Graham Hingangaroa Smith1 and Linda Tuhiwai Smith2

1 Massey University, New Zealand

2 Te Whare Wananga o Awanuiarangi, New Zealand

Citation:

Smith, G.H. & Smith, L.T. (2023). Foreword: Indigenous Sport and Development – Decolonising Sport in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

FOREWORD: INDIGENOUS SPORT AND DEVELOPMENT – DECOLONISING SPORT IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

This foreword brings together the theoretical analyses of Kaupapa Māori (Smith, 1997) and Decolonising Methodologies (Smith, 2021) alongside an extensive practice-based knowledge of Indigenous sport and Indigenous development in Māori contexts in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). We critically examine changing contexts and understandings of both sport and development and how those concepts have been applied to and for Māori in Aotearoa NZ. We argue that many of the taken for granted ideas about sport and development need decolonising, disrupting, and reframing within an Indigenous frame we refer to as Kaupapa Māori. This is necessary if we are to fully appreciate and understand how sport and development might work relationally for the well-being of any Indigenous communities and collectives. We explore the role and relationship between sport and development through four political contexts: (a) a historic context and the role of sport as an organized physical activity in an Indigenous society that held its own sovereignty, (b) an Imperial and colonial context in which sport as conceived and introduced by British colonisation was wielded as an instrument of colonisation, (c) a neo-liberal context in which sport as an activity of market forces, competition and privatisation reshaped the organisation of sport and development as a form of economic neoliberalism, and (d) a decolonising and Kaupapa Māori context in which sport has been reimagined and reframed in terms of Indigenous Māori development. The first two political contexts will be covered less extensively because more is known of these two periods, however, there are threads of important ideas that we wish to draw upon that inform Māori concepts of sports and development in the current context.

In keeping with the theme of this Special Issue on indigenous sport for development, this foreword is written from an Aotearoa NZ, Indigenous perspective. While this paper primarily documents the emergence of Indigenous development ‘in’ and ‘through’ sport in Aotearoa NZ, we think its relevance extends to other Indigenous contexts where Indigenous peoples live in the legacy of colonial contexts of dominant and subordinated power expressed and experienced through political, social, economic, cultural, and racial structures. Sport is only one of several social systems through which Indigenous communities have experienced, resisted, and sought to transform colonial relations of power. In the paper, we refer to the term “Māori” as a collective term for an Indigenous Peoples who mostly define ourselves through our own pēpeha (tribal sayings) as belonging to specific geographies marked by our mountains and waterways, to ancestors, and to collective iwi or “tribal” communities. We also acknowledge the co-development of Pacific peoples who have migrated from a range of Pacific Island countries and who now reside within Aotearoa and who also contribute significantly within most sports in NZ. Māori people represent approximately 892,200 or 17.24% of the 5.127 million people in NZ and Pacific people number 381,640 or 8.1% of the NZ population (Statistics NZ, 2022). Both groups have a young demographic with most Māori and Pacific people being under the age of twenty-five years. This youthful population is where the Indigenous engagement in sport and development is primarily being expressed.

While the current growth of access, participation, and success of Indigenous Peoples into sports is an emerging phenomenon – that has not always been the case. In fact, for Māori, we suggest this growth correlates in interesting ways with two significant movements; firstly, the Māori language and schooling movement that occurred from the early 1980s and, secondly, the neo-liberal economic reform movement that began in the late 1980s and took hold during the 1990s. The sequence and converging of these two movements is important, we argue, because the Māori language and cultural revitalisation movement revolutionized Māori identity and sense of agency and established a momentum that helped Māori engage to a greater extent than otherwise with the sweep of neo-liberal reforms that took effect in the 1990s.

DECOLONISING AND KAUPAPA MĀORI THEORY AND METHODOLOGIES

In approaching this foreword as a collaborative piece of writing, we have drawn on our own theoretical strengths and positionality in Kaupapa Māori and Decolonising Methodologies, and our deep practice knowledge in education and sport for development. Our practice-based knowledge comes from the different roles we have played as educators, coaches, managers, and in governance. Graham Smith was raised in sports, from boxing to athletics and cricket and has been a player, coach, and administrator in rugby in Auckland. He attended St. Stephen’s Māori Boarding School which at the time was renowned for its sporting accomplishments. He was the first Māori Club Captain of the University of Auckland Rugby Club, a member of the national NZ Māori Rugby Board, and was on the committee that organized the inaugural Māori sports awards. Linda Smith spent many years trying to avoid sport, which was mostly an impossibility in the NZ school system as physical education (PE) and sports were compulsory. Her parents paid good money for tennis coaching lessons, she did well in athletics and netball, and nearly drowned in swimming. It all caught up with her when she became head of PE and sport at a large intermediate school in Auckland and ended up organizing and coaching netball and soccer teams, overseeing weigh-ins for rugby and rugby league teams, umpiring softball and senior netball games, hosting regional athletic event, and ensuring all students could swim and pass their life saving certificates. Our research spans the role of colonisation in schools, the Native Schools System, the impact of Neo-liberalism, Kaupapa Māori, and Decolonising Methodologies.

