Lucy Piggott1, Ingar Mehus1 & Johanna Adriaanse2

1 Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway

2 University of Technology Sydney, Australia

Citation:

Piggott, L., Mehus, I. & Adriaanse, J. (2024). Gender Distribution in Sport for Development and Peace Organizations: A Critical Mass of Women in Leadership and Governance Positions? Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Over the past two decades, a plethora of studies have investigated gender distribution on the boards of national and international sport organizations. However, none of these have focused on sport for development and peace (SDP) organizations. The purpose of this paper was to examine gender distribution across the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations, and the degree to which they have achieved a critical mass of women (a minimum of 30%). We used a quantitative survey in which 118 SDP organizations participated that were diverse in structure and geographic location. On average, the boards and senior leadership teams of the SDP organizations were gender balanced, with 47.71% and 48.92% female representation, respectively. Most organizations had a critical mass of women across their boards, leadership teams, and staff, and there were few differences in gender distribution across continental groupings. Drawing on critical mass theory, the findings imply that women influence legislation, policy, and decision-making within SDP organizations. Furthermore, gender balanced leadership and governance teams likely have a positive impact on SDP organizations’ culture and performance. However, we call for qualitative research to further explore whether women with a seat at the table have a voice to make change within SDP.

GENDER DISTRIBUTION IN SPORT FOR DEVELOPMENT AND PEACE ORGANIZATIONS: A CRITICAL MASS OF WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE POSITIONS?

The sport for development and peace (SDP) sector has developed significantly since the 1990s and has become institutionalized through the establishment and development of distinctive policies, programmes, organizations, funding systems, and partnerships across the world (Collison et al., 2019). SDP is now a key player in the international development sector and there are many hundreds of organizations implementing SDP programmes across more than 125 countries (Giulianotti et al., 2016; Herasimovich & Alzua-Sozabal, 2021). The earliest organizations with a sole focus on SDP were predominantly developed by athletes, physical educators, and sports leaders to either advance peacebuilding and intercultural communication in regions of conflict, or to use sport and physical activity to contribute to achieving the United Nations’ (UN) Millennium Development Goals1 (MDGs) (Kidd, 2008). This means that sport culture, values, and leadership have considerably influenced the development of SDP organizations over time.

Significant diversity exists in the type and structure of SDP organizations, and fully mapping the relations of stakeholders within the field is a challenging and complex task. This is because relations among and between stakeholders lack consistent, linear characteristics and greatly differ in terms of their (in)formality, type, and geographical scope (Herasimovich & Alzua-Sozabal, 2021; Straume, 2019). Additionally, there are no established borders or criteria for organizations to be a part of the SDP sector, but rather the sector is open to all organizations who identify themselves with the aims of SDP (Giulianotti et al., 2016; Lyras & Welty Peachey, 2011). Furthermore, SDP organizations are continuously changing and developing in line with political, economic, environmental, and technological structures and developments (Hayhurst et al., 2011). The pace of growth of the SDP sector makes it challenging to keep track of stakeholders within it (Darnell et al., 2019).

Perhaps due to the lack of existing knowledge on stakeholder relations within the sector, there has been an absence of research examining the decision-making structures of SDP organizations, as well as the demographics of individuals occupying decision-making positions within these structures. This includes an absence of research exploring gender distribution across the governance and leadership teams of SDP organizations. This is somewhat surprising due to the rapid growth of research and applied work being undertaken on this topic within the sport sector. For example, recent research has found a continued and severe underrepresentation of women across the leadership and governance teams and positions of international sport organizations (Matthews & Piggott, 2021). Despite sampling challenges related to such a diverse, expanding, and changing sector, we believe it is important to take the first step in forming an understanding of the extent to which SDP organizations are demonstrating gender inclusion in their leadership and governance structures. This is particularly important when gender equality is placed as one of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and is also identified as one of eight key development goals of SDP by the Sport for Development and Peace International Working Group (The International Platform on Sport and Development, 2021).

The purpose of this paper is, therefore, to be the first known study to present and discuss data on gender distribution across the leadership and governance teams of a diverse sample of SDP organizations. In doing so, we address three research questions:

- What is the gender distribution of the leadership and governance teams and positions of SDP organizations?

- To what degree do the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations have a critical mass of women (a minimum of 30%)?

- What is the impact of the geographical location of the headquarters of SDP organizations (split by continent) on gender distribution on their leadership and governance teams?

Our research questions align with Elling’s (2015) argument of the importance of ‘hard figures’ to numerically examine and monitor gender inclusion across different sporting positions and sectors, and in turn inform the design and development of in-depth research. We believe this is particularly relevant to examine within the SDP field due to its work aiming to make gender equality a lived reality in and through sport (UN Women, 2020). To inform our discussions on gender representation we critically draw upon critical mass theory to both categorize and discuss the implications of our findings in relation to organizational gender power relations (Kanter, 1977).

A note on terminology

It is important to clarify the key terminology used throughout this article as there are some differences in the terminology, roles, and structures of SDP leadership and governance teams compared to those of sport organizations (as outlined by Gaston et al., 2020; Piggott & Matthews, 2021; and others). First, we define SDP organizations as those that intentionally use sport and/or physical activity to engage people in projects that have an overarching aim of achieving social, cultural, physical, economic, or health-related outcomes. The leadership team(s) of an SDP organization forms part of its (part- or full-time) paid administrative hierarchy to oversee different geographic branches or operational areas/departments of the organization. Unlike national sport organizations that typically have one executive leadership team across the whole organization (Piggott & Matthews, 2021), SDP organizations that operate in more than one region or country often have leadership teams overseeing each regional or national branch of the organization. The titles of these teams can vary, including, for example, (senior) management teams, executive teams, leadership teams, co-founders, and operations teams. Leadership teams are usually led by a Chief Executive Officer (CEO) or equivalent at either the national or organizational level to make operational decisions on the delivery of the organization’s strategy.

The governance team(s) of an SDP organization, typically the board, is a part-time voluntary body that is concerned with strategic and financial decisions related to the performance and sustainability of the organization. Some SDP organizations have governance structures that align with those of national sport organizations, where the board is the highest decision-making body of the organization (Piggott & Matthews, 2021). However, not all SDP organizations have a board and, when they do, they sometimes have advisory rather than decision-making responsibilities. Additionally, as with leadership teams, some SDP organizations have numerous boards that tend to govern the different regional or national branches of the organization.

Literature Review

Accompanying the growth of SDP activity over the past two decades has been a significant increase in the volume of research and scholarship conducted in this field. Little research has focused on decision-making structures and positions within SDP organizations, however, and even less has focused on the relationship between gender, leadership, and governance. This is despite a growing body of research on this topic in the sport sector.

Gender, Leadership, and Governance in Sport Organizations

A considerable body of research has been conducted on the topic of gender, leadership, and governance in sport organizations. Within sport governance literature, it has been well documented that there are gender disparities in favor of men at all levels of leadership across sport organizations worldwide (Burton, 2015; Elling, Hovden & Knoppers, 2019; Evans & Pfister, 2021). For example, Matthews and Piggott (2021) recently found that average female representation across the boards of Olympic and Paralympic international federations was just 22%, whilst 21% of the highest leadership positions were occupied by women, and just 5% of the highest governance positions (e.g., chair or president). Such an underrepresentation of women leaders has been found to be the result of a combination of factors at the macro-, meso, and micro-levels, including organizational structure and policy, discrimination, gender stereotyping, gendered organizational culture, and gendered expectations, styles, and behaviors of leaders (Burton, 2015; Elling, Hovden & Knoppers, 2019; Evans & Pfister, 2021).

