Jamie Marshall1 and Russell Martindale1

1 The School of Applied Sciences, Edinburgh Napier University, UK

Citation:

Marshall, J. & Martindale, R. (2024). A Delphi study exploring physical and emotional safe spaces within sport for development projects targeting mental health. Journal of Sport for Development. Retrieved from https://jsfd.org/

ABSTRACT

Sport for Development (SFD) offers a promising vehicle for intervention in the battle against the global mental health crisis. Sport on its own is not enough to support positive mental health and requires additional structuring to achieve such aims. One established ‘plus’ element to SFD is the concept of safe spaces, yet there has been limited robust exploration into the key aspects of safe spaces and their implementation. This study aimed to build consensus on key aspects of safe space facilitation through the use of the Delphi method. Coaches (n = 26) from varied SFD programs around the world (n = 12) were remotely and anonymously surveyed through initial open-ended questions. This was followed by three rounds of collaborative refinement of statements to build consensus. In total consensus was reached on 75 statements relating to the characteristics of safe spaces within SFD targeting mental health. These consensus statements have pragmatic implications for the implementation of safe spaces within SFD, while providing the starting point for further research and the development of targeted evaluation tools. Crucially the findings also highlight the complexity of safe spaces, and the degree of intentional planning, preparation, and effort they require within a SFD context.

INTRODUCTION

Mental health represents a considerable challenge with recent research identifying that every year an estimated one in eight people globally experience one or more mental disorders (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020). Nearly one in three people meet the criteria for a common mental health disorder over the course of their life (Steel et al., 2014). Poor mental health appears to have been further exacerbated by the Covid 19 pandemic for both adult (Nochaiwong, 2021) and youth (Racine et al., 2021) populations. Evidence suggests a higher prevalence of negative mental health in high-income countries, however, the high levels of negative stigma that exists in low-income countries is likely leading to under reporting in this context (World Health Organization, 2022). The universal need for innovative approaches to mental health support is clear both in terms of overstretched acute mental health services in high-income countries (Oxtoby, 2022), and in low-income settings where determinants such as conflict or lack of investment have led to a broadly lacking mental health infrastructure (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

This universal need must be framed within contextual understandings of mental distress which remain poorly represented in epidemiological studies (Kohrt et al., 2014). Negative mental health has been shown to be tied to a range of contextual correlates, for example, those exposed to conflict and war, experience much higher prevalence of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Priebe et al., 2010). Similarly, a global review of adolescent suicidal ideation found an average global prevalence of 14%, rising to 21% in an African context, with gender, socioeconomic status, peer conflict, loneliness, and isolation, associated with a greater risk of suicidal ideation (Biswas et al., 2020). Homelessness and its associated challenges have been linked with significantly higher levels of suicidal ideation than the general population in a recent meta-analysis of work from mainly high income countries (18 of 20) (Ayano et al., 2019). Given the social and environmental nature of these correlates within a broad range of contexts, this study explores the wider need for targeted mental health interventions that focus on intentional utilization of protective community based factors to better support positive mental health.

One protective factor that is well established in supporting positive mental health is physical activity, even at low doses (Teychenne et al., 2020) and has been identified as a key priority for promoting mental health on a global scale (World Health Organization, 2022). This positive relationship is apparent across a range of populations and sociodemographic factors including youth (Biddle et al., 2019), the elderly (Cunningham et al., 2020), gender (Halliday et al., 2019), and education (Goodwin, 2003). Despite broad positive associations between physical activity and mental health, such robust outcomes are not mirrored consistently within literature exploring the Sport for Development (SfD) paradigm. Four systematic reviews on the topic have been undertaken in the last 10 years with three finding limited evidence for SfD’s impact on mental health (Hamilton et al., 2016; Whitley et al., 2019a; Whitley et al., 2019b). The most recent review found a small positive effect on youth mental health in relation to organized sporting activities (Boelens et al., 2022). However, due to low quality methodology used within much of the work reviewed, authors across all reviews recommend caution (Boelens et al., 2022; Hamilton et al., 2016; Whitley et al., 2019a; Whitley et al., 2019b).

All four reviews highlighted a need for better understanding around mechanisms within SfD, reaffirming an established critique that SFD practice often relies upon a ‘romanticized’ notion that sport is inherently able to heal or have a positive impact (Coalter, 2007). This is clearly expounded within a randomized controlled trial carried out in post-conflict Uganda that highlighted how a football based SFD intervention had a significant negative impact on participants’ mental health (Richards et al., 2014). The research team carried out comprehensive process evaluation that enabled them to identify that while the football component of the intervention was well developed and delivered, it was highly competitive, while the peace building elements were neglected (Richards & Foster, 2013). In combination these two features may account for the negative mental health findings. The importance of ‘plus’ elements, that is the elements integrated within SFD that target key outcomes, is a clear theme within SFD literature (Coalter, 2007). This is echoed in recent physical activity literature that stressed the importance of the quality of physical activity including activity types that promote enjoyment and autonomy, facilitator/coach manner and style, positive social environments and pleasant physical environments (Vella et al., 2023). Indeed, where these ‘plus’ elements and the quality of their delivery are clearly prioritized, individual SFD evaluations have been associated with positive outcomes in relation to mental health (Marshall et al., 2021; Sherry & May, 2013).

Understanding the ‘plus’ elements, processes, and theoretical mechanisms within SFD has been identified as a key priority for future research (Boelens et al., 2022; Hamilton et al., 2016; Whitley et al., 2019a; Whitley et al., 2019b). One element that consistently appears within SFD research and practice is the concept of a safe space, a concept that also exists in wider mental health literature (Bell et al., 2018). It should be noted that there exists no consensus on a single definition around safe spaces in relation to mental health. This is true in SFD and social science literature where it has been described as a ‘catch all’ term that remains ‘contested and underdeveloped’ (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014, p.634), and in clinical paradigms where comparable elements continue to prove difficult to define (Hartley et al., 2020). The highlighted underdevelopment of safe spaces within the literature emphasizes the clear need for robust interrogation of the concept, especially as an important ‘plus’ element within SFD targeting mental health.

The aim of this research was to explore and build consensus upon the key characteristics of safe spaces as delivered by SFD organizations in a range of different contexts. The research also sought to explore and, where possible, build consensus around the pragmatic steps to their implementation. The focus of the research was on safe spaces as an integral mediator or ‘plus’ element in SFD, but the study also explored perceived benefits to safe spaces to better understand their role with wider SFD program theory. While the aim was to build consensus, the research was carried out with awareness of the fundamentally contextual and community based nature of safe spaces and their delivery (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014).

Literature Review

In order to best investigate safe spaces within SFD, a thorough literature review on the topic was carried out. Safe spaces have been attributed a range of characteristics within SFD contexts to ensure they are inclusive, secure, welcoming, supportive, patient, and challenging of stigma (Brady, 2005; Coalter & Theeboom, 2022; Marshall et al., 2020). The most in depth and targeted exploration of safe spaces within SFD was carried out by Spaaij and Schulenkorf (2014). Like previous work, they highlighted that safe spaces are not inherent within SFD but required significant intentional planning and work. The research identified that safe spaces have physical (safety from physical harm and security), psychological/affective (protection from psychological or emotional harm), sociocultural (based on familiarity, recognition, and acceptance to feel comfortable), political (an environment based on open dialogue, collaborative learning, and respect for difference), and experimental (concerned with the risk-taking and experimentation) dimensions to them. The study identified this multidimensional description within examples from SFD in Sri Lanka, Israel, and Brazil, and provided a framework for future research. While the discussion around the concept of safe spaces has been initiated within the literature, and broad domains have been identified, there remains a lack of clear, rigorous definition of safe spaces within SFD, especially in terms of linking to the pragmatic steps required to facilitate them. Such research, grounded in real world experiences, would be especially valuable given the importance of safes spaces as a key ‘plus’ element with SFD (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014), and their alignment with global priorities around interventions targeting key protective factors for mental health (World Health Organization, 2022).

