Jairzinho Panqueba1 and Emilie A. Carreón2

1 Universidad Pedagógica Nacional; Universidad Libre, Bogotá, Colombia

2 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Citation:

Panqueba, J. & Carreón, E.A. (2023). Chaaj, Pok-Ta-Pok and Chajchaay: Rubber ballgames from Middle America to the World. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

This paper addresses the modern rubber ballgames of Middle America and traces their genealogy to before the Spanish Conquest. It follows a theoretical framework to register contemporary players’ point of view. On the field, the focus is on recent initiatives materialized in the Maya region of Mexico and Guatemala around the play of three games: chaaj, pok-ta-pok, and chajchaay. Studied from the social sciences and historical anthropology, to confront academic sources arguing the disappearance of the ancient rubber ballgames, it offers a transdisciplinary intercultural assessment of initiatives surrounding their play, emerging from indigenous Mayan communities in the recovery of a worldview that offers a balance between human beings and the natural world.

CHAAJ, POK-TA-POK AND CHAJCHAAY: RUBBER BALLGAMES FROM MIDDLE AMERICA TO THE WORLD

For the Xibalbans desired the gaming things of One Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu their leathers, their yokes, their arm protectors, their headdresses, and their face masks—the finery of One Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu.

– Popol Wuj

INTRODUCTION

Today three rubber ballgames are played in the Maya Region: pok-ta-pok, chajchaay, and chaaj. In the countries of Guatemala, Belize, and the Mexican states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo, pok-ta-pok and chajchaay players strike a solid rubber-ball with a diameter between 6 – 7.5 inches weighing approximately 4 – 8 pounds, squarely with their hip, whereas chaaj players use their forearm to hit a hollow inflatable rubber ball measuring approximately 6.26 inches in diameter. Played in an “I” shaped court, the games feature portable rings set across the short axis. To score in pok-ta-pok and chajchaay, the ball must pass through the double ring suspended 13 feet above the ground, and in chaaj the hollow ball is sent through a vertical ring fixed to a backboard standing at eight feet. These ballgames are currently gaining importance throughout the Maya region and share traits that can be traced to pre-Hispanic models. They find their direct antecedent in ulama de antebrazo (forearm-ulama) and ulama de cadera (hip-ulama), terminology derived from ullamaliztli, the game’s appellation in Nahuatl, the lingua franca of Middle America at the time of the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century.

Figure 1 – Chaaj Game

Note: Mayan forearm rubberball game in the central park of Guatemala City, February 12, 2012. Players from left to right: Erwin Castro Mulul and Jairzinho Panqueba (Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala team), Henry Xalpot Quiej and Jhony Otoniel Rodriguez (Silonem Tijonïk team from the Dirección General de Educación Física of Guatemala). For two periods of 20 minutes each, players pass the ball through the ring (laqäm). The referee (ilonel) keeps track of the scoreboard by adding and subtracting points. This scoring system ensures that during the match, one of the teams always leads the scoreboard. A zero tie only stays until a player scores laqäm. From this single point sum, other scores are by addition and subtraction. Image source: Record file belonging to the lead author.

Figure 2 – Eighth chajchaay championship

Note: Maya hip ball game in the towns of Xesampual, Tzolojyá, Iximulew in the department of Sololá, Guatemala, December 11, 2015. The player Jun Ajchay Josué Cristal (deceased) strikes the solid rubberball with his hip to send it through the ring marker (nupjom). In the foreground José Toc Saloj, from Chaquijyá, acting as referee (Ilonel). Once a player passes the ball through the ring (laqäm), his team automatically wins the game. Image source: Record file belonging to the lead author.

Figure 3 – Hip Strike

Note: The player, Jairzinho Panqueba, performing a hip strike with the solid rubber ball (called: topada or male por arriba), a characteristic move to the play of hip ulama and pok-ta-pok. Shot taken in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, México, during practice on March 17, 2017. Image source: Record file belonging to the lead author.

Contemporary ulama players propel a solid rubber ball with their forearm or hip through a long and narrow playing alley measuring 30.5 yards by 3.28 yards. In arm ulama the ball measures 4 inches and weighs 10.5 ounces and in hip ulama it can measure between 6 and 7.5 inches and weigh as much as 8.8 pounds. The games are played between two teams of three, five, or seven players each, and the method of keeping score is by addition and subtraction. In hip ulama if the ball touches a player’s leg, thigh, knee, foot, hand, head, or above the iliac crest, it constitutes an illegal hit and infractions deduct one point from the score. A point is scored once the team’s players reach the opposite end of the field with the ball.