It has previously been found that geographic variations exist in gender distribution across national and continental contexts. For example, Elling, Knoppers and Hovden (2019) found that Northern European countries such as Norway and Sweden considerably outperformed Southern and Eastern European countries such as Turkey, Poland, and Hungary in terms of mean female representation across the boards of national federations. National politics and culture reportedly played a key role in such variances (Elling, Hovden & Knoppers, 2019). Additionally, Adriaanse (2016) found continental differences in gender distribution across national federations, with Asian organizations having the lowest average female representation across boards, chairs, and chief executives compared to other continental groupings. Additionally, Asia, Europe, and the Americas all had lower than global average female representation across the boards of national federations. Conversely, Oceania was the only continent to have above-global average female representation across all three categories: board, chairs, and chief executives (Adriaanse, 2016).

SDP Governance and Leadership

Governance is concerned with a purposeful effort to guide, steer, direct, control, manage, or regulate the elements of an organization, sector, or society (Hoye & Cuskelly, 2007; Kooiman, 1993). There has been a distinct lack of consideration given to governance within the SDP sector both in applied work and academic literature (Lindsey, 2017). Where literature has discussed SDP governance, the primary focus has been at the macro-level, including stakeholder group relations (Straume, 2019) and SDP governance within particular national contexts (e.g., Lindsey, 2017). At this level of analysis, the influence of international politics, power, policies, and patronage on different stakeholders in the SDP sector have been discussed and critiqued (Giulianotti et al., 2016; Straume, 2019). A small body of work has also focused on SDP governance at the organizational level of analysis. For example, researchers have examined the representation and application of organizational values (MacIntosh & Spence, 2012), motivations of internal stakeholders (Welty Peachey & Burton, 2017), different legal and structural forms (Svensson, 2017), and organizational capacity (Clutterbuck & Doherty, 2019; Svensson & Hambrick, 2016; Svensson et al., 2017). Importantly, these studies have started to explore the influence of governance on the achievement of desired organizational (and sectoral) goals and objectives within the SDP sector.

A key element of SDP governance that has received little attention is governance teams and processes, including the practice, effectiveness, or composition of the boards (or equivalent) of SDP organizations. Boards of SDP organizations often (but not always) lead decision-making on the strategic and financial development and direction of the organization, albeit to different extents across different organizations. Therefore, the ways in which these bodies govern, as well as who is governing them, are important to examine. Clutterbuck & Doherty (2019) found that valued skills and competencies are critical for SDP boards, including relevant educational and professional experience, and expertise in areas such as marketing, communications, financial management, and fundraising. Yet, whilst several studies have looked at the extent to which SDP programming leads to inclusion, there is an absence of research looking inwardly at the extent to which SDP organizations themselves are inclusive spaces that foster diversity within their own decision-making structures. Our study aims to be a starting point for such research in exploring gender distribution across leadership and governance positions of SDP organizations.

In addition to SDP governance, a small body of work has explored leadership and how it is applied within the SDP context. Leadership has many meanings and can encompass, for example, leadership styles, processes, and positions. Within this article, we are interested in leadership in relation to an individual or group having influence over others through social interactions (Western, 2008). Kang and Svensson (2019) highlight the importance of acknowledging environmental and contextual factors when examining leadership within SDP organizations. This is because of the complex and challenging environments in which SDP organizations operate, with SDP programmes often operating in low- and middle-income countries or within poor areas of high-income countries that face particular social, economic, or health-related challenges. SDP organizations also often face environmental challenges, such as resource deficiencies, entrenched social divides, and limited human capital, all of which influence the implementation of leadership strategies (Jones et al., 2018). Therefore, those working within SDP organizations are required to adopt multiple roles to not only implement sport programmes in an instructional capacity, but also address complex social issues (Kang & Svensson, 2019).

In light of such challenges, Welty Peachey and Burton (2017) argue that the style of leadership needed to effectively run SDP organizations may be different to that of sport organizations. This is because the aims and goals of SDP organizations are very different to those of other sport organizations, such as centring around helping marginalized individuals or building trust between groups in conflict (Welty Peachey & Burton, 2017). Such unique leadership challenges within the SDP sector have led to calls for more inclusive leadership to include participants, their families, and broader community members within the decision-making processes of SDP organizations and programmes (Kay & Spaaij, 2012). Researchers have argued that such ‘power-with’/shared leadership approaches are essential for the development of effective and sustainable programmes by allowing for shifts in authority and responsibility, and encouraging community engagement (Jones et al., 2018; Ponic et al., 2010). Overall, this existing literature highlights the unique complexities, paradoxes, and tensions that characterize the governance and leadership of SDP organizations.

Gender and SDP organizations

There is a growing body of research focusing on sport, gender, and development (SGD). This research has included investigations on the gendered experiences of women and girls participating in SDP programmes and initiatives (Caudwell, 2007; Oxford & McLachlan, 2017), case studies of SDP programmes aimed at women and girls (Saavedra, 2009), the use of female role models in SDP programmes (Meier & Saavedra, 2009), and theoretical scholarship examining how gender is represented within the SDP literature (Chawansky, 2011). Scholars have also written about the ‘girling’ of SDP, with SGD initiatives that position girls as the focal points of development increasingly being perceived as ‘trendy’ in international development (Hayhurst, 2011; Hayhurst et al., 2021). Hayhurst et al. (2021) importantly highlight the complex contradictions of SGD in offering tools for empowering women and girls and challenging gender norms, whilst simultaneously having the ability, in some contexts, to act as a catalyst for the subordination, discrimination, and abuse of women and girls.

Only one known study has explicitly analyzed the influence of gendered organizational processes and practices on the experiences of women working in SDP organizations. Thorpe and Chawansky (2017) explored management issues experienced by female transmigrant staff working for the non-governmental organization (NGO) Skateistan in Afghanistan. They found that organizational practices and policies could have positive impacts on gender inclusivity, such as mentoring and gender balance policy, yet highly gendered arrangements of work and leisure spaces was likely a symptom of organizational inadequacy that marginalizes the unique needs and challenges of female employees living and working in a patriarchal society. The isolated nature of this study demonstrates the need for more research on gendered organizational processes and practices within the SDP sector across different cultures and contexts. Furthermore, there remains a clear gap in understanding gender relations in decision making positions in SDP organizations, with no known studies discussing the relationship between gender, power, and decision-making authority in SDP organizations. Our study contributes to this under-researched area of SDP by presenting data on the representation of women within senior leadership and governance teams and positions of SDP organizations.

Theoretical Framework: Critical Mass Theory

The theoretical framework for this study is critical mass theory. ‘Critical mass’ is a concept that has been developed to explain the required relative representation from a minority group on the board of an organization to affect organizational behavior and culture. The basis for critical mass theory is that numbers matter, and women and minority groups are not likely to impact and influence legislation, policy, and decision-making unless their representation grows from a few token individuals into a considerable proportion of decision-makers (Dahlerup, 1988; Konrad et al., 2008).

One of the pioneering authors in developing critical mass theory was Rosabeth Moss Kanter. Her early work focused on the importance of relative numbers of men and women in terms of interaction and influence in organizations (Kanter, 1987). This led her to develop four group types to categorize varying proportional compositions within organizations: uniform, skewed, tilted, and balanced. Uniform groups are those that have members who are (visibly) homogenous and share the same ‘external master statuses’ such as sex, race, or ethnicity. In the case of gender, these are groups made up entirely of men or women. Skewed groups are those in which one ‘type’ is numerically dominant and controls the group and its culture. A male-dominated skewed group is composed of less than 20% women. A tilted group in favor of men has between 20-40% women, meaning that women can begin to affect the culture of the group and can form alliances and coalitions. Finally, gender balanced groups are comprised of a minimum of 40% and maximum of 60% men and women, and the culture of the groups reflect this balance. There is no majority or minority within balanced groups, but the potential for sub-groups to form within and across type-based identifications.