Given the limited exploration of safe spaces within SFD targeted research, it is necessary to interrogate wider paradigms and their associated literature on the topic. It is notable that discussion of safe spaces can be identified within traditional cultural practices serving a community well-being function. The traditional Zimbabwean concept of Nhanga involves women of different ages coming together to discuss shared emotional experiences in an open, trusting, and collaborative space that intentionally subvert existing power structures and dynamics (Gumbonzvanda et al., 2021). Such an approach highlights the long standing value that community safe spaces hold within non-western traditional practices and offer insight not available within western dominated mental health research. Another example of insight from within community contexts would be the identification of beauty salons in the US as a space where Black women felt comfortable to relax, let their guard down, discuss shared experiences, and seek role models around the topic of racial inequality (Battle, 2021).

Research into organized positive youth development in Canada further builds on characteristics of community based safe spaces, highlighting that they should be based on being respectful, supportive and enabling open discussion to impact positively on youth well-being (Ramey et al., 2023). These interpersonal elements to safe spaces are echoed and developed in research focused on supporting the well-being of HIV health professionals, in the face of frequent exposure to secondary trauma (Wills, 2020). To best support such workers in avoiding burnout and poor mental health the importance of vulnerability (open to sharing one’s own experiences with others), authenticity, and judgement free peer support was highlighted. Structural elements were also stressed, especially the need for regular checking in (Wills, 2020). Other structural elements such as who is facilitating safe spaces have been explored in refugee contexts. The utilization of refugee staff has been identified as foundational to providing a safe space for health care provision through such staff proving a bridge to patients, their ability to be culturally sensitive and develop deeply trusting relationships (Özvarış & Hricak, 2019). Research into UK social service day centers have further highlighted structural elements such as normalizing and non-pathologized topics, using stealth approach to health, and offering services with stability and consistency (Tucker, 2010). Research in a similar paradigm echoed this while prioritizing the need for mental health day centers to be developed collaboratively to feel like refuge for users (Bryant et al., 2011). One further structural element that, perhaps surprisingly, is not explicitly explored in a lot of research is the importance of ensuring physical safety when delivering safe spaces for mental well-being, especially for participants at risk of abuse, persecution, or stigma such as LGBTQIA+ populations (Ramey et al., 2023). Existing research into community led safe spaces offers valuable insight into the nature of safe spaces and their key characteristics. The broad range of areas touched upon further highlights the multidimensional and complicated nature of safe spaces as highlighted within SFD literature (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014).

Alongside community contexts, clinical settings offer important insight into implementation of safe spaces for mental health and well-being. In exploring alternative provision to the emergency departments for mental health patients, Andrew et al. (2023) highlighted the need for non-pathologized spaces, that are collaborative and targeted for population needs, and promote inclusivity and a sense of belonging. Alongside research into explicit clinical safe spaces, insight can be garnered from the body of research exploring the therapeutic alliance, the nature of the relationship between clinician and patient. It should be noted as in safe spaces, the difficulty in defining therapeutic alliance has been discussed at length in medical literature (Hartley et al., 2020). Research in mental health nursing has emphasized a range of key characteristics for effective therapeutic alliance that could translate into safe space provision. Such elements include empathy, being non-judgmental, collaborative decision making, consistency and availability, being focused and expert on population needs, building trust, and being authentic (Dziopa & Ahern, 2009; Hartley et al., 2020; Kirsh & Tate, 2006; Moreno-Poyato & Rodríguez-Nogueira, 2021). The multidimensional and complex nature of safe spaces implementation is once again recognized within clinical paradigms, and despite their apparent importance there is little evidence for interventions with fidelity that effectively promote or develop the concept of therapeutic alliance (Hartley et al., 2020).

This literature review into research exploring safes spaces, or comparable constructs, within SFD, community and clinical settings, has highlighted a range of potentially important elements that may contribute to the implementation of effective safe spaces. There exists no clear consensus within any paradigms on the definition of a safe space (Hartley et al., 2020; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014), and this might be in part due to the multidimensional, complicated, and highly contextual nature identified within reviewed literature. For the purposes of this study, and based on the surveyed literature, safe spaces are defined as implemented physical, psychosocial, and structural frameworks that support participants to feel physically and emotionally safe, and best engage with mental health targeted SFD. This definition is not intended for wider adoption, but to assist in determining the proposed scope of this study.

METHODS

Given building consensus on items within a specific sector or paradigm was the primary aim of the study, a classical Delphi framework was deemed the most appropriate. The Delphi technique was developed at the outset of the Cold War to predict the impact of technology on warfare (Custer et al., 1999). The development of the Delphi technique was guided by the premise that combined individual anonymous predictions were stronger than unstructured group predictions (Kaplan et al., 1950). The process is used to build consensus around a topic through the systematic surveying of a panel of experts on the topic of interest. A Delphi panel consists of a group of subject experts who can offer insight, and in this study work towards consensus of recommendations around the nature and pragmatic implementation of safe spaces within SFD contexts. The number of participants required for a Delphi panel is not set, though a minimum between 10-18 has been previously suggested (Paliwoda, 1983). The panel receives and responds to multiple rounds of questionnaires, the responses of which are analyzed, consolidated, and presented back to the panel for further feedback. This is often done through presenting back statements for participants to rate their agreement on. This process continues until a, usually predefined, consensus is reached. The first stage of any Delphi process is the recruitment of an expert panel on the topic in question.

Panel Selection

As the focus of this research is establishing consensus on safe spaces within SFD in a pragmatic sense, it was deemed important to bring together a panel with extensive experience in the facilitation of SFD in the real world. SFD coaches were deemed the most appropriate participants to fulfil this role and to maximize the pragmatic implications of the study. The initial stage of panel recruitment was focused on targeting SFD organizations with a track record of targeted mental health programming, ideally with evaluations to evidence their work. Organizations were also surveyed for indicators of safe space delivery (as described in existing literature) within their work. Examples of such indicators included structures to support physical safety in response to contextual threats, elements focused on trust building or empathy, collaborative approaches to intervention development and delivery, and evidence of dismantling of negative social power structures.

A purposive approach was used to identify and contact a range of SFD gatekeepers such as academics, umbrella organizations, and sector awards programs to elicit recommendations for organizations to invite to the study. An online search was also carried out with a specific focus on SFD targeting mental health with robust grey literature, ideally utilizing validated measures, and supporting outcomes. An initial 63 organizations were identified via preliminary searches/recommendations, and this was refined to 20 following more in-depth surveying of safe space indicators and to ensure diversity of sports modality. At this point potential bias was noted in the lead author’s exposure to multiple surfing programs in previous work. A limit to the number of surfing programs involved was set (3) to ensure diversity of sport modalities within the study. Surfing projects with the most developed safe space indicators from available evidence were approached for inclusion.

When identified for possible involvement, organizations were contacted with a brief about the project to confirm a) their availability and willingness to be involved, and b) that the organizations themselves agreed that they fit the scope of the project. Projects were given the option to include between 1-3 coaches in the study, prioritizing those with the most experience facilitating safe spaces. This allowed organizations to suggest participants based on their scale/capacity and to include, where possible, diversity of perspectives on safe spaces within the same SFD organizations. At the conclusion of this process, 12 organizations were identified and a breakdown of their characteristics, and number of coaches who volunteered to participate in the study can be viewed in Table 1, including their respective websites for more information.

