https://equiphealthcare.ca/files/2019/12/TVIPA-for-women-tool-Nov21.pdf

Darroch, F. E., Roett, C., Varcoe, C., Oliffe, J. L., & Montaner, G. G. (2020). Trauma-informed approaches to physical activity: A scoping study. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 41(3), 101224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101224

Darroch, F. E., Varcoe, C., Gonzalez Montaner, G., Webb, J., & Paquette, M (2022a). Taking “practical” steps: A trauma- and violence-informed physical activity program for women. Violence Against Women. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012221134821

Darroch, F. E., Varcoe, C., Hillsburg, H., Neville, C., Webb, J., & Roberts, C. (2022b). Supportive movement: Tackling barriers to physical activity for pregnant and parenting individuals who have experienced trauma. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 41(1), 18-34. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2022-002

D’Andrea, W., Bergholz, L., Fortunato, A., & Spinazzola, J. (2013). Play to the whistle: A pilot investigation of a sports-based intervention for traumatized girls in residential treatment. Journal of Family Violence, 28(7), 739-749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9533-x

Dixon, M. A., Hardie, A., Warner, S. M., Owiro, E. A., & Orek, D. (2020). Sport for development and COVID-19: Responding to change and participant needs. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.590151

Frisby, W., Reid, C., & Ponic, P. (2007). Levelling the playing field: Promoting the health of poor women through a community development approach to recreation. In P. White & K. Young (Eds.), Sport and Gender in Canada, (pp. 121-136). Oxford University Press

Gammage, K. L., van Ingen, C., & Angrish, K. (2022). Measuring the effects of the shape your life project on the mental and physical health outcomes of survivors of gender-based violence. Violence against Women, 28(11), 2722-2741. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012211038966

Gardam, K., Giles, A., & Hayhurst, L. M. (2017). Sport for development for Aboriginal youth in Canada: A scoping review. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(8), 30-40. https://jsfd.org/2017/04/20/sport-for-development-for-aboriginal-youth-in-canada-a-scoping-review/

Hall, G., Laddu, D. R., Phillips, S. A., Lavie, C. J., & Arena, R. (2021). A tale of two pandemics: How will COVID-19 and global trends in physical inactivity and sedentary behavior affect one another? Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 64, 108–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.005

Hansell, A. H., Giacobbi Jr, P. R., & Voelker, D. K. (2021). A scoping review of sport-based health promotion interventions with youth in Africa. Health Promotion Practice, 22(1), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839920914916

Hayhurst, L. M. C. (2014). The ‘Girl Effect’ and martial arts: Social entrepreneurship and sport, gender and development in Uganda. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(3), 297-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.802674

Hayhurst, L. M. C, MacNeill, M., Kidd, B., & Knoppers, A. (2014). Gender relations, gender-based violence and sport for development and peace: Questions, concerns and cautions emerging from Uganda. In Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, 157-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.07.011

Hayhurst, L. M. C, Sundstrom, L., & Arksey, E. (2018). Navigating norms: Charting gender-based violence prevention and sexual health rights through global-local sport for Ddvelopment and peace relations in Nicaragua, Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(3), 277-288. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0065

Hayhurst, L. M. C, & del Socorro Cruz Centeno, L. (2019). “We are prisoners in our own homes”: Connecting the environment, gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health rights to sport for development and peace in Nicaragua. Sport and Sustainability, 11(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164485

Hayhurst, L.M.C., Thorpe, H., & Chawansky, M. (2021). Introducing sport, gender and development: A critical intersection. In Sport, Gender and Development: Innovations, Intersections and Future Trajectories, (pp. 1-32). London: Emerald Publishing.

Kahan, D., Noble, A. J., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2018). PEACE: trauma-informed psychoeducation for female-identified survivors of gender-based violence. Psychiatric Services, 69(6), 733-733. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.69601

Kahan, D., Lamanna, D., Rajakulendran, T., Noble, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2020). Implementing a trauma‐informed intervention for homeless female survivors of gender‐based violence: Lessons learned in a large Canadian urban centre. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(3), 823–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12913

Kidd, B. (2008). A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society, 11(4), 370-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430802019268

Kidd, B. (2011). Cautions, questions and opportunities in sport for development and peace. Third World Quarterly, 32(3), 603-609. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.573948

Maniccia, D. M., & Leone, J. M. (2019). Theoretical framework and protocol for the evaluation of Strong Through Every Mile (STEM), a structured running program for survivors of intimate partner violence. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6991-y

Mays, N., Roberts, E., & Popay, J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods. London: Routledge.