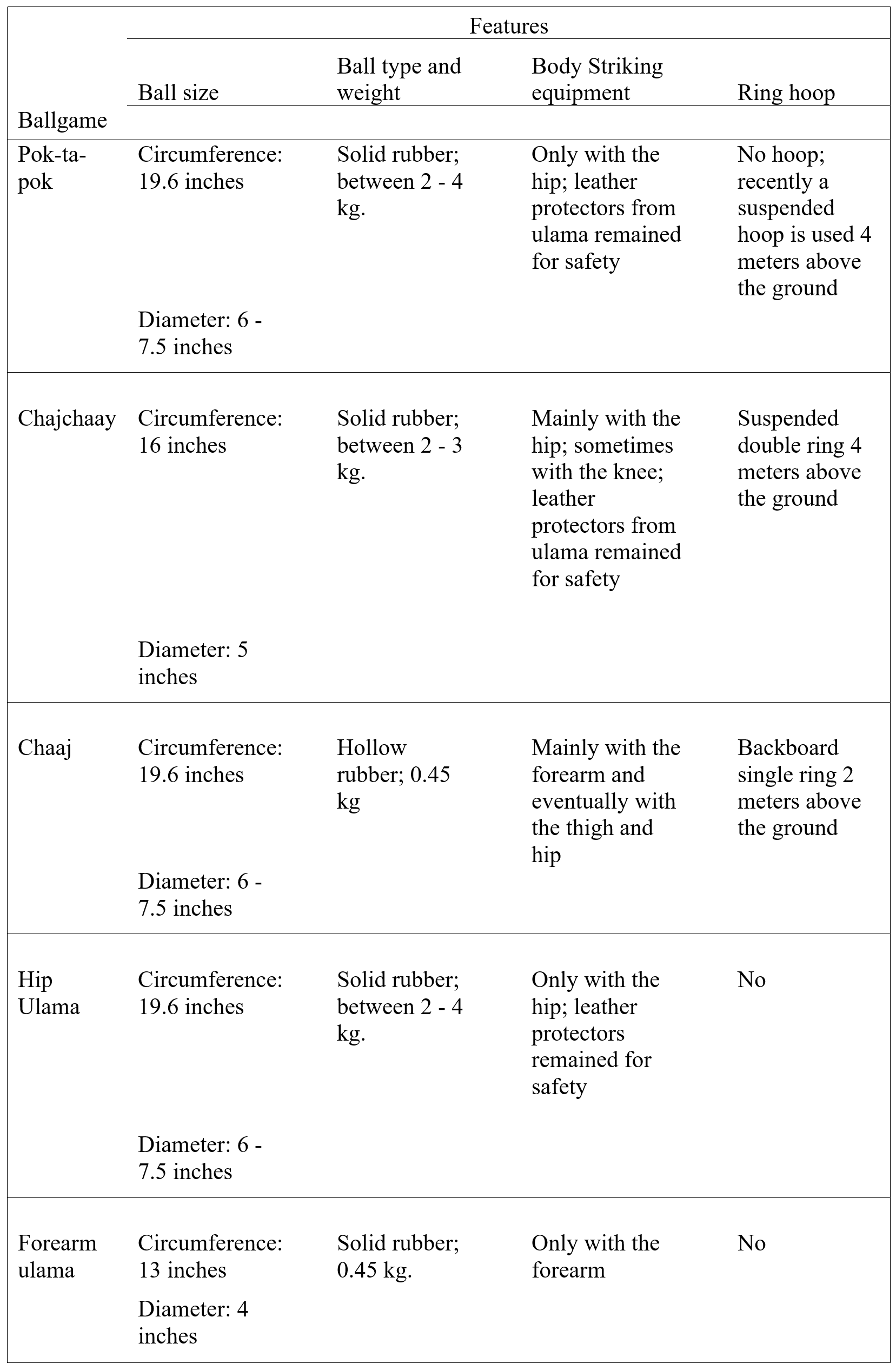

Table 1 – Comparison of Middle American Rubber Ballgames

Forbidden and forgotten, yet preserved in the state of Sinaloa, Mexico where archaeological courts known to date from the beginning of the 7th century are found, ulama passed from the rural rancherias in Northwest Mexico to the Mexican Caribbean in the 1990s, to be showcased in the Riviera Maya. Subsequently it evolved to be pok-ta-pok, chajchaay and chaaj in Southeastern México and Guatemala. In the context of tourism and culture, the games developed in private enterprise, governmental, and non-governmental institutions, as well as through efforts sustained by non-profit movements and organizations and collaborative actions linked to sports and education.

Between 2001 and 2014, the Encuentros Lingüísticos y Culturales del pueblo Maya (ELCPM) incorporated the rubber ballgames to inclusive programs of cooperation between Mayan youths from Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala. This process was framed by ethnic political-cultural movements, characterized as “Pan-Mayism” by academic literature (Fisher & Brown, 1996; Warren, 1998; Watanabe, 1997). In this context, rural and urban Mayan communities in 2010, led by teachers and community leaders, recovered chaaj, pok-ta-pok, and chajchaay as a sport (Panqueba, 2020), a cultural practice (Panqueba, 2012), and exercise fitting to basic education (Panqueba & Pacach, 2019). In 2015, the Asociación de Juegos y Deportes Autóctonos y Tradicionales de Yucatán (AJDATY) and the Asociación Centroamericana y del Caribe del Deporte Ancestral de la Pelota Maya (ACCDAPM) brought together pok-ta-pok players in Yucatán. Subsequently in 2018, the Consejo Superior Universitario de Centroamérica (CSUCA) integrated the play of chaaj as an exhibition game that flourished in Guatemala, and disseminated to other latitudes.

Contemporary expressions of the rubber ballgames are unknown to sports studies and sport for development programs, although their link to ulama has been recognized. Evidence roots the game in Middle Americas’ pre-Columbian past (2500 BC), and research has traced the survival and continuity of the game to Northeast México. Families, historically practicing the game as recreation in rural areas, passed the knowledge from generation to generation, surrounding the elaboration of the ball and the technique and rules of play. Nevertheless, the games’ development in the Maya region has been forsaken by scholarship. It disregards its direct antecedents as well as the nature of the game that germinated in the Riviera Maya in 1990, as promoted by tourism and leisure consortiums, and its repercussions. From this perspective we ask: How were these games transferred from generation to generation despite Academia’s doubts about their authenticity?

Our interest in the Middle American rubber ballgames and their genesis in the contemporary world of sports led to the conformation of an approach that merges archaeological and historical data with ancestral knowledge and the traditional meanings the games hold. As interdisciplinary research, joining the social sciences and historical anthropology, our approach privileges the players’ voices in search of fields where indigenous identity can be ascertained. The theoretical framework strengthening our study (Clevenger, 2017; Vigarello, 2002) contests research that fits indigenous games and sports to concepts and values belonging to Western axiologies (Carreón, 2013), and is methodologically determined by the lead author’s experience and active participation as a player. Focusing on the principles behind the rubber ballgames’ practice, it is interested in describing their play between different ethnicities and identities: their diffusion within contemporary Maya collectivities, sharing a spiritual relationship, and promotion among young players who foster Mayan cultural awareness.

To counter the lack of academic interest in most aspects linked to the contemporary play of rubber ballgames in the Maya Region, this paper presents an overview aimed at recovering their history. It recognizes evolving long-term historical structures linked to them, discusses their common antecedents, and focuses on the nature of their development. It then turns to practical approaches. It reports on the play of the three contemporary rubber ballgames to center on their transmission. In terms of the player’s concepts and sensibilities, it describes the processes linked to the games learned and experienced by the lead author on the playing field.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Permanence of the Rubber Ballgame Until the 1990’s

More than 500 years ago, when Europe reached America, the rubber ballgames she saw, first among the Taino (called batey), and successively among the Totonac, Nahua, Zapotec, Purepecha, Chichimec, and Mayans, did not pass unnoticed. In reports from the end of the 16th century on, they warranted amazement with its play described as never seen movements of the body. Also unique was the bounce of a solid elastic ball made of latex rubber from a tree until then unknown to Europe (Carreón, 2006). Unlike the balls used for European games, America’s volleyed a rubber ball with the swing of the hip, following a singular movement. To portray it, early modern Europeans compared the games they encountered to their own, generally presenting the balls and their corresponding technique of play as a derivation of the games familiar to them (Carreón & Panqueba, 2018).

The conquest destroyed the masonry courts and banned the game’s play (Cervántes de Salazar, 1985; Pomar 1982). In central Mexico, friars and secular priests never saw it played. Nevertheless, between the 17th and 19th centuries, the game is described in historical sources (Stern, 1996) and its practice accounted for. Beginning in the 1930’s and well into 1960’s, its play is reported in Northeast México by scholarly circles (Kelly, 1943). Otherwise, historical references to the rubber ballgames played in the Mayan region are lacking, yet knowledge of their practice survived alongside sacred beliefs during a period of upheaval that would continue into the twentieth century (Martínez, 2014).