Table 1 – SFD Organizations Participating in the Study

| Organization | Location | Sport Modality | No. of Coach Participants | Website |

| ClimbAID | Lebanon | Rock Climbing | 1 | https://climbaid.org/ |

| Elman Peace | Somalia | Multisport | 2 | http://elmanpeace.org/ |

| HIV Free Generation | Kenya | Surfing | 2 | https://www.hivfreegeneration.org/ |

| Lost Boyz Inc | USA | Baseball | 3 | https://www.lostboyzinc.org/ |

| Maitryana | India | Netball | 3 | https://maitrayana.in/ |

| Moving the Goalposts | Kenya | Soccer | 3 | https://www.mtgk.org/ |

| Skateistan | South Africa | Skateboarding | 2 | https://skateistan.org/ |

| School of Hard Knocks | United Kingdom | Rugby | 2 | https://www.schoolofhardknocks.org.uk/ |

| Street Soccer Scotland | United Kingdom | Soccer | 2 | https://streetsoccerscotland.org/ |

| Waves for Change | South Africa | Surfing | 2 | https://waves-for-change.org/ |

| Waves for Hope | Trinidad | Surfing & Skateboarding | 2 | https://www.waves-for-hope.org/ |

| Watford FC Community Trust | United Kingdom | Soccer | 2 | https://www.watfordfccsetrust.com/ |

A deliberately broad range of organizations were targeted for the study to offer different perspectives on safe spaces within different contexts. An example of this breadth of context can be seen in the contrast between Elman Peace and Street Soccer Scotland. More specifically, Elman Peace works in Somalia supporting young people who have experienced trauma, including children associated with armed groups. Street Soccer Scotland on the other hand support individuals in the United Kingdom facing social isolation and homelessness. The sample also included variety in terms of the types of sports projects utilized for mental health objectives which allowed for consideration of pragmatic elements of delivering safe spaces within different sporting frameworks (for example team vs individual sports). While the sample was not designed to be directly representative, the most represented sport was soccer with 35% of participating coaches being involved in interventions that utilize soccer. This aligns with soccer being previously identified as the most common sport for SFD delivery (Svensson & Woods, 2017). For the 26 coaches who took part the average age was 31.62 (SD = 9.39) and the gender breakdown 54% male and 46% female.

Procedures

The first important step within a Delphi process is to define consensus a priori (Diamond et al., 2014). For this study, a suitable consensus was defined as at least 80% of participants scoring 4 or 5 (agree/strongly agree) on a 5-point Likert Scale (Diamond et al., 2014). This Likert Scale offered multiple levels to differentiate strength of view for agreement and disagreement while also offering a neutral opinion. The length of time each round was open for was set a priori at four weeks, though extensions were allowed for based upon respondent rate, and a response rate of at least 80% was preferred prior to moving on to the next round of the Delphi. A further priority throughout the whole process was the anonymization of participants at all stages. This was deemed important not only as part of established Delphi processes, but also so participants felt they could respond freely and honestly without fear of any repercussions related to their employment. An online platform (Qualtrics) was deemed most appropriate to maintain anonymity, to minimize disruption for participants, and to accommodate the global spread of participants. In total three rounds of questionnaires were carried out before consensus was reached on all items. Response rates were high throughout the study (Round 1:100%, Round 2: 92%, Round 3: 96%). Ethical approval was granted by the Edinburgh Napier School of Applied Sciences Ethics Committee on 03/03/2022 (Reference Code: 2850475). This ethics process involved in-depth discussion of research protocols with a committee independent of the study and piloting of questions and processes. The chief ethical priority, as already highlighted, was always maintaining participant anonymity.

Round 1 Question Development

An initial round of open-ended questions was developed in line with classical Delphi procedures. These initial questions were based upon a review of current literature exploring safe spaces within SFD and wider literature. The conducted literature review highlighted that safe spaces are multidimensional in nature and identified a range of key characteristics relating to physical safety, psychosocial concepts, implementation structure, population expertise, and interpersonal power dynamics all considered. After an initial open-ended question about what participants perceived as the most important elements for safe spaces in SFD, these dimensions allowed for a systematic questioning of the broader topic. Given the breadth of the topic, all initial questions were designed to be as open ended as possible to allow space for novel insight as well as non-leading exploration of existing concepts. All questions also asked for reflections about the pragmatic elements of implementation that coaches’ expertise could illuminate. This broadly consisted of asking participants for the practical steps they would recommend to implement the concepts and ideas raised within open ended questioning.