We have brought together two theoretical lenses that complement our analysis of Indigenous sport and development. A decolonising approach understands the role and impact of imperialism and colonialism on the world as we know it, in a historical, material, and epistemic sense, and further holds to a set of ideas about ways to critique systems and institutions of power. A decolonising approach also offers ways to think about knowledge and the making of knowledge outside the dominant framing of knowledge and research. Reframing, writing, theory making, and storytelling are just some of the methodologies that decolonising scholars draw upon in their work. One aspect of reframing is to ensure that our research is not focused on ‘damage-centered research’ (Tuck, 2009) or victim blaming, but focuses instead on knowledge questions that position the colonized, in this case Māori people, as epistemic equals with valid and legitimate questions and solutions that are grounded in their own knowledge systems.

Our Kaupapa Māori approaches to theory and praxis have emerged from a critical understanding of several transformative Māori initiatives that began in the 1980s, as Māori specific theories and methods for generating knowledge, governing research, and working for Māori development were established. These understandings have informed approaches to theory and research that go well beyond methods to addressing systemic attitudes and norms about research, research ethics, and the institution of research itself in the western academy. Kaupapa Māori is much more than Māori leading and carrying out research, but being able to center Māori theorising Māori experiences by drawing insights from Māori knowledge and practices and committing to an agenda of transformative outcomes. We will address some of these understandings more fully later in this foreword as the influence of these insights has spread across Māori society including sport.

THE HISTORIC PRE-COLONIAL CONTEXT: WHEN MĀORI HELD MANA MOTUHAKE MĀORI PLAYED SPORT

In both historical and contemporary contexts, the term sport is so deeply associated with European and British imperialism that it can be difficult to imagine the existence of sport in Māori or Indigenous contexts prior to the arrival of Europeans. Yet, we know from other examples such as surfing in Hawaii or the earlier version of Lacrosse in North America that Indigenous peoples invented and played sport. These were often looked down upon or ridiculed by Europeans as mere ‘games’ that children played, a standard classic ploy of colonisation and racism to diminish native peoples.

When Māori exercised full mana motuhake (autonomy) over their lives, Māori people played sports. Māori were physically active. Māori were competitive. Māori enjoyed physical and artistic achievements. Māori had fun. Māori had ideas about the physical body and how it could be trained and prepared. Māori played sport in groups and as individuals. Māori people designed and used equipment for sport. Kite flying, waka races, string games, stick games, poi, running, swimming, climbing, martial arts and weaponry training (Brown, 2008). There were indoor and outdoor sports, daytime, and night-time sports. The environment of Aotearoa was conducive to physical activity and the genealogies of Māori are written into their DNA as are the stories of an ocean crossing people who were strong, adventurous, purposeful, and healthy. Many of our sports could be played by the whole community regardless of age, ability, or gender while others were created specifically to train and prepare people for fishing, hunting,, warfare, carving, or for weaving.

The story of Māori and sport is, however, not just about the activities of sport. It is primarily about a unique world view, a knowledge system or mātauranga and the application of knowledge to practice which we call tikanga that defines how sport was understood. The ‘playing fields’ of mana Motuhake, unlike the playing fields of the British empire, were written into our cosmology, the earth mother and sky father’s embrace of their children from which our concept of whanau or extended family is derived, in the stories of the stars, in the seas, ocean currents and crashing waves, in the rivers and lakes, mountain ranges and plains, forests and villages. Our stories tell of extraordinary physical feats of gods and demi-gods, ancestors, and their human descendants. Sport was sourced in the Atua or “Gods” both male and female and was brought to human beings as knowledge and gifts to help human beings live. Hineraukatauri and Hineraukatamea, for example, were atua sisters. One was the atua of flute music and the other was the atua of music and games. Rongomaraeroa, was an atua of peace within whose realm sports and music were protected. In this sense, sports were an expression of peace (Reed, 1999).

The knowledge of sport and music were part of a knowledge system that was conceptualized and practiced in Wharekura or Schools, such as the Whare Wānanga, the School of Higher Learning, the Whare Pora or School of Weaving, and the Whare Tapere or the School of Sports, Entertainment and Performing Arts. Each of these schools were schools of learning and practice as well as schools that strived for excellence. Each had their own tikanga or protocols. Sports and arts were often grouped together and existed as neutral places of enjoyment. One story tells of the School of Huiterangiora which tells of a man from the underworld called Miru who fell in love with a human, Hinerangi. Miru lived in the human world for some time and then returned to the underworld with some of his family where he taught them the knowledge of sports and arts that they were able to pass on when they returned to the world of light where humans dwelled (Calman, 2015a; 2015b; Reed, 1999).