The second half of the century saw the hip game in the context of the 1968 World Olympic Games, when players from Sinaloa played an exhibition rubber ballgame in Mexico City (Ramírez Vázquez, 2003), and the search for its antecedents became a research topic (Leyenaar & Penalosa, 1980). The more than 1,500 ballcourts in a region spanning from as far south as Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as the American Southwest were registered (Taladoire, 1981), while interested scholarship came together in a Symposium (Litvak & Castillo, 1972) and presented research surrounding the games’ symbolism, ritual function, equipment, and playing field.

European notions of play and games prevail in modern scholarship when describing the rubber ballgames (Carreón & Panqueba, 2018; Carreón, 2015). The interpretations link them to European games and sports, and to the spectacle surrounding them, particularly soccer (Zarebski, 2016). Presented in the 12th FIFA World Cup, ulama was part of the cultural events staged the summer of 1982 in Spain (Richmond & Mejía, 1982).

Independently, pioneering research begun in 1979 by Roberto Rochin Naya gave way to his filming of Ulama: el juego de la vida y la muerte (1986)1. Documenting the game’s continued play in Sinaloa while highlighting the traditional manufacture of the rubber ball, Rochin collaborated with experienced players from Los Llanitos and Escuinapa, Sinaloa. On their home field the Sinaloan players were filmed wearing regulation ulama equipment; whereas, in the games they played in Maya archaeological ballcourts, passing the ball through tenoned stone rings, they were filmed dressed as players represented on paintings and sculptures of the Maya Classic period (250-900 A.C.).

The film was screened in Mexico City alongside an exhibition game in which ulama players from Sinaloa were showcased in cultural events belonging to the 13th FIFA World Cup. Following, they played in conjunction with the film’s showing at the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City (Castro-Leal, 1986). Four years later, at the 4th Cultural Festival of Culiacan in Sinaloa in 1990, experienced players from Sinaloa presented exhibition games and conversed with an audience of scholars, sharing knowledge about the game their ancestors played (Uriarte, 1992).

Coetaneous, academic reunions on the rubber ballgames took place and their findings were published (Scarborough & Wilcox, 1991; Van Bussel et al., 1991). The festival and film ushered initiatives for the players from Sinaloa to present the game in several venues, mostly sponsored by government initiatives at a state and local level (Turok, 2000). In Mexico City, the interest in pre-Hispanic games would grow to be the Federación Mexicana de Juegos y Deportes Autóctonos y Tradicionales (FMJDAT).

The Rubber Ballgame in the Western Paradigms of Sports and Academia

Taking from Rochin’s film, private enterprise seized the rubber ball game as a commodity in the 1990’s. Grupo Xcaret, a tourism consortium in the Riviera Maya presented a show featuring Mexico’s traditional dances, music, and games: uarhukua ch’anakua,2 and the hip rubber ballgame pok-ta-pok, from the Yucatec Maya verb to ‘play ball’ (Stern, 1996). Working with choreographers, musicians, artists, designers, stage managers, advisors from academia, and players from Sinaloa, some of whom had been in the movie filmed by Rochin, the rubber ballgame was performed in a replica of a ballcourt with retractable rings. As conceived in the film, reformulated in repetition, the game and its players were portrayed as in Maya sculptures and paintings. It was a scenic montage that would conform the game’s representation and fix it in the image of the Classic Maya Period.

Building on Xcaret’s montage, in the 18th FIFA World Cup held in 2006, the rubber ballgame was presented in several German cities. A group of artists and athletes from San Juan Teotihuacán, dressed as Maya nobles, presented a version of pok-ta-pok, striking the ball with their hip and sending it through a portable vertical ring. Unlike the 1968 Olympics, and the 1982 and 1986 FIFA demonstrations in which ulama players had presented the game dressed in the traditional equipment from Sinaloa, the modality pok-ta-pok was now paraded as a primordial form of football.

Stemming from two collective initiatives developed in the Maya region of México, in a parallel manner, pok-ta-pok and ulama were promoted in the field of sports. The first in 2011 in the municipality of Chapab, Yucatán, linked to activities carried out by the AJDATY, supported players traveling to Italy to present exhibitions of uarhukua ch’anakua and pok-ta-pok at the Tocati Festival organized by the Associazione Giochi Antichi. The second in 2018, in Quintana Roo, once entrepreneurs and players from Sinaloa who had performed in Rochin´s film and in Xcaret, established a Mexican federation of hip ulama, the Federación Mexicana de Ullama de Cadera (FEMUC).

The continued involvement of players from Sinaloa, once they stepped off the stage between 1986 and 2014, gave way to the game’s revitalization in its different modalities. Today, in 2023, the practice of rubber ball games, hip, and forearm modalities, finds teams formed in the Mexican states (Sinaloa, Querétaro, Jalisco, Michoacán, Mexico City, Tabasco, Chiapas, Yucatan, Quintana Roo), Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama, as well as in the San Fernando Valley in California and Las Vegas, Nevada. As masters of the hip rubber ballgames, the Sinaloan players’ collaboration with artists, dancers, and players of other sports and games interested in learning to be ulama and pok-ta-pok players, is interconnected to movements born in different latitudes through collective processes and presents the rubber ballgames before new audiences.

Current scholarship, viewing the games’ play from the sidelines, collaborates with official and private initiatives that showcase the game, acting as dynamic advisor to tourism, culture, and sports. Yet its research and publications disregards, and passes judgement on understandings coming from the players themselves. An attitude perhaps explained by the fact pok-ta-pok developed in the context of tourism, and is described as a spinoff, mise en scene or performance, while chaaj and chajchaay, are viewed as simulated varieties of the pre-Hispanic game, judged as lacking authenticity since the game’s unwritten rules are guarded in oral tradition. The rubber ballgames recovered by modern players in the Maya region are harnessed by this understanding. Academia overlooks the relevance of their current play and contemporary players (Rico et al., 1992; Scarborough & Wilcox, 1991; Uriarte, 2015; Van Bussel et al,. 1991; Whittington, 2001). Rather, the diaspora of Sinaloan players as masters of hip play teaching the game in Maya lands has been the object of criticism and mockery in projects that contend it is lost and that they are ‘recovering’ the play of ulama in Northwest Mexico (Aguilar Moreno, 2015; Leyenaar & Penalosa, 1980). The complete lack of understanding of practices that promote game and play further academia’s disregard for the survival and evolution of play with a rubber ball. Misunderstanding, ignorance, prejudice, and discrimination are obstacles to its development, and our review signals their current dynamizations has been overlooked. Its play, linked to local recuperations and evocations belonging to indigenous Maya groups, is hindered by misunderstanding.