Kanter and others (e.g., Joecks et al., 2013; Konrad et al., 2008; Kramer et al., 2006) have suggested that the threshold, or critical mass, for women to influence the culture of an organization is approximately one third of the board. This is because one or two women on a board are often scrutinized or become hyper visible, and members of dominant groups (i.e., 70% representation or over) can easily marginalize minority group members. On the contrary, when female representation on the board rises to three women or 30%, organizational culture tends to change so that gender is no longer a barrier to acceptance and influence. In these cases, research has found that most (but not all) women tend to feel more comfortable raising issues broader than so-called ‘women’s issues’ (Joecks et al., 2013; Konrad et al., 2008; Torchia et al., 2011). Furthermore, when female representation meets a critical mass, it has been found to have a positive impact on board and organizational culture and performance (Joecks et al., 2013; Konrad et al., 2008; Torchia et al., 2011). For example, Joecks et al. (2013) found that tilted boards outperformed skewed boards across 151 listed German companies over a five-year period (2000-2005). Additionally, Konrad et al. (2008) found that board dynamics shifted to become more collaborative and less contentious when there was a minimum of three women. Furthermore, Torchia et al. (2011) reported that reaching a critical mass of female representation on boards had a positive impact on organizational innovation across 317 Norwegian corporate companies. These findings indicate that it is only after a critical mass is reached that advantages of a more diverse board are experienced, both in terms of organizational culture and performance. Within this paper we critically draw upon critical mass theory to help categorize and analyse our findings in relation to our three research questions.

METHODS

To gather data on the representation of women across the leadership and governance teams of a diversity of SDP organizations, we used a quantitative electronic survey to allow organizational representatives to self-report gender composition as well as information on several other organizational characteristics.

Sample and recruitment

An email list was created of individuals representing 539 different SDP organizations from a database developed by The International Platform on Sport and Development (sportanddev), as well as professional contacts of the first author who represented a further 16 SDP organizations. Sportanddev is “the leading global hub for those using sport to achieve social, economic and environmental objectives” (The International Platform on Sport and Development, 2023, para. 1). It operates an online platform that shares news, information, and resources in the sport for development field, as well as supporting and coordinating events, advocacy, and other initiatives (The International Platform on Sport and Development, 2023). Sportanddev developed their database of SDP organizations to collate information on all organizations registered on the sportanddev online platform (sportandev representative, personal communication, November 19, 2020). The contacts for organizations in the sportanddev database mostly occupy the role of founder or CEO, but some occupy other leadership or administrative roles. The first author’s professional contacts held different leadership roles within their organizations.

Initial emails inviting the 555 organizations to participate in the electronic survey were distributed via mail merge. 108 of these emails were undeliverable, meaning 447 organizations were contacted via email. A second reminder email was distributed to organizations who had not yet participated in the survey two weeks after the initial email was sent. In addition to the invitation emails, a call for participation was also distributed via the social media channels of sportanddev, Beyond Sport, the Sport for Development Coalition, and the first author, as well as via articles on the sportanddev and Sport for Development Coalition websites, and via the Sport for Development Coalition newsletter. A total of 121 organizations participated in the survey, but only 118 of these could be included in the final data set due to missing or incomplete data. Due to the open call for participation in addition to the mailing list, the response rate is unknown.

The selection criterion for the survey was simply that respondents must represent an SDP organization to participate in the research. Specifically, an SDP organization was defined as an organization that intentionally uses sport and/or physical activity to engage people in projects that have an overarching aim of achieving social, cultural, physical, economic, or health-related outcomes. At the start of the survey there was a compulsory question asking respondents to confirm that the organization they were representing met this description. The responses were checked thoroughly to ensure that no duplicate responses were submitted by different individuals from the same organization.

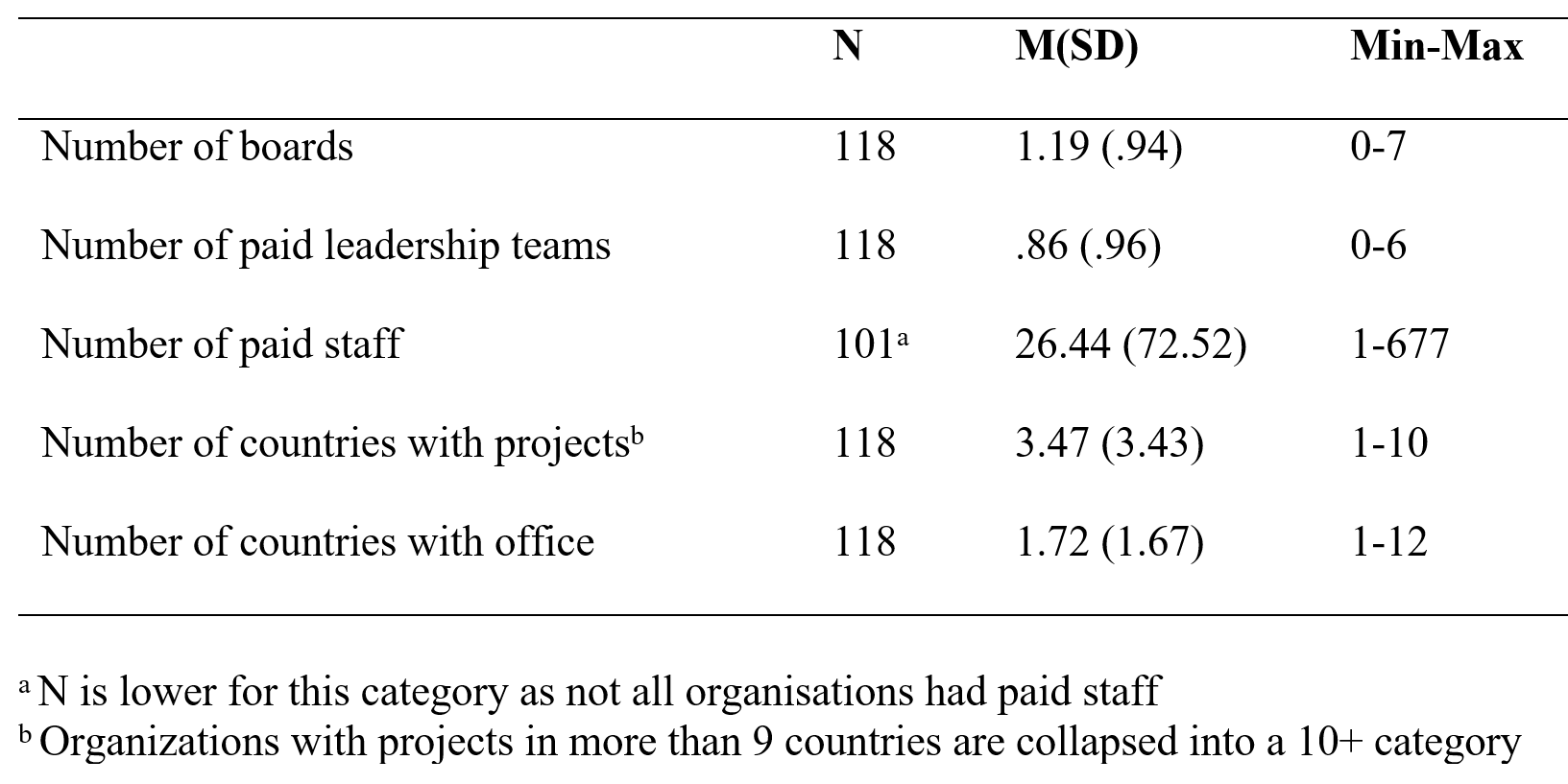

The survey sample was diverse in terms of the locations and characteristics of organizations included. Six continents were represented: Africa (n=26), Asia (n=22), Europe (n=44), North America (n=15), Oceania (N=3), and South America (n=8). Some key characteristics of our sample related to organizational structure are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 – Key characteristics of sport for development and peace organizations (N=118)

As shown in Table 1, the organizational characteristics of the SDP organizations that formed our sample are extremely diverse. For example, the paid workforces of the organizations ranged from one to 677 employees, the number of countries within which projects are operated ranged from one to over 10, and the number of countries within which organizational offices are located ranged from one to 12. Similarly, the leadership and governance structures of SDP organizations are extremely varied, with the number of boards ranging from zero to seven, and the number of leadership teams ranging from zero to six. The diversity of our sample reflects the diversity and complexity of the broader SDP sector and was a key reason for an electronic survey being our method of choice for this study. This is because there is no exhaustive list or database of SDP organizations to track or monitor, as is the case within the sport sector with distinct organizational groups such as national or international federations. Additionally, there are no uniform leadership and governance structures of SDP organizations, as is the case with most sporting bodies. Furthermore, the information provided on the websites of SDP organizations (such as the individuals who comprise their workforces and leadership and governance teams) is extremely varied. Therefore, without self-reporting, it is challenging to identify and name the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations, let alone their gender distribution.