The conceptual ways that Māori understood and played sport were embedded in the collective way of living as inter-generational and relational groups. One key value that governed most ideas about social life was mana. It can be argued that the role of the individual and the collective was driven by the pursuit of mana (Parsonson et al., 1981). Individual excellence enhanced collective mana. Collective mana gave an individual the mana to behave well and strive to be better. Conversely, individual failure in high stakes contexts diminished the mana of the collective. Being regarded by others as having mana and being respected for mana is an important ethical practice. In this worldview, sport was not associated so much with personal development or societal development but with ideas about community, joy and pleasure and the idea of being a self-determining people. When Māori had mana motuhake, Māori had the freedom to lead lives enriched by sport and recreation that had been gifted by the Atua for collective well-being. The spiritual and ancestral connection to atua, the importance of whānau, the drive to excel, the expression of joy, and the pursuit of mana are important tenets of Māori sports.

THE IMPERIAL AND COLONIAL CONTEXT: WHEN SPORT WAS USED TO COLONIZE AND CONTROL MĀORI

Māori land, resources, knowledge, language, and culture came under intense scrutiny and attack once British settlers arrived in Aotearoa in increasing numbers following the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840, and particularly after the NZ colonial Government was formally established in 1852. It may seem unnecessary to repeat the story of British colonisation of Aotearoa, but the impact of colonisation was devastating for Māori. Like other Indigenous Peoples, the impacts of colonialism and colonisation were severe and left Indigenous Peoples struggling to survive for generations with a continuing legacy of social, environmental and economic deprivation, and disproportionately high rates of poor health, incarceration, poverty, and homelessness. Every aspect of their lives was upended and most of their resources were systematically taken and or destroyed and replaced with a vastly different world view, identity and knowledge system through colonial institutions and value systems. Sport was one of the many social mechanisms by which colonialism asserted a different hegemony of what was normal and acceptable in a colonial society.

As others have argued, sport was a way to civilize the natives, to embed concepts of white racial superiority and to orient allegiance both politically and culturally to Britain (Mangan, 2003; Roser, 2016). British ideas of sport deeply entrenched categories of race, class, ability, and gender. These categories were embedded in the school system (McCulloch, 1990, 2011) and in the way settler communities organized themselves including claiming and often taking more native lands and resources for their sporting activities such as racecourses, golf courses, recreational fishing waterways, and hunting activities. The British introduced animals for hunting purposes that threatened NZ’s native wildlife. Sporting clubs, like scientific societies, sprung up as settlers gained control and wealth. Sport fully expressed colonial ideas about race and the racial superiority of white settler males. Sport was to be reified as being for “God, King, and Country!” and was to be seen as a ‘gift’ from Britain to the colonies. Colonial sport idealized ‘muscular Christianity’, the white male body, and infused it with the character of a civilized man. For example, the courageous, idealized ‘heroic’ sportsman, who above all obeyed the rules, respected the captain, was a good character, and believed in fair play. Like colonial life in general, the colonial sportsman also made the rules, governed the rules, and refereed the rules. This was the case in Aotearoa NZ throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and only ceasing in recent years.

Māori people did engage in and subvert or indigenize these new colonial sports which were often introduced through the native schooling system and Māori Boarding schools. In many areas Māori had great natural talent and enthusiasm. Even when excluded from participation in some places, Māori established their own clubs including racing clubs and racecourses. Sports were played competitively amongst the different Marae or whanau-based communities. Sports such as rugby, tennis, hockey, and netball took hold in some Māori communities as their sport, which they completely controlled in terms of organising and staging tournaments. To this day, many Marae host sports teams and enhance their mana through their generous hospitality. Sport is still seen as a whanau activity. In the early part of the 20th Century, Māori played sports such as rugby, polo, cricket, hockey, golf, and tennis. The first rugby tour of the UK by a national rugby team was in 1888-1889 with an all-Māori team called the NZ Natives and led by Joe Warbrick. In the 1880s there were several Māori rugby clubs. Māori women have also been ground breakers in sport. In 1957 the first NZ woman to play at Wimbledon was a Māori woman Ruia Morrison who has only recently been given a NZ honour in recognition of her achievements in tennis.

Māori were stereotyped as being ‘naturally’ good at team sports, but not disciplined enough to be successful in individual sports. They were frequently overlooked as suitable candidates for leadership positions, such as team Captain or as coaches, managers, or administrators. While they were often talented, creative and innovative, Māori were viewed through the lens of race as being undisciplined, savage, unruly and un-sportsman like (Hokowhitu, 2004). Even their humour and expressions of joy were often negatively perceived and regarded as symptomatic of ill-discipline.

What were classified as ‘traditional’ Māori games continued to be played but the opportunities for Māori to play sports in the full context of communal life had been diminished as Māori had become dispersed and living away from their traditional homelands. Traditional Māori sports were often diminished in status and were portrayed simplistically as children’s games and or entertainment rather than real sports. Some of these games, such as string games and stick games, were introduced into the schooling curriculum of the Native or Māori schools in the 1930s and continue to be taught to this day. The haka ritual was inaccurately viewed as entertainment (Hapeta et al., 2018) and other Māori martial arts were mostly suppressed until the late twentieth century (Jackson & Hokowhitu, 2002).

Education as a tool of colonization went hand in hand with sport and goes some way to explain why Māori were both colonized by sport and in sport (Simon & Smith, 2001). The school curriculum for Māori schools including the secondary boarding schools from the early to mid-twentieth century emphasized manual subjects, which created and perpetuated myths that Māori were not capable of learning academic subjects. Students were corralled into believing they were only good enough for manual and physical labour. Sport became an area that Māori, especially boys, believed they had a chance to excel.