METHOD AND ANALYSIS

On the Playing Field of Pok-Ta-Pok, Chaaj and Chajchaay

This research followed a multi-site transdisciplinary approach that recovered testimonies and documents through in-situ ethnographies. Built around shared experiential learning, it engaged players during participant observation. Integrated and developed with community members, players formulated narratives, contextualized in lived experiences. The indigenous origin of the lead author, who is also an athlete and physical educator, allowed him to interact with the players and become an active member/player of the host teams. His cultural knowledge and experience in teaching games and sports were essential to the process.

The players live and work in rural communities, towns, and cities across the Maya region. In their communities they are primarily engaged in agricultural, educational, and community work. At the same time, many find employment in technical and commercial fields, in governmental and nongovernmental offices, or private enterprises involved in cultural promotion, most directly or indirectly linked to not-for-profit, volunteer citizen’s groups organized at a local and national level. Together, to encourage Maya cultural practices and spirituality, they actively participate in the play of rubber ballgames. Their decision to share in our project was strengthened by the biased processes and general disregard they encounter as described above.

In 2011, the lead author teamed up with young Maya players in Guatemala City, searching for a player to join a chaaj team, and other games followed. He encountered players and Mayan officials from the Dirección General de Educación Física (DIGEF), training teachers to play chaaj and promoting its play in school events, and others playing and studying the game. Between 2012 and 2014, procedural material aimed at teaching rubber ballgames and to provide Maya youth with more options regarding sports was developed. In interaction with teachers from 22 regions of Guatemala, he engaged in play with a Mayan teacher then coordinating intercultural programs, and with a Mayan professional who at the time was president of the Chaaj National Sports Association.

In 2014, the lead author encountered chajchaay players from Chimaltenango, Guatemala belonging to the Kukulkan Institute, in a program teaching Mayan epigraphy and vigesimal mathematics, and interested in the revitalization of the ancestral rubber ballgames chaaj and chajchaay in Physical Education curricula. Play continued in Sololá, Guatemala. Training with groups of players, tournaments took place, moreover once members of AJDATY and pok-ta-pok players from Chapab, Yucatán, entered the field.

In the progress of the project the authors consolidated earlier research and in 2015 had the opportunity to work with seasoned players from the FMJDAT promoting the ancestral games and with docents from the Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas (UNICH) promoting chaaj and chajchaay, and training players. One year later, retired teachers belonging to the intercultural educational system (ELCPM), joined our research, and teamwork was strengthened by ulama players from Sinaloa, who had played pok-ta-pok in the Riviera Maya, and by the collaboration of players and sports marketing entrepreneurs in Quintana Roo.

Co-Elaboration in Play

On the field, reflective and effective dialogue moved our play through three paths: contemplation, description, and comprehension. Its organization and activities called for a pedagogy of physical education open to the human experience, as developed in Chinchilla’s study (2005). Thus, integrated into the educational system and joined by players, we explored modalities of learning and teaching in a construction designed around sensory and bodily experiences. Alternate thresholds for teaching and learning to promote the play of ancestral games in pedagogical, artistic, cultural, and academic contexts helped us acknowledge the active and organized promotion of Maya cultural practices that have risen in the field of Mayan spirituality in which the play of rubber ballgames is vital.

The Path of Contemplation

The many interlocutors involved, answering to our eagerness to play and learn, to in turn teach and play modern rubber ballgames, evoked two concepts belonging to the Kaqchikel language: B’ochinïk, which refers to an act of persuasion, and Nik’onïk which relates to super-vision, the ability to be amazed and the emotion brought on by the sight of something extraordinary. The terms transmuted understandings and defined the relationships between the viewer and the viewed, spectators and players, to either interact momentarily and disappear or interact recalling previous experiences, a wonder that transcended and grew to be a memorable experience. Encounters on the playing field in kinesthetic play3 determined the changes as well as the continuities the rubber ballgames’ play sustained, and helped recognize their evolution once transferred from Northeastern Mexico to the Maya Region.

Convened around the ancestral ballgames, bridging cosmogonic and spiritual heritages, players shared their thoughts on the game and engrained memories. Their words brought together and convey the sensitive experience behind the games’ practice. Collected by the lead author, he focused during daily training to learn the games, joined Mayan ceremonies in the development of pedagogical activities surrounding the game, attended team building and tournaments, and learned to make the equipment (attire and balls) needed to play the rubber ballgame in its contemporary modalities.

The Path of Description

Building on the experience lived, to better portray the rubber ball games among the Maya and document the stories surrounding them, the players’ thoughts are woven into this collaborative account. To position their play in contemporary Maya, building on a detailed and critical examination of historical, archaeological, and anthropological sources, an historical path was tracked. It revealed “the presentation of events of the past…is not only objective—according to the actual facts recorded by the observation or in documentary data—but useful for the purposes of political and cultural education” (Fals-Borda, 2002, p. 55B).

The participation from within enabled up-to-date registers of the game, photographic and audiovisual, as well as semi-structured interviews, in which reactions to the game and its play were shared by the players. The exchange of b’ochinïk and nik’onïk (persuasion and amazement) commanded further play, inquiries, conversations, proposals, and discussions between the players and the authors. The encounters evidenced the relevance of women’s participation in the games history (Panqueba, 2016), and revealed their development in the context of Maya communities holding ceremonial and sacred elements linked to self-recognition and identities. They also disclosed the epistemological problems raised by the study and understanding of contemporary ancestral games in Mexico and Guatemala with respect to historiographical sources. Fundamentally, they show that the portrayal of the rubber ballgames derived from academia, saturated by notions belonging to Western games and reaching Maya communities does not accurately represent them, neither as players nor at play in spaces that do not belong to them.

Apprehending the Game

The knowledge gathered on the playing field advanced four lines of analysis: the ethnic experience linked to spirituality, educational opportunity, cultural expression, and tourist management. The procedure followed methods and community components, projected and recognized internationally, implemented to present the rubber ballgames before groups and communities, and to contribute to their dissemination.

Our approach made patent the circumstances and processes that surround their play among contemporary Maya communities. It showed them to be presented as a competition sport, and as a viable physical activity shared by the Maya people, especially the young, while it also advanced the fact that their practice is a source emanating knowledge and ancestral heritage. The approach determined the processes by which the rubber ballgames, as physical education open to the human experience, structured around sensory and bodily experience, are actively used by Maya communities and groups to share ancestral knowledge. It showed the games to be a practice vying for a place alongside sports and games of the West, and conventionally practiced in the world.

Sharing Engrained Memories

The multiple processes and practices that followed our serious play of the rubber ballgames on different courts came together in an exercise, prioritizing an intercultural perspective, able to integrate the many interpretations, understandings, and knowledges of the rubber ballgame as expressed by the players, during the moments of playful interaction. While recording the life stories belonging to the games’ players and promoters, many with no self-ascribed ethnicity, who actively participated in the development of the initiatives to promote the rubber ballgames as a sport, a comparative approach, bearing in mind available historical and archaeological sources on the Ancient rubber ballgames, helped assess the adaptations made to this knowledge and to understand how they developed.