Instrumentation

The electronic survey consisted of 17 compulsory questions that included a focus on the following organizational characteristics: age, location of the headquarters, offices and projects, number of countries that projects are operated in, annual income, number of paid staff, number of boards and leadership teams2, and gender composition of the board(s), leadership team(s), chair of the board(s), and most powerful leadership position on the leadership team(s). Decisions on the relevance and importance of the organizational characteristics included in the survey were based on the literature and discussions with experts in the field.

After being asked to report on whether their organization has at least one board or leadership team and, if so, how many boards/leadership teams they have, the organizational representatives were asked to provide the name/title of the board(s), leadership team(s), and most powerful position on each leadership team before inputting the gender composition of these teams and positions. This was firstly to ensure understanding from the respondents on the information they were being asked to provide, and secondly to gain an understanding of the different roles and titles of these teams and positions across different organizations. The titles and roles of boards included boards of trustees, advisory boards, boards of directors, executive boards, international boards, and national boards. Additionally, the titles and roles of the leadership teams included (senior) management teams, strategy teams, executive teams, leadership teams, co-founders, and operations teams. Finally, the most common titles for the most powerful leadership positions were Chief Executive Officer, Chief Operating Officer, Executive Director, General Manager, Director, and Managing Director. This again shows how diverse SDP organizations are in their organizational terminology and structures.

There was a particular focus on collecting compositional data across leadership teams, powerful leadership positions, boards, and chairs of boards due to these teams and positions holding substantial leadership, managerial, and/or decision-making influence within their organizations. We were, therefore, interested to understand the extent to which the teams and positions with most strategic, financial, and operational influence within SDP organizations were gender balanced.

Quality of the research

To increase the quality of the research, prior to the design of the survey, informal conversations were held with 11 individuals (four women and seven men) working within the sector across a range of roles to better understand the sector, its structure, and its challenges. Additionally, before the survey ‘went live’, a draft of the survey questions was distributed to four experts (two women and two men) within the SDP field, who included two academics who had also previously worked within SDP organizations, a practitioner currently working for an SDP network, and a practitioner currently working for an SDP NGO. These individuals had expertise and experience of working with organizations across all continents. The purpose of this exercise was to obtain feedback on the language/key terms used within the survey to ensure that it would be understandable and relevant to all respondents regardless of their location, as well as the content of the survey to ensure that the organizational characteristics being explored were most relevant for the sector. The survey was re-drafted multiple times based on the feedback and suggestions of these individuals.

Whilst steps were taken to increase the quality of the research, there were still some limitations to the approaches taken. As already mentioned, we relied on the sportanddev platform for the main source of our sample. This platform has previously been reported to be dominated by organizations from the Global North (Herasimovich & Alzua-Sozabal, 2021) and sportanddev themselves recognise that some regions (e.g., East/Southern Africa, Europe, and South Asia) are better represented than others (e.g., Latin America and West Africa) (sportanddev representative, personal communication, November 19, 2020). This may, therefore, have had an impact on the organizations that formed our sample. Our final dataset was, however, completely balanced across the Global North and Global South (n=59 for each category). A further factor that may have skewed our sample was the combination of this platform operating in English as well as the survey being written in English. This could have excluded some organizations whose staff work in non-English languages. The self-reporting nature of the study should also be noted, with potential for bias amongst the respondents if organizations with poor female representation felt less inclined to participate in the study.

We decided not to gather information on other social characteristics of SDP decision-makers such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability status, and age. We recognize that the absence of such data provides a one-dimensional picture of gender representation across SDP organizations (failing to account for intersectional differences), but it was deemed unreasonable to expect survey respondents to know or spend time inputting this information on behalf of all those occupying decision-making positions within their organizations. This is because many social identity markers such as sexual identity, ethnicity, social class, and some forms of disability are not visible and so may not be known by the respondent. Finally, it should also be noted that gender-related data was reported according to the gender that respondents either knew or perceived individuals in their organization to identify with. Therefore, there could have been some examples of misgendering if respondents were not aware of transgender or non-binary identities amongst colleagues within their organization.

RESULTS

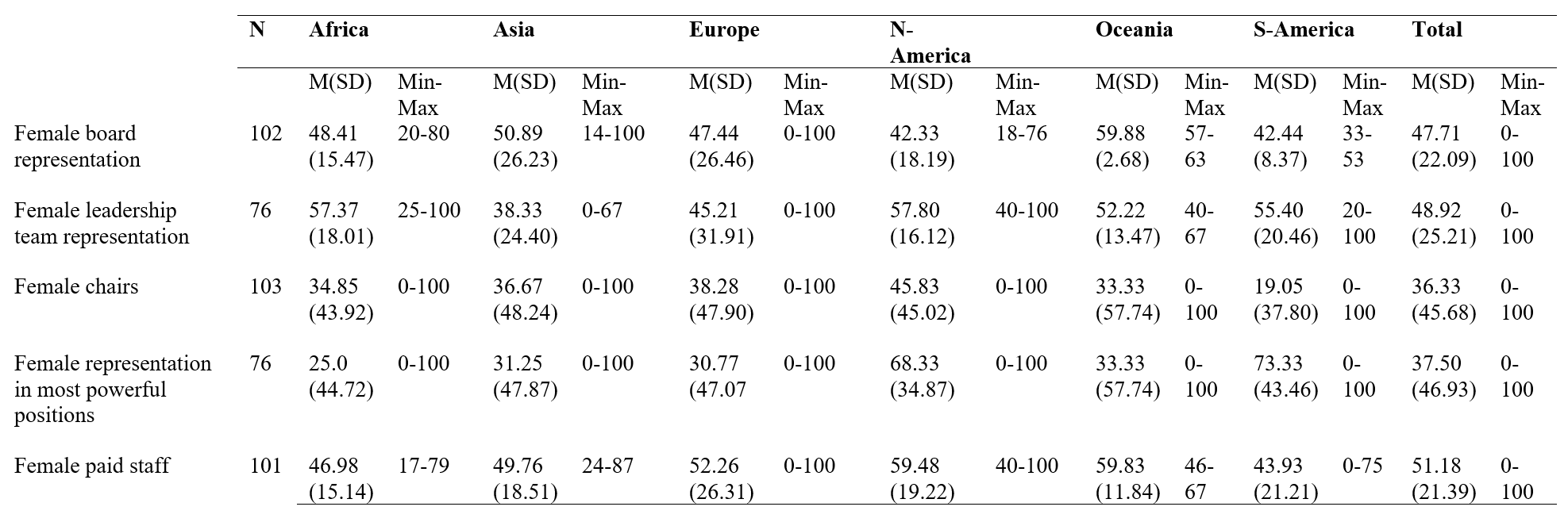

Table 2 presents percentages of women across the leadership and governance teams and positions of the 118 SDP organizations that form our sample. It is important to note that the category ‘female’ includes all of those who were known or perceived to identity as female or a woman (including both cisgender and transgender women). Across the paid employees of all 118 organizations (n=3896), only three individuals were reported as being non-binary (0.0008%). Furthermore, there were no non-binary individuals reported to be on the boards or leadership teams of the organizations included in our sample. This demonstrates an overall lack of gender diversity outside of the male-female binary across SDP organizations and highlights a topic that deserves attention in future research.