The sports introduced through colonialism was a form of ‘trojan horse’ that sought to assimilate Māori by both covertly and overtly undermining Māori cultural ideas and values and replacing them with mono-cultural, ‘rule bound’ sport institutions and facilities at the local and national levels. Unlike the government-controlled institutions of law, education and public health, sports were organized and overseen by Pakeha civil settler society who also had power and control of sport and development across NZ. Local sports clubs like local governments were dominated significantly by Pakeha or non-Māori people. Players were socialized into sports at schools with top schools producing elite players. There was a ‘class hierarchy’ related to schools attracting and capturing talented sportspeople, firstly to enhance their own sports programs and secondly, contribute to the production of elite sportspeople into selected sports. These activities have often been aimed at talented Māori and Pacific youth.

The deep social inequities and racism experienced in quite different ways by Māori and by Pacific peoples (who had migrated to NZ mostly from the early 1960s) boiled over in the 1970s into direct political protests. Pacific peoples had been brought to NZ as migrants to help service the manufacturing industry and urban centres. Māori had moved to urban areas in search of work having been pushed out of their lands and rural communities by Government policies. One of the focal points of political resistance was in relation to rugby and the NZ Rugby Union continuing to play against the apartheid regime’s Springboks. The South African Springbok Tour of 1981 brought to a head, among other political issues, the challenges facing colonial ideas about sport and the way sport was organized in NZ. Māori communities and families were divided by the protest action that was used to bring the tour to a halt. However, the protest revealed the deep association and commitment to racism and colonialism that was ingrained, at that time, in the national sport of rugby and the national psyche of many New Zealanders.

The period of colonialism and colonization that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries was a period of great turmoil, loss, and struggle for survival for Māori. Sport offered one of the few opportunities for Māori to excel at what they were good at but even then, their efforts and opportunities were constrained by colonial attitudes and values in relation to sport. Māori were able to engage and resist, often organising their own sports around their own ideas and values. In this period there was extreme underdevelopment of Māori communities and institutions, perhaps more accurately described as deliberate deprivation. Following this period of underdevelopment came a phase focusing on development as assimilation, as coercing and persuading Māori to forgo their cultural ways and adapt to the dominant colonial system. Māori resisted assimilation – Māori still wanted and needed to be Māori. Māori resistance has redefined the notion of development – it has now become a term that is related to cultural, social, and political ideas about Māori self-development, as mana Motuhake or development as more self-determining. The mid-1980s are significant in relation to Māori development as beginning a period of cultural, social and economic revitalisation and fight back. Sport played a role in focussing Māori on addressing systemic institutional barriers to Māori participation and pursuit of well-being.

THE NEOLIBERAL TURN: MĀORI AND THE SPORTS MARKET—DEVELOPING INDIVIDUAL AGENCY VS. THE CULTURALLY CONNECTED SPORTSPERSON

The 1980s in NZ also saw the rise of neoliberal, free market economics and the overthrow of the country’s long association with the Welfare State (Kelsey, 1993). This did not mean the end of colonialism but rather signalled a turn of colonialism towards a specific version of liberal economics and a change in the form of colonisation. Until this time, NZ had been highly regarded internationally as being a model of Welfare State provision. In 1984, the Fourth Labour Government led by David Lange came to power and his Minister of Finance at that time, Roger Douglas introduced radical economic reforms drawing on the lessons of Ronald Reagan (influenced by the Chicago School of Economics), and Margaret Thatcher who had initiated similar reforms in Britain. The underpinning thinking here was that increased economic freedom would stimulate increased economic development and social prosperity for individuals.

There were four key themes (Jesson, 1987) in the neoliberal economic agenda:

- A move away from State ownership of public assets and services to privatisation.

- A move to stimulate economic growth by deregulating the corporate sector and by lowering corporate taxes and union influence on wages.

- A move to cut public spending and to assert a ‘user pays’ system.

- A move to reinstate an accent on nuclear colonial family values, the primacy of the possessive individual, and moral authoritarianism.

In other words, the neoliberal ideology supported free enterprise, competition, deregulation, and an emphasis on individual responsibilities, rights, choices and freedoms. The ideal neoliberal individual (cf. Hayek, 1974) was someone who was self-interested and competitive, motivated to better themselves and rise above others, was a free agent willing to submit to market forces, and sought to accumulate wealth. One important metaphor of neo-liberalism, especially in regard to equity and the issues facing Māori and other poor and disadvantaged communities, was the sporting metaphor of the ‘level playing field’. This implied that everyone should be considered equal with equal opportunities to succeed. Despite this myth, the reality has been that the ‘field’ was in fact uneven and therefore created outcomes of winners and losers. Neoliberalism gave a ‘head-start’ advantage to the winners and enhanced their opportunities to maximize their gains. The losers were considered to have been the creators of their own misfortune because they made poor choices, did not try hard enough, did not achieve required standards, and were therefore responsible for causing their own social and economic disadvantage. There was no real appreciation in this ideology for community or culture. In this sense, neoliberal ideology does not care whether communities or cultures thrive or not, because neoliberalism is focused on outcomes of individual meritocracy.