RESULTS: SCORES AND EFFECTS IN THREE MOTIONS

Understanding the notions that envelope the ancestral rubber ballgames to decolonize their practice and rid them from the ignorance and prejudice surrounding them was the purpose of our first exchange. It entailed the analysis of historical and archaeological data and the recognition of the processes that carried the rubber ballgame from Northern Mexico to the Maya region. Only thus did we re-discover the games’ play, enabling us to move beyond stereotypes that bind them, as modeled by academia, sports, and cinema, to play the game in everyday life.

The second exchange determined how once Mayan communities spearheaded manifestations fighting for indigenous and ethnic recognition in Southwest Mexico, their efforts escalated to curtail the appropriation of traditional elements (mis defined as ethnic) and sought to administer the use of elements that characterize Maya art and rituality. Once Mayan indigenous movements evolved and were confronted with the notions that prevail in the games’ presentation as entertainment, linked to sports, culture, and nationalist discourses repeated in school curricula, they took possession of the places for the game’s play, its equipment and attire. In their self-representation, contemporary Maya players followed depictions gathered from portraits of ancient Maya ballplayers to model their play yet channeled them entirely disengaged from the ideal that links the game to Maya nobility and conceived the ancestral community practice as an ancestral sport, instead of as a game.

This is linked to the third movement, the re-claiming and re-learning of the rubber ballgames as nurtured in the Maya region. The process, in the context of physical education, embracing sensory and bodily experiences, was interlaced with ancestral knowledge. It occurred in contexts where imaginaries belonging to ethnic identity are narrated in family histories and personal experiences, and paradoxically engaged in political, economic, educational, and cultural systems.

Yoman Felipe Ilocap, from the Xesampual area, department of Sololá, Guatemala, presents an experience that finds parallels in other player’s understandings and recollections:

I’m 23 years old. I was born to a Catholic family and with the passing of time, they changed world views to the Mayan belief, one year before I was born. At birth I was introduced to Mayan culture, I was not part of any religion; we live the/our/worldview. I began to grow in the culture; that’s why I know all about Nahuales. I work curing and healing animals, I like nature and try to do things that other people don’t do, such as recycling and things like that…I started to play chajchaay in 2007; October 27th was the first time I trained with my cousins who’d been playing for six months with the Sotz’il group. They started teaching us. We played for almost an hour, and for about 15 days I couldn’t walk. It’s not an ordinary game; it’s not like playing football. After a year playing, Tata Lem Mucía Batz began to take us to presentations and performances held in different places. We went to Belize twice, though the third time I couldn’t go because of my job. We also went to Quiché and to other places. People kept staring at us because they didn’t understand it. Then, if it wasn’t my dad, there was another man who explained the game before we started to play so they would understand. They became excited when they touched the (rubber) ball; they were surprised because they imagined that it was an inflatable ball that weighed nothing, because that’s what it looks like.

Insomuch as forms belonging to organized sports show up on the field when teaching and learning of the rubber ballgames, young generations of players in their day-to-day play practice in an atmosphere of Mayan ceremonialism. Ritual activities signal the games’ link to Maya religiousness and spirituality, and anchor the resignifications afforded to them by their present-day practitioners (Panqueba, 2015). Transcendental to the spirituality and ceremonialism imbued in daily observances (cooking, planting, etc.), their play too is linked to Maya ancestrality causal to the preservation of traditions.

Encouraged to play through individual and collaborative efforts, teachers, promoters, and players reactivated the ancestral game. Their words show that it became a catalyst of energies. They composed and structured contemporary rubber ballgame play into the history of their ancestors which in turn enabled players to incorporate their personal generational experience into the Mayan cosmovision and the world surrounding them. By the same token, the ballplayers’ body in play became the means through which to learn the game’s praxis.

Lem Mucía Batz, one of the games’ earliest promoters in Guatemala and author of Chajchaay, pelota de cadera (2004), reveals how personal experiences, described as sensory and bodily, are fostered by ancestral knowledge:

The elders when they speak explain that they are replicating what they saw with their grandparents; it is not only about dialogues but about actions. Then they say b’anob’äl; a word that comes from b’an: fact and b’äl: instrument. This refers to the imitations that are made while following what is done in the dances, the gestures, or the steps we take, which are b’anob’äl. The steps to be followed are not written on a piece of paper, but those who saw the grandfather in action, dancing or in ceremony, repeat it. It is a manner of body code that can be seen, replicated and imitated. This word b’anob’äl is used to name a factor some action of importance that is only seen. Then the son, the grandson, repeats it because he saw it: if I saw it, that’s how it is done. From an exercise he saw, he replicates it. So, I consider it is the replication of a learned code in movement that he reduplicates for his grandchildren to carry on.

While the rubber ballgames became a primary reference, they can be linked to the planting of maize corn, a staple food in the region. In certain occasions, kernels and cobs are exchanged by the representatives of different teams, to bring forth and elevate the moments of play and reciprocity between players that travel from distant localities. They congregate to celebrate a game in the summer and winter solstices, its play an offering presented alongside maize corn, incense, music, dance, and feathers. And in these experiences lived sport, etz’anib’äl,4 is enriched by b’anob’äl, the replication and re-creation of bodily codes, in spirituality, xamanil nimab’ey,5 to play the game of chajchaay.

This practice and concept, b’anob’äl, stands as the basis of the contemporary play and re-creation of chajchaay; it complements and enriches the structures it holds that belong to conventional modern sports, etz’anib’äl. Various processes propel the game’s play in spirituality in a space nimab’älk’u’x, of consultation, gratitude, and learning. Thus, chajchaay championships, ch’akonïk, are not only meant to be where the games’ technical advances are shown and different team’s prowess displayed, nor fields for confrontation and competition, they are where the fabric holding b’anob’äl, etz’anib’äl and xamanil nimab’ey is woven.

In this setting embracing ethnic management, the development set forth by the ELCPM stands out and achieving global recognition for its approach focused on strengthening Mayan languages and cultural manifestations. Its originators, sharing concerns, created the encounters between Mayan People in answer to their experience as teachers working in the bilingual intercultural system, but due personal concerns; their familiarity with the problems disturbing the Maya Region and its people, they lived and witnessed since childhood.