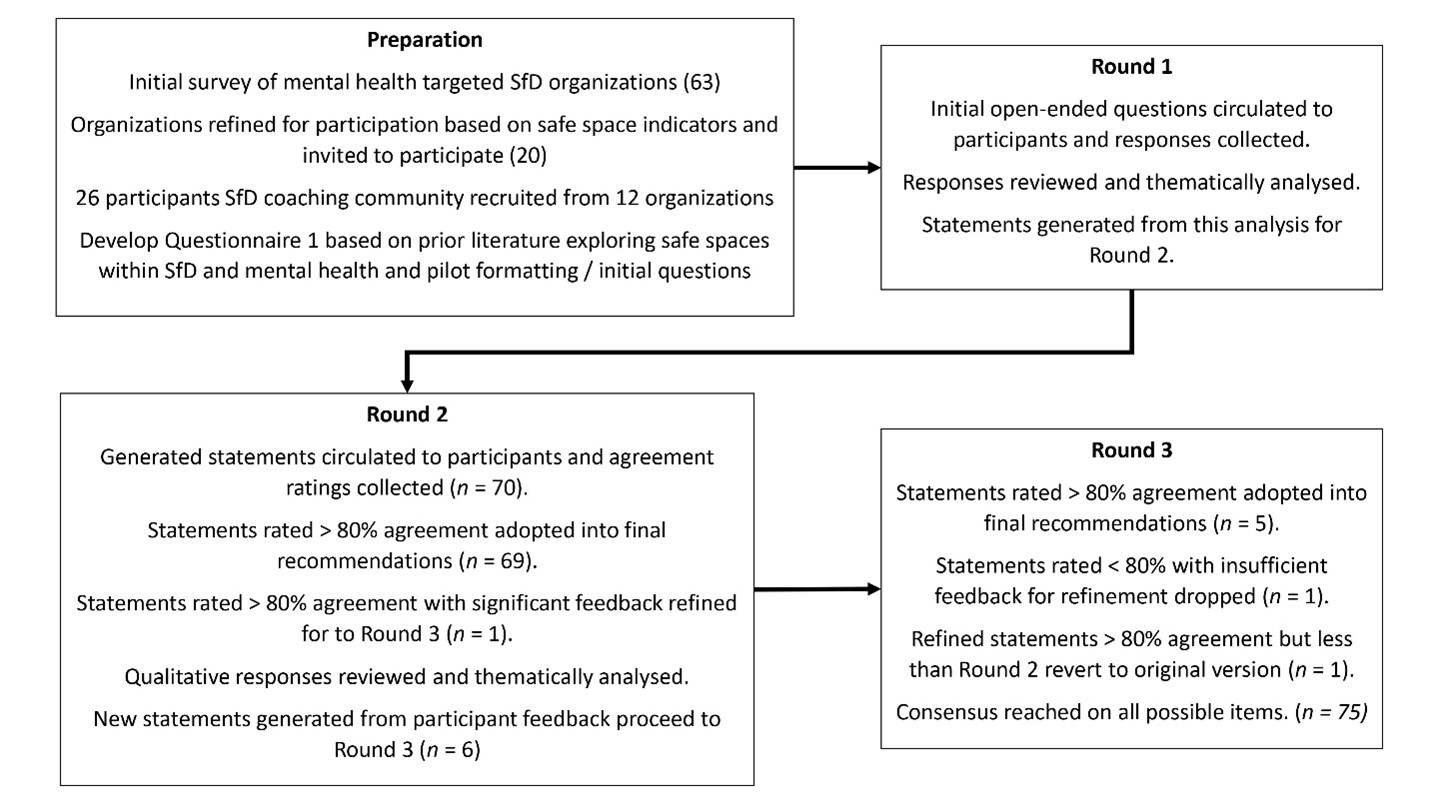

Initial analysis and statement development

Responses to open ended questions in Round 1 were initially explored through process coding, before codes were mapped, categorized, and tabulated to explore key themes from within the data (Saldaña, 2021). These themes provided the basis for initial statements presented back to participants from Round 2 to explore consensus. In subsequent rounds (2, 3), participants received feedback around responses from the previous round and were given the opportunity to offer further comment or make modifications to statements. Participants were requested to specifically offer qualitative insight on statements they disagreed with to enable statement refinement. Qualitative feedback was coded and analyzed within the same framework as Round 1 (process coding, mapping, categorization, and tabulation). This process led to new or modified statements in the subsequent round. Where significant new themes emerged within qualitative feedback, new statements were generated and included within subsequent rounds. Some qualitative feedback was deemed to offer improved wording on items that consensus had already been reached upon (agreement > 80%). Where this was the case refinements were made and presented back to the participants and if a higher agreement rating was achieved, the refinements were kept. If the agreement was less than the previous round the refinements were reversed. This is a deviation from a classical Delphi method but was deemed to allow for further refinement without compromising a priori agreement procedures. At the culmination of Round 3, consensus had been reached around all items resulting in a list of recommendations for future intervention design and implementation. Items that did not reach a prior consensus (agreement rating < 80%) and that did not have sufficient qualitative feedback to refine were dropped. The full research process has been surmised and visualized within Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Delphi on Safe Spaces in SFD Research Process

After receiving Round 1 data a slight alteration was made to processes relating to barriers to safe space implementation. The initial responses included a range of highly contextual examples that could be lost in any form of consensus building exercise. For example, items around firearms would be much less relevant in contexts where firearms are less prevalent (e.g., UK based SFD programs). The research team deemed collecting a full list of examples of barriers with contextual nuances would be more valuable than abstract consensus items. As such a list of barriers was collected from Round 1 (n = 21) and presented back in Round 2 with an explanation of the change in process and the opportunity for participants to add any further barriers they believed were missing. Participants included a further 3 barriers in Round 2.

RESULTS

Having completed 3 rounds of the Delphi, consensus was reached upon 75 statements relating to the characteristics, implementation, and benefits of safe spaces in SFD targeting mental health and can be viewed in Table 2 and 3 below. Of the 75 statements, 70 were generated in round 1 and reached a priori threshold for consensus (>80%) in round 2. Of these consensus statements 60% achieved 100% agreement from participants. A further 5 items (36, 37, 63, 74, 75 and italicized in tables for clarity) were generated based upon round 2 feedback and all subsequently reached consensus threshold in round 3. One statement (20) achieved threshold for consensus in round 2 but was refined based on significant participant feedback. When presented back to participants in round 3 the statement again achieved consensus, however it was at a lower percentage than round 2 and so the original version of the statement was retained in the study results.

Emergent consensus statements describing safe spaces and how to deliver them (statements 1-63) were labelled as either conceptual Safe Space Characteristics, or within pragmatic implementation groupings such as Structural Elements of Safe Spaces or Coach Behaviors for Safe Spaces. These groupings emerged in the initial round of analysis of open ended responses and were maintained throughout the process as they were deemed to support pragmatic aims of the study with conceptual characteristics grouped for discussion within wider literature, structural elements grouped together to aid intervention design and management, and coach behaviors grouped to support coach training and practice. These groupings were also utilized to structure a pragmatic resource to accompany this research and best inform SFD practitioners of key findings.

Table 2 – Consensus Statements on Safe Spaces in SFD: Characteristics, Structural Elements, and Coach Behaviours – (Round 2 – normal text, Round 3 – italicized)

| Statement Number | Safe Spaces in SFD Statements – (Round 2 – normal text, Round 3 – italicized) | Round 2 Agreement | Round 3 Agreement |

| Safe Space Characteristics (safe spaces should be…) | |||

| 1 | Free from judgement | 100% | NA |

| 2 | Empathetic | 100% | NA |

| 3 | Respectful | 100% | NA |

| 4 | Trusting | 100% | NA |

| 5 | Patient | 100% | NA |

| 6 | Inclusive and accepting | 96% | NA |

| 7 | Supportive | 100% | NA |

| 8 | Encouraging | 100% | NA |

| 9 | Caring | 92% | NA |

| 10 | Consistent and reliable | 92% | NA |

| 11 | Authentic and honest | 100% | NA |

| 12 | Collaborative | 100% | NA |

| 13 | Equitable (participants and facilitators held to same standards) | 100% | NA |

| Structural Elements for Safe Spaces | |||

| 14 | Projects should be aware of, and mitigate for, contextual potential reprisals against or negative repercussions for participants engaging with the project. | 100% | NA |

| 15 | The project must carry out thorough risk assessment of activities, including where possible removing hazards present in activity locations and weather planning. | 100% | NA |

| 16 | The project must be delivered in a secure location that provides a barrier, as much as is possible, to external contextual threats to the safe space. | 100% | NA |

| 17 | The project must provide activity based first aid cover. | 100% | NA |

| 18 | The project must provide appropriate and sufficiently maintained equipment. | 100% | NA |

| 19 | Projects should always manage hydration appropriately. | 92% | NA |

| 20 | Where feasible and appropriate projects would replace energy lost through activities through feeding elements. This is especially true for populations facing challenges associated with food insecurity. * | 85%* | 84%* |

| 21 | The project should provide regular training for facilitators, focused on up to date mental health and project specific practices. | 100% | NA |

| 22 | Facilitators should be appropriately qualified for their context; it must be noted the nature of these qualifications will vary around the world. | 100% | NA |

| 23 | Where possible and feasible facilitators should have access to clinical/professional support for their own mental health. | 100% | NA |

| 24 | Projects should maintain contextually/project appropriate rules for participants. | 100% | NA |

| 25 | Where appropriate, possible and feasible facilitators should signpost participants to further clinical/professional support for their mental health. | 100% | NA |

| 26 | The project must have contextually developed and targeted child protection policies. | 100% | NA |

| 27 | Where feasible and appropriate, facilitators should be recruited from within the community and/or the population served by the project. | 88% | NA |

| 28 | The project must be grounded in expert knowledge of the target population. | 92% | NA |

| 29 | The project must have appropriate feedback mechanisms and be open to feedback provided. | 100% | NA |

| 30 | Projects should, as much as is possible, provide access to coaches of appropriate genders for participants. | 100% | NA |

| 31 | Projects should, as much as is possible, provide gender appropriate changing/toilet facilities. Where impossible structures to mitigate for this, such as staggered changing, individual changing etc, should be put in place. | 100% | NA |

| 32 | The project must be up front and transparent around its goals and intentions. | 100% | NA |

| 33 | Safe spaces are a collaborative process, where possible, participants should be engaged in setting project structures around safe spaces (for example collaborative approaches to rule/goal setting). | 100% | NA |

| 34 | The project must remain aware of changing circumstances in local context or community that could impact on its delivery. | 96% | NA |

| 35 | Projects should be aligned on purpose and implementation of activities, there should not be dissonance between management and facilitators. | 96% | NA |

| 36 | Programs should plan to appropriately manage pre-existing social relationships between coaches and participants within the community. | NA | 92% |

| 37 | Programs should structure activities to encourage participants to take part at their own pace, and plan for participants taking part at different paces. | NA | 96% |