Oxford, S., & McLachlan, F. (2018). “You Have to Play Like a Man, But Still be a Woman”: young female Colombians negotiating gender through participation in a sport for development and peace (SDP) organization. Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(3), 258-267. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0088

Oxford, S., & Spaaij, R. (2019). Gender relations and sport for development in Colombia: A decolonial feminist analysis. Leisure Sciences, 41(1-2), 54-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1539679

Özümerzifon, Y., Ross, A., Brinza, T., Gibney, G., & Garber, C. E. (2022). Exploring a dance/movement program on mental health and well-being in survivors of intimate partner violence during a pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.887827

Pedersen, M., & King, A. C. (2023). How can sport-based interventions improve health among women and girls? A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064818

Ponic, P., Varcoe, C., & Smutylo, T. (2016). Trauma- (and violence-) informed approaches to supporting victims of violence: Policy and practice considerations. Victims of Crime Research Digest, (9). https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rd9-rr9/p2.html

Rhodes, A. M. (2015). Claiming peaceful embodiment through yoga in the aftermath of trauma. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 21(4), 247-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.09.004

Seal, E., & Sherry, E. (2018). Exploring empowerment and gender relations in a sport for development program in Papua New Guinea. Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(3), 247-257. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0166

Shors, T. J., Chang, H. Y., & Millon, E. M. (2018). MAP Training My Brain™: meditation plus aerobic exercise lessens trauma of sexual violence more than either activity alone. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00211

Smith-Marek, E. N., Baptist, J., Lasley, C., & Cless, J. D. (2018). “I Don’t Like Being That Hyperaware of My Body”: Women survivors of sexual violence and their experience of exercise. Qualitative Health Research, 28(11), 1692-1707. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318786482

Spaaij, R., & Schulenkorf, N. (2014). Cultivating safe space: Lessons for sport-for-development projects and events. Journal of Sport Management, 28(6), 633-645. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0304

Sri, A. S., Das, P., Gnanapragasam, S., & Persaud, A. (2021). COVID-19 and the violence against women and girls: ‘The shadow pandemic’. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(8), 971-973. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764021995556

Staempfli, F., & Matter, D. (2017). Exploring the Impact of Sport and Play on Social Support and Mental Health: An Evaluation of the “Women on the Move” Project in Kajo-Keji, South Sudan. https://www.efdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Exploring-the-Impact-of-Sport-and-PLay.pdf

Government of Canada. (2022, February 7). What is Gender-Based Violence?. Retrieved from https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/gender-based-violence/about-gender-based-violence.html

van Ingen, C. (2011). Spatialities of anger: Emotional geographies in a boxing program for survivors of violence. Sociology of Sport Journal, 28(2), 171-188. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.28.2.171

van Ingen, C. (2016). Getting lost as a way of knowing: The art of boxing within Shape Your Life. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 8(5), 472-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2016.1211170

van Ingen, C. (2020). Trauma and recovery: Violence against women in a neurological age. In M. MacDonald & M. Ventresca (Eds.), Forces of Impact: Socio-Cultural Examinations of Sports Concussion, (pp. 116-131). New York: Routledge.

van Ingen, C. (2021). Stabbed, shot, left to die: Christy Martin and gender-based violence in boxing. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(8), 1154-1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220979716

Wathen, C. N., Schmitt, B., & MacGregor, J. C. (2021). Measuring trauma-(and violence-) informed care: a scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211029399

Wathen, C.N. & Varcoe, C. (2021). Trauma- & violence-informed care (TVIC): A tool for health & social service organizations & providers. London, Canada. https://equiphealthcare.ca/files/2021/05/GTV-EQUIP-Tool-TVIC-Spring2021.pdf

Whitley, M. A., Donnelly, J. A., Cowan, D. T., & McLaughlin, S. (2021). Narratives of trauma and resilience from Street Soccer players. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 14(1) 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2021.1879919

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., & Farrell, K. (2017). A programme evaluation of ‘Exploring Our Strengths and Our Future’: Making sport relevant to the educational, social, and emotional needs of youth. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9), 21-35. https://jsfd.org/2017/09/01/a-programme-evaluation-of-exploring-our-strengths-and-our-future-making-sport-relevant-to-the-educational-social-and-emotional-needs-of-youth/

Whitley, M. A., Wright, E. M., & Gould, D. (2013). Coaches’ perspectives on sport-plus programmes for underserved youth: An exploratory study in South Africa. Journal of Sport for Development, 1(2), 53-66. https://jsfd.org/2014/02/01/coaches-perspectives-on-sport-plus-programmes-for-underserved-youth-an-exploratory-study-in-south-africa/

Zipp, S. (2017). Sport for development with ‘at risk’ girls in St. Lucia. Sport in Society, 20(12), 1917-1931. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1232443