Bartolomé Alonzo Caamal, a retired teacher, professor in the Intercultural Bilingual program in the State of Yucatan and one of the founders of by the ELCPM, explains:

One of our goals…was for a Maya-speaker from Itza, Mopan, or Keqchí, to meet with Mayan people of Yucatan to talk. There were spaces for us to express ourselves culturally and those encounters were the opportunity…Aware of the importance of strengthening the use of our language, the meetings were held in the language of the community, although it had to be translated for speakers of the other Mayan languages. We were pleased to hear the languages expressed…Even though we were all Mayans, our views on the Mayan problem were diverse, but there were also great coincidences; for example, on the importance of strengthening the culture and languages of Maya-speaking communities…José Mucía and Eduardo Takatik from Guatemala, came to [Quintana Roo, Mexico in 1998], to do research with ball players in Xcaret. They came to Valladolid [Yucatan] and looked me up. I was then president of the Mayan Association; we met to talk, and established contact with the idea to continue sharing information and our cultural concerns. Furthermore, Don Valerio Canché Yáh [Yucatecan Maya], a professor of indigenous education, on his part had met people from Belize: Don Angel Sek and the Chayax brothers from Petén [Guatemala]. It was Don Valerio’s idea for promoters, some who already knew each other, to meet in Patchacan, Belize…We got together in 1999…and the hosts were: Don Anastasio Poot´s family and a family named Dzul. Six people from different regions of Guatemala also assisted. We talked for two days. A ceremony was held and from those meetings grew the idea to create the Linguistic and Cultural Meetings for the representatives of the Mayan languages, mainly from Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico, to assist.

The rubber ballgames’ development in the flow of its academization, performance, and management in modern day sports differs from contemporary initiatives that place the ball in the field of education, where its play is generated and administered by and for ethnicities and regulated in educational contexts as a sport as well as a ritual game. As ancestral sports, contemporary rubber ballgames have been heavily tackled, suffering the ideological and symbolic interferences inherited from the historical stages of the development of modern countries where they were once played. Alongside other games coming from the West, such as baseball, Maya people play rubber ballgames and participate in the production of knowledge surrounding them, selecting elements that migrate through time and space, in interpretations, and re-interpretations.

Players in an active manner build on this tradition that signals the games’ link to Maya religiousness and spirituality, and anchors the resignifications their present-day practitioners grant them.6 Spirituality reflected in a constellation linked to Maya ancestrality, daily observances (cooking, planting, etc.), contribute to the preservation of traditions and this is where the transcendence of the play of rubber ballgames rests. In their communities, players are protagonists, taking charge of the ballcourts, equipment and attire, and providing the rubber ball. For the game’s re-creation, suspended portable rings and movable walls holding a single ring are made and ornamented by the players’ community to evoke the pre-Columbian past through fragments of mural paintings preserved in archaeological sites close to their communities, and images from museum catalogues, mass media and scholarly research. While important efforts are being made to set in writing the games’ different rules, some learned from the lips of the players from Sinaloa and others passed on in oral histories of Maya players, the protagonists in teaching the rubber ballgames played by many generations in Middle America recover lost knowledge.

The narratives surrounding the games in play, reflecting ideological and symbolic transformations conceived by official processes linked to the formation and cohesion of the Guatemalan state, a multicultural nation holding a legacy, shared with Mexico, show that, set in motion by Mayan ethnicities and communities, across modern borders, the rubber ballgames became a catalyst of energies. Woven into the history of their ancestors, players incorporated personal narratives to the ancestral games’ contemporary play, which once seized and subjectively apprehended as an sport, provides newfound spaces for the circulation of ethnic consciousness and identities.

Salvador Pacach Ramírez, advisor to the DIGEF, appraises the formation of the Unidad de Interculturalidad of Guatemala´s Ministry of Education to provide a comprehensive physical activity program for schools to promote strong and sustainable growth and create unity in which the role and objectives of play are evident.

One of the Unidad’s primary tasks was to station the cosmogonic meaning of the Mayan ballgame, as related to physical education…It was the government’s aim, with the idea, purpose to promote a sport or game with Mayan identity. So, the intercultural experience as a part of physical education provided the Mayan ballgame with an added value because to playing basketball they said yes, playing football yes, cycling yes, athletics yes, playing chess yes, handball yes, volleyball yes, any of those sports, but none of them as part of Guatemalan culture or in this case Middle America – the vast historical region spanning from Mexico to Costa Rica. From then on, the Maya ballgames’ incursion to physical education gathered strength. That was the objective, whether they thought it up in the vice ministry, or the people brought it here, finally it was part of the task. For example, to identify ethnic, cultural, and linguistic affiliation when carrying out technical, administrative and I think financial processes.

Efforts to revitalize the ancestral game and promote its play in circuits dominated by the games of the West are encumbered by historical chains forged during the conquest and evangelization of America. While the rubber ballgames have been structured in school curricula belonging to Intercultural Universities and practiced in community play in the development of Maya identity in answer to national (Mexico, Guatemala) and local initiatives (Yucatán, Guatemala, Chiapas), mostly presented to identify and determine different indigenous, cultural, and national affiliations, its players and promoters all acknowledge the need to present the game as more than a side show to a spectator sport or as a tourist attraction.

CONCLUSION: PLAYOFF

These games and play described are in fact the reflection of collective wisdoms, immortalized in images and texts belonging to pre-Hispanic America, incorporated into personal narratives and spiritualities belonging to contemporary Maya players. As traditional games, curricula in physical education and as sport, their integration to governmental funded organizations and institutionalization efforts, launched unexpected debates as to the statutes that govern these matters.

Set in motion during ethnic social movements, identities, and traditions, grounded in a shared ancestral, collective, knowledge,7 the rubber ballgames’ play and dynamization faces many paradoxes. The ancestral game forbidden and then exploited to be misunderstood as a spectacle for culture and tourism, it is now played in novel fields belonging to sports and education. In this setting, the ancestral ballgames are exercises relevant to intercultural collaboration and education.

Our position in this paper is to acknowledge that the Maya people, as well as other Amerindians, played games different from those of the West. Its aim is to analyze contemporary rubber ballgames of the Maya as another ritual form presented in their daily life, to understand the reception and resignification of the games’ play and elements (ball, equipment, attire). We look at the games’ play in a context broader than that of mainstream scholarship. Inspired by the exploration of alternate thresholds for teaching and learning, and to encounter the processes behind the promotion of ancestral games in pedagogical, artistic, cultural, and academic contexts, we tracked the play of the rubber ballgames among different groups of players, over an extended historical timeline, to understand their transformations.

Our research shared the sensory and bodily experience of playing the rubber ballgame and making the rubber ball while learning and teaching ancestral knowledge in new contexts. Physical education – more so in intercultural contexts – requires discovering the experience of participation and solidarity, living the sensorial and creative experience while learning (Chinchilla, 2005).Articulated with territorial pedagogy, adopting interculturality as vital to every educational project, the practice, dissemination, and study of ancestral games to educate people and share knowledge is an exercise that brings forth the contemporary emergence of initiatives flourishing in the world. In the context of intercultural education, our project follows paths that will take the games’ spectators and players to feel and think the roots and itineraries of the ancestral rubber ballgames.