Data presented within Table 2 are split by continent. As highlighted in our literature review, the geographic location of an organization has been found to have significant influence on both gender distribution and organizational culture in the sport sector (Adriaanse, 2016; Elling, Hovden & Knoppers, 2019). We were, therefore, interested to see if such geographic trends extend to gender distribution across the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations.

Table 2 – Percentage (%) of female representation in board, leadership, and staff positions in sport for development and peace organizations by continents

Findings in Table 2 demonstrate that overall, on average, the SDP organizations in our sample are gender balanced across both their boards and senior leadership teams (47.71% and 48.92% female representation, respectively). These figures are slightly lower than average female representation across the paid workforces of the organizations (51.18%). It is notable that the standard deviation of female representation across the boards and leadership teams were high (22.09 and 25.21, respectively), showing diversity in female representation on the boards and leadership teams of different SDP organizations. Additionally, the range of female representation across the governance and leadership teams of the organizations was very extreme, ranging from 0% to 100% across both categories. This means that some SDP organizations have uniform boards and leadership teams that are either completely made up of men or completely made up of women. Ten organizations had uniform representation across their boards, and all these organizations had just one board. Of these 10 organizations, seven organizations were uniform in favor of women (100% female representation) and three organizations were uniform in favor of men (100% male representation). Fourteen organizations had uniform representation across their leadership teams, and again all these organizations had just one leadership team. Of these 14 organizations, six were uniform in favor of women (100% female representation) and eight were uniform in favor of men (100% male representation).

On average, the organizations are tilted in favor of men in terms of gender distribution across both chairs of the board and the most powerful leadership positions (36.33% and 37.50% female representation, respectively). The standard deviation and range across these categories were high (45.68 and 46.93, respectively) due to the nature of these positions either being occupied by a woman (100% women, 0% men) or a man (100% men, 0% women). Vertical gender segregation can be seen here, with average female representation reducing by over 10% when moving from general board or leadership positions to the most powerful positions on these teams.

When examining female representation across continental groups, some geographic trends can be seen. For example, the leading continent for female representation was either North America or Oceania across every variable presented. That said, North American organizations had the lowest average female representation on boards out of the continental groupings (42.33%). Additionally, whilst organizations from Oceania had high female representation across variables related to groups or teams, there was a significant reduction (of between approximately 19-26%) in female representation relating to individual positions of power (Chair and most powerful leadership position), demonstrating vertical gender segregation. Organizations from South and North America had particularly high female representation across the most powerful leadership positions (73.33% and 68.33%, respectively) compared to the other continental groups which were all below 38%.

No continental groups had low female representation across multiple variables, but two individual results stand out as particularly low female representation in relation to a single variable. First, there was only 25% female representation across the most powerful leadership positions of the African organizations that formed our sample. Second, there was only 19.05% female representation across the Chairs of organizations located in South America. It is notable that both of these variables relate to the most powerful positions within the organizations, aligning with research that has found a significant underrepresentation of Presidents, Chairs, and CEOs (or equivalent) across sport organizations worldwide (Adriaanse, 2016; Matthews & Piggott, 2021). It is also observable that Europe was the only continent to have examples of organizations with no women on their paid workforce, board(s), and/or leadership team(s).

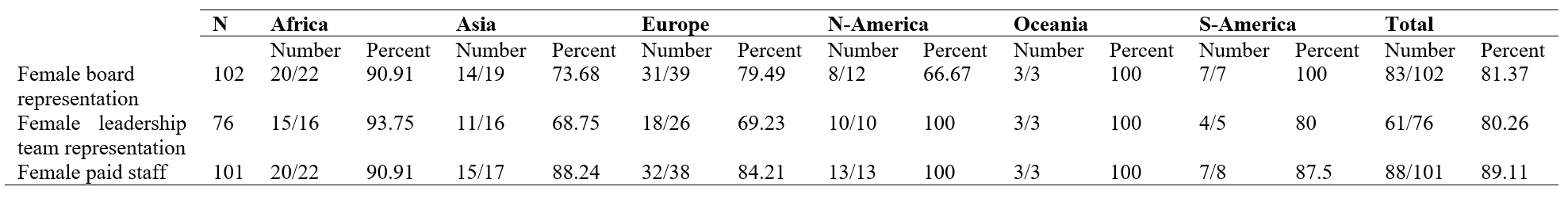

Table 3 shows the number and percentage of organizations that have a critical mass of women across their board(s), leadership team(s), and overall paid workforce. Chairs and most powerful leadership positions are not included as they relate to just one position within an organization, rather than a team/group.

Table 3 – Number and percentage (%) of sport for development and peace organizations reaching critical mass (30%) of female representation

Most of the SDP organizations had a critical mass of women across their paid workforce, leadership team(s), and board(s). Slight vertical gender segregation can be seen here, with a higher proportion of organizations having a critical mass across their whole paid workforce compared to their boards and leadership teams. Some geographic trends are visible when examining the number and percentage of organizations reaching critical mass across different continental groups. Notably, Oceania was the only continent where all organizations had a critical mass of women across their paid staff, boards, and leadership teams. This aligns with findings in the sport sector, as outlined in our literature review (Adriaanse, 2016). The small sample size of organizations in Oceania (n=3) should be considered, however. Additionally, a high proportion of African organizations achieved a critical mass of women, with over 90% of organizations achieving critical mass across all three variables. There were no notably low results according to continental grouping, with every continent having over 66% of organizations achieving critical mass across all variables.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our findings present a positive picture of gender representation across the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations. The boards and leadership teams across our sample were, on average, gender balanced. Additionally, most organizations had a critical mass of women across their workforce, board(s), and leadership team(s). Furthermore, there were few notable geographic trends in gender distribution across the organizations. There were some isolated examples of continental groups having particularly high or low female representation relative to other continents across some variables, but no continents had consistently and significantly higher or lower female representation across all variables. Within this section, we critically draw on existing literature and critical mass theory to discuss two key themes in relation to these findings:1) differences in gender distribution trends across the SDP and sport sectors, and 2) the impact of our findings for real world practice across the SDP sector.

SDP vs Sport: Exploring Differences in Gender Distribution

The overall high proportion of women across the boards and leadership teams of SDP organizations is in stark contrast to recent findings of continued low female representation across the boards and leadership teams of sport organizations (Matthews & Piggott, 2021). This is particularly interesting when there has been a notable increase in recent decades in the implementation of policy and actions to increase the representation of women on the boards of sport organizations at the national and international levels. Such policy has typically been implemented by national sport councils, international federations, or international governing bodies such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and International Paralympic Committee (IPC) that hold governing power over other organizations (e.g., IOC, 2018; IPC, 2017; Sport England & UK Sport, 2016). Conversely, due to a lack of overarching organizations within the SDP sector that hold governing power over other SDP organizations, there has been a lack of sectoral- or regional-level policy related to gender representation in SDP leadership and governance. Some international SDP funding organizations, such as Laureus, require organizational gender representation statistics to be presented within funding applications, but applications are not accepted or rejected based on this. Instead, advice and guidance are provided to organizations with poor gender representation (Laureus employee, personal communication, January 15, 2021).