The impact of neo-liberal politics for Māori communities was initially devastating with state-owned industries being privatized and Māori finding themselves unemployed and ill-prepared to become their own business contractors/ managers (Kelsey, 1995). At one point in the early 1990s, one-quarter of Māori men were unemployed and, furthermore, blamed for their own unemployment. Neoliberalism created several points of tension for Māori and for other groups of New Zealanders by exacerbating their socio-economic and cultural underdevelopment. Those sport codes which had previously been amateur codes became more professionalized as individuals competed to position themselves in the ‘marketplace’ of sport. There was money to be made in sport. For Māori people, sport provided some talented individuals with the means to develop upward social and economic mobility by being recruited into professional sports both within NZ and abroad. These opportunities presented disadvantaged families with hope that their young people would gain status, employment, wealth, and realize the neo-liberal dream.

The neo-liberal notion of development in relation to sport was primarily the advancement of the self-interested individual rather than the development of community or culture. As the economic and social reforms were implemented, it has become more obvious as the years have progressed that neo-liberal policies in NZ made previous inequalities between Pakeha and Māori even worse despite the efforts of later governments to address some aspects of disadvantage. The safety net of the social welfare system failed many people and helped create an underclass or precariat of marginalized and vulnerable people of which a high proportion were Māori.

Māori development, however, has been carved out of a different set of aspirations and ideas. In some ways neo-liberalism presented opportunities that did not exist prior to the reforms. For example, previously ‘submerged’ systemic racism within colonial structures and practices were made more overt, and therefore obvious enough to be challenged and managed. Māori economic development was given greater priority than previously. Where neo-liberalism touted individual choice and opportunity, Māori interpreted these ideas as the choice to be Māori, the prospect to develop as Māori, and the opportunity to participate as Māori in all spheres – in the economy, business, education, health, and sport. ‘Choice theory’ was also a hegemony perpetuated by neoliberal interest groups who falsely sold the belief that everyone had equal choices – what they neglected to acknowledge was the fact that not everyone started from the same place – those who already had more wealth were able to exact more choices than those who were less wealthy.

As they had done from the beginning of colonization, Māori people both engaged with and yet resisted strategies that pushed them towards rejecting their cultural identity and values. Community and cultural identity were at the core of the strengths Māori sportspeople could draw upon and by which they were motivated to achieve. The pursuit of mana for the collective still operated as a cultural reward system. Individual sportspeople wore their identity with pride through their names, their connections to their whanau, sometimes on their skin as tattoos, on uniform insignia, and in the use of te reo (Māori language). Cultural connectivity worked both ways in terms of community embracing their teams, heroes and sheroes and sportspeople acknowledging their communities.

A DECOLONISING AND KAUPAPA MĀORI APPROACH TO SPORT AND DEVELOPMENT

As mentioned at the beginning of this foreword, Kaupapa Māori as a movement of transformation, rather than development, emerged early in the 1980s and prior to the economic reforms of neoliberalism. The movement was stimulated by earlier Māori resistance politics of the 1970s and calls for the honouring of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the teaching of Māori language. The Waitangi Tribunal was established in 1975 that began a process of addressing NZ’s failure to honour the Tiriti o Waitangi. The Te Māori Art Exhibition to the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1984 reframed perspectives about Māori as creators of art, not just of artifacts of material culture, and as a culture that had a relationship with its art and environment. The Te Māori exhibition also trained many Māori as Museum docents, so they were able to talk about their culture and their art pieces in more positive and critical ways than they had been used to doing (Mead, 1984).

The development of Kohanga Reo, the Māori language nests, in 1982–essentially a preschool full-day program that only used the medium of Māori language–sparked a grassroots movement as parents and communities immersed their children in the Māori language. Kohanga Reo was followed by a schooling initiative called Kura Kaupapa Māori, which aimed to continue the philosophy and practices that were successful in the Kohanga Reo. Both these initiatives challenged the status quo of the education system at the time and led to changes in the Education Amendment Act 1989 that recognized their existence (Smith, 1997).

The genuine belief that communities could start their own kohanga reo and develop children as fluent Māori language speakers was part of a wider cultural revolution that stimulated a reclaimation and celebration of Māori culture and identity as something positive and worthy of pride. Kaupapa Māori as an approach to development, as well as a theory and praxis of development, emerged partly from the grounded cultural practices that Māori were using across the spectrum of grassroots initiatives and partly from the insights gained from analysing and theorising why these various initiatives were so successful. During this period, a diverse array of Māori cultural practices were being reclaimed and revitalized across the arts, the performing arts, including some aspects of martial arts, Māori ocean going voyaging, and Māori economic activity and sports.