This discussion explores a particular pedagogy in the learning and teaching of traditional games, student-teacher projects, and presents the processes behind its development and impact in the Maya region. Flórez Rojas and Mecha Forastero (2020) have found that ancestral practices belonging to migrant communities are endangered by population movements, and our review shows the resettlement of the Maya region had potential consequences on the play of the rubber ball games. In new fields, belonging to sports and education, the rubber ballgames and the ancestral, collective knowledge they hold, conform to unknown conditions. Transformed, their bearers play to preserve spiritual, familiar, and community ancestral knowledge.

Contemporary rubber ballgames have steadfastly followed the path belonging to ancestral practices, sharing knowledge, recuperated, protected, and transformed by commitments with Mother Earth in the development of educational projects (Stócel, 2011), and can be found in intercultural education, in initiatives carried out in geographical, cultural, and social contexts other than those that gave origin to the games.

End Score

Conventional studies on rubber ball games foresee their disappearance (Aguilar Moreno, 2015; Kelly, 1943; Leyenaar & Penalosa, 1980), seldom mention their contemporary play among the modern Maya (Il Joc, 1992; Uriarte, 2015; Whittington, 2001), and often judge it to be a show and consider it a reconstruction (Aguilar Moreno, 2015). Proposals interested in sharing the ancestral game and promoting its play in higher education and matters surrounding it (the balls’ manufacture, the equipment, the games’ sacrality endorsed by feathers, music, dance, the meanings) are often left aside. This epistemic tension challenges the games’ continuity because it essentially disregards efforts born from communities of contemporary players, in this case Mayan, to project and propel their ancestral rubber ballgames. Sharing chaaj, pok-ta-pok, and chaj chaay, players recall lived experiences, replicating and re-creating body codes. As one player noted, “I feel that my ancestors play, borrowing body,” when summoned to the ballcourt. Today in varying contexts, the play of the ancestral ballgame offers Maya communities the opportunity to become part of an evolving cyclical past. Traditional experiences, integrated to daily life linking personal histories, family experiences, and identities, relate the game to a Mayan legacy. An experience contributing to the games’ play where it was once lost, in fields distant from where it was preserved, yet where hundreds of archaeological masonry courts remain. The Sinaloa players’ diaspora and the spread of ulama to the Mayan region contributed to its revitalization. Energized by the events showing it in the Riviera Maya as a spectacle, or as a sacred game in Merida, Yucatan, it is linked to ethnicities and sacrality but also to government-sponsored educational programs where their play recovers and recreates gestures and technical movements. Linked to the performance of sacred Mayan ceremonies in many contexts, today it is played in different scenarios and fields. The kinesthetic practices belonging to ullamaliztli and then to ulama were transported to the Maya region, under the practice of pok-ta-pok, chaj, and chaj chay combining elements belonging to modern sports and the performing arts, while embracing Mayan ancestral processes and beliefs.

Future research will study the rubber ballgames of pre-Hispanic America. However, to better understand the processes that lead to their play in the 21st century and the beliefs that surround them, requires critical analysis. The game, carried from Sinaloa to the Riviera Maya, monopolized by culture, sports, and advertising, sponsored by private enterprise and government programs, advised by academia, has been framed by exhibitions and representations in diverse contexts, and sorely misunderstood. Our research, associated with the social groups and identities that share the games, considers the self-categories operating from different latitudes that bonded, to project and promote its play. It underscores the relevance of the reconfiguration of ancestral games in a globalized world that supports hegemonic sports and sanctions certain corporal practices, yet disregards the play of indigenous games, rooted in tradition, that foster the embodiment of alternative subjectivities.

NOTES

1 In 2010, the film was released in digital version together with a book under the same title. See: Rochin, Solis and Velasco, 2010.

2 A Purépecha ballgame from the State of Michoacán, México; a contemporary practice joining teams and holding tournaments in different regions of the country.

3 Kinesthetic intelligence, which was originally coupled with tactile abilities, was defined and discussed in Howard Gardner’s Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983). In it, he describes activities such as dancing and performing surgeries as requiring great kinesthetic intelligence: using the body to create (or do) something.

4 Neologism adopted to the Kaqchikel language for the concept of sport. The word also translates into Spanish as playing field (Comunidad Lingüística Kaqchikel, 2012).

5 A compound term that denotes spirituality: xamanil (espíritu, spirit) and nimab’ey (camino principal, primary path). It is different to nimab’äl k’u’x, neologism belonging to the Comunidad Lingüística Kaqchikel (2012, p. 125) meaning religion.

6 While this religiousness is reflected in a mythologized vision emerging from Academia, carrying notions of ballplayers and kings, which implied a character and consequences, it is to be found in the formal and aesthetic assimilation by players carrying it out and in the re-signification of certain elements. It is materialized in feathers but also in the imaginaries that in turn, feed artistic production, as well as its reception.

7 Modern science has not validated the existence and importance of a collective knowledge surrounding game intelligence, which provides an open field to explore the promotion of the ancient game as modern sport.

FUNDING

Our research was benefitted by funding from several institutions. UNAM – PAEP grant; Agencia Mexicana de Cooperación Internacional Genaro Estrada grant for Mexicanist scholars; Department of Gender and Interculturality, Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas and Secretaría de Educación Distrital of Bogotá grant. In its final stages it received funding from UNAM -PAPIIT grant IN403619 “Aby Warburg y los estudios precolombinos: reconstrucción historiográfica y desarrollo teórico” and UNAM-PAPITT grant IN106420. “Fabricación de la pelota de hule del juego de cadera mesoamericano. Recuperación de las técnicas a partir de su caracterización material”.

REFERENCES

Aguilar Moreno, M. (2015). Ulama: Pasado, presente y futuro del juego de pelota mesoamericano. Anales de Antropología, 49(1), 73-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0185-1225(15)71645-0

Castro-Leal, M. (Ed.). (1986). El juego de pelota: una tradición prehispánica viva. Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico.

Carreón, E. (2006). El olli en la plástica mexica. Los usos del hule entre los nahuas del siglo XVI. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas.

Carreón, E. (2013). Le tzompantli et le jeu de balle. Relation entre deux espaces sacres. BAR International Series.

Carreón, E. (2015). Cuando los gentil hombres y los salvajes jugaron a la pelota. Anales de Antropología, 49(1), 29-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0185-1225(15)71644-9

Carreón, E. (2013). Le tzompantli et le jeu de balle. Relation entre deux espaces sacres, Oxford, BAR.

Carreón, E., & Panqueba, J. (2018). Del sphaeristerium griego y el harpasto romano al ulamaliztli nahua. In C. Bargellini (Ed.), El renacimiento italiano desde América Latina (pp. 445 – 506). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. http://www.ebooks.esteticas.unam.mx/items/show/55

Cervantes de Salazar, F. (1985). Crónica de la Nueva España. Miralles Ostos.