Within this context, the question is raised of why our sample of SDP organizations have considerably higher female representation compared to sport organizations. Drawing on literature across SDP and sport leadership/governance, we argue that a key influencer could be differences in the aims, values, and structures of organizations across these sectors. For example, sport organizations such as national and international federations measure much of their organizational success on results and performance within their sport, particularly at the highest level. The receipt of public funding or sponsorship is also largely based on sporting performance and the resultant public popularity. Such formal, organized sport participation and competition has, since the very beginning of sport codification, been based on gender binary classifications that have developed an essentialized differentiation between women and men (Pape, 2020). Although leadership positions in sport are purportedly not based on physical sporting qualities, qualifications for positions of sport leadership often require the applicant to have a sport history (Knoppers et al., 2021). Such factors have led to the argument that “images and discourses associated with management and leadership in sport are infused with masculine traits and characteristics such as toughness, sport playing experience, and instrumentality” (Schull et al., 2013, p. 59). As discussed within the literature review, a significant body of research has reported that processes and practices of sport organizations have created barriers and challenges for women leaders within the sector at the macro, meso, and micro levels, including structural, cultural, and individual factors.

Contrastingly, the purpose of SDP organizations is to use sport as an intervention tool to achieve goals that are wider than sport and sporting objectives (Giulianotti et al., 2016). Within our project, we have defined SDP organizations as those that use sport and/or physical activity to engage people in projects that have an overarching aim of achieving social, cultural, physical, economic, or health-related outcomes. This means that the goals of these organizations are very different to those of other sport organizations, such as centring around helping marginalized individuals, building trust between groups in conflict, and achieving social change (Welty Peachey & Burton, 2017). Furthermore, many SDP organizations explicitly work to make gender equality a lived reality through sport-related programmes, particularly in working towards the UN’s fifth sustainable development goal: gender equality (UN Women, 2020). This can include programmes working to address gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive health education and rights, and female educational and economic empowerment (e.g., Women Win, 2022). SDP organizations operate within complex and challenging environments, and so those working within SDP organizations are required to adopt multiple and diverse roles that cross the boundaries of leadership, project management, people management, education, and mediation (Kang & Svensson, 2019). This range of factors indicates that so-called ‘feminine traits’ such as emotional intelligence, empathy, and care, are more congruent with the leadership requirements of SDP organizations compared to the so-called ‘masculine traits’ that sport organizations have been aligned with (Schull et al., 2013). Furthermore, due to the aims and goals of SDP organizations, it would be expected that most of those working in, and leading, SDP organizations place high value on inclusivity, equity, and social change. The cultures and structures of SDP organizations are, therefore, more likely to be inclusive, equitable, and dynamic compared to the sport sector, and so more conducive to gender balanced and equitable leadership and governance teams.

Another notable factor that has been discussed in the sport governance literature is the substantial prestige, as well social and economic benefits, that are attached to sport leadership and governance positions (Gal & Foldesi, 2019; Hovden, 2010; Piggott & Matthews, 2021). Research on sport organizations has found that the proportion of women decreases as power and prestige increase, either in terms of position or organization (Claringbould & Knoppers, 2008; Piggott & Matthews, 2021). Notably, the two organizations widely regarded as the most prestigious sport organizations – the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and FIFA – have never been led by a woman. Additionally, in many cases female representation is lower in more prestigious international federations compared to national federations (Adriaanse, 2016; Matthews & Piggott, 2021). Furthermore, low female representation in the most senior and respected sport leadership positions has led to a gender pay gap within some national contexts (e.g. Velija, 2022). Conversely, most SDP organizations are relatively unknown on the global or even national scale, meaning that leadership and governance positions within most SDP organizations hold limited prestige. Therefore, the lack of opportunity for SDP leadership and governance positions to wield capital in the forms of prestige and wealth may be a further factor in more gender balanced and inclusive organizations.

Finally, the lack of notable geographic differences in gender distribution across continental variables is also in contrast to what has previously been observed within the sport sector (Adriaanse, 2016). Across national sport organizations, political and cultural differences have resulted in varying levels of gender distribution and equity (Elling, Hovden & Knoppers, 2019). However, unlike most national sport organizations, SDP organizations tend to have an international focus and position. For example, many SDP organizations have international workforces, particularly with regard to volunteers (which has been a topic of critical scholarship in the field) (van Luijk et al., 2019). Additionally, most SDP organizations are working to internationally set agendas (e.g. the UN’s SDGs), many organizations in our sample are working across multiple nations both in terms of their offices and programmes, and SDP organizations receive funding from geographically diverse funding organizations and bodies (Straume, 2019). The implication of this international context of SDP is likely that the influence of national politics and culture becomes somewhat diluted within SDP organizations compared to national sport organizations where nationalism still plays a particular role in the performance and traditions of national sporting teams. We argue, therefore, that this is a potential factor in fewer geographic variances in gender distribution across SDP organizations than has been seen within the national sport context.

Beyond the Numbers: Impact for Real World Practice

Critical mass theorists argue that numbers matter when considering organizational culture, dynamics, and performance (Dahlerup, 1988; Konrad et al., 2008). The overall gender balanced nature of SDP boards and leadership teams across our sample indicates that women impact and influence legislation, policy, and decision-making within SDP organizations due to them making up a considerable proportion of overall decision-makers (Dahlerup, 1988; Joecks et al., 2013; Konrad et al., 2008; Kramer et al., 2006). That said, our findings lack insight on which women (and other gender identities) are represented within SDP leadership and governance in terms of both their intersecting social identities and inclinations. This highlights the need for intersectional research to explore whether our findings reflect the representation of a diversity of women or just the most privileged. In doing so, it will be important to develop a multi-level understanding of inclusion within the leadership and governance of SDP organizations, including institutional structures and systems, organizational cultures, and individual empowerment. This is particularly important to explore within a sector that works to empower marginalized social groups.

In addition to a need for understanding which women have influence, there is also a need to understand the nature of their influence within their organizations. According to existing critical mass scholarship, the prevalence of a critical mass of women across the boards and leadership teams of most SDP organizations is likely (but not guaranteed) to result in cultures of collaborative discussion where women feel able to raise issues and difficult questions (Konrad et al., 2008). Considering our findings of overall gender balance across SDP organizations, this is positive and important for the empowerment of women leaders in the sector. An important question to further explore, however, is which issues and questions are being raised by these women and how this influences practice within the sector. For example, gender and politics scholars have critiqued the extent to which a substantive representation of women legislators benefits women as a group (Childs, 2004; Sawer et al., 2006). This is because critical mass theory “does not speak to the question of whether or not female legislators will seek to ‘act for’ women” (Childs & Krook, 2008, p. 728). Therefore, we believe that it is important and interesting for future research to explore whether a critical mass of women on the leadership and governance teams of SDP organizations actually results in the advancement of sport for gender equity: one of the core aims of the sector (Petry & Kroner, 2019).

In relation to this core sectoral aim of sport for gender equity, many SDP organizations work with vulnerable and marginalized girls and women on female-specific topics, such as female empowerment, gender-based violence, forced marriage, reproductive or sexual health, and female genital mutilation. Whilst previous research in sport has warned against the ghettoising of so-called ‘women’s issues’ to only female decision-making (Piggott & Matthews, 2021), within the SDP sector there is a duty of care and safeguarding is of the upmost importance. Additionally, some programme topics are so sensitive that female-only spaces are the only way to create safe spaces. Therefore, it is vitally important for SDP organizations to have collaborative environments where women leaders feel safe and able to raise sensitive topics and issues that impact women and girls in local communities, as well as influence over the design and development of related programmes. Our findings indicate that gender ratios across our organizational sample are conducive to such collaborative and inclusive cultures, but more exploration is required to understand if this is a reality within the sector.