| Coach Behaviours for Safe Spaces | |||

| 38 | Coaches should maintain appropriate physical boundaries. | 100% | NA |

| 39 | Coaches should appropriately manage competitive elements of activities to ensure they do not undermine safe space provision. | 96% | NA |

| 40 | Coaches should be patient with participants, understanding where they have come from and offering no judgement. | 96% | NA |

| 41 | Coaches should never over promise on things that they cannot deliver. | 100% | NA |

| 42 | Coaches must be intentional in their use of language and share this with participants. | 100% | NA |

| 43 | Coaches must be aware of, and able to implement all child protection policies. | 100% | NA |

| 44 | Coaches should always be aware of their own tone and body language when facilitating. | 100% | NA |

| 45 | Coaches should offer an appropriate degree of vulnerability to build trust with participants, such as sharing examples from their own lives. | 96% | NA |

| 46 | Coaches must never show favouritism. | 100% | NA |

| 47 | Coaches should endeavour to include all participants within all activities, as much as is possible. | 96% | NA |

| 48 | Coaches should utilise real world examples within discussions of mental health. | 96% | NA |

| 49 | Coaches must not tolerate bullying or harassment of any kind. | 100% | NA |

| 50 | Coaches should actively and intentionally listen to participants within group discussion/activities. | 100% | NA |

| 51 | Coaches should role model behaviours relating to safe spaces and project aims. | 100% | NA |

| 52 | Coaches should plan for potential difficult conversations and/or topics that may come up. | 100% | NA |

| 53 | Coaches must always be aware of and remove wherever possible, perceived and actual contextual barriers to participation. | 100% | NA |

| 54 | Coaches must be experts in the population targeted. | 92% | NA |

| 55 | Coaches should appropriately challenge negative stereotypes/judgements that arise within activities. | 100% | NA |

| 56 | Coaches should especially challenge gender stereotypes around sport participation. Where possible the local community should also be engaged with this discussion. | 100% | NA |

| 57 | Coaches should be held to the same standards of behaviour as participants. | 100% | NA |

| 58 | Coaches should always facilitate with an awareness of wider context and what is going on in the community. | 100% | NA |

| 59 | Coaches must be aware of biases and/or stigma they may hold, and that may be prevalent within the local context. | 100% | NA |

| 60 | Coaches should intentionally provide time/space for reflection on activities/learnings. | 100% | NA |

| 61 | Coaches should allow for mistakes and, wherever possible, reframe examples of failure as learning opportunities. | 100% | NA |

| 62 | Coaches must be open to questions that emerge from activities. | 100% | NA |

| 63 | Coaches should encourage and support participants to take part at their own pace. | NA | 96% |

The study also explored consensus statements on coach perceptions of the benefits of safe spaces within a SFD context and are displayed in Table 3 (statements 63-75). While impact is ideally explored from a participant perspective, consensus statements generated by coaches still hold significant value given coaches exist as experts delivering safe spaces in SFD in real world situations. These perceived benefits include factors such as respite, mental health nurturing, developing coping skills, relationship building, provision of learning and challenge opportunities, and community benefits.

Table 3 – Consensus Statements on Perceived Safe Space Benefits in SFD – (Round 2 – normal text, Round 3 – italicized)

| Statement Number | Statements – (Round 1 – normal text, Round 2 – italicized) | Round 2 Agreement | Round 3 Agreement |

| 64 | Safe spaces are sanctuaries that provide participants with respite from wider challenges face away from projects. | 96% | NA |

| 65 | Safe spaces allow participants to enjoy activities away from pervading stigma and/or stereotypes. | 100% | NA |

| 66 | Safe spaces can in and of themselves nurture mental health. | 100% | NA |

| 67 | Safe spaces allow participants to get advice about mental health free from judgment/stigma. | 100% | NA |

| 68 | Safe spaces are ideal for learning about and developing coping/resilience mental health skills. | 100% | NA |

| 69 | Safe spaces provide an opportunity for developing new and positive relationships. | 100% | NA |

| 70 | Safe spaces allow participants to share how they are feeling openly, something they may not otherwise have access to on a regular basis. | 100% | NA |

| 71 | Safe spaces allow participants to be themselves. | 100% | NA |

| 72 | Safe spaces optimise learning experiences and activities. | 100% | NA |

| 73 | Safe spaces can promote the inclusion of similar behaviours/spaces within the local context/community away from the project. | 96% | NA |

| 74 | Safe spaces allow youth participants a space to be children and play, in contrast to adultification (premature exposure to adult stressors and responsibilities) they may face in wider lives. | NA | 96% |

| 75 | Safe spaces allow participants to challenge themselves and take on new responsibilities. | NA | 92% |

As described previously, the process exploring barriers was adapted to be more inclusive of contextual nuance of the different SFD organizations participating. A full list of the barriers that participants described in implementing safe spaces for SFD is presented below in Table 4 with items in italics generated in Round 2. These included factors related to environmental and personal safety, equipment, nutrition, weather, inclusive spaces and facilities, negative community influences or challenges, and coach behaviors.

Table 4 – Barriers to Implementing Safe Spaces in SFD – (Round 1 – normal text, Round 2 – italicized)

| Barriers to Implementing Safe Spaces in SFD (Round 1 – normal text, Round 2 – italicized) |

| Rubbish/trash at the activity site |

| Dangerous objects in and around activity site (e.g. munitions, firearms, landmines, broken glass, drug paraphernalia, other sharp items) |

| Inappropriate equipment |

| Poorly maintained equipment |

| Lack of nutritional support |

| Poor/dangerous weather conditions |

| Lack of private and gender appropriate spaces (especially for changing) |

| Lack of suitable toilet facilities |

| Inappropriate behaviours of non-programme individuals in proximity of activity site (e.g. drinking, drug taking, immodesty) |

| Intrusion of non-programme individuals (e.g. heckling, shouting, trying to join in, using equipment) |

| Interference of negative community groups (e.g. armed groups, criminal groups, gangs) |

| Participants not being allowed to attend by third parties (e.g. family, peers, teachers, gangs, probation personnel) |

| Poorly managed participant behaviour |

| Harmful traditional beliefs within the community |

| Negative stereotypes within the community |

| Reluctance to allow female participation |

| Community hostility and/or suspicion of programme |

| Reprisals against participants for involvement |

| Tensions between different local communities |

| Political/religious/tribal divisions |

| Lack of local child protection knowledge and infrastructure |

| Inappropriate behaviour of coaches (not being positive role models by e.g. not taking care of equipment, not being motivated, not being prepared etc.). |

| Working alongside difficult to access and/or isolated communities |

| The implications of trauma upon participants |

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This Delphi study aimed to build consensus on key characteristics, components, and perceived benefits of safe spaces from across a wide range of SFD projects targeting mental health. One of the priorities of this study was to identify if there were universal concepts, and pragmatic steps present within the delivery of safe spaces in SFD from across a broad range of contexts. The large number of consensus statements achieved, and the high agreement ratings that were present across all results suggests shared elements exist within safe space facilitation despite the lack to consensus apparent within existing literature both SFD focused (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014) and comparable clinical paradigms (Hartley et al., 2020). The robust consensus on characteristics of safe spaces within SFD (items 1-13) could provide the foundation for better definition of the term in a manner that has so far proved elusive. Further research, especially considering participant perspectives, could help to realize this goal.