Kaupapa Māori ways of being and doing things “by Māori and for Māori” fostered self-belief and enthusiasm for going ahead and organising a diverse range of activities that were grounded in Māori values. Not only were Māori participating in the professional sport codes, but they were also creating new approaches to sport. The Haka tradition, for instance, and other cultural elements are now increasingly witnessed in Rugby and some other sports. New sports evolved out of traditional sports (as in Waka Ama emerging as an internationally competitive sport) and insisting on the inclusion of Tikanga Māori – Māori custom into NZ sports (as in the use of cultural elements in national teams such as NZ’s Olympic Team), and some of the professional sports (for example, the NZ Team contesting the America’s Cup and the New Zealand Warriors Rugby League Team (Hapeta, 2018; Hapeta et al., 2018; Hapeta et al., 2019; Palmer et al., 2022).

Waka Ama, a form of outrigger canoe racing, for example, was introduced by people like Matahi Whakataka-Brightwell in 1985 when he started a canoe club Mareikura in Gisborne and shared his learnings from his time in Tahiti. Waka ama has grown into a national and international Indigenous sport with huge participation across age-groups, and about 50:50 participation by men and women. Māori participation in Waka Ama far outstrips their participation in the more British colonial sport of rowing. Māori identity and culture are a natural and taken for granted aspect of the sport. The national sport organisation values manaakitanga (reciprocity), hauora (well-being), whanaungatanga/ (relationships), and Tū tangata (responsibility). One of the successes of Waka Ama is the involvement of Māori from smaller communities and regions outside the urban centres which have the populations to support most professional sports.

Ki-o-Rahi is another example of a more traditional ball sport that has been revitalized (Brown, 2008). It is based on the story of Rahitutakahina and its rules are based entirely on Māori principles. The ball is referred to as Ki and the game is played on a round pitch. Ki-o-Rahi was what Māori played before colonial ball sports were introduced and when the settlers arrived with these new sports. Ki-o-Rahi went into decline, but Māori readily adapted to the new introduced games such as Rugby. However, Ki-o-Rahi is now making a comeback. Its revitalization journey began during the first World War and has really picked up from the 1970s. It is now played in schools and has national tournaments. Like Waka Ama, this is a sport which is inclusive of gender and age.

Endurance-related sports, like marathon running and triathlons, have been adapted by Māori into a cultural format. An event called Iron Māori is a cultural form of Triathlon that attracts high participation by Māori of all ages and abilities. Its primary purpose is to promote Māori fitness, health, and well-being. Iron Māori began in 2009 in the Hawkes Bay with participants joining as whanau teams, involving people of all ages. Some participants do all the disciplines, while others may form teams or whanau groups who choose to do specific elements of the event. Hundreds of people from across the country prepare for the event and turn up with their supporters wearing matching gear to cheer on their friends and whanau. Elite endurance participants are also present, but the emphasis is on whanau and other holistic benefits of health and well-being.

The story of the Black Ferns, NZ’s national women’s rugby team, provides another example of how important cultural values were to a team of mostly Māori and Pacific Players. After a disastrous performance in 2021 and allegations of bullying, the NZ Rugby Union conducted an environmental and cultural review. Here is one statement from the Executive Summary (Muir et al., 2022, p.1) of that report:

The Black Ferns team has created a significant whakapapa and legacy in a relatively short period of time. Since the Women’s Rugby World Cup was officially sanctioned by NZRFU in 1991, the Black Ferns have won five of the seven Rugby World Cups. The wāhine who wear (and pass on) the Black Ferns jersey, together with those who contribute to the team’s performance and success off the field, have bestowed mana on women’s rugby in Aotearoa and have much to be proud of and to uphold. Whakapapa translates to layering one layer upon another. The responsibility to maintain and positively contribute to the Black Ferns whakapapa is clearly evident within all members of the current team.

Māori concepts are used throughout the report as ways to describe what the team means to the sport. The players are referred to as wāhine, or women. The concept of mana is defined as bestowing mana on women’s rugby in Aotearoa and Whakapapa is translated as legacy and conveyed as an inter-generational commitment. These elements indicate a broader and deeper commitment by players and managers to tikanga and Kaupapa Māori. Culture is seen in this report as a positive aspect of personal and team development, as well as a means for fostering wider community engagement. Wāhine players had to be treated with mana for the team to have mana and a team with mana is more likely to win than lose. This proved to be the case when the Black Ferns won the Women’s Rugby World Cup in 2022 played in front of a packed crowd in the iconic Eden Park in Auckland, NZ.

How does a decolonizing and Kaupapa Māori approach in sport relate to development? Making space for Māori to reclaim their culture and identity through sport as well as being able to create and revitalize ancient sports has unleashed the spirit of Rakautauri and other ancient ancestors/atua who gifted sports and arts for Māori to enjoy. A decolonized approach has enabled participation not just at the level of playing sport but within the system of sport, at governance, management, and coaching levels. Kaupapa Māori normalizes Māori culture and identity and draws on culture and identity as strengths. Cultural identity for Indigenous Peoples is often fraught with the divisive legacy of cultural assimilation and so not all Māori can be assumed to have fluency in Māori language or strong iwi/tribal connections. Sport plays a critical role in facilitating and enhancing identity and cultural development. Sport does not govern or determine what counts as Māori culture but it does provide spaces in which identities can be, and need to be, affirmed and nurtured.