Diverse perspectives within the boardroom have also been found to result in enhanced performance and innovation (e.g. Joecks et al., 2013). Again, there is a particular need for SDP organizations to be high-performing and highly innovative to respond to the dynamic nature of the real-world issues and challenges that they are working with. For example, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit in the spring of 2020, SDP organizations had to demonstrate considerable agility in their decision-making to meet the rapidly changing needs of the individuals and communities that they serve (Dixon et al., 2020). Whilst some challenges were similar to those faced by sport organizations during the pandemic, such as facility closures and activity/event cancellations, some SDP organizations took on additional responsibilities such as educational advancement and the provision of essential supplies (Dixon et al., 2020). Whilst critical mass theory indicates that the mostly gender balanced nature of SDP leadership and governance teams will have a positive impact on the performance and innovation of SDP organizations, the prevalence and impact of wider diversity needs to be further explored. This is because ‘diverse perspectives’ encompass more than solely gender parity, and so a greater understanding is required on the extent to which individuals from diverse social backgrounds have an equal opportunity to impact and influence policy and decision-making within the SDP sector. This is particularly salient when SDP programmes and organizations are working with a wide range of diverse social groups and identities.

CONCLUSION

This paper is the first known study to present and discuss data on gender distribution across the leadership and governance teams and positions of SDP organizations. This quantitative examination is instrumental to assess the current state of play, enable the opportunity for monitoring, and inform the design and development of future research. Overall, the boards and leadership teams of the 118 diverse SDP organizations that formed our sample were gender balanced, whilst the composition of chairs and most powerful leadership positions were gender tilted in favor of men. There were few notable geographic differences in gender distribution across continental groupings. Drawing on existing literature, we demonstrate how these findings contrast with recent reports of a continued underrepresentation of women across national and international sport organizations, as well as national/continental variations in gender distribution across organizations in the sport sector. We argue that such contrasting findings are related to organizational differences between the two sectors in: aims, values, and structures; opportunities to accumulate prestige and economic and social benefit; and national and international political and cultural contexts. We suggest that these variances can have differing implications on the conduciveness of sport and SDP organizations to be gender balanced and inclusive.

Drawing on critical mass theory, overall our findings suggest that women occupy a considerable proportion of decision-makers within SDP organizations and so have the opportunity to impact and influence legislation, policy, and decision-making (Dahlerup, 1988). Furthermore, findings from existing critical mass theory scholarship suggest that the majority of SDP organizations in our sample that have a critical mass of women across their workforce, leadership teams, and boards are more likely to be high performing and innovative than those without a critical mass of women (Joecks et al., 2013). We argue that the presence of female voices and highly innovative working are particularly important for SDP organizations that often work with marginalized and vulnerable women on female-specific topics, as well as within dynamic environments that require agility in decision-making teams and structures.

Whilst the findings present an overall positive picture, there were significant variances in female representation across SDP boards and leadership teams. For example, some SDP organizations operated with uniform or skewed boards and leadership teams. This means that these organizations are characterized by homogeneity and majority/minority sub-groups that can be significant in shaping interaction and decision-making dynamics (Kanter, 1977). Furthermore, even within gender balanced teams, Kanter (1977) suggests that there is the potential for sub-groups to develop, which can impact the extent to which different individuals within the group have power or voice to influence decision-making. Therefore, to truly understand group dynamics across decision-making teams of SDP organizations, we call for qualitative research to explore where decision-making power is actually located within dynamic SDP organizations, the extent to which women and other historically marginalized groups have power to influence decision-making, and the nature of the influence of these individuals. This is important to distinguish between women having a seat at the table and having a voice to make change. If qualitative research provides further evidence that the SDP sector is a mostly gender inclusive sector, this could importantly provide insight on good practice and key learnings to inform the practice of organizations within less inclusive sectors, such as the sport sector.

Notes

1 The MDGs have since been replaced by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

2 After sharing a draft of the survey with contacts working in SDP organizations, it was agreed that ‘board’ was a commonly used and understood term within the SDP field, whilst ‘leadership team’ was less clear. Therefore, within the survey, respondents were asked to report information on leadership/management/executive teams to account for different terminology used across different organizations. For the purpose of this article, we encompass all of these teams under the term ‘leadership teams’.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to sportanddev for their support throughout the research design and data collection processes. A particular note of gratitude goes to Paul Hunt for his generous contribution of time, knowledge, and experience to the project. We also want to recognise Mariann Bardocz-Bencsik’s work in developing the sportanddev database that was so helpful in distributing our survey. Thanks also to Beyond Sport and the Sport for Development Coalition for helping us to distribute our survey. Finally, we would like to thank our colleagues who reviewed early drafts of the survey, and of course our informants who took the time to participate in the research.

REFERENCES

Adriaanse, J. (2016). Gender diversity in the governance of sport associations: The Sydney Scoreboard Global Index of Participation. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 149-160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2550-3

Burton, L. (2015). Underrepresentation of women in sport leadership: A review of research. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 155-165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.02.004

Caudwell, J. (2007). On shifting sands: The complexities of women’s and girls’ involvement in Football for Peace. In J. Sugden & J. Wallis (Eds.), Football for Peace: The Challenges of Using Sport for Co-existence in Israel (pp. 97-112). Meyer and Meyer Sport.

Chawansky, M. (2011). New social movements, old gender games?: Locating girls in the sport for development and peace movement. In A. C. Snyder & S. P. Stobbe (Eds.), Critical Aspects of Gender in Conflict Resolution, Peace building, and Social Movements (Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change) (Vol. 32, pp. 121-134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Childs, S. (2004). New Labour’s Women MPs: Women Representing Women. Routledge.

Childs, S., & Krook, M. L. (2008). Critical mass theory and women’s political representation. Political Studies, 56(3), 725-736. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00712.x

Claringbould, I., & Knoppers, A. (2008). Doing and undoing gender in sport governance. Sex Roles, 58(1-2), 81-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9351-9

Clutterbuck, R., & Doherty, A. (2019). Organizational capacity for domestic sport for development. Journal of Sport for Development, 7(12), 16-32. https://jsfd.org/2019/03/01/organizational-capacity-for-domestic-sport-for-development/

Collison, H., Darnell, S., Giulianotti, R., & Howe, D. (2019). Introduction. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 1-10). Routledge.

Dahlerup, D. (1988). From a small to a large minority: Women in Scandinavian politics. Scandinavian Political Studies, 11(4), 275-298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.1988.tb00372.x

Darnell, S., Field, R., & Kidd, B. (2019). The History and Politics of Sport-For-Development: Activists, Ideologues and Reformers. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dixon, M., Hardie, A., Warner, S., Owiro, E., & Orek, D. (2020). Sport for development and COVID-19: Responding to change and participant needs. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.590151

Elling, A. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On reintegrating quantitative methods and gender research. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4-5), 430-436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214543124

Elling, A., Hovden, J., & Knoppers, A. (Eds.). (2019). Gender Diversity in European Sport Governance. Routledge.

Elling, A., Knoppers, A., & Hovden, J. (2019). Meta-analysis: Data and methodologies. In A. Elling, J. Hovden, & A. Knoppers (Eds.), Gender Diversity in European Sport Governance (pp. 179-191). Routledge.

Evans, A., & Pfister, G. (2021). Women in sports leadership: A systematic narrative review. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(3), 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220911842

Gal, A., & Foldesi, G. S. (2019). Hungary: Unquestioned male dominance in sport governance. In A. Elling, J. Hovden, & A. Knoppers (Eds.), Gender Diversity in European Sport Governance (pp. 70-80). Routledge.