The multidimensional nature of statements generated in this research highlights the complexity of implementing safe spaces and is mirrored in wider literature across multiple paradigms (Andrew et al., 2023; Gumbonzvanda et al 2021; Özvarış & Hricak, 2019; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014; Vella et al., 2023). This complexity highlights how plus elements should not be ignored or taken lightly by SFD practitioners, and further challenges prevalent romanticized notions of sport as inherently good (Coalter, 2007). This complexity is further highlighted by the fact that many consensus statements taken in isolation do not offer insight into the nature of safe spaces. For example, statement 10 focuses on consistency and reliability, an element that was highlighted in the review of existing clinical literature (Dziopa & Ahern, 2009; Kirsh & Tate, 2006). While this statement appeared regularly within initial coach responses and achieved a 92% agreement rating, consistency on its own is not sufficient in the development of a safe space. Consistency supports and is related to other identified safe space elements such as consistency of positive coach behaviors such as patience and role modelling (statements 5, 40, 51), or structural considerations such as programmatic transparency (statement 32). It is important that the concept of safe spaces within SFD is not oversimplified down to individual components which could in turn potentially damage or inhibit subsequent implementation.

Such oversimplification has previously been identified as a key risk within SFD especially in terms of insufficient training, mentoring and ongoing support for SFD practitioners (Coalter, 2010), and highlights the need for monitoring and process evaluations around theoretical components of safe spaces in SFD. The nature of the Delphi process did not allow for in-depth exploration of directionality in how different consensus statements related to each other but further contributes to the ongoing process of developing program theory around safe space implementation (Vogel, 2012). Despite this complexity and the need to view findings in their totality, this study offers clear and pragmatic insight into steps organizations and coaches can take to optimize the implementation of safes spaces within SFD. The study findings are also surmised within a freely accessible pragmatic resource that will hopefully prove of use to SFD organizations (https://napier-repository.worktribe.com/output/3708533). The pack has already been shared with organizations that contributed to the study and pragmatic uses have already been reported such as use of the barriers to safe spaces section to develop a pragmatic checklist for intervention site monitoring, and use of the coach behaviors section within coach training optimization.

The concept of empathy and trust building was identified prior to this study as a key element within safe space implementation across a range of paradigms (Dzipa & Ahern, 2009; Özvarış & Hricak, 2019; Moreno-Poyato & Rodirigez-Noguieria, 2020; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014). These concepts were confirmed as important characteristics within coach consensus on safe space characteristics (statements 2 and 4). Furthermore, several potentially related statements outlined clear steps to achieve these characteristics that mirrored examples from existing research. The use of real world examples when discussing mental health (statement 48) and the importance of active listening (statement 50), represent practices identified as foundational in community mental health nursing research (Kirsh & Tate, 2006). Statement 45 describes how coaches should utilize an appropriate level of vulnerability, such as sharing examples from their own lives, to build trust with participants with a high level of consensus amongst coaches (96%). This element of trust building is especially interesting as while it is highlighted as important within recent research into surfing based SFD (Marshall et al., 2023), clinician peer support (Wills, 2020) and Australian emergency mental health provision (Andrew et al., 2023). The topic of facilitator vulnerability remains controversial and requires further robust exploration (Oates et al., 2017). Concerns about appropriateness and duty of care to practitioners (community and clinical) are valid but the strong consensus established by SFD coaches across a broad range of contexts seems to suggest it is a highly valued tool within safe space implementation.

The notion of shared experiences and population/contextual expertise enabling trust building was frequently reported in wider literature around safe spaces including SFD literature (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014), community-based settings (Battle 2021; Gumbonzvanda et al., 2021; Özvarış & Hricak, 2019), and clinical paradigms (Andrew et al., 2023; Kirsh & Tate, 2006). This approach was reflected in several consensus statements on the topic, such as the project and the coaches needing to be grounded in expertise about the target population (statements 28 & 54). One of the most obvious structural manifestations of this point was statement 27: “Where feasible and appropriate, facilitators should be recruited from within the community and/or the population served by the project.” Multiple SFD organizations who took part in this study had clear pathways and examples of former participants going on to become coaches/facilitators. This was also highlighted as an extremely valuable structure to incorporate where possible in comparable literature such as Özvarış and Hricak’s (2019) research into the use of refugees as healthcare staff within a refugee focused project. There may be situations where this approach is not directly possible due to limited access to members of the target population with the appropriate skills, or no capability to offer the required training. Given the consensus around this item and its triangulation with wider research, prioritizing the development and hiring of coaches from within target populations seems a worthwhile long-term goal to optimize the facilitation of safe space provision within SFD.

Consensus statements within this study also align with wider discussions around the continued deinstitutionalization of mental health, and recognition of the community as a positive location for mental health work as part of a more broad, coherent system (Andrew et al., 2023; Bryant et al., 2011; Tucker, 2010). Locating mental health work in the community can also avoid pervading stigma for participants around accessing mental health or social support in what has previously been described as a ‘stealth’ approach within SFD (Marshall et al., 2023) and in clinical settings (Andrew et al., 2023). It is important to stress that there continues to be an important role for clinical approaches and deinstitutionalization is not about replacing them, but about improving access and supporting/supplementing them through effective integration with community assets (Andrew et al., 2023; Erulkar & Medhin, 2017; Tucker, 2010). Participating coaches’ agreement with this concept is demonstrated by the 100% consensus on the importance of effective signposting in statement 25. The community as a location for mental health does however bring its own challenges including a range of negative biases, stigma, and discrimination. These negative community elements, which are well represented in barriers to safe spaces discussed by coaches, need to be managed appropriately within effective safe space implementation. Interventions maintaining awareness of changing circumstances in local context or community that could impact on its delivery (statement 34) or coaches reflecting on biases and/or stigma they may hold, and that may be prevalent within the local context (statement 59) provide example strategies for this.

One theme that clearly emerged across a range of consensus statements was the collaborative nature of developing safe spaces for intervention participants. Indeed, being collaborative was identified as a key characteristic of safe spaces (statement 12) and an important consideration for intervention structuring (statement 33), with both of these statements achieving 100% consensus amongst participants. Similar importance was placed on equitable relationships between coaches and participants (statements 13 and 57).

One of the participating organizations, Waves for Change offered a clear example of such a collaborative approach in grounding exercises that set the culture for their sessions. At initial sessions coaches explore together with participants how they want to feel at programs, followed by collaboratively aligning participants on behaviors and rules to support this (Waves for Change, 2022, p.16-17). This process allows for the setting of meaningful and intentional structure around safe spaces within sessions, that mirrors the prioritizing of collaboration in wider research within community (Bryant et al., 2011; Gumbonzvanda et al 2021) and within clinical settings (Andrew et al., 2023; Dzipa & Ahern, 2009; Moreno-Poyato & Rodirigez-Noguieria, 2020). Another benefit of such collaborative approaches are they address negative participant/practitioner or other negative social power dynamics in a manner that has been identified as important within wider mental health research (Andrew et al., 2023; Gumbonzvanda et al., 2021; Özvarış & Hricak, 2019). The organic development of the traditional Nhanga practice as a space that intentionally separates itself from and subverts existing power dynamics to support young Zimbabwean women’s well-being highlights the long understood value of such an approach (Gumbonzvanda et al., 2021). The kind of collaborative approaches highlighted in this research appear to be integral in enhancing safe space implementation, and mitigating negative elements related to contextual power dynamics.

When the approaches explored in this study are delivered effectively, safe spaces can become a ‘refuge’ from negative elements that are prevalent in participants’ wider lives (Battle, 2021; Bryant et al., 2011; Jost & Janicka, 2020). The importance of such a refuge, the like of which may not be easily accessible in participants’ wider lives, may account for coach perceptions around the benefits safe spaces offer on their own. Examples of this would include coaches describing safe spaces as sanctuaries providing respite (statement 64), a place where participants can avoid stigma/stereotyping (statement 65), and where young participants can be children countering contextually induced adultification (statement 74). It is notable that coach perceptions of these benefits are associated with the facilitation of safe spaces, prior to other SFD plus elements such as psychoeducation and socialization. This may be especially true within contexts where stressors are prevalent and formalized mental health support is lacking, severely damaged, and/or absent. The importance of safe spaces within refugee response settings has been previously highlighted (Özvarış & Hricak, 2019) and SFD has been identified as a cost-effective approach to development and peace (Beutler, 2008). Effective safe spaces of the kind discussed in this research, could prove a valuable, immediate, and rapidly deployable response to challenging contexts where the development of more complex mental health infrastructure is impossible or still at its initial stage.