SPORT AND DEVELOPMENT – HOW HAS IT WORKED FOR INDIGENOUS MĀORI?

We have argued that notions of both sport and development need to be interpreted and understood through a decolonising and transforming Kaupapa Māori lens (Smith, 2015; Stewart-Withers & Hapeta, 2021). Such a lens enables us to understand that prior to any European or British influence, Māori had their own world-views and knowledge systems in which sport existed as a natural element of culture. Mana Motuhake or Māori sovereignty meant Māori people had their own control. Colonialism brought with it different ideas about sport and development that attempted to infantilize Māori sports and destroy Māori knowledge, language, and culture. Colonization was the colonial form of development and it basically meant Māori cultural replacement and assimilation into a dominant settler culture. As Māori adapted, engaged, and resisted some of these assimilatory processes, Māori found ways to participate and often excelled in sport when they had the opportunities. Neoliberalism recast development as being shaped by market forces and the rise of professionalized sports, which enabled some Māori to participate at the highest levels. The issues are not about whether or not Māori people can play sport. They can. The issue is whether colonial constructions of sport fully accept Māori sportspeople as Māori to participate in the sports at all levels when they have for so long been marginalized by white power structures. Kaupapa Māori developments have unleashed a range of Māori approaches to sports, including reclaiming and redesigning ancient sports, as well as re-shaping sports introduced through colonialism. When Māori can fully express their culture and identity then they can more fully participate in and transform the role of sport and development. We argue this also applies to the way researchers engage with the field of sport for development, the questions and approaches they have, and the lens they use to understand Māori and Indigenous in sport. It is important from a Kaupapa Māori and decolonizing lens that Māori and Indigenous people are not the objects of research, but rather are able to set their own research agenda and develop research and scholarship that centers Māori knowledge and culture. This provides a challenge for our NZ context – but also by extension for Indigenous Sport for Development more generally.