Gaston, L., Blundell, M., & Fletcher, T. (2020). Gender diversity in sport leadership: An investigation of United States of America national governing bodies of sport. Managing Sport and Leisure, 25(6), 402-417. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1719189

Giulianotti, R., Hognestad, H., & Spaaij, R. (2016). Sport for development and peace: Power, politics, and patronage. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1(3/4), 129-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2016.1231926

Hayhurst, L. (2011). Corporatising sport, gender and development: Postcolonial IR feminisms, transnational private governance and global corporate social engagement. Third World Quarterly, 32(3), 531-549. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.573944

Hayhurst, L., Thorpe, H., & Chawansky, M. (2021). Sport, Gender and Development: Intersections, Innovations and Future Trajectories. Emerald Publishing.

Hayhurst, L., Wilson, B., & Frisby, W. (2011). Navigating neoliberal networks: Transnational internet platforms in sport for development and peace. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 46(3), 315-329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210380575

Herasimovich, V., & Alzua-Sozabal, A. (2021). Communication network analysis to advance mapping ‘sport for development and peace’ complexity: Cohesion and leadership. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 56(2), 170-193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690220909748

Hovden, J. (2010). Female top leaders–prisoners of gender? The gendering of leadership discourses in Norwegian sports organizations. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 2(2), 189-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2010.488065

Hoye, R., & Cuskelly, G. (2007). Sport Governance. Routledge.

International Olympic Committee. (2018). IOC gender equality report. https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/News/2018/03/IOC-Gender-Equality-Report-March-2018.pdf

International Paralympic Committee. (2017). IPC diversity and inclusion policy. https://www.paralympic.org/sites/default/files/document/170313091602678_2017_January_IPC+Diversity+and+Inclusion+Policy_FINAL.pdf

Joecks, J., Pull, K., & Vetter, K. (2013). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm performance: What exactly constitutes a ‘critical mass’? Journal of Business Ethics, 118(1), 61-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1553-6

Jones, G., Wegner, C., Bunds, K., Edwards, M., & Bocarro, J. (2018). Examining the environmental characteristics of shared leadership in a sport-for-development organization. Journal of Sport Management, 32(2), 82-95. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0274

Kang, S., & Svensson, P. (2019). Shared leadership in sport for development and peace: A conceptual framework of antecedents and outcomes. Sport Management Review, 22(4), 464-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.010

Kanter, R. (1977). Some effects of proportions in group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965-990. https://doi.org/10.1086/226425

Kanter, R. (1987). Men and women of the corporation revisited. Management Review, 76(3), 14-16.

Kay, T., & Spaaij, R. (2012). The mediating effects of family on sport in international development contexts. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(1), 77-94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210389250

Kidd, B. (2008). A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society, 11(4), 370-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430802019268

Knoppers, A., Spaaij, R., & Claringbould, I. (2021). Discursive resistance to gender diversity in sport governance: Sport as a unique field? International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2021.1915848

Konrad, A. M., Kramer, V., & Erkut, S. (2008). Critical mass: The impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organizational Dynamics, 37(2), 145-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2008.02.005

Kooiman, J. (Ed.). (1993). Modern governance: New government-society interactions. Sage.

Kramer, V., Konrad, A., & Hooper, M. (2006). Critical mass on corporate boards: Why three or more women enhance governance. Wellesley Centers for Women.

Lindsey, I. (2017). Governance in sport-for-development: Problems and possibilities of (not) learning from international development. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(7), 801-818. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215623460

Lyras, A., & Welty Peachey, J. (2011). Integrating sport-for-development theory and praxis. Sport Management Review, 14(4), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.05.006

MacIntosh, E., & Spence, K. (2012). An exploration of stakeholder values: In search of common ground within an international sport and development initiative. Sport Management Review, 15(4), 404-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.03.002

Matthews, J. J. K., & Piggott, L. V. (2021). Is gender on the international agenda? Female representation and policy in international sport governance. UK Sport. https://www.uksport.gov.uk/-/media/files/international-relations/research-final-report.ashx

Meier, M., & Saavedra, M. (2009). Esther Phiri and the Moutawakel Effect in Zambia: An analysis of the use of female role models in sport-for-development. Sport in Society, 12(9), 1158–1176. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430903137829

Oxford, S., & McLachlan, F. (2017). You have to play like a man, but still be a woman: Young female Colombians negotiating gender through participation in a sport for development organization. Sociology of Sport Journal, 35(3), 258-267. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2017-0088

Pape, M. (2020). Gender segregation and trajectories of organisational change: The underrepresentation of women in sports leadership. Gender & Society, 34(1), 81-105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243219867914

Petry, K., & Kroner, F. (2019). SDP and gender. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 255-264). Routledge.

Piggott, L., & Matthews, J. (2021). Gender, leadership, and governance in English national governing bodies of sport: Formal structures, rules, and processes. Journal of Sport Management, 35(4), 338-351. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2020-0173

Ponic, P., Reid, C., & Frisby, W. (2010). Cultivating the power of partnerships in feminist participatory action research in women’s health. Nursing Inquiry, 17(4), 324-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2010.00506.x

Sawer, M., Tremblay, M., & Trimble, L. (Eds.). (2006). Representing women in parliament: A comparative study. Routledge.

Schull, V., Shaw, S., & Kihl, L. A. (2013). If a woman came in… she would have been eaten up alive: Analyzing gendered political processes in the search for an Athletic Director. Gender & Society, 27(1), 56-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243212466289

Sport England, & UK Sport. (2016). A code for Sports Governance. https://www.sportengland.org/campaigns-and-our-work/code-sports-governance#:~:text=A%20Code%20for%20Sports%20Governance%20sets%20out%20the%20levels%20of,government%20and%20National%20Lottery%20funding

Straume, S. (2019). SDP structures, policies and funding streams. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 46-58). Routledge.

Svensson, P. (2017). Organizational hybridity: A conceptualization of how sport for development and peace organizations respond to divergent institutional demands. Sport Management Review, 20(5), 443-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.03.004

Svensson, P., & Hambrick, M. (2016). “Pick and choose our battles”: Understanding organizational capacity in a sport for development and peace organization. Sport Management Review, 19(2), 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.02.003

Svensson, P., Hancock, M., & Hums, M. (2017). Elements of capacity in youth development nonprofits: An exploratory study of urban sport for development and peace organizations. Voluntas, 28(5), 2053-2080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9876-7

Saavedra, M. (2009). Dilemmas and opportunities in gender and sport-in-development. In R. Levermore & A. Beacom (Eds.), Sport and International Development (pp. 124-155). Palgrave Macmillan.

The International Platform on Sport and Development. (2021). What do we mean by ‘development’? Retrieved September 3, 2021 from https://www.sportanddev.org/en/learn-more/what-sport-and-development/what-do-we-mean-development

The International Platform on Sport and Development. (2023). What we do. Retrieved April 28, 2023 from https://www.sportanddev.org/about-us/what-we-do

Thorpe, H., & Chawansky, M. (2017). The gendered experiences of women staff and volunteers in sport for development organizations: The case of transmigrant workers of Skateistan. Journal of Sport Management, 31(6), 546-561. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0147

Torchia, M., Calabro, A., & Huse, M. (2011). Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 299-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0815-z

UN Women. (2020). Sport for Generation Equality: advancing gender equality in and through sport https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/3/news-sport-for-generation-equality

van Luijk, N., Forde, S., & Yoon, L. (2019). SDP and volunteering. In H. Collison, S. Darnell, R. Giulianotti, & D. Howe (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Sport for Development and Peace (pp. 285-295). Routledge.

Velija, P. (2022). A sociological analysis of the gender pay gap data in UK sport organisations. In P. Velija & L. Piggott (Eds.), Gender Equity in UK Sport Leadership and Governance (pp. 197-216). Emerald Publishing.

Welty Peachey, J., & Burton, L. (2017). Servant leadership in sport for development and peace: A way forward. Quest, 69(1), 125-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1165123

Western, S. (2008). Leadership: A Critical Text. SAGE Publications.

Women Win. (2022). GRLS. Retrieved 13 Sepember, 2022 from https://www.womenwin.org/grls/