As already highlighted, when important ‘plus’ elements, such as safe spaces, are not appropriately implemented SFD can be ineffective and even harmful to mental health outcomes (Richards et al., 2014). To better protect from such outcomes, process evaluation can offer pragmatic insight into whether ‘plus’ elements are being implemented effectively within SFD, alongside offering understanding around intervention feasibility, scaling, optimization, and bolstering impact claims (Moore et al., 2015). Development of a pragmatic tool to assess safe space implementation could be useful within the SFD paradigm, enabling earlier and better understanding of whether this key ‘plus’ element is being delivered. Such a tool would also enable an evaluation of the association between safe space implementation and outcome strength. This would be of especial use for new pilots or existing SFD models/frameworks being trialed within new contexts and may have considerations for a range of areas outside SFD. For example, clinical literature has highlighted the lack of robust measurement around the effectiveness of interventions aimed at boosting therapeutic alliance within mental healthcare (Hartley et al., 2020). The identification of key components and attributes of safe spaces in SFD within this Delphi study provides a valuable starting point for initial item development for such a tool with consensus statements providing a starting place for item development. The development of such a ‘Safe Spaces in SFD Scale’ would be a valuable and pragmatic addition to the SFD paradigm, subject to a robust process of trialing and validation.

Limitations

The Delphi method has been established as a useful method in the development of best practice guidelines, including for mental health related paradigms (Bisson et al., 2020; McMaster et al., 2020) which made it an ideal method for the aims of this study. One limitation of the Delphi as run in this study is that it did not allow for robust exploration of directionality or relationships between the different elements of safe spaces that were identified. Given the multidimensionality and complexity of safe space implementation that is well established within this paper and wider research (Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014), the lack of prioritization of the different concepts presents a challenge to new SFD organizations, especially those with limited funding. Further research to map directionality and understand priorities within safe space frameworks to address these limitations should be a priority.

Given the aims of this study, SFD coaches were identified as best positioned to fulfil the role of an expert panel for this Delphi approach on safe space implementation. One limitation of this study is that it does not consider the perspectives of SFD participants, although multiple findings do align with research exploring SFD participant experiences (Erulkar & Medhin, 2017; Marshall et al., 2020; Spaaij & Schulenkorf, 2014). To further bolster the findings of this study in terms of their pragmatic use for SFD practitioners, confirmatory research utilizing SFD participant perspectives would be beneficial. This could also form a valuable component within the item development and validation process for a safe space scale as has been suggested.

Conclusion

Overall, this Delphi study allowed for an in-depth exploration of the key characteristics, components, barriers, and benefits of safe space implementation within SFD. The findings highlight the importance of safe spaces as a ‘plus’ element in SFD targeting mental health, along with their complexity and the amount of intentional work that is required for successful implementation. The consensus statements generated offer pragmatic guidance for use in the field, along with jumping off points for future research or the development of a safe space measurement tool. Continued interrogation of safe spaces as a foundational mediator for both SFD and other community based mental health remains a priority.

FUNDING

This research was conducted with funding support from the Swedish Postcode Lottery.

REFERENCES

Andrew, L., Karthigesu, S., Coall, D., Sim, M., Dare, J., & Boxall, K. (2023). What makes a space safe? Consumers’ perspectives on a mental health safe space. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13174

Ayano, G., Tsegay, L., Abraha, M., & Yohannes, K. (2019). Suicidal ideation and attempt among homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 90, 829-842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09667-8

Battle, N. T. (2021). Black girls and the beauty salon: Fostering a safe space for collective self-care. Gender & Society, 35(4), 557-566. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211027258

Bell, S., Foley, R., Houghton, F., Maddrell, A., & Williams, A. (2018). From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine, 196, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.035

Beutler, I. (2008). Sport serving development and peace: Achieving the goals of the United Nations through sport. Sport in Society, 11(4), 359-369. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430802019227

Biddle, S. J., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G., & Vergeer, I. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 146-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011

Bisson, J. I., Tavakoly, B., Witteveen, A. B., Ajdukovic, D., Jehel, L., Johansen, V. J., Nordanger, D., Garcia, F.O., Punamaki, R.L., Schnyder, U., Sezgin, A.U., Wittmann, L., & Olff, M. (2010). TENTS guidelines: development of post-disaster psychosocial care guidelines through a Delphi process. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(1), 69-74. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066266

Biswas, T., Scott, J. G., Munir, K., Renzaho, A. M., Rawal, L. B., Baxter, J., & Mamun, A. A. (2020). Global variation in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety and their correlates among adolescents: a population based study of 82 countries. eClinicalMedicine, 24, 100395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100395

Boelens, M., Smit, M. S., Raat, H., Bramer, W. M., & Jansen, W. (2022). Impact of organized activities on mental health in children and adolescents: An umbrella review. Preventive Medicine Reports, 25, 101687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101687

Brady, M. (2005). Creating safe spaces and building social assets for young women in the developing world: A new role for sports. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 33(1/2), 35-49.

Bryant, W., Tibbs, A. and Clark, J., 2011. Visualising a safe space: the perspective of people using mental health day services. Disability & Society, 26(5), pp.611-628. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.589194

Coalter, F. (2007). A Wider Social Role for Sport: Who’s Keeping the Score? Routledge.

Coalter, F. (2010). Sport-for-development: going beyond the boundary?. In Sport in Society, 13(9), 1374-1391. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2010.510675

Coalter, F., & Theeboom, M. (2022). Literature review: Analysis of academic and practice oriented publications on youth work approaches of experiential learning practices aimed at employability (soft) skill development with young NEETs. Brussel: Vrije Universiteit Brussel – Research group Sport & Society. https://napor.net/sajt/images/EU_Projekti/CoachPLUS/Review_COACH_101120229668.pdf

Cunningham, C., O’Sullivan, R., Caserotti, P., & Tully, M. A. (2020). Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta‐analyses. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(5), 816-827. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13616

Custer, R.L., Scarcella, J.A. and Stewart, B.R., 1999. The modified Delphi technique-A rotational modification. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 15(2), pp.50-58 https://doi.org/10.21061/jcte.v15i2.702

Diamond, I.R., Grant, R.C., Feldman, B.M., Pencharz, P.B., Ling, S.C., Moore, A.M. and Wales, P.W., 2014. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(4), pp.401-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002

Dziopa, F., & Ahern, K. J. (2009). What makes a quality therapeutic relationship in psychiatric/mental health nursing: A review of the research literature. Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice, 10(1), 7-7.

Erulkar, A., & Medhin, G. (2017). Evaluation of a safe spaces program for girls in Ethiopia. Girlhood Studies, 10(1), 107-125.