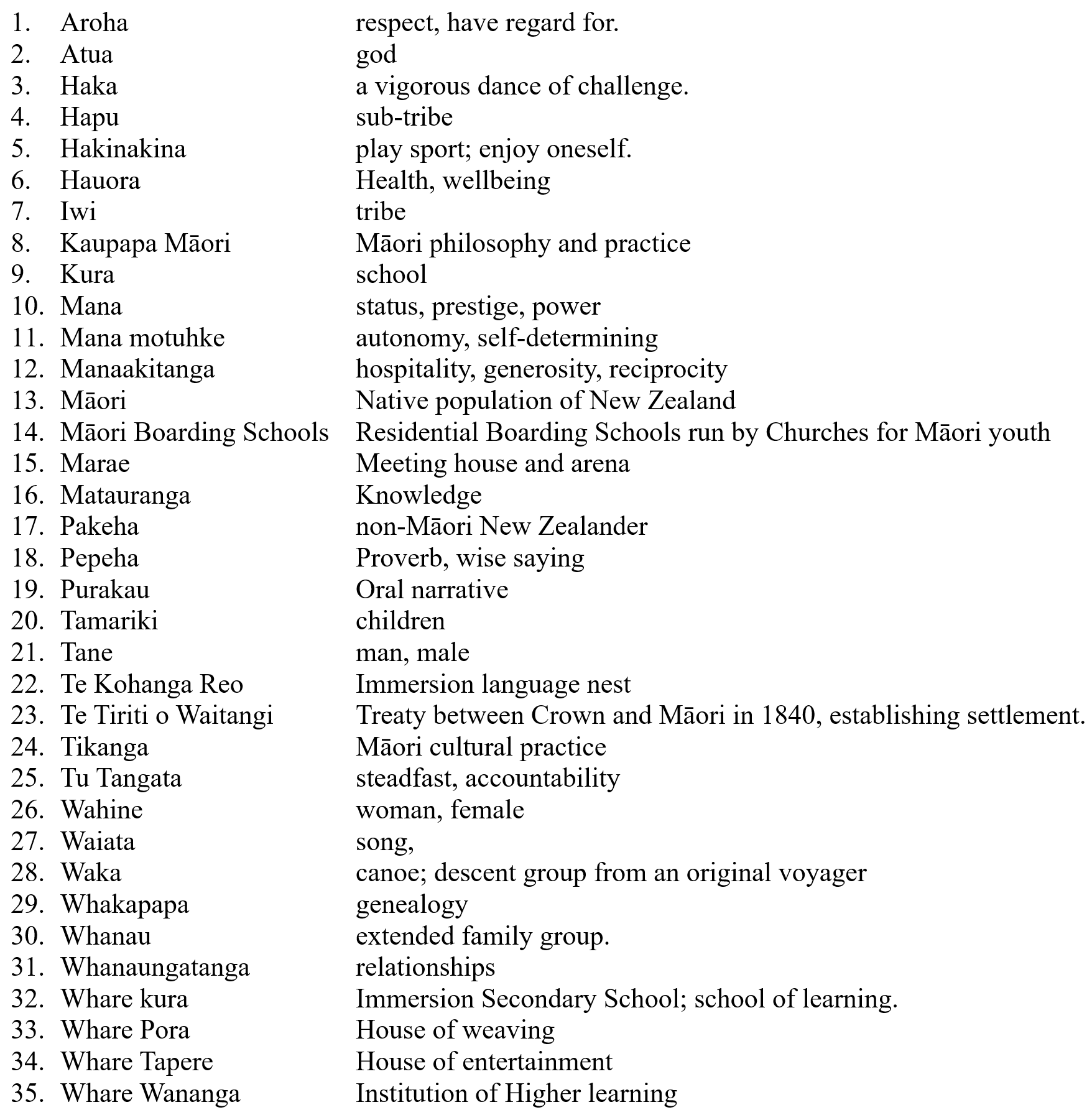

Table 1 – Glossary of Terms

REFERENCES

Brown, H. (2008). Ngā Taonga Tākaro Māori sports and games. North Shore NZ. Raupo.

Calman, R. (2015a) ‘Traditional Māori games – ngā tākaro – Sports and games in traditional Māori society’, Te Ara – the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, (accessed 10 April 2023) http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/traditional-Māori-games-nga-takaro/page-1

Calman, R. (2015b) Favorite Māori legends. Oratia Media.

Hapeta, J. (2018) An examination of cultural inclusion and Māori culture in New Zealand rugby: The impact on well-being. Unpublished PhD Thesis; Sport and Exercise Science; Massey University.

Hapeta, J., Stewart-Withers, R., & Palmer, F. (2019). Sport for social change with Aotearoa New Zealand youth: Navigating the theory-practice nexus through Indigenous principles. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 481-492. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0246

Hapeta, J., Palmer, F.R., & Kuroda, Y. (2018). Ka mate: A commodity to trade or taonga to treasure? MAI Journal, 7(2), 170-185.

Hayek, F.C. (1974). Individualism and Economic Order. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hokowhitu, B. (2004). Tackling Māori masculinity: a colonial genealogy of savagery and sport. The Contemporary Pacific, 16(2), 259-284.

Jackson, S.J. & Hokowhitu, B. (2002) Sport, tribes and technology: The New Zealand all blacks haka and the politics of identity. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 26(2), 125-139. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723502262002

Jesson, B. (1987) Behind the mirror glass: The growth of wealth and power in New Zealand in the 80’s. Auckland: Penguin.

Kelsey, J. (1993). Rolling back the state. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd.

Kelsey, J. (1995). The New Zealand experiment. Auckland University Press.

Mangan, J. A. (2003). The games ethic and imperialism: Aspects of the diffusion of an ideal. London.

McCulloch, G. (1990). Historical Perspectives on New Zealand Schooling. In A. Jones (Ed.), Myths and Realities (pp. 21-53). Dunmore Press: Palmerston North.

McCulloch, G. (2011) The struggle for the history of education. Routledge: London.

Mead, H.M. (1984) Te Māori: Māori art from New Zealand collections. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art Pub: New York.

Muir, P., Wilson, T., Enoka, G., & Butterworth, E. (2022) Black ferns cultural and environmental review. Report for the New Zealand Rugby Union. Pub: Simpson – Grierson: Auckland.

Palmer, F., Erueti, B, Reweti, A, Severinsen, C & Hapeta, J. (2022). Māori (Indigenous knowledge in Sport and Wellbeing contexts: tūturu whakamaua kia tina. In D. Sturm, & R. Kerr, R. (Eds.), Sport in Aotearoa: Contested Terrain. Pub: Routledge.

Parsonson, A. Oliver, W.H., Williams, B.R. (1981). The pursuit of Mana. In W.H. Oliver and B.R. Williams (Eds.),The Oxford History of New Zealand. (pp. 140-167). Oxford: Claredon Press.

Reed, A.W. (1999) Māori myths and legendary tales. Reed Methuen, NZ.

Roser, I. (2016) Sport a tool of colonial control for the British Empire. The Butler Scholarly Journal. Retrieved from https://butlerscholarlyjournal.com/2016/04/30/sport-a-tool-of-colonial-control-for-the-british-empire/

Simon, J., & Smith, L.T. (2001). A civilising mission? The making of the native schools system 1867-1969. Auckland. Auckland University Press.

Smith, G.H. (1997). Kaupapa Māori: Theory and praxis. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Education Department. The University of Auckland.

Smith, G.H. (2015). Equity as critical praxis: The self-development of Te Whare Wananga o Awanuiarangi. In M. Peters and T. Besley’s (Eds.), Paulo Freire: The global legacy. pp (pp. 55–79). New York.

Smith, L.T. (2021) Decolonising methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (3rd Edition) Bloomsbury Books: London.

Statistics New Zealand. (2022). Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2022. Accessed: 17 November, https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/Māori-population-estimates-at-30-june-2022/

Stewart-Withers, R., & Hapeta, J. (2021) Sport as a vehicle for positive social change in Aotearoa. In D. Belgrave and G. Dodson’s (Eds.), Tū Tira Mai: Making Change for New Zealand, Massey University Press.

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15