Chinchilla, V. J. (2005). Elementos sobre epistemología y enseñanza de la educación física. Lúdica Pedagógica, 2(10), 104-112. https://doi.org/10.17227/ludica.num10-7645

Clevenger, S. M. (2017). Sport history, modernity and the logic of coloniality: A case for decoloniality, Rethinking History, 21(4), 586-605. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2017.1326696

Comunidad Lingüística Kaqchikel. (2012). Kaqchikel choltzij, kolon chuqa’ k’ak’a taq tzij. Guatemala: K’ulb’il Yol Twitz Paxi chüqa Kaqchikel Cholchi’ Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala y Comunidad Lingüística Kaqchikel.

Fals-Borda, O. (2002). Historia doble de la costa: El presidente Nieto. El Áncora Editores.

Fisher, E., & Brown, R. M. (1996). Maya Cultural Activism in Guatemala. University of Texas Press. https://doi.org/10.7560/708501

Flórez Rojas, C. A., & Mecha Forastero, B. (2020). Entre el ayer y el hoy: Un estudio sobre las prácticas ancestrales de los Embera – Dobida, a partir de los miembros de la comunidad de Uradá, Quibdó. Colombia. Revista Kavilando, 12 (1), 1-12. https://www.kavilando.org/revista/index.php/kavilando/article/view/377

Kelly, I. (1943). Notes on a West Coast survival of the ancient Mexican ball game. In Notes on Middle American archaeology and ethnology, volume 1. Carnegie Institution.

Leyenaar, T. J. J., & Penalosa, M. M. (1980). Ulama, perpetuación en México del juego de pelota prehispánico: Ullamaliztli. Gobierno del Estado de Sinaloa.

Litvak, J., & Castillo, N. (Eds.). (1972). Religión en Mesoamérica: XII mesa redonda sobre problemas antropológicos de México y Centro América. Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología.

Martínez Gallegos, M. (2014). El ritual del juego de pelota entre los mayas. Desde el posclásico terminal hasta las primeras décadas coloniales. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. https://ru.dgb.unam.mx/handle/DGB_UNAM/TES01000719185

Mucía, J. (2004). Chajchaay, pelota de cadera: El juego maya que maravilla al mundo. Serviprensa.

Panqueba, J. F. (2020). Códices corporales mesoamericanos: Chaaj, Pok-ta-pok y Chajchaay, los ancestrales deportes de pelota maya de cadera y antebrazo en México y Guatemala [PhD dissertation, Posgrado en Estudios Mesoamericanos, Universidad Nactional Autónoma de México. ]. http://ru.atheneadigital.filos.unam.mx/jspui/handle/FFYL_UNAM/2073

Panqueba, J. F. (2016). Mujeres creadoras y jugadoras de la pelota mesoamericana. Entre las complejidades del arquetipo académico y las emergencias actuales de las prácticas corporales. In D. Gay-Sylvestre, Mujeres, derechos y políticas públicas en América y el Caribe, (pp. 23-51). Ediciones del Lirio.

Panqueba, J. F. (2015). Espiritualidades mayas en los juegos de pelota de antebrazo y cadera en el siglo XXI. Pok-Ta-Pok en México; Chaaj y Chajchaay en Guatemala. El Futuro del Pasado, 6, 159-173.https://doi.org/10.14516/fdp.2015.006.001.006

Panqueba, J. F. (2012). Jugadores de pelota maya en tiempos del Oxlajuj B’akt’ún. Lúdica Pedagógica, 2(17), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.17227/ludica.num17-1775

Panqueba, J., & Pacach, S. (2019). Los ancestrales deportes de pelota maya en el contexto educativo de Guatemala. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación y Estudios Interculturales, 3(4), 119-134. https://index.pkp.sfu.ca/index.php/record/view/1374889

Pomar, J. B. (1982). Relaciones geográficas 87 del siglo XVI. Relación de Tezcoco, 8, 45-113. IIA, UNAM, México.

Ramírez Vázquez, P. (2003). México 68-Memoria de los XIX Juegos Olímpicos. Biblioteca Virtual de Cultura Física y Deporte en México, Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte.

Richmond, E., & Mejía, M. (1982). Un antiquísimo juego indígena sigue vivo. México Desconocido, 83, 13-15.

Rico, A., Horta Calleja, G., & Fradley, E. (1992).El joc di pilota al Méxic pre-colombi i la seva supervivènciaa l’actualitat. Fundación Folch.

Rochin, R. (1986). Ulama, el juego de la vida y la muerte. [Film; DVD]. México: Churubusco Azteca.

Rochin, R., Solis, F., & Velasco, R. (2010). Ulama, El Juego de la Vida y la Muerte. Sinaloa, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa.

Scarborough, V., & Wilcox, D. (Eds.) (1991). The Mesoamerican ballgame. University of Arizona Press.

Stern, T. (1996). The rubber-ball games of the Americas. University of Washington Press.

Stócel, A. G. (2011). La educación desde la madre tierra: un compromiso con la humanidad. In F. Gómez Isa & S. Ardanaz Iriarte (Eds.), La plasmación política de la diversidad autonomía y participación política indígena en América Latina (pp. 147-162). Universidad de Deusto.

Taladoire, E. (1981). Les terrains de Jeu de Balle (Mesoamérique et Sud-Ouest des États-Unis). Mission Archéologique et Ethnologique Française au Mexique, Études Mesoaméricaines, México.

Turok, M. (2000). Entre el sincretismo y la supervivencia. El juego de pelota en la actualidad. Arqueología Mexicana, 8(44), 58-65.

Uriarte, M. T. (2015). El juego de pelota Mesoamericano. Temas eternos, nuevas aproximaciones. Universidad Nactional Autónoma de México.

Uriarte, M. (1992). El juego de pelota en Mesoamérica. Raíces y supervivencia. Siglo XXI.

Van Bussel, G., Van Dongen, P., & Leyenaar, T. (Eds.). (1991). The Mesoamerican ballgame. Rijksmuseum Voor Volkenkunde.

Vigarello G. (2002). Du jeu ancien au show sportif. La naissance d’un mythe. Seuil.

Warren, K. B. (1998). Indigenous Movements and their Critics: Pan-Maya Activism in Guatemala. Princeton University Press.

Watanabe, J. (1997). Los mayas no imaginados: antropólogos, otros y la arrogancia ineludible de la autoría. Mesoamerica, 33, 41-72.

Whittington (Ed.). (2001). The sport of life and death. The Mesoamerican ballgame. Mint Museum and Thames and Hudson.

Zarebski, C. (Ed.). (2016). La pelota. Una herencia de México para el mundo. Federación Mexicana de Fútbol A.C. – Cooperativa La Joplin.