Goodwin, R. D. (2003). Association between physical activity and mental disorders among adults in the United States. Preventive Medicine, 36(6), 698-703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00042-2

Gumbonzvanda, N., Gumbonzvanda, F., & Burgess, R. (2021). Decolonising the ‘safe space’ as an African innovation: the Nhanga as quiet activism to improve women’s health and wellbeing. Critical Public Health, 31(2), 169-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2020.1866169

Halliday, A. J., Kern, M. L., & Turnbull, D. A. (2019). Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 8-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.02.003

Hamilton, A., Foster, C., & Richards, J. (2016). A systematic review of the mental health impacts of sport and physical activity programs for adolescents in post-conflict settings. Journal of Sport for Development, 4(6), 44-59. https://jsfd.org/2016/08/01/a-systematic-review-of-the-mental-health-impacts-of-sport-and-physical-activity-programmes-for-adolescents-in-post-conflict-settings/

Hartley, S., Raphael, J., Lovell, K., & Berry, K. (2020). Effective nurse–patient relationships in mental health care: A systematic review of interventions to improve the therapeutic alliance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 102, 103490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103490

Ibrahim, M., Rizwan, H., Afzal, M., & Malik, M. R. (2022). Mental health crisis in Somalia: a review and a way forward. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00525-y

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2020). Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

Kaplan, A., Skogstad, A.L. and Girshick, M.A. (1950). The prediction of social and technological events. Public Opinion Quarterly, 14(1), pp.93-110. https://doi.org/10.1086/266153

Kirsh, B., & Tate, E. (2006). Developing a comprehensive understanding of the working alliance in community mental health. Qualitative Health Research, 16(8), 1054-1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306292100

Kohrt, B. A., Rasmussen, A., Kaiser, B. N., Haroz, E. E., Maharjan, S. M., Mutamba, B. B., de Jong, J.T.V.M. & Hinton, D. E. (2014). Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 365-406. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt227

Jost, A.M., Janicka, A. (2020). Patient-Centered Care: Providing Safe Spaces in Behavioral Health Settings. In M. Forcier, G. Van Schalkwyk, J. Turban, (Eds.), Pediatric Gender Identity (pp. 101-109). Springer.

Marshall, J., Ferrier, B., Ward, P., & Martindale, R. (2020). “I feel happy when I surf because it takes stress from my mind”: An Initial Exploration of Program Theory within Waves for Change Surf Therapy in Post-Conflict Liberia. Journal of Sport for Development, 9(1). https://jsfd.org/2020/11/01/i-feel-happy-when-i-surf-because-it-takes-stress-from-my-mind-an-initial-exploration-of-program-theory-within-waves-for-change-surf-therapy-in-post-conflict-liberia/

Marshall, J., Kamuskay, S., Samai, M. M., Marah, I., Tonkara, F., Conteh, J., Keita, S., Jalloh, O., Missalie, M., Bangura, M., Meesh-Leone, O., Leone, M., Ferrier, B. & Martindale, R. (2021). A mixed methods exploration of surf therapy piloted for youth well-being in post-conflict Sierra Leone. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6267. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126267

Marshall, J., Ferrier, B., Martindale, R., & Ward, P. B. (2023). A grounded theory exploration of program theory within waves of wellness surf therapy intervention. Psychology & Health, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2214590

McMaster, C. M., Wade, T., Franklin, J., & Hart, S. (2020). Development of consensus‐based guidelines for outpatient dietetic treatment of eating disorders: a delphi study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1480-1495. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23330

Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D. and Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 350. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

Moreno‐Poyato, A. R., Rodríguez‐Nogueira, Ó., On behalf of MiRTCIME. CAT Working Group. (2021). The association between empathy and the nurse–patient therapeutic relationship in mental health units: a cross‐sectional study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(3), 335-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12675

Nochaiwong, S., Ruengorn, C., Thavorn, K., Hutton, B., Awiphan, R., Phosuya, C., Ruanta, Y., Wongpakaran, N & Wongpakaran, T. (2021). Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8

Oates, J., Drey, N., & Jones, J. P. G. (2017). ‘Your experiences were your tools’. How personal experience of mental health problems informs mental health nursing practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(7), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12376

Özvarış, Ş. B., & Hricak, H. (2019). Safe spaces for women in challenging environments. The Lancet Global Health, 7(8), e1004-e1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30263-3

Oxtoby, K. (2022). Revitalising mental healthcare after covid-19. BMJ, 379. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o2122

Paliwoda, S.J. (1983). Predicting the future using Delphi. Management Decision, 21(1), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb001309

Priebe, S., Bogic, M., Ajdukovic, D., Franciskovic, T., Galeazzi, G. M., Kucukalic, A., … & Schützwohl, M. (2010). Mental disorders following war in the Balkans: a study in 5 countries. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(5), 518-528. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.37

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142-1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Ramey, H. L., Lawford, H. L., Berardini, Y., Mahdy, S. S., Khanna, N., Ross, M. D., & von Hugo, T. K. (2023). Safer spaces in youth development programs and health in Canadian youth. Health Promotion International, 38(6), https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daad166

Richards, J., & Foster, C. (2013). Sport-for-development program objectives and delivery: A mismatch in Gulu, Northern Uganda. In N. Schulenkorf & D. Adair (Eds.), Global Sport-for-Development: Critical Perspectives (pp. 155-172). Springer.

Richards, J., Foster, C., Townsend, N., & Bauman, A. (2014). Physical fitness and mental health impact of a sport-for-development intervention in a post-conflict setting: randomized controlled trial nested within an observational study of adolescents in Gulu, Uganda. BMC Public Health, 14, 1-13.

Saldaña, J., 2021. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage.

Sherry, E., & O’May, F. (2013). Exploring the impact of sport participation in the Homeless World Cup on individuals with substance abuse or mental health disorders. Journal of Sport for Development, 1(2). https://jsfd.org/2013/10/01/exploring-the-impact-of-sport-participation-in-the-homeless-world-cup-on-individuals-with-substance-abuse-or-mental-health-disorders/

Spaaij, R., & Schulenkorf, N. (2014). Cultivating safe space: Lessons for sport-for-development projects and events. Journal of Sport Management, 28(6), 633-645. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0304

Steel, Z., Marnane, C., Iranpour, C., Chey, T., Jackson, J. W., Patel, V., & Silove, D. (2014). The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 476-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038

Svensson, P. G., & Woods, H. (2017). A systematic overview of sport for development and peace organizations. Journal of Sport for Development, 5(9), 36-48. https://jsfd.org/2017/09/20/a-systematic-overview-of-sport-for-development-and-peace-organisations/

Teychenne, M., White, R. L., Richards, J., Schuch, F. B., Rosenbaum, S., & Bennie, J. A. (2020). Do we need physical activity guidelines for mental health: What does the evidence tell us?. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 18, 100315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.100315

Tucker, I. (2010). Mental health service user territories: Enacting ‘safe spaces’ in the community. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 14(4), 434-448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459309357485

Vella, S. A., Aidman, E., Teychenne, M., Smith, J. J., Swann, C., Rosenbaum, S., White, R., & Lubans, D. R. (2023). Optimising the effects of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing: A joint consensus statement from Sports Medicine Australia and the Australian Psychological Society. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 26(2), 132-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2023.01.001

Vogel, I. (2012, August 22). Review of the use of “Theory of Change” in International Development. UK Department of International Development. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a5ded915d3cfd00071a/DFID_ToC_Review_VogelV7.pdf

Waves for Change (2022). Five Pillar Curriculum Guide. Waves for Change. Retrieved January, 10, 2024, from https://waves-for-change.org/partnerships/

Whitley, M. A., Massey, W. V., Camiré, M., Boutet, M., & Borbee, A. (2019a). Sport-based youth development interventions in the United States: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1-20.

Whitley, M.A., Massey, W.V., Camiré, M., Blom, L.C., Chawansky, M., Forde, S., Boutet, M., Borbee, A. & Darnell, S.C., (2019b). A systematic review of sport for development interventions across six global cities. Sport Management Review, 22(2), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.013

Wills, M. (2020). The burn of burnout: a personal narrative of fnding a safe space to care. HIV Nursing, 20(3), 73-76.

World Health Organization. (2022, June 16). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338